An Interview with Katrina Fellerman of the Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) Evolutionarily Distinct & Globally Endangered Program. Mongabay.com’s second in a new series of interviews with ‘Young Scientists’.

|

|

For an evolutionary biologist there is no conservation group whose work is more exciting than EDGE, a program developed by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Unique in the conservation world, EDGE chooses the species to focus on based on a combination of their threat of extinction and evolutionary distinctness. Katrina Fellerman, an evolutionary biologist herself and the EDGE birds’ coordinator, describes the organization as one that focuses on species, which “to put it bluntly, if lost, there would be nothing like them left in the world today”.

Explaining further Fellerman says “We use evolutionary distinctiveness (ED) as a species-specific measure of the relative evolutionary value of species – it is a way of apportioning conservation value according to a species’ phylogenetic position. Species with few or no close relatives on the ‘tree of life’ have the highest ED scores.”

Katrina Fellerman meets a lizard in the field. Photo by Katrina Fellerman. |

The conservation group has released lists of the top 100 EDGE mammals and the top 100 EDGE amphibians, and is currently supporting conservation projects for ten “Focal Species” selected from each of these groups. Fellerman, however, is hard at work on the team’s next initiative: expanding the program to include the world’s most evolutionary distinct and threatened bird species.

While Fellerman must remain mum about much of the list—until the EDGE program releases it—she gave Mongabay.com a few likely species to tide us over while we wait: “without spoiling all the surprises, I’d have to say that the Asian crested ibis and its curious tar-like secretions, the nocturnal kakapo and its incredible faculty for weight-gain, and the maleo and its cunning use of geothermal energy for incubation purposes, stand out for me!”

Fellerman and the EDGE team use a wide range of resources to research EDGE species. “In addition to hogging as many of ZSL’s books and journals as possible,” Fellerman says, “I make extensive use of reputable web-based resources, most notably Birdlife International’s species factsheets. They have also been kind enough to allow me to make use of their library facilities. For little known species, I try to establish whether there are any researchers actively studying them that could be contacted for further information.”

Approximately only 250 adults of the endangered Asian crested ibis survive in the wild. Photo by Bjorn Anderson. |

There are around 10,000 bird species in the world today, and Fellerman notes that “a staggering one in eight of all bird species is threatened with global extinction”. The causes are those shared by all taxonomic groups, she adds. “As human populations continue to expand, the need for greater resources has intensified pressure on global ecosystems. Loss and degradation of habitat…is, unfortunately, a common threat. Overexploitation by man for both food and the pet trade has also played its part, while invasive alien species have had devastating consequences for many small island birds. Add to this the impact of climate change and disease, and it’s fair to say that birds…have had a pretty tough time of it.”

In her interview, Fellerman emphasises that the success of EDGE is dependent on public support. “The public have been invaluable in helping us raise awareness of the programme. Through their visits to our website, contributions to our knowledge base, involvement with online discussions and encouragement of others to do so, they have been incredibly supportive.” As a charity program through the Zoological Society of London, EDGE “is…funded entirely through grants and from donations generously made by members of the public. Everything that’s been achieved thus far has been dependent on this resource and the thriftiness of the EDGE team!”

The Critically Endangered kakapo is one of the few flightless island birds to have survived into the Twenty-first century, but its future is far from certain. Photo by Dr. Paddy Ryan. |

For such a young conservation program, the achievements have already been many: proof that the critically endangered Attenborough’s echidna still exists, the first video of Mongolia’s long-eared jerboa, the rediscovery of the Hispaniolan solenodon in Haiti, footage of India’s hermit-like purple frog, and conservation programs in various stages for a number of very vulnerable mammals and amphibians. With Fellerman’s dedication and hard-work, the team can soon begin a new phase in the program: saving the world’s most unique and vulnerable birds.

Fellerman discussed studying evolutionary biology, working in the field with birds on a Welsh island, the method used by EDGE, working on the EDGE bird list, and what it takes to be successful in conservation science in a February 2009 interview with mongabay.com, a leading conservation and environmental science news site.

YOUNG SCIENTIST PROFILE

Mongabay: How did you become interested in wildlife? What is your background?

Katrina Fellerman: I guess my answer is going to be similar to so many others, in that I can’t really remember a time when I wasn’t fascinated by wildlife. When I was really young, I shared a fantastic set of books with my sisters, crammed with pictures of the creatures common to urban and rural settings. I remember running around with the “in the garden” volume, determinedly trying to find and identify everything that lurked outside our house!

