- Giorgos Mountrakis and Sheng Yang of the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry analyzed satellite-derived land cover data in order to look at geographic patterns of forest loss in the continental US during the 1990s.

- The average distance from any point in the U.S. to the nearest forest increased some 14 percent just between the years 1990 and 2000 — a difference of about one-third of a mile.

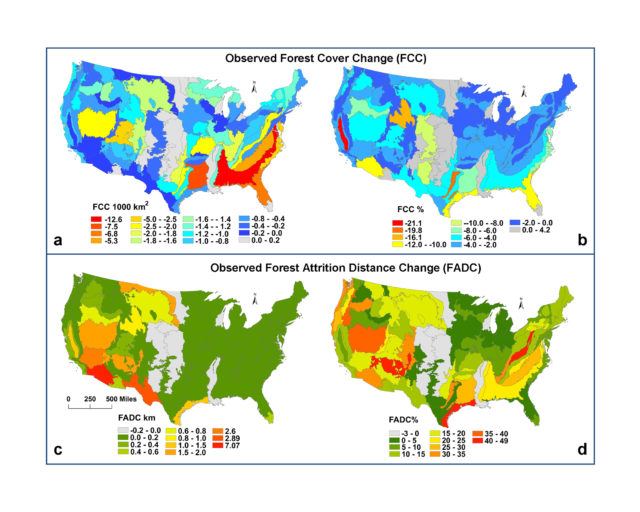

- They found that total forest cover loss across the country during that decade was close to 35,000 square miles (a little over 90,000 square kilometers), a decline of about 2.96 percent, or roughly an area the size of the state of Maine.

Americans living in the continental United States looking to get out into nature have a longer drive ahead of them than they would have had in the early 20th Century. According to a new study, the average distance from any point in the U.S. to the nearest forest increased some 14 percent just between the years 1990 and 2000 — a difference of about one-third of a mile.

That may not represent a major barrier to heading out on a nature hike, but it can make a real difference for wildlife and the overall health of ecosystems.

Giorgos Mountrakis, an associate professor at the State University of New York’s (SUNY) College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, NY, and Sheng Yang, a graduate student at SUNY, analyzed satellite-derived land cover data in order to look at geographic patterns of forest loss in the continental US during the 1990s. They found that total forest cover loss across the country during that decade was close to 35,000 square miles (a little over 90,000 square kilometers), a decline of about 2.96 percent, or roughly an area the size of the state of Maine.

“While we focused on forests, the implications of our results go beyond forestry,” Mountrakis said in a statement. The researchers detailed their findings in a study published in the journal PLOS ONE last month.

The geographic pattern of the forest cover loss discovered by Mountrakis and Yang was perhaps their most surprising finding — as well as the most concerning, they said. The researchers determined that there were considerably higher levels of forest attrition (the complete removal of forest patches, as opposed to forest fragmentation, which is when smaller areas within a larger forest are cleared) in rural areas of the U.S. than in urban areas.

“The public perceives the urbanized and private lands as more vulnerable,” said Mountrakis, “but that’s not what our study showed. Rural areas are at a higher risk of losing these forested patches.”

Even the loss of small forest patches can have a severe impact on wildlife and the healthy functioning of ecosystems, Mountrakis added, using bird migration as an example of an “ecoservice” supplied by forests that is compromised when forest patches are destroyed. “You can think of the forests as little islands that the birds are hopping from one to the next,” he said.

The removal of key forest patches that connect larger forested areas can make it much more difficult for birds and other animals to move around, in other words — and they can’t simply hop in their car to overcome the increasing distance to the next forest. “There are numerous impacts of forest attrition including complete habitat losses, severe decline of population sizes and species richness, and shifts of local and regional environmental conditions,” Mountrakis and Yang write in the study.

Mountrakis added that forest attrition can have serious impacts “for local climate, for biodiversity, for soil erosion. This is the major driver — we can link the loss of the isolated patches to all these environmental degradations.”

All of which means these findings could have serious implications for conservation efforts. And Yang said that while the focus is often on conserving urban forests, “we may need to start paying more attention — let’s say for biodiversity reasons — in rural rather than urban areas. Because the urban forests tend to receive much more attention, they are better protected.”

Few studies have examined the geographic pattern changes in forests other than fragmentation, Mountrakis and Yang note in the study, despite what such research can tell us about the biggest threats to forests. They found that forest attrition is higher in the western half of the U.S. than in the east, especially on lands owned by the federal or local government, pointing to the need for better public land management.

“Forest losses are dominant in gap areas in western ecoregions leading to severe forest attritions, whereas in eastern regions forest losses appear in the interior or near the forest edge thus causing lower attrition,” the authors write in the study. They attribute this difference to a variety of factors, including lower tree density and higher terrain heterogeneity in the west, as well as the fact that forest fires and insects are more prevalent in the west while harvesting in managed forests is a more significant contributor to forest loss in the east.

“[I]f you are in the western U.S. or you are in a rural area or you are in land owned by a public entity, it could be federal, state or local, your distance to the forest is increasing much faster than the other areas,” Yang said. “The forests are getting farther away from you. Distances to nearest forest are also increasing much faster in less forested landscapes. This indicates that the most spatially isolated — and therefore important — forests are the ones under the most pressure,” said Yang.

Mountrakis and Yang argue that estimations of forest attrition can aid in conservation planning in a number of ways. It’s easier to project changes in climatic conditions like temperature and precipitation once forest attrition is estimated, for instance. “Estimating these climatic changes can lead to better understanding of potential impacts on genetic diversity of various species,” they write.

“In addition, in order to promote carbon sequestration in forests and in turn mitigate climate changes, biomass and carbon changes from forest attrition need to be carefully evaluated to determine most profitable mitigation measures, for example reforestation, because forest attrition often causes irreversible carbon losses compared to other geographic patterns of forest loss.”

CITATION

- Yang, S., & Mountrakis, G. (2017). Forest dynamics in the US indicate disproportionate attrition in western forests, rural areas and public lands. PloS one, 12(2), e0171383. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171383

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.