- An Ecuadorian naturalist collected the bald-faced Vanzolini saki in 1936 along the Eiru River. His record was the first and last known living evidence of the species.

- In February 2017, an expedition called Houseboat Amazon set out to survey the forest along the Juruá River and its tributaries, with the hopes of finding the Vanzolini saki.

- After just four days, the team spotted one leaping from branch to branch in a tall tree by the Eiru River.

- The saki’s habitat is still fairly pristine, but the scientists worry its proximity to Brazil’s “arc of deforestation” and hunting pressure may threaten the species in the future.

EIRUNEPE, Brazil – An expedition exploring a remote watershed in the western Amazon has uncovered the first living evidence of a species of monkey not seen alive by scientists in 80 years, according to saki expert and expedition leader Dr. Laura Marsh. The account of the discovery will be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Oryx.

Houseboat Amazon, a major biological expedition wrapped up earlier this year in the Upper Juruá watershed located in the Brazilian states of Acre and Amazonas. The three-month expedition was the first survey of primates and other mammals in the watershed in more than 60 years.

The main goal was to find the missing bald-faced Vanzolini saki, a large monkey with a long fluffy tail and golden fur on its arms and legs. Ecuadorian naturalist Alfonzo Olalla collected this species in 1936 along the Rio Eiru. His record was the first evidence of the Vanzolini saki and no other living evidence had been found in the area since.

Primatologist Laura Marsh spent ten years updating the saki monkey taxonomy. Earlier this year, Marsh contracted a two-story houseboat in Cruzeiro do Sul to serve as the field station for the expedition, and brought together a team of seven primatologists from Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and the U.S. plus guides, drone operators, and photographers. On February 1, Houseboat Amazon set off to search for the missing monkey.

.jpg)

After stocking up on supplies at the shops along a single paved road in Eirunepé, they navigated two days up the Rio Eiru, a tributary of the Juruá River. A small riverside community on the border of the Kulina Indigenous Reserve served as the first of many base camps. Even though it had been 80 years since scientists encountered the saki monkey in this area, the team was hopeful they would find the lost primate.

They didn’t have to hope very long. On day four, team members motored up a side channel in a metal canoe, traveling several hours against the current with the aid of an ear-piercing motor that echoed off the trees. At 27 kilometers, they came upon a log jam across the water. The boat driver decided the jam was too wide to rev the engine and force the boat over at high speed as he had done with several other downed trees that morning. They could go no further.

The boat floated in silence for a few minutes when Ivan Batista, an experienced field guide hired for the expedition, spotted a black monkey leaping from branch to branch in a tall tree a couple hundred feet into the forest. With its thick hair and long fluffy tail, the saki monkey is easily distinguished from other monkeys that share these forests, even as a distant shadow.

.jpg)