Fellerman doing a field study of common guillemots on Skomer Island, Wales. Photo by Katrina Fellerman. |

By the start of secondary school I was enjoying working at my local stables and was convinced I was going to be a veterinarian, because ‘that’s what people that liked animals did’! I thought my future lay in purposefully striding about farmyards in green wellies, treating sick farm animals a la All Creatures Great and Small (a TV series I probably spent far too much time watching; adapted from the books of British veterinarian James Alfred Wight, under the pseudonym James Herriot). It wasn’t until I appreciated the range of options actually available (and like everyone else, got hooked on Sir David Attenborough’s wildlife documentaries) that I realised my interests lay in zoology, rather than veterinary science.

Mongabay: What led you to decide to focus on evolutionary biology?

Katrina Fellerman: It’s an area I find fascinating; the diversity and abundance of species and the processes that drive their change and multiplication. Having touched upon it at school I knew I wanted to learn more, and so hunted for a degree that included a healthy dose of modules in this field – unsurprisingly, the conservation & ecology, population genetics and ‘evolution from molecules to species’ lectures ended up being my favourite.

I knew I wanted to continue my studies within this subject area, and so shortly after completing my zoology degree I took a Masters of Research in Evolutionary Biology and Systematics. As well as attending lectures in behavioural ecology and evolutionary processes, I got the chance to play around with insect DNA, as one of my research projects involved reconstructing the ‘evolutionary tree’ of glamorous seabird lice! All in all I’d have to say my interests stem from wanting to better understand – and thoroughly enjoying – this subject.

The cliff-nesting common guillemot. Photo by Katrina Fellerman. |

Mongabay: You’ve worked on a number of fieldwork projects too, what has been your favourite?

Katrina Fellerman: Working on Sheffield University’s (long-term) common guillemot study on Skomer Island, Wales, is still top of my list. Not only was the fieldwork absolutely brilliant (monitoring the survival, breeding success, chick feeding rates and diet, for a number of sub-colonies dotted around the island), the location itself was stunning.

Skomer is managed by the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales, and is a designated National Nature Reserve, a Site of Special Scientific Interest, a Special Protection Area, and is surrounded by a Marine Nature Reserve. Located off the Pembrokeshire coast, it is famous for its seabird colonies and is home to the world’s largest colony of Manx shearwaters. It boasts its own race of bank vole – the unique Skomer vole – and in May the island is completely awash with bluebells. I have very fond memories of getting up at sunrise and grabbing a speedy breakfast whilst watching the grey seals in the bay below the research quarters, before heading off to start the day’s work.

As well as studying cliff-nesting guillemots there was plenty of opportunity for watching puffins, razorbills, kittiwakes and fulmars; and at night there was the spectacle of tens of thousands of Manx shearwaters noisily returning to their burrows. I also got to meet and work alongside some pretty great people too.

Atlantic Puffin on Skomer Island, Wales. Photo by Katrina Fellerman. |

EDGE SPECIES

Mongabay: When did you first learn about the EDGE initiative?

Katrina Fellerman: I first encountered the Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) new EDGE of Existence programme on the BBC News website in January 2007, when I stumbled upon an article reporting its official launch. A couple of months later, I attended the “Saving Species on the EDGE: From Theory to Practice” scientific meeting held at ZSL, as I wanted to learn more about this initiative and the theory underpinning it. What I heard really resonated with me, and I left feeling excited and inspired… so when the opportunity to join the EDGE team later arose in 2008, I jumped at the chance!

Mongabay: Can you tell us what makes an animal an EDGE species?

Katrina Fellerman: Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered (so called “EDGE”) species are those that meet two criteria; they are species that are both:

- Evolutionarily Distinct (as determined by species’ relative positions within a reconstructed “phylogeny” or “evolutionary tree”) and,

- Globally Endangered (as designated by the IUCN Red List).

