- Researchers and wildlife managers are testing new techniques to monitor elephants’ movements and maintain their habitat

- Reserve managers benefit from combining data from ranger and animal tracking tags, surveillance, and environmental data

- Unmanned aircraft systems could assist with censusing and keeping track of cattle, to help reduce overgrazing of fragile arid ecosystems

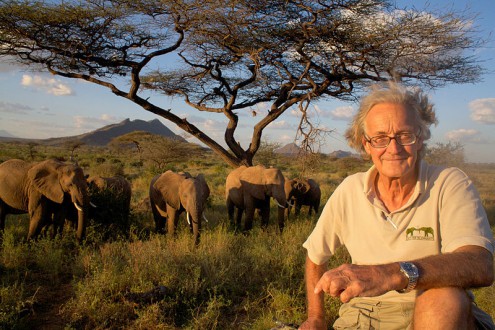

Sitting at a conference table in Washington DC, Iain Douglas-Hamilton taps at an iPhone clad in a bright red case. Douglas-Hamilton, 73, is one of the world’s leading experts on African elephants, having studied the largest land animal for more than half a century. Through Save the Elephants, a research and conservancy organization he founded in 1993, Douglas-Hamilton works as a tireless advocate for elephants—fundraising, lecturing around the world and combating the resurgent trade in elephant tusks.

Save the Elephants runs and funds more than fifty research and conservation projects, from installing beehive fences around farmers’ fields to studying the ivory trade in China. But one of their most productive and technologically intensive endeavors involves GPS tracking of elephants in Kenya.

“Here,” Douglas-Hamilton says, turning his phone toward those across the table. “Here we have the elephants we’re currently tracking.”

On the screen glows a satellite image of East Africa overlaid with a series of thin colored lines: turquoise and yellow and red marks that run like twisted threads over the land. With a stroke of his fingers, Douglas-Hamilton zooms in on the map, revealing a few of the paths in greater detail. And at the end of each thread stands a tiny, color-coordinated image of an elephant.

Here’s a snapshot of a week of elephant tracking data from northern Kenya earlier this year, during which 13 elephants traveled down to the Ewaso Nyiro River during the day and into surrounding hills at night.

The system—the result of years of effort and innovation—combines information gathered from reliable GPS collars, a sophisticated database that manages the elephants’ location data and a user-friendly visualization tool conveniently integrated with the Google Earth platform.

WildTech spoke with Iain Douglas-Hamilton about his work, the technology he uses and the challenges he faces in conserving elephants and their habitat.

An Interview with Iain Douglas-Hamilton

Tell us more about your elephant tracking system.

We developed this system because we realized it was very useful for the park managers to be able to carry this information into the field. But now we’re getting near real-time monitoring. We’re getting location fixes made on the hour, which you can download onto your iPad. You can then take this with you into the field and you can go out of connection, but you can get the last fix and fly straight into where the elephant was last seen.

This is part of a wider effort called the Domain Awareness System. We started tracking elephants for security in Meru National Park in 2003 with the warden. Those were old fashioned collars. The warden happened to have a pilot at his disposal, so every morning the pilot would go out with his twin antennae pointing out off the wings and home in on each elephant, which was great, but now we can do the same thing via satellite, so you know exactly where you’re going when you set out.

Of course you’ve got to search around and find exactly where the elephant is. So we’re talking at the moment with Vulcan Inc. and others about how to get this even more precise. We’d like to be told the position of the elephant when we get within range; we don’t want the location to the last hour, we want it to the last 10 seconds.

We shared this technology with Lewa Conservancy, who probably have the most advanced anti-poaching operation in Africa, and we were able to arrange for them to put distribution data on a very large television screen in their office. They love it. It’s been the most rewarding thing to work with people who were so keen to take this up. And now, they’ve added to that — they add systems on an ad-hoc basis. The next idea is to integrate the system into the Domain Awareness System.

The other place we’ve deployed is Virunga National Park. We’re not sure yet whether one screen is a good idea and should have everything on it, but that’s probably the direction we’re going. You’ll have positions of your ranger forces (which are given to you from the radios they work with that generate a GPS signal every time they’re used. They could equally easily carry a tracking device which speaks to satellite and could give their position quite frequently). So all of that could be on one screen, and then you add other information, such as where the poachers are.

I think the level of detail we want is going to be determined very much by the level of operational experience—we don’t want clutter. And the people who need to drive this are the law enforcement people on the ground who will say “I like this; I don’t like that.”

What’s been the most challenging aspect of your work?

Finding the poachers.

There are many, many challenges. One big challenge that we personally have experienced is when you have nighttime contact, and you know an elephant’s been poached. You’ve heard the gunshots, and you send out a patrol, and they can hear the tusks being chopped — chopped off the elephants. Now, if they close in they’re going to get shot at, that’s for sure. So what is challenging is to maintain contact with those poachers until dawn, when you can spot them and intercept them.

