- Hunting for bushmeat impacts over 500 wild species in Africa, but is particularly harmful to great apes — gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos — whose small, endangered populations struggle to rebound from over-hunting. Along with other major stressors including habitat loss, trafficking and climate change.

- Bushmeat brings humans into close contact with wildlife, creating a prime path for the transmission of diseases like Ebola, as well as new emerging infectious diseases. Disease spread is especially worrisome between humans and closely related African great ape species.

- Bushmeat consumption today is driven by an upscale urban African market, by illegal logging that offers easy access to remote great ape habitat, plus impoverished rural hunters in need of cash livelihoods.

- If the bushmeat problem is to be solved, ineffective enforcement of hunting quotas and inadequate endangered species protections must be addressed. Cultural preferences for bushmeat must also change. Educational programs focused on bushmeat disease risk may be the best way to alter public perceptions.

Great apes should be humanity’s best bet for conservation — charismatic, intelligent, strikingly familiar, with big emoting eyes. It’s hard to think of creatures with whom the public empathizes more easily, or that are perceived as more worth saving, than our closest cousins.

And yet, we are failing them.

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are the most numerous of the African great apes, found across western and Central Africa, but their populations are suffering severe declines due to habitat loss and hunting. Eastern gorillas (Gorilla beringei) number fewer than 5,000 individuals in the wild and already have an extremely restricted range. And although Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) are more widely distributed, only 22 percent currently live within protected areas. Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are limited to small pockets of remaining habitat that have been wracked by civil war, lawlessness and violence.

Together with orangutans, these great apes represent our closest living relatives on Earth. All of them are Critically Endangered, except for bonobos, which are Endangered, according to the IUCN. And they all face a daunting onslaught of threats — ranging from habitat loss and trafficking, to climate change and war.

One of the most severe threats today is the thriving bushmeat trade. Bushmeat from the illegal hunting of wildlife — elephants, bats, antelope, monkeys, great apes, roughly 500 African species all together — is sold in markets across the continent, especially in economically well-off African cities, and even exported to Europe and elsewhere.

An old dietary habit threatens wildlife

Bushmeat has certainly existed as long as Homo sapiens sapiens, but traditionally was limited to small rural communities that relied upon the meat for subsistence.

Today, bushmeat has become big business, and it helps feed Africa’s booming human population. Estimates suggest that as much as 5 million tons of bushmeat is now being harvested across the Congo Basin alone, annually.

This growth in the bushmeat trade has been partly prompted by the logging industry — in particular, by the roads built to transport machinery and loggers in, and timber out. Across Africa, new roads are being carved through primary forest to reach new logging concessions. Those rough byways give hunters easy access to previously remote populations of wildlife, including chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas.

As a result, the bushmeat trade in Africa is “emptying the forests of wildlife faster than the timber companies can remove logs,” says Anthony Rose, director of The Bushmeat Project at California’s Biosynergy Institute. “Gorillas and other endangered species are slaughtered and stacked for transport along logging roads, to be sold in the billion dollar commercial bushmeat trade.”

Bushmeat and human disease

Humans share over 98 percent of our genome with chimpanzees and gorillas. This close genetic relationship is at the heart of a major problem facing Africa and the world today — disease transmission.

Humans are so similar to great apes that it takes almost no evolutionary effort for a harmful virus or bacterium to hop the species barrier — a leap that is a two-way street, with human-to-ape, and ape-to-human transmission both possible. The common cold, which is a minor inconvenience for a human, can kill a gorilla.

Disease transmission between wild animals and humans can occur whenever there is direct contact — this includes wildlife encounters with loggers, poachers and tourists, and especially with anyone who sells, buys, handles or eats bushmeat.

Scientists are particularly concerned about bushmeat-borne epidemics of new diseases. “Animals are a common source for the introduction of new infectious diseases into human populations,” says Michael Jarvis, virologist at the University of Plymouth. Some of the best known zoonotic diseases include HIV, the Bubonic Plague, Lassa fever, SARS, and most recently, Ebola. “Even malaria is believed to have been originally introduced into the human population from gorillas,” he says.

And this isn’t a minor risk: diseases transmitted from animals to humans represented 60 percent of all emerging infection disease events (EIDs) between 1940 and 2004.