Lesser black-backed gull chick from Walney Island. Photo by Katrina Fellerman. |

To further explain, we use evolutionary distinctiveness (ED) as a species-specific measure of the relative evolutionary value of species – it is a way of apportioning conservation value according to a species’ phylogenetic position. Species with few or no close relatives on the ‘tree of life’ have the highest ED scores. If you can imagine a schematic of this tree, these species would be represented by ‘branches’ rather than ‘twigs’. The world’s number one ED mammal species is the duck-billed platypus – this bizarre looking egg-laying mammal is now the only surviving member of a family that dates back as far as the Cretaceous period (146-65.5 million years ago). Other examples of high scoring ED species include the phenomenally small bumblebee bat and the venomous solenodons of Hispaniola and Cuba. Again, these species are the last surviving representatives of entire families of mammals. Species such as these represent a disproportionate amount of unique evolutionary history, and so are more valuable in terms of evolutionary heritage. In addition to their distinct genetic makeup, these species tend to be unique with regards to appearance, behaviour, and the ecological niches they occupy: to put it bluntly, if lost, there would be nothing like them left in the world today.

Recently rediscovered in Haiti by EDGE the Hispaniolan solenodon is one of the world’s few poisonous mammals. Photo by Eladio Fernandez. |

The second criterion I mentioned relates to a species’ (current) threat status. Each species is assigned a ‘global endangerment’ (GE) score according to its designated IUCN Red List Category. These range from the highest scoring Critically Endangered category, through Endangered, Vulnerable, Near Threatened, to the lowest scoring category: Least Concern. Actual EDGE scores are calculated by combining ED and GE values. Together, they provide us with a measure of the expected loss of evolutionary history per unit of time. EDGE species are those which have an above average ED score and are threatened with extinction (i.e. are Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable).

I should say that more detailed information regarding actual EDGE methodology (and access to the published methods paper) is available on our website at www.edgeofexistence.org , and I’d definitely encourage those interested in finding out more to take a look.

Mongabay: How does EDGE differ from other conservation initiatives?

Katrina Fellerman: EDGE is unique in its framework for prioritising species conservation action – it is the only global conservation initiative to focus specifically on those threatened species that encapsulate a significant amount of unique evolutionary history.

Mongabay: What can the general public do to help the EDGE program and its species?

Katrina Fellerman: We are very much dependant on support from the public and the tremendous help they provide in both promoting and funding EDGE’s work.

EDGE fellows at Whipsnade. Fellerman is the fifth from the right in the back row. Photo by Zoological Society of London. |

As you know, the programme’s overarching aim is to prevent extinction of the world’s most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered species. The first step towards achieving this has been to raise awareness of these species, their plight, and the urgent conservation actions required to safeguard their future. The launch-pad for this has been the development of an interactive website featuring:

- comprehensive EDGE species accounts,

- the programme’s methodology,

- details of the conservation projects we have underway and the “EDGE Fellows” (young, aspiring in-country scientists) we are supporting in carrying them out,

- a community member facility,

- the EDGE blog, and

- the EDGE forum.

In this regard, the public have been invaluable in helping us raise awareness of the programme. Through their visits to our website, contributions to our knowledge base, involvement with online discussions and encouragement of others to do so, they have been incredibly supportive, and we hope they continue to take an active role in our work.

Often people don’t realise that ZSL is actually a registered charity, and the EDGE of Existence programme is therefore funded entirely through grants and from donations generously made by members of the public. Everything that’s been achieved thus far has been dependent on this resource and the thriftiness of the EDGE team! For this reason, we are incredibly appreciative of any donations received and the fund-raising activities that have been organised by members of the public – it’s their continued support that enables EDGE to do the vital work it does.

Of course, non-profits and charitable organisations such as us aren’t helped by the current economic climate, but regardless, the EDGE programme has exciting plans for 2009. This year, in addition to (continuing) contributing to the research and conservation of EDGE’s 20 Focal Mammal and Amphibian species, we will be organising the second annual EDGE Fellows training course in London, establishing new EDGE projects in China, and developing marvellous EDGE Birds!

We also hope to encourage more people to become “EDGE Champions”. These are individuals that have generously volunteered their services to raise money directly for the programme, or champion EDGE’s work by bringing it to the attention of new audiences and encouraging further participation. Details of our fund-raising Champions are available on our website, along with suggestions for ways in which people can get involved. I’d be amiss if I didn’t also take this opportunity to mention our donations page, which has been set up to allow contributions to either the programme as a whole, or individually to EDGE Mammals, EDGE Amphibians, and the EDGE Fellows.

Mongabay: Do you have a favourite mammal and amphibian from the EDGE lists?

