A laundry list of dangers threaten Amazonia’s few remaining uncontacted indigenous communities. Colonists and industry workers often grab tribal land for mining, logging, drug trafficking, or hydrocarbon extraction, which damage the groups’ environment and bring them into conflict with armed settlers. Careless encroachment by outsiders can also bring diseases to which uncontacted groups have no immunity.

Locating and keeping tabs on settlements is an important step in protecting communities from the advances of colonists and even government-sanctioned development. But this has often entailed direct contact or aerial surveys with low-flying planes, which cost researchers thousands of dollars per flight and cause undue stress to people being surveyed. A number of aerial images show villagers shooting arrows at planes or fleeing into the forest.

In the past few years, however, scientists have begun to explore using high-resolution satellite images to gather data on the location, population, and configuration of uncontacted communities. Surveys using these images can cost as little as US $10 per square kilometer and they provide higher-quality, more systematic data than aerial surveys. A study in the journal Royal Society Open Science uses images purchased from high-resolution image databases and the mapping software ArcGIS to locate and measure villages, gardens, and houses in five uncontacted communities near the Brazil-Peru border.

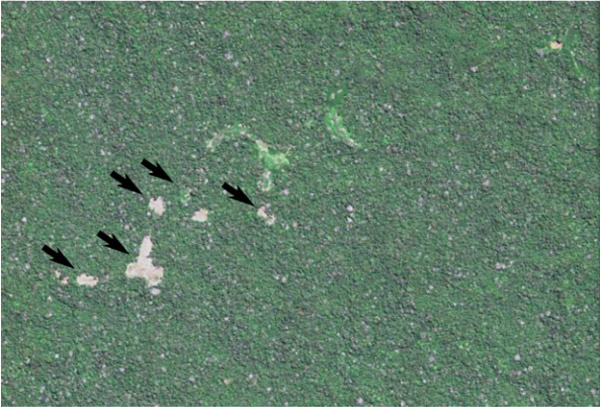

Western portion of site H that was monitored during the study. From 2012 to 2013 this site showed an increase in slash-and-burn fields that are designated by arrows, as well as an expansion of two large cleared areas in the center. These changes total 16 ha cleared in 14 months.

The study used tips from news stories and Brazil’s indigenous agency, Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI) to get a sense of where the communities were located before zeroing in on them and eventually purchasing high-resolution images for specific areas.

The researchers were able to learn quite a lot about the communities by analyzing the satellite images. For instance, one village was visible in 2006 satellite images, but appeared abandoned and overgrown in 2012 images. A 2014 overflight showed the community had moved to a nearby location. And using population estimates from FUNAI, the team calculated that the communities surveyed had about two square meters of indoor space and .11 hectares of land for each inhabitant, making their living space an order of magnitude denser than that of most contacted tribes.

“As indigenous people acculturate, the density goes down quite dramatically,” Robert Walker, an anthropologist at the University of Missouri who led the study, told mongabay.com. “We want to find and measure more isolated villages and compare them to contacted villages… and see how [both] move and change over time.”

Satellite image of clearing and houses for a section of site F2 that was monitored during the study.

The approach could also be used to monitor the effect of external threats like logging on indigenous communities’ populations and movements. Satellite images have the potential to significantly augment FUNAI’s existing strategies to protect uncontacted groups, like overflights and law-enforcement stations at remote forest outposts, the researchers write. “We could be much more vigilant of monitoring encroaching external threats, and at a lower cost, using a remote surveillance program that would alert a mobile team to help stop specific invasions into protected indigenous lands,” said Walker.

Satellite monitoring did not identify individuals or faces and it involved spatial analysis rather than direct interaction, alleviating concerns about consent and privacy, Walker said. However, he was careful not to reveal the exact locations of the communities in his paper for fear that doing so “might facilitate some people causing harm to these isolated villages,” he said.

According to the study, the ultimate goal of this work is the security of uncontacted people and specifically “a longitudinal surveillance program across Amazonia that can facilitate informed decisions by policy-makers to increase protection of isolated populations.”

Uncontacted indigenous tribe in the Brazilian state of Acre. Photo by: Gleilson Miranda / Governo do Acre via Wikimedia Commons.

Uncontacted indigenous tribe in the Brazilian state of Acre. Photo by: Gleilson Miranda / Governo do Acre via Wikimedia Commons.

Citations:

- Walker RS, Hamilton MJ, Groth AA. Remote sensing and conservation of isolated indigenous villages in Amazonia. R. Soc. Open Sci. 1:140246. 2014.