Zoonotic diseases can originate in wildlife or livestock, but over 70 percent of zoonotic EIDs come from contact with wild animals. If an existing disease in wildlife evolves the ability to infect humans, our species is seriously vulnerable because we have no pre-existing immunity.

“The invasion of remaining wilderness in Africa is tapping a source of virulent new micro-organisms, bringing disease and death into urban human populations across the continent,” says Rose.

Lessons from history

One of the most devastating human epidemics in recent history was caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and evidence overwhelmingly points to an origin in great apes.

Chimpanzees can carry simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs), the wild ancestors of the most common human AIDS virus, HIV-1. Some time between 1910 and 1930, an SIV in a chimpanzee in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, made the leap to humans, although it would be another 60 years before the disease would reach pandemic stage in the United States and around the world.

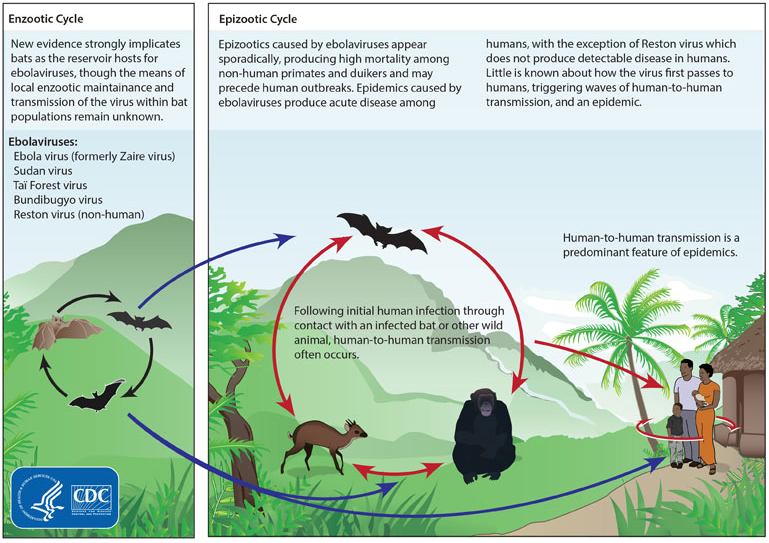

While SIVs required genetic changes to infiltrate the human immune system, some viruses are able to infect multiple primate species at the same time. One such virus is possibly the most feared human pathogen of all, at least to date — Ebola.

Ebola virus first emerged in 1976, with a few cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Sudan. Infecting humans, chimpanzees and gorillas seemingly indiscriminately, Ebola is fatal in 50 to 90 percent of cases, and has had a devastating impact on humans and wildlife across Central Africa.

Since 1976, it has re-erupted sporadically, with more than 20 outbreaks in humans and uncounted others in wild great ape populations. The human epidemic that began in West Africa in 2013 lasted more than two years and killed over 11,000 people. It also generated fear across the globe.

Many of these human epidemics also saw parallel outbreaks in apes, killing thousands of gorillas and chimpanzees in Central African rainforests — shrinking the populations of these primates within their last wild strongholds, and likely wiping out one third of chimpanzees and gorillas since 1990.

Searching for reservoirs

Zoonotic viruses and bacteria — with their ability to hide in remote regions and in a variety of unidentified species, and with their capability of jumping from one species to another — are extremely difficult to eradicate and safeguard against.

Ebola, for example, lives undetected in the years between outbreaks, hiding in a host that shows no symptoms, known as a “reservoir species.” While humans and apes show very severe symptoms if infected, silent carriers supply each new outbreak. Despite their searches, scientists have yet to conclusively identify the true reservoir.

The most likely Ebola reservoir candidates currently under investigation are bat species. The 2013-16 outbreak is now believed to have originated in a 2 year-old boy in Guinea, who most likely caught the virus from a fruit bat.

However, many human Ebola outbreaks have been sparked not directly by reservoir species, but by contact with infected apes. “This is not just happening once, but repeatedly over time,” Jarvis emphasizes. The “handling of Ebola-infected ape carcasses is known to be responsible for about 30 percent of all previous human Ebola virus outbreaks.”

Unknown, ignored bushmeat threats

As already mentioned, the risk of zoonotic disease is not limited to known pathogens; there is always the possibility that at any moment a new previously unknown disease will make the inter-species jump.

