A female California sea lion bearing a satellite tag tends to her pup. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

A female California sea lion bearing a satellite tag tends to her pup. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

For decades, many global conservation efforts have focused on protecting declining populations of large predators at the top of the food chain, and there are numerous successful stories of recovery. From an ecosystem perspective, however, the reemergence of large predators has also created new conservation challenges, according to a recent paper.

In the U.S., legal protections — in particular the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) — have promoted the recovery of many marine and terrestrial species, including California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) along the west coast and gray wolves (Canis lupus) and grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) in the Greater Yellowstone region.

In the paper, published in the journal Conservation Letters, scientists explored the effects of these recovering predator populations on their home ecosystems, outlining three major unintended conflicts that have resulted.

First, they say, increased numbers of predators have led to competition with humans for the same prey. Second, the protected predators sometimes target protected prey species. Third, competition can arise between multiple protected predators for the same prey. All three pose conundrums for wildlife managers that often don’t have a clear resolution.

A California sea lion rookery in the Channel Islands off the California coast. The species, while still facing serious challenges, has rebounded from around 10,000 animals in the 1950s to around 355,000 today. Photo credit: NOAA Fisheries/Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

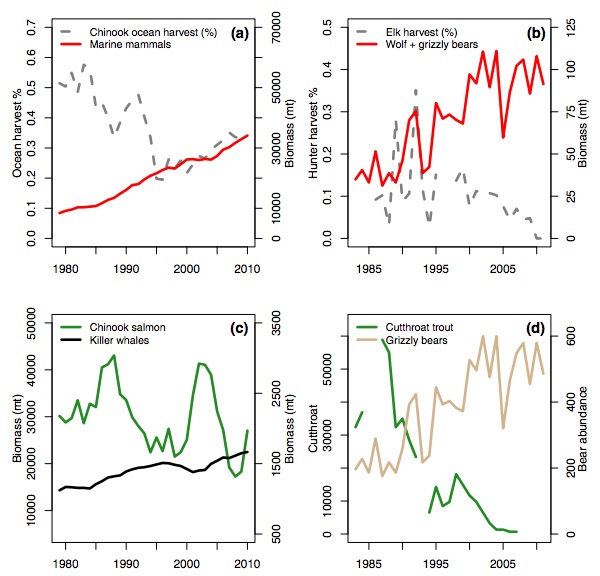

According to the paper, in the Pacific Northwest the comeback of California sea lions and killer whales, as well as Pacific harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), all protected under the MMPA, has increased the animals’ competition with humans for fish. Furthermore, all three predators feed on the ESA-protected Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), whose populations are declining. And competition for fish among the predators could adversely affect them all.

“These conflicts between humans and marine mammals for shared resources have been occurring for 1000s of years around the world — what makes the present conflicts interesting is that we’re trying to resolve them while also recognizing the protection of these predator species under the MMPA,” Eric Ward, a fisheries biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and co-author of the paper, told mongabay.com.

Similarly, in the Greater Yellowstone region gray wolves and grizzly bears, both protected under the ESA, now compete with recreational hunters, as well as with each other, for elk (Cervus elaphus). The resurgence of both predator species has placed increased pressure on elk populations, which are declining in number, according to the paper.

A bull elk rests along a stream in northern Yellowstone National Park. Elk numbers in the area have declined as wolves and grizzly bears have rebounded. Photo credit: Kristin Marshall.

The authors note that there are plenty of other "multispecies conservation conflicts" besides the ones they highlight. As examples, they point to rebounding seal populations that are targeting dwindling cod on the east coast of North America, protected seals and sea lions that are eating threatened steelhead runs in Puget Sound, and a threatened fox that eats an endangered shrike in California, where protected golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) feed on both species.

The ESA and MMPA have what the authors call "safety valves" that allow for the killing of protected species under certain circumstances to decrease these kinds of conflicts. But these can be controversial and the outcome uncertain. For instance, they write, "Culling [seals and sea lions] is legally feasible, but may not be socially acceptable."

To resolve these three kinds of conflicts when predators rebound, the authors recommend improving monitoring programs and modeling systems to better understand predator-prey interactions, and ultimately developing multi-species recovery plans for ecologically linked animals. As the authors state in the paper, there are no conservation management guidelines for preferentially protecting one species over another when they have similar levels of protection.

A killer whale eats a salmon near the San Juan Islands off the coast of Washington state. Chinook salmon, which are protected under the Endangered Species Act, are the favored food for the area’s Southern Resident killer whales, another protected species. Photo credit: Candice Emmons, NOAA Fisheries/Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

“We just don’t have many examples of how to implement these multi-species recovery plans, so in some ways solutions to these conservation challenges will involve venturing into uncharted waters,” Ward told mongabay.com.

Both the ESA and MMPA mainly focus on the protection of single species, but also emphasize the importance of maintaining healthy ecosystems and protecting critical habitats.

“The intention of the ESA (and MMPA) is ultimately to protect ecosystems, even though both laws are typically implemented on a species by species basis,” Kristin Marshall, a post-doctoral researcher at NOAA Fisheries and the lead author of the paper, told mongabay.com.

“It’s clear that reintroducing or recovering predators benefits ecosystems, however it is also increasingly evident that there are associated costs,” said Marshall. “Understanding and communicating potential costs and the benefits will likely lead to better science, management, and policy outcomes.”

(a): Time series of Chinook commercial fishing harvest and biomass of marine mammals (pinnipeds, resident killer whales) in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. (b): Time series of predator biomass and elk harvest rates on the northern range elk herd of Yellowstone National Park. (c): Time series of ocean abundance of Chinook salmon and their killer whale predators in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. (d): Time series of Yellowstone cutthroat trout, a declining but unprotected species, at Clear Creek in Yellowstone National Park, and grizzly bear abundance in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Credit: Marshall, K., et al. (2015).

Citations:

- Marshall, K., Ward, E., Stier, A., Kelly, R. (2015): Conservation challenges of predator recovery. Conservation Letters. CONL-14-0299.R2.

}}