And of course we’ve played around with ideas of using night sensing and tracking and whatnot, and the subject of drones always comes up. Or having a helicopter with a pilot who’s got thermal goggles. Now the question is, how do you maintain contact? And I think the Domain Awareness System will be very helpful to automate keeping track of friendly forces. You’ve got a helicopter and some cars and some rangers on foot, and the idea then of using the Domain Awareness System to coordinate is a great one.

There’s a compromise between having the right information and having too much clutter, and that can only be achieved on the ground, in practice. My view is that most of the testing can be done in the field or in simulations. I love the idea of simulations, where you have band of guys who play poachers and a band of guys who play rangers playing war games, testing it out.

All I can tell you already there’s a very, very high level of training in and around the Northern Rangeland Trust. They’ve already got rangers’ posts and scouts in different conservancies who feed in information. If they see or hear something, they will tell the Ops Room, which produces a daily digest of information. They have a daily SitRep, they call it—a situation report—where they report all the things that have happened in the past 24 hours, and they’ll issue an alert.

We interact with them a lot because we’re right out there in the front lines. We’ve been through crises, we’ve encountered poachers in the area, we’ve frequently heard gunshots.

Technology should just be an adjunct, a help. It should not be driving. The people on the ground should be able to take technology and adapt it. They’ve taken our stuff, and they’ve put it straight to use, and they love it.

Can you see this system replicating anywhere else?

Absolutely. Doing so is the next question. For us, this system is great, and we’d like to deploy it in different places, in Tsavo [National Park], for example. We’d also want to see smartphones using the tracking system deployed in reserves across the region.

How has the technology changed?

I think it was in the mid 90’s we, and we did a thing called Ellie Telly. We put a collar on an elephant, poor thing, it probably weighed about 20 kilos because it had a television camera behind a plate, and had windscreen wipers, and it carried around probably four gallons of water supply. It would spray every time the elephant splashed mud on itself. And it worked, it worked for 20 days. We got a continuous record of this elephant’s movements.

We’d like to bring traditional collars up a notch. One technology we still lack is a drop-off mechanism so that the collar will fall off after a specific period of time. But it would also need a low-level listening capacity so that if need be you could tell it “Drop off now.”

How well are your various HEC reduction strategies working, and where? Which techniques might be most easily scalable to whole villages or regions?

The Elephants & Bees project is going well; we’ve just partnered with the Disney Conservation Fund to produce our first project video. The fences successfully repel elephants 80 percent of the time at the Sagalla test site [near Tsavo East National Park], and we have been supporting the establishment of beehive fence projects by new partners in both Africa and Asia [here’s one from South Africa]. Of course these fences cannot solve all HEC problems, and other solutions are needed in other environments. Our HEC toolbox to provide these alternatives is progressing.

Geofences will only be a proper solution when we have a workable way of tracking elephants without collars, I believe. Tracking with collars continues to provide good information on elephant ranges to help avoid conflict in the first place.

What are some additional uses for technology that would benefit your work?

I would like to fly drones over bomas [corrals] and count cattle. Nobody’s counting cattle properly in Kenya, but they are the driving ecological force for all the wildlife in our area. We’ve got a real problem with overgrazing. We’ve got a problem with wildlife encroachment into the park and into reserves, and it’s really a very bad situation right now.

I’ve done some work with this in the past, we did a little program in 1994, we were engaged to do a national review of cattle counting techniques by the Ministry of Agriculture.

If you could effectively count cattle in a boma, you could then take it to the next stage. The next stage would be to get a drone or series of drones and predetermine the place where the bomas are located in a place where you want to know how many cattle there are. You make a flight plan that goes from boma to boma to boma. The reason why it’s important is this: in the region where we work, all the livestock goes into the boma at night. It means that if you can census the boma, you can actually get full count of the cattle. Maybe. What we do is normally we wait until they come out of the boma and we count them from there, but it’s so much more difficult in some ways.

The final endpoint would be to find means of doing cheap, repeat censuses either from a satellite or from a light aircraft or from a drone or from a combination of all three. And if we were using thermal imaging we could do it just before dawn where you get the maximal difference between a warm blooded mammal and the background. And I think what we’ll find is that you will just see a blob, which will mean “yes, that boma’s occupied by livestock.” But the potential is that you could do corrections that would tell you what that blob means. … The ultimate aim would be to get a very cheap way of censusing livestock around the year. You could score which bomas are occupied at which times of year. You could do this once or twice a month, and if you do it over time, it could be a game-changer. You could take it one stage further like they do in the fisheries, and you could actually start spotting remotely livestock making incursions into the reserve.

Because the livestock at the moment are one of the biggest problems. It’s a problem for the people who live there because they depend totally on the livestock, and it’s a problem for the rest of the people who depend on the wildlife, because at the moment wildlife have been negatively impacted by the livestock in a major way.

Over the years that I’ve been there, I’ve never seen the reserve looking as bad as it is now. Not even during the drought of 2009. But we believe we can influence government policy simply by providing very accurate information.