OTHER REPORTING BY DAVID HILL

Brazilian firm’s mega-dam plans in Peru spark major social conflict

Peru is proposing a huge hydroelectric dam in the Amazon that, if built, will be one of the most powerful on Earth, do significant harm to the environment, and flood the homes of thousands of people.

The proposed mega-dam would be constructed at the Pongo de Manseriche, a spectacular gorge on the free flowing Marañón River, the main source of the Amazon River.

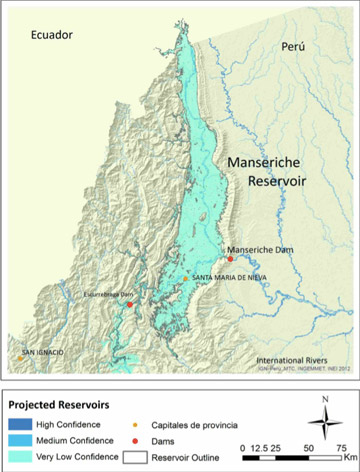

The dam’s reservoir would flood as much as 5,470 square kilometers (2,111 square miles) and drown the town of Santa Maria de Nieva in the Amazonas department of northern Peru, along with some of neighboring Ecuador, according to an estimate made in a 2014 report by the U.S.-based NGO International Rivers (IR). That estimate was made with admittedly “very low confidence” because of a lack of current available information from Peru’s government.

Santa Maria de Nieva, a small town at the confluence of the Nieva and Marañón rivers that would be flooded by a dam at the Pongo de Manseriche, according to estimates by International Rivers. Photo credit: David Hill

Santa Maria de Nieva, a small town at the confluence of the Nieva and Marañón rivers that would be flooded by a dam at the Pongo de Manseriche, according to estimates by International Rivers. Photo credit: David Hill

Building momentum for the Manseriche dam

Proposals to build a dam at Manseriche have knocked about since at least the 1970s, but current interest is strong, with Peru’s energy sector and president Ollanta Humala touting it as an important upcoming project.

In 2007, Manseriche was slated by the Energy Ministry (MEM) as one of 15 proposed dams that could export electricity to Brazil. Then in 2011, a law declared a Manseriche dam to be in Peru’s “national interest,” along with 19 other proposed dams on the Marañón’s main trunk.

Two years later in September 2013, president Humala cited Manseriche as a means of supplying energy to gold and copper mining companies. Speaking at a mining industry conference in Arequipa in southern Peru, Humala declared that: “In order to operate they [the companies] need energy, and for that the construction of at least five hydroelectric power stations generating more than 10,000 megawatts is envisioned.” A map depicting Manseriche and four other proposed dams was included in his presentation.

The Pongo de Rentema, the site of one of three proposed dams that would drown Awajun ancestral territory. Photo credit: David Hill

In December 2014, the Manseriche dam was presented as a potential project during the United Nations climate change summit held in Lima, according to Evaristo Nugkuag Ikanan, from the indigenous Awajun people, who would be most impacted by the dam.

“They present these proposals in order to obtain funds for these kinds of projects,” explained Nugkuag Ikanan, who works for the Condorcanqui municipality in Nieva.

One local Amazonas government official told Mongabay.com that plans for the Manseriche dam may have progressed even further. He claimed that William Collazos Collazos, a MEM representative, made a presentation at a recent internal meeting, revealing that a company has been granted a concession for the dam, which would permit initial work to begin. Neither Collazos Collazos nor MEM responded to requests for confirmation.

Might the IDB fund it?

In 2014, scientists from the U.S.-based Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), financed by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), conducted research immediately up- and downriver from the Pongo de Manseriche, according to the IDB itself, WCS Peru director Mariana Montoya, and Awajuns living in the region.

The proposed Manseriche dam would flood a 5,470 square kilometer (2,111 square mile) area, including the town of Santa Maria de Nieva and part of neighboring Ecuador, according to an International Rivers estimate. Map credit: International Rivers |

The WCS research is part of a $750,000 IDB “technical cooperation” (TC) project aiming to assess and model the “value of ecosystem services (e.g. spawning habitats and nurseries critical for fish biodiversity and local fisheries), and their likely changes under different hydropower development scenarios” on the Marañón River, the IDB wrote in an emailed statement to Mongabay.com.