Katrina Fellerman: Well, I’ve had a soft spot for the monk seals (Monachus) since my undergraduate dissertation which investigated the factors attributed to their decline, and the Mediterranean monk seal is currently number 27 in the top 100 EDGE mammal species list. I’m also something of a fan of the blue whale, ranked at number 88. It’s the largest mammal ever known to have existed and dinosaurs aside, it was seeing the life-size model of this species that blew me away the first time I visited London’s Natural History Museum! Despite this, I’m going to have to say the beautiful golden-rumped elephant shrew (number 46) is my favourite EDGE mammal species. The males have thickened patches of skin on their rumps called “dermal shields” that are thought to protect them from aggressive bites from other males, and unusually for such a small mammal, this species is monogamous. Over the summer, I was fortunate enough to meet Grace Ngaruiya (our Kenyan EDGE Fellow) who has been surveying for this species, and I think it must have been her anecdotes about this fascinating animal that made it my number one!

The largest of Africa’s elephant shrews, neither elephant nor shrew, this species is classified as Endangered. Photo by Galen Rathburn. |

As for amphibians… I’m very impressed by the Chinese giant salamander, the largest living species of amphibian; which at the maximum length of 1.8 metres would ‘stand’ taller than me! The aquatic olm is another contender: it’s Europe’s only cave-adapted vertebrate and is capable of surviving without food for up to an incredible 10 years. However, I think my favourite amphibian species has to be the Chile Darwin’s frog. Ranked at number 45, this is one of only two species of ‘mouth brooding’ frog in the world. Males will guard fertilised eggs until hatching, whereupon the young tadpoles are swallowed so that they can continue their development within the adult’s vocal sac! Not seen in the wild since 1980, EDGE recently participated in a three-week expedition to central Chile to survey for this possibly extinct species and clarify the reasons for its decline. Helen Meredith (the EDGE Amphibians coordinator) and the team are currently pouring over data and will be posting their findings on our blog soon.

THE EDGE BIRD LIST

Mongabay: What sources do you use for researching the bird species?

The Chinese giant salamander has been devastated by habitat loss, pollution, and over-harvesting as a delicacy in China. Photo courtesy of International Cooperation Network for Giant Salamander Conservation. |

Katrina Fellerman: Questions relating to EDGE Birds are tricky, as much is under wraps at present! But I’ll divulge what I can… In terms of resources, ZSL’s library is one of the major zoological libraries in the world and so is a pretty good place to start. In addition to hogging as many of ZSL’s books and journals as possible, I make extensive use of reputable web-based resources, most notably Birdlife International’s species factsheets. Birdlife have also been kind enough to allow me to make use of their library facilities. For little known species, I try to establish whether there are any researchers actively studying them that could be contacted for further information.

Mongabay: What particularly interesting and unusual bird species have you come across?

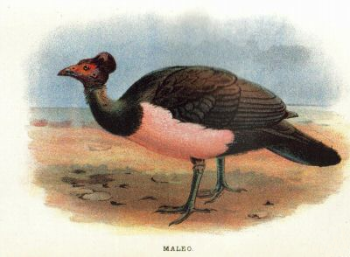

Katrina Fellerman: I’m currently working my way through the top 100 EDGE bird species, so invite you to ask me again at a later date! Without spoiling all the surprises, I’d have to say that the Asian crested ibis and its curious tar-like secretions, the nocturnal kakapo and its incredible faculty for weight-gain, and the maleo and its cunning use of geothermal energy for incubation purposes, stand out for me!

The ghostly olm is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Photo by Arne Hodalič. |

Mongabay: What are the major threats to birds worldwide?

Katrina Fellerman: BirdLife International is the official IUCN Red List Authority for birds. In their latest assessment in 2008, they found that a staggering one in eight of all bird species is threatened with global extinction. Sadly, the culprits are all too familiar. As human populations continue to expand, the need for greater resources has intensified pressure on global ecosystems. Loss and degradation of habitat (through, for example, agricultural land-uses, residential and commercial development, logging, replacement of natural forest with monocultural plantations, energy production and mining) is, unfortunately, a common threat. Overexploitation by man for both food and the pet trade has also played its part, while invasive alien species have had devastating consequences for many small island birds. Add to this the impact of climate change and disease, and its fair to say that birds, like so many taxonomic groups, have had a pretty tough time of it.