Just last year, a team led by Fabian Leendertz at the Robert Koch Institute in Germany, announced the discovery of a new Anthrax-like pathogen in wild animals across West and Central Africa.

Anthrax can be contracted by humans through contact with bacterial spores, or by consuming meat from infected animals. The bacterium infects chimpanzees and gorillas, as well as elephants and goats, and the Koch Institute team believes this variant could have already been the source of some anthrax outbreaks in humans.

Despite mounting evidence — ranging from HIV, to Ebola and Anthrax — local people’s attitudes towards the risks of bushmeat in Africa remain relaxed, says Marcus Rowcliffe, a Research Fellow at the Institute of Zoology in London who has studied the socioeconomic factors influencing bushmeat marketing trends. “Surveys have generally found that the vast majority of those involved in the [bushmeat] trade do not perceive disease as a significant risk.”

Seeking solutions

It isn’t clear yet whether the most recent Ebola outbreak may have changed perceptions in Africa towards these very real wildlife disease transmission risks. Experts say that educational programs that inform local people about the dangers of contact with wild animals could be a powerful tool for reducing bushmeat consumption — and could serve as a way to not only curb disease but to conserve wildlife by reducing demand for wild meat.

Another promising tool to reduce transmission of shared diseases like Ebola between humans and great apes is to vaccinate both. “A comprehensive vaccination program will be very important in protecting great apes from extinction,” says Jarvis.

The first vaccines against Ebola began being developed in the early 2000s, but remained stalled in the pre-clinical phases due to a lack of funding, which seemed logical considering the relatively small number of people impacted by the disease up to that time. Then came the 2013 epidemic, where more than 11,000 people were killed in West Africa.

By 2015 the Ebola vaccine had been rushed through phase III trials, where it proved 100 percent effective in humans. The good news: vaccines that act on Ebola in people can also be adapted for use with wildlife, including great apes, a goal that should be met quickly if we wish to save Africa’s primates from extinction.

So, how do you vaccinate a wild great ape?

While developing an effective Ebola vaccine is a crucial step for protecting humans, creating such a vaccine for great apes isn’t enough to safeguard our elusive primate cousins. “The problem for vaccinating wildlife, such as African apes, is not whether we have a functional vaccine, but rather how do we get access to the animals to vaccinate them?” says Jarvis.

Of course, some apes are easier to access than others. Many great apes have now been habituated to the presence of humans, whether by tourism or by ecological and behavioral research. These apes would be the easiest to vaccinate, and should be the first targets for disease protection because of their frequent contact with humans, which puts them at greatest infection risk.

Jarvis says that one way to get vaccines to less accessible wild animals is to slip it into their food. “Dropping vaccine-laden bait has proved extremely successful for control of rabies in wild carnivores in North America and Europe,” he says. However, this strategy is unlikely to work with African apes, which tend to be selective about the food they eat, and who live in hot, humid environments where bait decomposes quickly.

A promising option is a self-disseminating vaccine, which spreads from individual to individual just like the virus itself. Jarvis is part of a collaborative project to develop just such a system. The team is currently trialing a single-dose vaccine in macaque monkeys that could ultimately be developed as a spreadable great ape vaccine.

If successful, the approach would be a game-changer, he says, giving conservationists the “ability to control many emerging [zoonotic diseases], not just Ebola virus.” But he warns that the self-disseminating vaccine is still in the early stages of development, and may not be ready to apply to wild vaccination programs for another decade. That’s a long time to wait for Critically Endangered species.

The continuing bushmeat problem

Vaccines developed for known diseases only address one aspect of the primate contagion problem. As long as great apes are hunted as bushmeat, their populations will continue to decline, and there will be a risk of unexpected epidemics — brought on by an unknown virus or bacterium jumping from ape to human, causing an outbreak of a new infectious disease.

To protect our species and other species, we need to curb the trade in bushmeat, reducing it to sustainable levels, and quickly. That means much stronger great ape conservation measures as well as better protections for the roughly 500 other species regularly hunted as bushmeat across Africa. This is a goal not readily achievable by poor African countries, but it is in the interest of all nations to contribute financially to stopping new zoonotic epidemics before they start.

