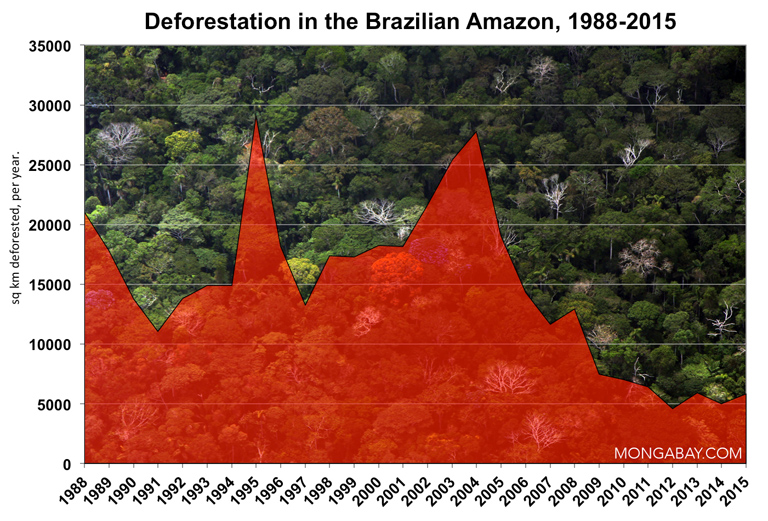

- While deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has fallen sharply over the past decade, a larger share of forest loss is now being driven by small-scale actors.

- The reason for the shifts appear to be related to Brazil’s system for monitoring deforestation. Large-scale clearing is more easily detected by the satellite system.

- Study conducted by Climate Policy Initiative and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro.

While deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has fallen sharply over the past decade, a larger share of forest loss is now being driven by actors who are more difficult to control, putting up a new challenge in the battle to limit destruction of Earth’s largest rainforest, reports a new study published by Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio).

The study, which confirms earlier research concluding that the recent decline in deforestation has mostly been the result of reductions in clearing by large-scale landholders, looked specifically at trends in Pará and Mato Grosso, states which together account for roughly two-thirds of forest loss in the “legal Amazon”, an area Brazil officially recognizes as the Amazon biome. However the findings suggest the reality is more complex than conventionally assumed, with smallholder clearing accounting for a significantly larger share of overall forest loss in Pará compared with Mato Grosso.

“At the beginning of the 2000s, smallholders in Mato Grosso tended to clear their property in medium- and large-scale tracts of land. While smallholder’s share of deforestation remained constant over the 2000s, the share of small-scale clearings increased in the state. This is because clearings of medium- and large-scale tracts fell inside medium and large properties,” stated CPI on its website.

“At the beginning of the 2000s, smallholders in Pará were much more engaged in small-scale clearings than in Mato Grosso. Deforestation on small properties remained relatively more persistent in Pará throughout the early 2010s. In addition, the share of small-scale clearing in overall state deforestation increased sharply into the late 2000s, especially when compared to Mato Grosso.”

The reason for the shifts appear to be related to Brazil’s system for monitoring deforestation. Large-scale clearing is more easily detected by the satellite system, which an earlier CPI study concluded was responsible for more than three-fifths of the observed drop in deforestation since 2004. Clearings under 25 hectares are usually missed by the alert system used for on-the-ground law enforcement.

“Researchers suspect the change in clearing size from medium and large-scale tracts to smaller tracts may be mainly due to the effectiveness of the remote-enforcement program that thwarted clearings larger than 25 hectares. When this type of illegal activity was more easily detected by the monitoring system, and, thus, more effectively contained, property holders in Mato Grosso shifted their deforestation activities to smaller tracts of land to escape detection.”

In contrast, because proportionally more deforestation in Pará has been driven by smallholders historically, they had less need to actually curb their practices.

“Pará landholders were more likely to elude the remote monitoring system because they were much less visible to law-enforcers,” said CPI. “This suggests that conservation policies may have been more effective in curbing deforestation in Mato Grosso than Pará.”

The conclusions are consistent with the messaging Brazilian authorities have been espousing in recent months, attributing blame for an apparent rise in deforestation to “illegal deforesters”. Others have pointed to other issues, including Brazil’s weakening economy and currency as well as the 2012 revision of the country’s Forest Code, which relaxed regulations on forest clearance on private lands. All of these developments post-date the study period, which runs from 2004-2012.

Nonetheless, the findings still have important policy implications.

First, say the researchers, Brazil needs develop and implement a better remote-sensing based monitoring system that detects small-scale clearing. Given recent advances in satellite and drone technology, combined with use of artificial intelligence and predicative models for forecasting where deforestation is likely to occur, that isn’t as tall an order as it would have been even just five years ago.

Second, Brazil must craft actions that more effectively target small-scale deforestation. But regional differences mean that a one-size-fits-all strategy is likely to fail, so policymakers need to consider specific local conditions.

And third, Brazil shouldn’t let down its guard with medium- and large-scale clearing given the substantial role those actors have had historically in chopping down the Amazon.

“It is clear that Brazil’s efforts to curb deforestation are working,” said study co-author Juliano Assunção, Director of CPI’s Brazil operations and professor at the Department of Economics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, in a statement. “Our study shows, though, that there are still challenges. We need to step up forest protection strategies on smaller tracts of land.”

CITATION: Juliano Assunção and Clarissa Gandour. Strengthening Brazil’s Forest Protection in a Changing Landscape. Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio). Published: August 2015.