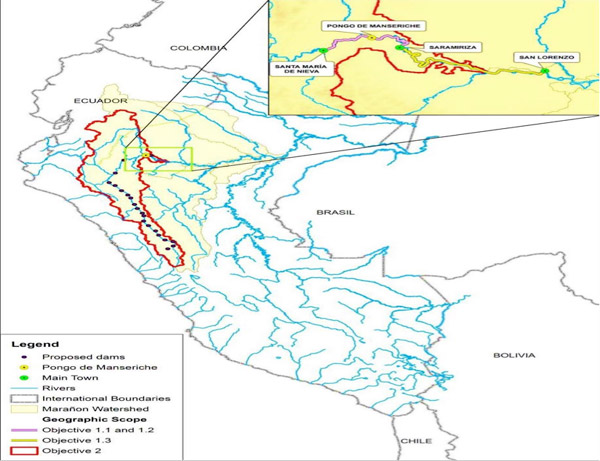

The TC project is ultimately “expected to leverage funds for future Bank operations… as well as generate opportunities for future green investments in sustainable hydropower, fisheries and natural or green infrastructure,” according to the IDB. As a map sent to Mongabay.com makes clear, the Pongo de Manseriche is one of the main geographical focuses of this research.

However, the IDB informed Mongabay.com that “at present, [it] is not considering any proposed financings of hydroelectric projects in the Marañon River basin, including Pongo de Manseriche.” WCS Peru director Mariana Montoya emailed that: “our work is not connected to any proposal to build the dam.”

Serious impacts, serious opposition

If Manseriche is built, thousands of indigenous Awajun and Wampis men, women and children would lose their homes and see their land and crops, upon which they depend for survival, flooded.

The Awajuns and Wampis live primarily along the Santiago, Cenepa, Marañon, Nieva, Potro, Apaga and Morona rivers. Nearly the entire Santiago valley, and much of the Nieva and Cenepa valleys, would be flooded by the dam’s reservoir, according to IR’s 2014 report.

Almost every Awajun and Wampis interviewed by Mongabay.com was opposed to, or seriously concerned about, the proposed Manseriche dam. It would, they said, have devastating impacts on migratory fish stocks, flood their homes and crops, and force them from lands to which they have strong cultural and spiritual attachment.

Very large tracts of agriculturally productive land, like these ricefields just upriver from the Pongo de Rentema, would be drowned by Peru’s mega-dams on the Marañón River. Photo credit: David Hill

“For us the Pongo de Manseriche is very important for fishing,” said Zebelio Kayap Jempekit, president of the Cenepa Frontier Communities Organization (ODECOFROC) representing Awajun communities along the Cenepa River. “Many fish arrive there from Iquitos [a city downriver]. They spend a lot of time there.”

Wrays Perez Ramirez, a Wampis man and president of the Permanent Commission of the Awajun and Wampis Peoples (CPPAW), told Mongabay.com that forcing indigenous peoples to leave their homes and land is “genocide” and “ethnocide.”

“If they build the dam, the fish are no longer going to migrate upriver,” he said. “We live from these resources, from these forests… [and] they’re going to destroy [it all].”

Violent conflict?

Some Awajuns feel the proposed dam could lead to violent conflict and a second “Baguazo,” the name given to the initially peaceful protest by thousands of Awajuns and Wampis near the town of Bagua in 2009. Events turned violent there after security forces opened fire on the protesters, leading to more than 200 people being injured and over 30 killed, including more than 20 policemen.

“If they try to dam Manseriche and send in the army, we would be prepared to give our lives in defense of our forest,” Edgardo Aushuqui Taqui told Mongabay.com. He is the former vice-president of the Aguaruna Domingush Federation (FAD), which represents Awajun communities immediately upriver from the Pongo, which would be flooded.

Crosses marking the deceased after peaceful protests turned violent near Bagua, Peru in 2009. Some Awajuns say there could be conflict if plans to dam and flood their territories move forward. Photo credit: David Hill

“This will be a second Bagua for us,” Aushuqui Taqui said. “I’ve never heard anyone say the dam would be a good thing. Wherever I go, [people] always say the same thing: if [the government and companies] try and go ahead with the dam, they won’t allow it. There is no community you could go to where anyone will say they want the dam. Not one Awajun is going to say we want it.”

Cesar Sanchium Kuja, secretary for the Chipe Kusu community on the Cenepa River, said the proposed dam could lead to “very serious” armed conflict.

“We’re never going to allow this dam to be built,” he told Mongabay.com. “We’re not going to accept it. This is the only land we have. We don’t have more land. Where would we live? If the government wants to build a dam, it should do it in Lima, with the Rimac [River]. We’re going to annul [this proposal].”

“We can’t let this happen”

Many Awajuns and Wampis interviewed feel similarly to Sanchium Kuja and said they will not permit the Manseriche dam to be built.

“We can’t let this happen,” said Roberto Kugkumas Bakuach, FAD’s president. “We won’t allow anyone to do this, not the state nor any company.”

“If they build the dam, it’ll flood everything,” said Raquel Yampis Petsayit, president of the Indigenous Awajun Women’s Association. “We’ll all die. Our leaders have rejected it.”

