- Wilmar International’s No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation policy, announced ten years ago, marked a significant milestone in environmental conservation by prohibiting deforestation, peatland destruction, land-grabbing, and labor abuses in their global supply chain, impacting thousands of palm oil companies.

- The policy, a result of global campaigning and intense negotiations, contributed to a dramatic reduction in deforestation for palm oil by over 90%, influencing other industries and contributing to the lowest deforestation levels in Indonesia, as well as progress in Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, and tropical Africa, argues Glenn Hurowitz, the Founder and CEO of Mighty Earth, who led the negotiation with Wilmar.

- Hurowitz says this “success story” highlights the importance of private sector involvement, effective campaigning, diligent implementation, the necessity of continuous effort, and the insufficiency of data alone in driving change.

- This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the author, not necessarily of Mongabay.

Ten years ago this month, I stood with the CEO of Asia’s biggest agribusiness, Wilmar International, to announce the company’s new No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation policy. It banned deforestation, destruction of carbon rich peatlands, land-grabbing and labor rights abuse throughout their vast global supply chain – meaning that in one stroke, thousands of palm oil companies would have to comply or risk losing access to one of the biggest customers.

Because Wilmar single-handedly controls more than a third of trade in the commodity, the policy was a big deal. It provided hope that the era of wanton forest destruction and climate pollution might come to an end. The policy was hard won, the product of a global campaign across continents combined with five months of roller-coaster negotiations.

Despite our excitement, we knew that what mattered was translating it into action on the ground in Asia, Africa, and beyond. We didn’t know for sure that would happen.

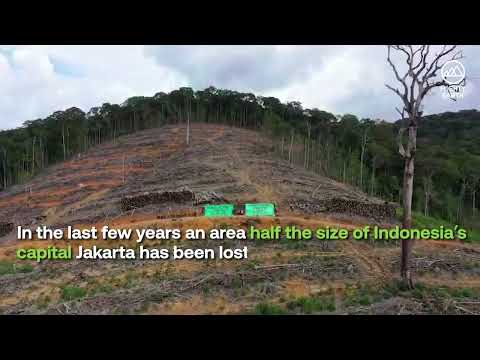

But happen it did. Over the next five years, deforestation for palm oil would plummet more than 90% and stay at low levels to this day. The paper and rubber industries, facing similar campaign pressure, would achieve similar progress. Overall, this action contributed to Indonesia reducing overall deforestation to the lowest level on record, as well as progress in Malaysia and Papua New Guinea. In addition, we and our allies were able to persuade the companies to apply their policies to protect the forests of tropical Africa, where the industry had been planning a whole new generation of plantations. This expansion in scope likely avoided millions of acres of additional deforestation.

Overall, the transformation avoided more than a gigaton of climate pollution over a decade – and saved thousands of orangutans, tree kangaroos, forest elephants, and gorillas from having their homes bulldozed. It also allowed Indigenous communities across the forest frontier to gain stronger recognition of their rights and in many cases hang onto their land.

What made this transformative success possible – and what can we learn from it as countries work toward protecting Nature and transforming food systems?

Lesson 1: The Private Sector Matters.

For many years, conservation efforts had focused largely on government, and to a lesser extent local communities. Make no mistake – governments are critical actors when it comes to protecting natural resources, and Indigenous communities are typically their best defenders. But in many of the countries where deforestation for agricultural commodities was happening, a combination of corruption and weak governance meant that government wasn’t doing its job to protect forests, in part because many governments don’t respect Indigenous land rights. Some governments were even complicit in driving deforestation and land-grabbing.

Paradoxically, in many cases, the very companies most responsible for millions of acres of deforestation were also the ones best positioned to stop it. They were the ones with the buying power and the commercial networks to set conditions for how agriculture was done. In many ways, they acted as modern agricultural extension services. And so, when Wilmar adopted its No Deforestation policies – and then when over the next year the traders representing more than 90 percent of palm oil trade did the same – change happened. These companies had the power to set the terms of business. Getting profit-seeking companies to change without new regulation wasn’t easy – but it was possible. And in many cases it was more politically feasible than persuading government to quickly ramp up conservation.

Lesson 2: Campaigns Work – Including in Asia.

When we started to work on palm oil and rubber, the conventional wisdom was that it would be very difficult to change these industries. At least 60% of demand for these products was in developing Asian markets that had not demonstrated much concern for the sustainability of imported products. That conventional wisdom was understandable: the primary market for palm oil was as for cooking oil – and for billions of poor people, low prices translated to full bellies.

However, what we found in our research was that a handful of companies like Wilmar dominated the trade in Asia. But for these companies, developed countries were their emerging markets. They wanted to diversify their customer base so they could sell higher-value products, and not be as subject to many developing countries’ suddenly shifting protectionist tariffs.

As a result, Western customers and investors, it turned out, actually had a lot of leverage. Pressure from big Western companies like Unilever and Kellogg’s was part of the reason why the palm oil industry changed.

But they weren’t enough. Even after the largest companies adopted strong conservation policies, many rogue actors remained, and most were based in Asia.