Mongabay: Is EDGE planning to partner up with any particular organizations for bird conservation?

Katrina Fellerman: Very much so. One of the major aims of the EDGE programme is to help increase the capacity of in-country conservation organisations and scientists, to conserve their own biodiversity. To this end we plan to work with a range of different national and international conservation organisations to research and conserve EDGE Birds – beginning with the ‘first round’ of’ EDGE Birds’ focal species.

A possible EDGE bird, the Maleo is endemic to the island of Sulawesi. Lithograph from Lloyd’s Natural History of Game Birds. |

Mongabay: As an evolutionary biologist, if you could bring back any bird from extinction to study which would you choose and why?

Katrina Fellerman: Ever since working on Skomer I’ve been really taken with the alcids or ‘auks’ (the alcidae family includes the guillemots, puffins, auklets and the razorbill), so for me it would have to be the great auk. Easily recognised by its immense size (75-85cm), striking bill, and upright stance, this magnificent black and white bird met its final fate on the 4th June, 1844. The largest member of the alcid community and the only flightless one, this species was an expert swimmer and a specialised fish-feeder. Once widely distributed across the North Atlantic (from islands in Newfoundland in the west, to Norway in the east), slaughter by humans for food, eggs, and their down, possibly coupled with vulnerability to climatic changes, led to their demise.

The great auk was hunted to extinction, the flightless bird was over two-and-a-half feet tall. Painting by J.G. Keulemans. |

Mongabay: When should we expect the EDGE Bird list?

Katrina Fellerman: I’m currently working away ‘behind the scenes’ on EDGE Birds, and can’t reveal too much at present. Suffice to say, we’re considering launching in 2009, and remain huddled in discussion over the opportune time to do so!

Mongabay: Are there particular educational or promotional programs that you are working on?

Katrina Fellerman: EDGE is already incorporated into the Educational programme at ZSL, and in 2009, an outreach programme will be developed whereupon members of the team will get the opportunity to visit schools and discuss EDGE’s work with children, face to face. The team is also very keen on developing an educational ‘arm’ to the EDGE of Existence website, dependent on the resources available. Our first steps will be the creation of downloadable EDGE species factsheets and project worksheets that teachers can use in class, followed by the development of online games as learning tools. These will initially be designed to target children at primary school, with later expansion to older age groups.

In terms of generally getting EDGE’s message across to younger people, Dr. Jonathan Baillie and Marilyn Baillie recently launched a book aimed at 7-12 year-olds entitled “Animals At The Edge: Saving The World’s Rarest Creatures”. This introduces a selection of EDGE species, and explains the work we do and why it is so important in a way that we hope captures children’s imagination.

As for our promotional work, we are constantly reviewing ways in which we can increase ‘web traffic’ and raise EDGE’s profile in the public domain – of course media interest always helps! We have a blog which is regularly updated with the latest developments from the EDGE team, reports from our EDGE Fellows from out in the field, and which highlights relevant news articles and the latest significant findings. Members of the public can also get involved by adding their comments. We have a regular newsletter that is emailed to our supporters (which is also available on the website) and an “EDGE Forum”; set up to encourage discussion between interested parties. Just for fun, we created a selection of festive e-cards that were available on our website over the Christmas period. There were ten EDGE species to choose from, including the long-eared jerboa and slender loris, and we’re now considering designing more for other public holidays and events.

The bumbleebee bat was classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN in 2008. Photo by Medhi Yoku. |

ACHIEVING SUCCESS IN CONSERVATION

Mongabay: What advice would you give a student who is considering pursuing biology and/or conservation for a career?

Katrina Fellerman: It’s true it is increasingly difficult to break into conservation work. Faced with such a competitive environment, you need more than just your hard-earned degree(s) to stand out to prospective employers nowadays. A good way to do this is to acquire additional skills outside of an academic degree – the more ‘strings to your bow’, the better – and of course there’s no substitute for having ‘hands on’ experience. For instance, in addition to a strong grounding in your particular field of interest (be that a degree in Biology, Zoology, Conservation Science, etc.), you could look to acquire other skills, according to your aptitudes and preferences. If you’re particularly adept at mathematics and data analysis, you could consider seeking further qualifications in statistical analysis, or training in the use of GIS, remote sensing techniques, computer modelling, etc. Similarly, students with language skills will always be valued given the international nature of environmental and conservation work. Other routes into conservation-orientated work include the law, politics (you could be directly involved in informing government policy), sociology, or anthropology.

