- The Indonesian fisheries ministry issued a decree earlier this year introducing a quota-based fisheries management policy aimed at maximizing state revenue from the sector.

- A new study, however, has found that the new policy is unpopular with fishers, who say it reduces the role of local authorities and fishing communities.

- Local stakeholders’ responses also suggest the policy only benefits large-scale investors and commercial fishers, who are perceived to have a high negative impact on the environment.

- Indonesia’s fisheries sector plays a major role in the global seafood supply, with the country home to some of the world’s richest marine biodiversity.

JAKARTA — A quota-based fisheries management system that the Indonesian government introduced earlier this year has already run up against opposition for undermining the role of local authorities and fishing communities, a new study shows.

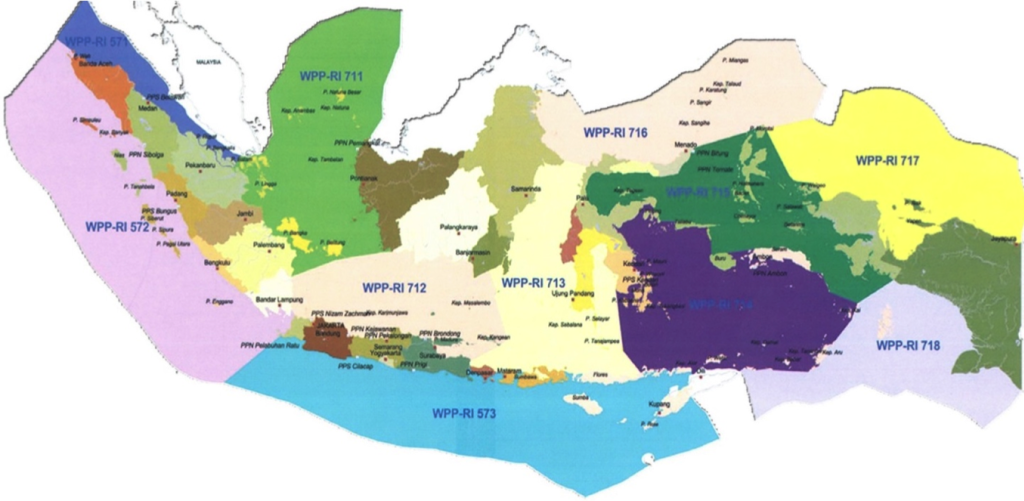

The study, published in the journal Ocean & Coastal Management, focuses on fisheries management area (FMA) 718, which covers much of the southeastern waters of the country, to review the challenges and potential of the new policy.

The researchers, from the Bogor Institute of Agriculture (IPB), conducted focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with local authorities, fishing communities and the private sector in Merauke and the Aru Islands. They found that these local stakeholders were pessimistic about the expected benefits from the new policy as their roles would be reduced.

“The underlying perception is that QBFM policy, as it stands, is driven solely by the ambition to enhance national economic and political stability,” they wrote. “This approach observes the interests of the primary ecosystem health, neglects community-based management, and worsens the potential for local anglers to catch fish.”

The lack of control and management by the local community would likely lead to the new policy only benefiting large-scale investors and commercial fishers, which are perceived to have relatively high negative impacts on the marine environment, the paper adds.

The quota-based fisheries management policy was introduced in March this year, aimed at maximizing state revenue from the fisheries sector. A key policy change from the previous policy is the introduction of quota-based capture for industrial, local and non-commercial fishers in six fishing zones that cover the archipelago’s 11 FMAs.

Study lead author Mukti Aprian said Merauke and the Aru Islands, in FMA 718, were both priority areas for fisheries development and have high potential for fisheries, but they lacked support in realizing that potential.

“The unsuccessful implementation of Indonesia’s previous policy and this policy breakthrough has prompted us to examine the impact on fisheries stakeholders,” the study says. “Additionally, we strive to identify the most suitable approach for marine and fisheries policy in Indonesia.”

FMA 718 in particular is known for various conflicts, ranging from disputes over the use of different types of fishing gear, to border disputes, to social conflicts associated with the arrival to the area since 2017 of commercial trawl fishers competing with local artisanal fishers.

The paper noted that while the quota-based fisheries management policy had lots of potential to address these issues, previous studies had instead revealed its downsides: unequal fishing rights, suboptimal catch and failure to meet quotas, potential dynamics in the fishery product market, and being strongly tied to fisheries market value.

“The main problem in fisheries policy in Indonesia is the consistency and distribution of policies,” the study says. “Fisheries and marine policies in Indonesia still prioritize short-term economic and political interests, even in some cases relying on foreign donor funding. It is these types of conditions that ultimately lead to local communities’ distrust of newly-formed national policies.”

The new capture quota is based on the potential fish stocks and total allowable catch (TAC). The previous policy allowed all fishing operators — from artisanal to industrial — to catch as much fish as they wanted as long as the total capture did not exceed the TAC, capped at 80% of the estimated fish stock. The new quota system will allocate a percentage of the TAC to each category of fisher.

Those affected are industrial, local and noncommercial fishers, while small fishers are exempted from the quota. In addition, industrial fishers are not allowed to operate within 12 nautical miles (22 kilometers) of the coast. Indonesia’s fisheries ministry says this approach should help reduce pressure on fish stocks and maintain their sustainability, while also encouraging and benefiting small fishers, who make up the majority of the country’s fishers.

These key changes have raised concerns among some marine conservationists and defenders of artisanal fishers’ rights, who say the new policy is mostly oriented toward the large-scale exploitation of Indonesia’s marine resources when more than half of fishing zones in the country are already “fully exploited.”

The latest data released by the fisheries ministry put Indonesia’s estimated fish stocks at 12 million metric tons, down almost 4% from the 12.5 million metric tons estimated in 2017. The data also show that 53% of the country’s FMAs are now deemed “fully exploited,” up from 44% in 2017, indicating that more stringent monitoring is required.

The fisheries ministry has acknowledged that compliance among fishing companies in Indonesia is low. The ministry has officially registered just 6,000 fishing permits, but the transportation ministry records some 23,000 permitted vessels.

Indonesia is the world’s second-biggest marine capture producer, after China, harvesting 84.4 million metric tons of seafood in 2018, according to the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The country’s waters support some of the highest levels of marine biodiversity in the world, and the fisheries industry employs about 12 million Indonesians.

Indonesia’s wild capture fisheries employ around 2.7 million workers; the majority of Indonesian fishers are small-scale operators, with vessels smaller than 10 gross tonnage. Under the business-as-usual scenario, the country’s capture fisheries is projected to expand at an annual rate of 2.1% from 2012 to 2030.

Basten Gokkon is a senior staff writer for Indonesia at Mongabay. Find him on Twitter @bgokkon.

See related from this reporter:

Rule change sees foreign investors back in Indonesia’s fisheries scene

Citation:

Aprian, M., Adrianto, L., Boer, M., & Kurniawan, F. (2023). Re-thinking Indonesian marine fisheries quota-based policy: A qualitative network of stakeholder perception at fisheries management area 718. Ocean & Coastal Management, 243. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106766

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.