To succeed, we had to launch campaigns focused on those companies too.

As a result, we moved quickly to establish partnerships with local groups and campaigned together in Korea, Japan, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and elsewhere. For instance, we caught a single Korean company destroying more than 70,000 acres of forest. We were able to combine domestic and international pressure to get them to rapidly cease bulldozing.

And the great news is that we were able to replicate that model over and over again. While there are still a small handful of rogue actors continuing to bulldoze forests, such as the paper and palm conglomerate Alas Kusuma, they are collectively causing just a tenth of the annual damage they used to.

Lesson 3: Implementation, Implementation, Implementation

One of the critical ingredients that ensured this these commitments didn’t remain just policies on paper was the participation of credible implementation partners. Even the largest companies lacked all the expertise and background needed to drive commitments. The fact that organizations like Earthworm could guide the companies on how to drive implementation through their supply chains made an enormous difference, as did monitoring by AidEnvironment and many others.

As important as that engagement was, however, the first two years after the forest policies were announced, we continued to see too many companies destroying forests and abusing human rights – but still being able to sell their products on global markets. The large traders had improved their performance, but clearly were not implementing it fully. They were a bit like pre-conversion Saint Augustine: “Lord, make me good, but not yet.” They knew they had to change, but they hadn’t fully got down to the business of actually doing so.

However, we found that when we alerted the companies to deforestation in their supply chains, they acted. Part of the reason was that our alerts provided the political cover they needed. Executives told us they could say to suppliers that it wasn’t them requiring action, but that they were being forced to do so by Mighty Earth and allies like Rainforest Foundation Norway and Greenpeace.

We decided to systematize the process, and established our Rapid Response satellite monitoring process where we use resources like Global Forest Watch satellite alerts, overlay them with Planet and other resources, and work with MapHubs and others to refine the data. Then we file alerts with the companies, identifying suppliers who are linked to deforestation. This system, still in operation today, ultimately drove more than 250 supply chain discontinuations. Most importantly, it created an expectation throughout the industry that deforestation would cause a loss of market access and investment. Along with complementary monitoring, alerts, and campaigns by partners, we believe this system was one of the key interventions behind the success in protecting forests.

Lesson 4: Data Isn’t Enough.

The world is awash in data, but data alone doesn’t save forests or suck carbon out of the atmosphere. The Rapid Response initiative simply wouldn’t have succeeded without the political will to ensure that companies acted when we filed alerts.

At one level, we needed the “outside game” of public campaigns to create the credible threat of commercial, financial and reputational consequence, so that the “inside game” of monitoring would translate into action.

But we also needed very specific implementation plans to make sure political translated into action on the ground.

And so, we convened the industry to translate policy into plans. This involved dozens of individual and group meetings to hammer out commitments to respond within 48 hours to any deforestation or human rights alert. It was hard work, and involved lots of challenging meetings across Southeast Asia. But it ensured that deforestation would be stopped at the 10-acre level before it got to the 10,000-acre level. Getting those commitments involved long hours of negotiation with large numbers of companies. But it ultimately worked and created the political conditions for success.

Lesson 5: We’re Not Done.

The model worked. And along with similar success in reducing deforestation for paper by allies, inspired similar action in the rubber industry. We are now deploying this model of industry transformation elsewhere. We’re working to get the meat industry, the world’s largest driver of ecosystem destruction, to end deforestation, tackle methane pollution, and increase plant-based and other alternative protein. We’re working to drive decarbonization by the auto and steel industries. In all these other fields, it’s been so helpful to point out how the once notorious palm oil industry has made extraordinary improvements that once seemed impossible.

The work is not complete, however. There are still some rogue companies bulldozing forests. And despite the progress in the private sector, there are still over 200,000 hectares of deforestation per year in Indonesia alone driven by unsustainable infrastructure, mining, fire, smallholder agriculture, and ill-conceived development projects.

Some of these challenges require scaling the kinds of interventions described above – and ensuring companies are enforcing their policies across different commodities (it doesn’t matter to forests whether a company is doing it for palm oil, gold, nickel or paper). Some require different interventions like massively boosting financial investment in conservation and restoration. For that reason, our biggest focus across Southeast Asia and the Congo Basin is getting companies to invest in conserving and restoring an area at least as great as the 30,000 square miles of forest that were destroyed for palm oil alone before the companies adopted their conservation policies. It’s an exciting vision: by restoring forests and peatlands, these lands could provide new habitat for highly endangered species like Sumatran tigers and birds of paradise in their thousands – and suck additional gigatons of carbon out of the atmosphere. It could also mean truly sustainable development opportunities for the many Indigenous groups whose land was stolen.

Driving companies and governments to act with sufficient scale and ambition to bring Asia and Africa’s battered ecoystems back to life may seem daunting. But the success of the palm oil industry in stopping deforestation shows that even radical transformations to the status quo are never impossible where the political will, and the behind the scenes resolve exists.

Healing the damage and bringing Asia and Africa’s Nature back to life is the great goal now, and one whose success I hope to be able to report on a decade hence.