Better monitoring and enforcement of conservation laws and regulations would be a key step forward — in the wild and at every stage of the bushmeat supply chain.

But outlawing bushmeat won’t be enough. Understanding what motivates people to hunt and eat bushmeat is crucial if we are to tackle what has become not just an African problem, but a global phenomenon.

From subsistence to profit motive

For many living in rural communities, bushmeat remains a vital source of protein, but in urban areas across Africa it has become a commonly traded commodity.

“The main trend [in bushmeat consumption] has been a shift from subsistence-dominated to commercial-dominated use,” says Rowcliffe. This switch has been driven by growing numbers of wealthy urban bushmeat consumers, served by poor rural hunters, in conjunction with better transport links and well organized middlemen.

Bushmeat fits this model well, being a highly tradable commodity; relatively light and easy to move, and valuable. “Cities and towns across tropical Africa have thriving markets where illegal bushmeat is sold at two to six times the price of chicken or beef,” reports Rose.

Adding to entrepreneurial profitability is the fact that hunters can kill adult primates while capturing younger animals to be sold into wildlife trafficking networks — thus the bushmeat and illegal wildlife trade go hand in hand, along with drug and gun running.

Which is where war and civil unrest come into the picture. The civil war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the 1990s caused many people to flee the cities and move to rural areas, leading to a massive increase in bushmeat trade and shocking declines in wild populations. Militias hiding in the forest ate bushmeat, and sold it too, while participating in wildlife-, gun- and drug-trafficking, as well as supporting illegal logging and mining operations for conflict minerals such as coltan, used in consumer electronic devices.

“Conflict stimulates bushmeat trade and weakens conservation in general by breaking down existing protection and substituting a regime in which the military seek to extract rent from wildlife,” explains Rowcliffe.

Between 1990 and 2000 the rate of primary forest loss in DRC was double the post-war rate, bushmeat sales increased by as much as 23 percent and great ape numbers plummeted. This was particularly bad news for bonobos, whose entire range lies within the DRC.

Like other great apes, bonobos do not reproduce quickly, with a generation time of 25 years, making populations particularly vulnerable to hunting. Fewer than 20,000 are thought to remain in the wild today. They are shy and tend to avoid fragmented forests and areas of high human activity — rendering 72 percent of their historical range unusable. This puts the species in increasingly frequent contact with humans, where they risk being hunted as bushmeat or captured for the pet trade.

Rowcliffe notes that cultural norms continue driving the bushmeat problem: some local people have “a strong, persistent cultural attachment to bushmeat” over alternative sources of protein, and African people today get between 30 percent and 85 percent of their protein from bushmeat. However, according to one study, only rural consumers consistently prefer bushmeat, suggesting that urban markets may be more easily curtailed if the right financial incentives, legal deterrents, and/or disease risk education programs were put in place.

Alternatives to the bushmeat trade

If the bushmeat trade is to be curbed, governments and NGOs will also need to offer alternative livelihoods — including training and equipment — so poor hunters, and the middlemen who transport bushmeat, can support themselves with new jobs.

A 2011 report by the Convention on Biological Diversity suggested a number of viable alternatives to hunting bushmeat, including beekeeping, arts and crafts, fair trade crops and mini-livestock such as guinea pigs, frogs and even insects. The report suggests that breadwinners diversify their income sources rather than relying solely on a single trade. For example, the Anne Kent Taylor Fund has funded a project to retrain Maasai communities reliant on bushmeat to instead sell beaded jewelry and patrol the forests and plains for illegal poachers. With the profits from selling their crafts at local markets, the Maasai beaders have been able to build a grain mill and open their own shop, which they now run as additional sources of income.

Rowcliffe believes that bushmeat harvesting can become sustainable in Africa, “in theory, but it will require profound societal changes. There are many productive and resilient species in the bushmeat trade that can support sustainable hunting,” he says, but ongoing demand for bushmeat and a lack of effective government support for hunting restrictions are major barriers to this transformation.

The worry is that none of these changes will come soon enough to save the great apes, whose population numbers continue to fall. As our closest cousins stagger under a pummeling attack from deforestation, habitat loss, trafficking, war and climate change, will bushmeat and human-transmitted disease be the final two straws that break the back of Africa’s great apes?

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.