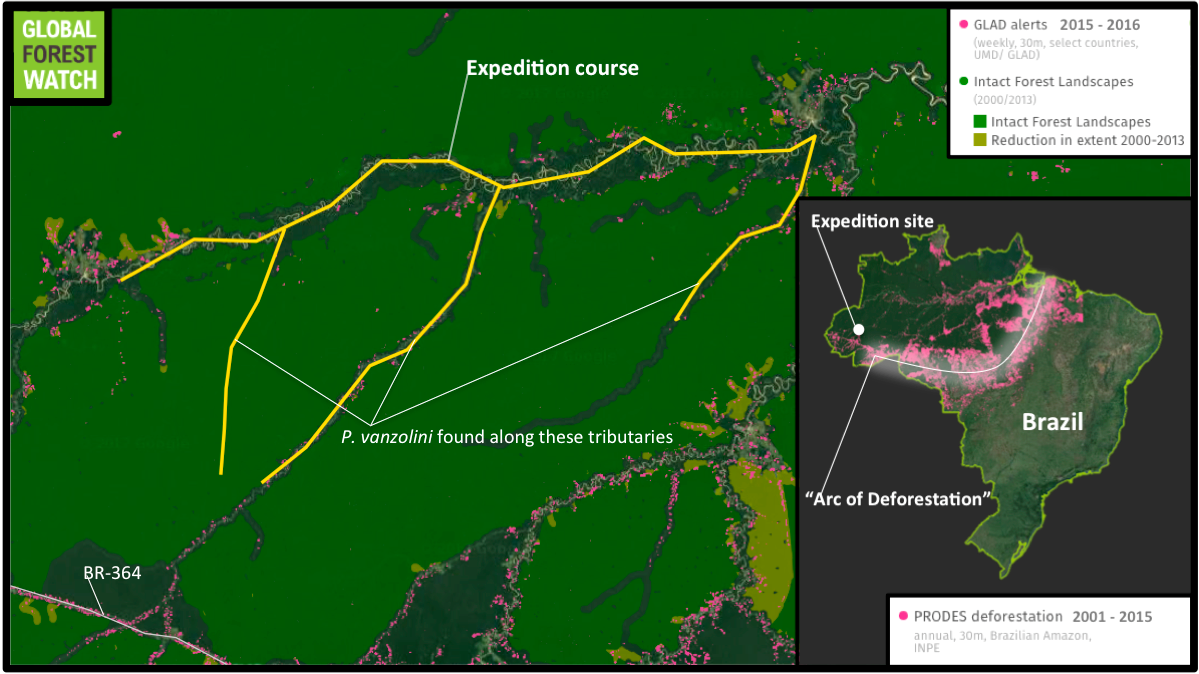

That was the first of what would be many encounters with the now rediscovered Vanzolini saki. Over the next three months, the expedition found the monkeys distributed along the entirety of the surveyed areas of the southern tributaries of the Juruá in Amazonas state and west from the Tarauacá River to the western side of the Liberdade River.

Threats from hunting and habitat loss

With the saki’s existence confirmed, the team turned to questions of their conservation status.

“Given what we’ve seen,” Marsh said, “if no further controls on hunting and forest clearing are put into place outside of what limited reserves currently exist, the saki’s conservation status may become critical.”

Hunting along the rivers in the Juruá watershed is having a major impact on primate populations, Marsh explained.

“Most of the large monkeys, which are a preferred food source [for local communities], have been hunted out of the forests along the Eiru and Liberdade Rivers,” she said.

Subsistence communities living along the rivers are allowed by law to hunt primates for food. Otherwise, since 1967 article 29 of Brazilian law 9.605/98 has prohibited hunting of wildlife. But, in remote areas like along the Juruá, environmental laws are hard to enforce. The expedition team often saw bushmeat being transported in canoes to sell in nearby cities, and city dwellers using the forests along the river to hunt and clear land for manioc and cattle.

Cattle ranching is the number one driver of deforestation in the Amazon, followed by subsistence agriculture and logging. Satellite data from the University of Maryland visualized on Global Forest Watch (GFW) show that overall most of the Vanzolini saki’s home range is still comprised of Intact Forest Landscapes, areas of primary forest big and undisturbed enough to retain their original levels of biodiversity. But GFW also shows tree cover loss creeping up from the south and outward from local cities along the Juruá River and Brazilian Highway 364.

The ringing sounds of chainsaws regularly accompanied field teams while in the forests. I joined a team on a dryland survey along the Tarauacá River. During a five-kilometer hike, we came across four active logging sites where local villagers were using chainsaws to cut felled trees into boards. We also heard two more active sites across the river. Several men carried long boards out on their shoulders and loaded them into their boat, which they would later take to markets in the city. Alejandra Duarte, a researcher from Mexico who collected data on resource use in each village where the expedition docked noted these loggers would receive between $3.75-$7.50 per 16-inch board, depending on the tree species.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

In this roadless area of the Amazon where rivers serve as the main transportation highways, wood for boats and homes is always in high demand. Logging for subsistence use is allowed by Brazilian law, except for certain protected species. Logging for sale, however, requires a permit from IBAMA, the Brazilian national environmental enforcement agency. “I can’t say that I saw any illegal logging in the study area,” Marsh said. Without specific knowledge of the laws or circumstances of the individual loggers, Marsh isn’t clear whether these activities were legal or not. The expedition didn’t encounter any large-scale commercial operations along the tributaries of the Juruá.