Fellerman working with the lesser-black backed gull in the field. Photo courtesy of Katrina Fellerman. |

The ability to clearly explain the findings and relevance of a scientific study or policy issue directly to the public, or conversing with the media, are also highly prized skills. If you’re a strong communicator, consider building on this – education of future generations is fundamental to changing behaviours, thereby allowing effective and sustainable conservation, while engaging with the media is integral to conveying the importance of this work to as wide an audience as possible. And for those that prefer to be out in the field collecting raw data, consider whether a basic knowledge of botany, scuba diving qualifications, first aid, electrical or even carpentry skills could prove useful.

In terms of gaining practical experience, seeking voluntary work and internships is a really good way to do this, provided you choose carefully and are clear on what you hope to gain from the position. There are a lot of amazing opportunities out there, and you want to be sure you make the most of them. In addition to developing new skills you’ll be in a good position to hear about up-and-coming vacancies, and are, of course, also demonstrating your commitment to this line of work. Be persistent: it can be incredibly frustrating, so patience and determination are key. Finally, be opportunistic – sometimes it comes down to just being in the right place at the right time, and you really don’t want to let a chance opportunity pass you by. It may take time, but the reward is working in a job you feel really passionate about, alongside like-minded people.

LINKS

General:

- The Zoological Society of London: http://www.zsl.org /.

- The Edge of Existence website: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/.

- EDGE methodology: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/about/edge_science.php /.

- EDGE Champions: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/support/champions.php.

- Supporting EDGE: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/support/champions_information.php

and http://www.edgeofexistence.org/support/default.php

Species Accounts:

- Blue whale: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/mammals/species_info.php?id=88.

- Chile Darwin’s frog: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/amphibians/species_info.php?id=590.

- Chinese giant salamander: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/amphibians/species_info.php?id=547.

- Golden-rumped elephant-shrew: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/mammals/species_info.php?id=46 /.

- Mediterranean monk seal: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/mammals/species_info.php?id=27.

- Olm: http://www.edgeofexistence.org/amphibians/species_info.php?id=563.

Related articles

Saving forgotten species: An interview with Carly Waterman, Program Coordinator of EDGE

(02/28/2008) In January 2007 a new conservation initiative arrived with an unusual level of media attention. The attention was due to the fact that the organization was doing things differently—very differently. Instead of focusing their efforts on the usual conservation-mascots like the panda or tiger, they introduced the public to long-ignored animals: photos of the impossibly unique aye-aye and a baby slender loris wrapped around a finger appeared in newsprint worldwide. The new initiative EDGE (Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered), launched by the Zoological Society of London, was not concerned with an animal’s perceived popularity, rather the chose their focal species on a combined measurement of a species’ biological uniqueness and its vulnerability to extinction. Consequently, they hoped to make celebrities out of animals (big and small) most people had never heard of: the hairy-eared dwarf lemur, anyone?

Photos of the top 10 most threatened amphibians

(01/21/2008)Due to numerous factors—including habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and chytrid fungus—amphibians are probably the most threatened taxon in the world, with more than one-third of species at risk of extinction. “Tragically, amphibians tend to be the overlooked members of the animal kingdom, even though one in every three amphibian species is currently threatened with extinction, a far higher proportion than that of bird or mammal species,” said Dr Jonathan Baillie, head of the EDGE organization which has just established an amphibian conservation program.

Saving the beautiful – and the ugly – creatures of the world: Why the EDGE Matters

(08/30/2007)

Allow me to wax poetic about the world’s newest wildlife organization, EDGE. I must admit I’m a little in love. This singular organization was founded in January as a part of the London Zoological Society. Its basic tenants remain similar to other endangered species programs: survey populations, set up conservation programs, work with local governments and communities to ensure protection. However, what is unique about EDGE is not their approach to saving species, but rather the species they choose to focus their efforts on. This year they have selected ten mammalian species: the Yangztee River Dolphin, Attenborough’s Long-Beaked Echidna, Hispaniolan Solenodon, Bactarian Camel, Pygmy Hippopotamus, Slender Loris, Hirola, Golden-rumped Elephant Shrew, Bumblebee Bat, and the Long-eared Jerboa.