The Colorado River vanishes before it reaches the Sea of Cortez in all but the wettest years. Companies in California and the southwestern U.S. have diverted its once-vibrant flow to quench their thirst for water and power. Now, a new study in the April 2008 issue of the journal Biological Conservation reports that the dwindling of this major artery has changed the way some marine fish in the Gulf of California grow and develop.

The study focused on the totoaba, a giant endangered fish that once thrived in the region. The damming of the Colorado River has choked the natural flow of sediment and nutrients, causing sandbars and beaches to erode. Similarly, a protective estuary in the Gulf of California once formed by the river no longer exists, leaving few places for young totoaba to find food and hide from predators. According to the study, these drastic habitat changes — along with pressures on the totoaba from overfishing — have made it impossible for the young fish to grow quickly enough for the population to recover.

Accidental harvest: Though protected, totoaba (above), as well as the small porpoise known as the vaquita (below), fall prey to fishing nets in the Gulf of California — just another factor stifling the recovery of both species. (Credit: Omar Vidal) |

Weighing in at nearly 300 pounds, the totoaba, a fish in the drum family, was a tasty staple in the diet of peoples in what is now Mexico for millennia before the fishery collapsed in the mid-20th century. In 1975 Mexico designated the totoaba as an endangered species and closed the fishery, attributing the decline to overfishing. However, the totoaba population has not bounced back since the ban. Shrimp and gillnet fishermen probably take a share of protected totoaba and don’t report the by-catch to authorities, but in the absence of a directed fishery, biologists expected the totoaba population to climb.

Recently, a team of scientists hypothesized that the difference might have something to do with the loss of fresh water from the Colorado. This river flow once infused the Gulf with nutrients and food sources, creating the estuary that was prime habitat for young totoaba. The team, led by University of Washington aquatic biologist Kirsten Rowell (formerly based at the University of Arizona), thought the construction of Hoover Dam in 1935 might have triggered the problem.

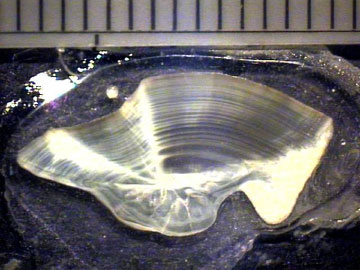

Rowell and her colleagues compared the ear bones — or otoliths — of fish that lived after construction of the dam with totoaba otoliths found in the refuse heaps, or middens, of civilizations dating back 1,000 to 5,000 years. The team sliced the bones in search of clues about the comparative growth rates of these animals. “They grow concentrically,” Rowell said, “so it’s sort of like taking a jawbreaker and cutting it down the middle.” Analogous to the rings of a tree, thicker bands appear in the otoliths during years of more growth.

A sectioned otolith, showing its growth rings. (Credit: Kirsten Rowell, University of Washington) |

From this comparison, the scientists found that young totoaba had grown more quickly if they lived before the damming of the Colorado. Further, they discovered those “pre-dam” fish matured sooner — in some cases, as many as five years earlier than their “post-dam” counterparts. That’s a major change for a fish with a lifespan of up to 25 years.

Fishing wouldn’t cause that upheaval in life history, Rowell said, so her team guessed that it might have something to do with losing the estuary created by the Colorado River. An estuary, like a pot of soup, depends on the mixing force of flowing water. River water brings its own nutrients from the interior of a continent, but it also stirs up particulates from the river bottom when it approaches the sea, making a life-giving broth. Some 60 percent of fish that end up on American tables spend part of their lives in these fish nurseries around the world, where food is more abundant. Critically, vulnerable baby fish can find shelter from predators among more numerous plants in healthy estuaries.

Since the Gulf of California estuarine habitat started to disappear in the 20th century, younger totoaba haven’t been able to find food as easily. As a result, they were smaller than pre-dam fish of a similar age. Over generations, this also led the fish to start breeding at an older age. “It’s a general rule in fisheries that the larger you are, the more resources you have to give,” Rowell said. The post-dam fish, smaller than their forebears, now don’t have enough energy to spare to reproduce until later in life.

All of this becomes doubly concerning when the pressure from indiscriminate fishing tactics like gillnets cull many young fish. A century ago, such fish might have already spawned and left a new generation to ply the waters of the Sea of Cortez. But today, adolescent totoaba snagged in nets aren’t as likely to be mature enough to have bred.

Because of the relentless drawdown and diversion of the Colorado, the estuary may be beyond saving. However, the U.S. Department of the Interior did attempt to restore some of the lost habitat in a controversial move on March 6. The department, which operates the Glen Canyon dam above the Grand Canyon, released some of its water to flush sediment downstream. But many environmental groups criticized the action as destructive, arguing that this simulated flood — much bigger than a natural spring flood would be — was too concentrated and would likely be too harsh for the sediment to stick and form the sand bars. The results still aren’t conclusive.

A totoaba otolith. (Credit: Kirsten Rowell, University of Washington) |

The impact of this research extends beyond the fortunes of a single species, Rowell said. The implications might require some tough choices as the global community faces potential food shortages, she added: “Fisheries seem like a really great way to get protein. Are we going to give water to this ecosystem that may fuel fisheries? Or are we going to build more houses?” Population growth in water-starved areas only increases the need for freshwater and hydroelectricity, Rowell said.

“This is an example of something that’s happening all over the world,” said Jorge Torre, a conservation biologist and executive director of the conservation group Comunidad y Biodiversidad (COBI), based in Guaymas, Mexico. Torre called the research “a very nice proof” that altering an ecosystem, even from great distances in space and time, can dramatically affect the species that call it home.

It may be too late to transform the Colorado River delta back into the habitat it once was, Torre said: “We need to be practical — we’re never going to have that water again.” But he noted that as the world population grows, fresh water and the fish it supports will become more precious resources. Torre hopes policymakers will pay attention to the hard lessons learned from the totoaba.

John C. Cannon is a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.