Roads bringing big changes

The biggest land changes in the past ten years have occurred in the state of Acre along BR-364, the only paved highway that connects the Vanzolini saki’s home range to the rest of Brazil. Paved in the early 1990s, this two-lane road cuts through Acre on its northern border with Amazonas and ends about 35 kilometers past Cruzeiro do Sul. For 30 years, the highway has been ushering in the “arc of deforestation” – a stretch of cleared forest that runs from Belem in eastern Brazil through the state of Rondônia. Satellite data from the University or Maryland show heavy tree cover loss spreading outward from BR-364; the UN Food and Agriculture Organization lists Rondônia as retaining less than half its primary forests. When I drove a two-hour stretch of this road outside of Rio Branco, only federally protected Brazil nut trees remained standing alone in pastures.

Dirt roads exit the highway in a fishbone pattern, extending clearing further into the surrounding forest mainly for cattle grazing. One of these roads is AM-329. While reportedly in very poor condition, it was built to facilitate transport from Eirunepé to the border of Acre.

Between eighty and ninety percent of Acre was covered in forest in 2015. But according to the National Institute for Space Research which tracks deforestation rates in Brazil by satellite, forest clearing increased 47 percent in the state in 2016. On Cruzeiro do Sul’s northern end, dirt roads are steering deforestation for cattle ranching from Acre up into Amazonas.

.jpg)

City dwellers in Eirunepé and Ipixuna are also clearing land for cattle and manioc farms. Large patches of newly slashed-and-burned forest are visible from a prop plane as it circles the airport to land in Eirunepé. Several hundred humped-back white cows stand in these fields.

Other small communities along the Juruá, Liberdade, Gregorio, Eiru, and Tarauacá Rivers are also chipping away at their surrounding forest. While each subsistence farm is relatively small, manioc requires clearing a new patch of forest each year.

The Liberdade River, closest to Cruzeiro do Sul, was the most affected river of the expedition study area. Communities of 50 or more families have been settled there for around 80 years, and large areas of land were converted for cattle ranching and manioc farms long ago. The Eiru River was the second-most affected. While the forest there was still decently intact, “it seemed like a free-for-all” in terms of hunting, fishing and manioc farming, said Marsh.

The Gregorio River, the middle river the expedition explored, was a different story. The river flows through an Extractive Reserve (RESEX), a type of sustainable-use protected area where people who live there can hunt and extract resources within a certain monthly quota.

“We heard less sound of chainsaws and came across fewer active logging sites on the Gregorio,” Marsh said. “I saw lots of standing big hardwoods, like cedars, that are nationally protected as well as many more types of mammals.”

Satellite data from the University of Maryland show significantly less forest clearing along the Gregorio than along the other rivers. While Duarte still found instances of illegal logging, hunting and wildlife trade in the RESEX, its status as a protected area does seem to be making a difference for conservation of the forest and animals compared to neighboring areas.

An uncertain future

Without evidence that hunting or forest clearing for manioc farms and cattle will slow down, the expedition researchers are concerned for the future of the newly rediscovered Vanolini saki monkey.

Current levels of impact have created a patchwork of human disturbance throughout the study area where monkeys still exist in pockets like lakes or distant dryland forest that are difficult to access. “If it just stayed at this level of impact right now,” Marsh said, “it’s not ideal for the conservation of Vanzolini populations, but at the end of the day it’s not killing the entire species because humans simply can’t get at them all.”

.jpg)

However, Marsh continued, “Whether hunting or taking out a tree, human presence causes an effect, particularly to mammals in the area, because we are all sensitive to each other.” In the case of selective logging, “when people take out trees that monkeys use for fruit or sleeping, that has a direct and personal impact on the primates.” But it’s the continued cumulative impact of hunting, logging, and other human pressures that concerns Marsh and her colleagues most.

Forests in Amazonas state are still mostly intact because the area is hard to get to and the forests flood for half the year. But, Marsh warns, “Every large-scale deforestation starts small at some point.” She and her team worry that if the technology for road building or timber extraction in flooded forest and the rugged terrain of dryland forest catches up, Amazonas could see an uptick in forest loss. Without further protections in the area, “Does this area turn into Rondônia? And if not, why not?” Marsh said.

With this expedition Houseboat Amazon created a baseline to track the health of the Juruá watershed. Over the long-term, Marsh and her team believe this data will be critical for improving management and conservation for the Vanzolini saki and other species in the region.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.