- As people settle closer to remaining natural areas, livestock predation by lions and other wild carnivores causes financial loss to often poor herders and farmers.

- Disruptive light systems, invented independently by herders trying reduce nighttime guarding of animals, emulate the movements of a night watchman to dissuade lions, foxes, and other predators from approach penned livestock.

- Users of Lion Lights, invented by 11-year-old Richard Turere, and similar light systems report very high success in deterring would-be predators and can play a role as part of a human-wildlife conflict reduction toolkit.

Human-lion conflict is widespread across the African continent (Bauer et al. 2010). Most lion predation occurs on livestock penned in overnight corrals (bomas) and leads to widespread lion persecution.

Cattle, goats and sheep kept near lion territories are vulnerable to predation when they are trapped in a boma with no human guardian present. Lions seek out weak spots in the enclosure, such as a gate or corner, kill the livestock and drag it out of the boma. Their sight and smell may also intimidate the livestock, triggering a bull to break through the fence and initiating a stampede that puts the entire herd at risk (Mbithi et al. 2012).

Retaliatory killing by herders, combined with habitat loss and poaching, has devastated lion populations across Africa; the total population has declined by 43% since 1993, to fewer than 20,000 today.

To prevent lion killings by aggravated farmers, conservation organizations have attempted to install “predator-proof” livestock enclosures—made with chain link, woven branch, or living Commiphora tree fences—and recommended that farmers stay vigilant, or at least employ guard dogs as early warning systems (Woodroffe et al. 2007).

Predator-proof bomas have been very effective in protecting livestock but can cost up to $2000USD each, precluding use by most individual herdsmen to address a problem that spans the continent.

Necessity and long nights inspired invention

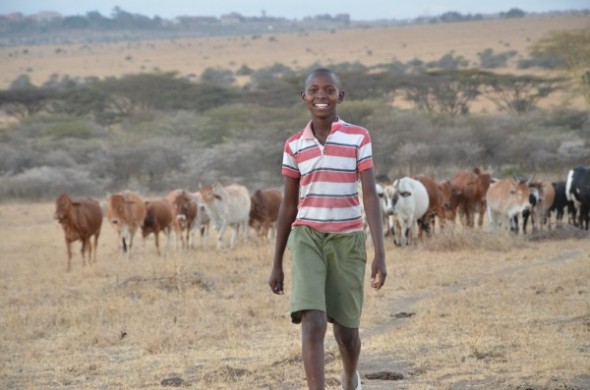

In 2010, 11 year-old Maasai Richard Turere from Kenya, wanted to develop a low-cost method of protecting his father’s cattle. Inspiration struck when Turere realized lions avoided raiding his farm’s cowshed when he patrolled the perimeter with a flashlight.

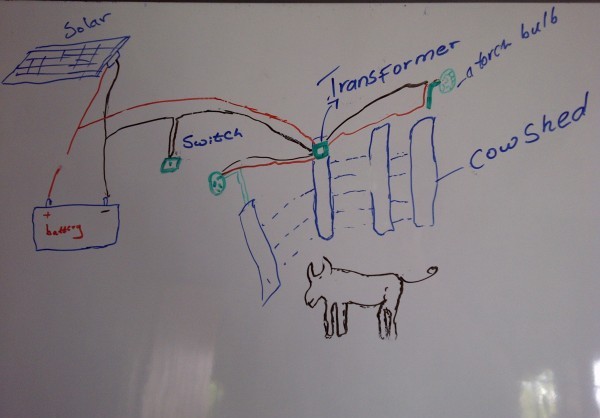

An inventor at heart who wanted to limit his all-night patrolling, the young man built a system of flickering strobe lights using a solar-powered battery, a motorcycle indicator (the turn signal switch), and pieces of broken flashlights. Turere’s entire system (in the diagram below) cost him about $10USD, as his only purchase was the solar panel.

He attached the LED lights to fence poles facing outwards, leaving the interior of the corral cloaked in darkness. The flickering motorcycle indicator produces the illusion of a human guard patrolling the enclosure with a flashlight. The flickering effect may help prevent potential predators’ habituation to consistent lights, which previous predator damage control studies showed.

Turere was widely celebrated for his “Lion Lights” system, which has been adapted and implemented across Kenya. Sandy Simpson of Green Rural African Development modified the original design and introduced “Lion Lights” in Zimbabwe and Zambia to address human-wildlife conflict involving a number of predatory species, including lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, and even crop-raiding elephants.

Turere received broad recognition for his “Lion Lights” system, which has been adapted and implemented across Kenya. Sandy Simpson of Green Rural African Development modified the original design and introduced Lion Lights in Zimbabwe and Zambia to address human-wildlife conflict involving a number of predatory species, including lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas and even crop-raiding elephants.

More recently, The Wildlife Foundation has trained electricians in Kenya to maintain and repair the light systems, which are solar-powered. Kalasingha, a Nairobi-based NGO, recently installed Lion Lights along the boundary of Nairobi National Park to help reduce lion attacks on nearby livestock and people. The African Lion and Environmental Research Trust (ALERT) project, inspired by Turere’s invention and Simpson’s additions, has since deployed NiteGuard, a similar system created by a U.S. farmer, to sites around Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park.

While formal data are not readily available, lights projects overall report a very high success to date. Turere confirms in his 2013 TED talk that the installations at his own home and village in Kenya have prevented new lion attacks. More recently, Jackie Abell, of the lion ALERT project, told Wildtech that their light systems “have been in operation for six months, with a 100% success rate. To date we have had no reports of attacks at night on kraals in the Matetsi safari area of Zimbabwe that have the lights.”

Farmers in other countries have created similar light systems for temperate-zone environments. In addition to NiteGuard from North America, Australian Ian Whalan devised the “Foxlight,” which flashes at different times and colors and in different directions, and have helped him reduce incidents of foxes killing his livestock. He has since begun testing the light system on native carnivores in Africa and Asia.

It is still likely that solving human-carnivore conflict will require a suite of management tools, including lights, predator-proof corrals and improved livestock husbandry. Herders will probably need to remain vigilant over their livestock and not rely entirely on a passive system that emulates the movements of a night watchman.

If you have used the Lion Lights or other disruptive lights technology, please tell the community about your experience!

Others will benefit from knowing when and where these systems work best, as there is little recent information about them online. Are these lights so effective that they are widely accepted, or are challenges and setbacks simply not reported? Help us close the information gap!

Here is Turere’s 2013 TED talk on the development of the Lion Lights system:

Citations

Bangs, E. and Shivik, J. 2001. Managing wolf conflict with livestock in the Northwestern United States. Carnivore Damage Prevention News 3: 2-5.

Bauer, H., de Iongh, H., and Sogbohossou, E. 2010. Assessment and mitigation of human-lion conflict in West and Central Africa. Mammalia 74: 363-367.

Mbithi, M., Parmisa, N., Tuleto, J., & Sorimpan, D. 2012. Kitengela, Isinya and Kipeto boma predator-proofing. FoNNaP Community Lion Project. Retrived February 23, 2015 from here.

Woodroffe, R., Frank, L., Lindsey, P., ole Ranah, S., and Romañach, S. 2007. Livestock husbandry as a tool for carnivore conservation in Africa’s community rangelands: a case–control study. Vertebrate Conservation and Biology 5: 419-434.