The town of Bagua, together with neighboring Bagua Grande, would be flooded by the proposed dam at the Pongo de Rentema, according to estimates by International Rivers. Photo credit: David Hill

In previous years, some Awajuns have come together to issue statements denouncing the mega-dam, according to Madolfo Perez Chumpi, president of the Organization for the Economic Development of Awajun Communities on the Marañón (ODECAM), which represents communities between the Pongo de Manseriche and Nieva, which would be inundated.

“We live along the banks of the river,” said Perez Chumpi. “Where are we going to plant our manioc? Our plantains? Our maize? Where will we find the fish that swim upriver? This is scary for us, for our children. For the government and the companies, this is development, but it’s not [development] for us. We don’t accept the plan to build a dam at the Pongo de Manseriche.”

No consultation, little information

A common complaint of the Awajuns and Wampis interviewed for this article involves the government’s failure to consult with them about the proposed dam, as required by Peruvian and international law. They also resent the lack of available information. Although the 2011 law declaring the Manseriche dam to be in Peru’s “national interest” also states that MEM “will co-ordinate with native communities,” local people say that no official has ever visited Awajun or Wampis territory to discuss it.

“There has never been a meeting with the apus [leaders],” said Octavio Shacaime, from the Northern Peruvian Amazon’s Regional Organization for Indigenous Peoples (ORPIAN-P), based in Bagua.

Despite these government failures, there are a few details — often conflicting – that are available. The 2011 law states that the Manseriche dam would be capable of generating 4,500 megawatts (MW), making it over 5 times more powerful than Peru’s largest existing dam. However, MEM’s 2007 report on exports to Brazil, a 2012 MEM presentation, and the 2013 map shown by president Humala to the mining conference all assert that the dam would generate up to 7,550 MW. That would make Manseriche one of the top 10 most powerful dams in the world, according to Gregory Tracz, from the International Hydropower Association, along with Peter Bosshard, IR’s interim executive director.

The possible precise location of the dam and an extremely vague indication of the area that would be flooded have also been made public. One alternative suggested in MEM’s 2007 report states that the reservoir would not “extend into Ecuadorian territory. A 1976 study puts the height of the dam itself at 126 meters (413 feet).

Map for a project funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) researching the potential impacts of dams on the Marañón River. The Pongo de Manseriche is one of the main focus areas. Map credit: IDB

Some Awajuns and Wampis appear to have a rough idea of the area to be flooded — knowledge gleaned from IR’s report and other sources. “The priest [now deceased] said that if they dam the Marañón — especially at the Pongo de Manseriche — it will flood the entire population along the Santiago, and [the town of] Nieva would disappear,” said Amanda Longinote Diaz, president of the Virgin of Fatima Indigenous Women Entrepreneurs Association.

Where the Awajuns and Wampis would be expected to move if the dam is built, or how they would be compensated, is another unknown. No one interviewed said they had any communication from the government regarding this issue.

“Where are we going to live? Where would we go?” asked Longinote Diaz. “Bagua is not a reality for us. Jaen [another nearby town] is not a reality for us. We live from the river, from the forest.”

MEM did not respond to questions for this article.

How serious is the threat?

Some people are skeptical as to whether the Manseriche dam can ever be built because it would be so controversial and the social and environmental impacts so devastating.

IR acknowledges in its 2014 report that at 4,500 MW, “the immensity of this project, as currently planned, makes it nonviable.” The impacts of a 7,550 MW dam would be even greater.

“I don’t think they’ll ever do it,” Peruvian engineer Jose Serra Vega told Mongabay.com. “It’s an old idea. It’s an idea they’ve had forever.”

More than just Manseriche

The dam at Manseriche is not the only one that would drown parts of Awajun and Wampis territory. One of the other 19 proposed dams declared in the “national interest” by the 2011 law is planned for the Pongo de Escurrebraga (1,800 MW), upriver from Manseriche. IR’s 2014 report estimated, again with “very low confidence,” that this dam would flood 875 square kilometers (337 square miles).

Still another dam declared to be in the “national interest” by the 2011 law is slated for the Pongo de Rentema (1,525 MW), upriver from Escurrebraga.

The spectacular entrance to the Pongo de Rentema, the site of one of more than 20 dams proposed for the main trunk of the Marañón River. Photo credit: David Hill

Rentema and Manseriche are two of the five dams president Humala cited at the 2013 mining conference as providing energy to gold and copper mining companies. According to IR’s 2014 estimate — also made with “very low confidence” — Rentema would flood 874 square kilometers (337 square miles) and submerge the towns of Bagua and Bagua Grande.

“Our position is ‘no’ to the three dams downriver from Rentema,” said ORPIAN-P’s Octavio Shacaime, who calls the Pongo de Manseriche the Awajun’s “spiritual centre” and compares it to Mecca, The Vatican, St. Peters and Rome. “Every culture has its sacred space. We’ll never allow this to happen. We’ll never consent to this idea.”

}}