Chukotkan dancers. Subsistence hunting will be increasingly difficult for the Inuit who depend on marine mammals in the Arctic to provide them with food and materials for clothing. Photo by: Edward Struzik.

For most of us, the Arctic is not at the front of our minds. We view it as cold, stark, and, most importantly, distant. Yet, even in an age of vast ecological upheaval, one could argue that no biome in the world is changing so rapidly or so irrevocably. Two hundred plus years of burning fossil fuels has warmed up the top of our planet more quickly than anywhere else. The result? Sea ice is shrinking, glaciers are vanishing, southern species are invading, storms are worsening, floods are creeping further inland, and indigenous people and other locals are struggling to adapt. Governments are responding largely with calls for more exploitation. With easier access to the north, many are calling for increased oil and gas production, mining, fishing, and shipping lanes through once frozen seas.

Unlike most of us, journalist Ed Struzik has witnessed many of these changes first hand for more than three decades. His new book Future Arctic: Field Notes from a World on the Edge provides a broad, comprehensive, and fair-minded look at not only the upheaval in the Arctic, but what should be done about it. Struzik examines everything from the tar sands industry to the plight of polar bears and caribou to the political wrangling over the resources of the north.

In a February interview with mongabay.com, Struzik talks about his non-traditional route to journalism, how governments should manage the high north, and if anything can be done about climatic changes at the top of the world.

An Interview with Ed Struzik

Mongabay: What’s your background?

|

Ed Struzik: I began my career as a naturalist working for the Canadian national park service in Kluane National Park in the Yukon Territory in the early 1980s. It was a wonderful contract position. I had hoped it would morph into a full time job, and it might have. But I became disenchanted when the government came up with a management plan that included building a tramway up a mountainside, deploying shuttle buses to a glacier, and boating people into remote inland lakes. They wanted to transform the pristine wilderness of Kluane into a Yosemite or Banff of the North. I quit and wrote about this insanity in a magazine—the first article I ever wrote. The plan was eventually shelved. I’m sure that my story had little to do with it, but shortly after, I got word from one senior park official that my safety could not be guaranteed if I returned to the park.

It was the beginning of a new career that has since taken me to the far corners of the circumpolar world, and back to Kluane several times. It also got me a year-long fellowship at Harvard and MIT where I was able to study under the likes of E.O. Wilson, Stephen J. Gould, Richard Lewontin and one terrific geologist by the name of Sam Bowring.

Mongabay: What first drew you to the Arctic?

Ed Struzik: Family that lived in the Yukon and the prospects of climbing, hiking, kayaking and canoeing there. I was, and still am, crazy for outdoor adventure, and there is no better place to explore than the Arctic.

Mongabay: What continues to draw you?

In the 1990s, scientists such as Ian Stirling and Andrew Derocher predicted the demise of polar bears at the southern edge of their range as sea ice retreated. Photo by: Edward Struzik.

Ed Struzik: Once I started writing about the Arctic, scientists began inviting me to field camps, icebreaker journeys, aerial surveys and other field trips. I just couldn’t resist being involved in the capture and tagging of polar bears, beluga whales, narwhal, barren-ground grizzlies, peregrine falcons and other Arctic animals. Nor could I turn down lower profile permafrost scientists whose idea of a good time was to simultaneously slam shut field books to see who could kill the most blood-sucking mosquitoes. More often than I expected, it was these lower profile scientists who ended up being the most interesting.

The invitations keep coming and they include trips with Inuit hunters. I cherish those invitations the most. That said, I’m not as fond of caribou and bison surveys, such as the one I did in the spring of 2014. There’s nothing worse than being cramped in the back seat of a small bush plane for hours on end, looking out the window for small brown dots on the tundra while the plane is bobbing and weaving. That said, I’d probably go if I were to be invited again.

CLIMATE UPENDING

Mongabay: How does the Arctic’s deep past allow us to look differently at changes happening before our eyes?

Canadian scientist John England stands by a tree trunk at Ballast Brook on the northwest cost of Banks Island where trees such as redwood grew as high as 22 meters and were as thick as 60 millimeters in diameter between 2 and 10 million years ago. Photo by: Edward Struzik.

Ed Struzik: If the past tells us anything, it tells us that when change happens in the Arctic, it happens very fast and often catastrophically. Before Europeans arrived on the scene, natural forces that are always at play drove climatic change. Those forces are still at a play, but they are being accelerated by greenhouse gas emissions. We are now moving into uncharted territory.

Mongabay: Is there anything that can be done to stop the rapid warming in the Arctic or is this a foregone conclusion by this point?

Ed Struzik: Even if we slowed greenhouse gas emissions now, it would be decades, possibly centuries, before we would see a dramatic ebbing in the warming that is taking place. But that’s no reason to stop trying. Many of the Arctic animals—specialists such as the beluga whale, the narwhal and the polar bear—species that are most threatened by a rapidly warming world may still be around in much smaller numbers in the next century or two. A halt or reversal in the warming could prevent their extinction.

Mongabay: You’ve seen the impacts of climate change in the place that is changing the fastest worldwide. What do you say to people who still deny global warming?

Ed Struzik: It depends on the denier. To those who are genuinely confused by what they read or hear in the media, I describe to them what I’ve seen first hand over the past 35 years—polar bears and beluga that are getting thinner in some places, southern animals like red fox, coyote, and even mountain lions that are moving north, and increasingly powerful summer storms that are sending surges of seawater 30 kilometers inland in some low-lying places of the western Arctic.

To those whose beliefs are driven more by ideology than science, I tell them that I’ve lived and worked in the Arctic for the past 35 years and that I’ve seen first hand the changes that have taken place.

Mongabay: How are animal communities changing in the Arctic? We hear a lot about polar bears. What’s the real story?

Arctic icebreaker. Funding for climate change science in Arctic Canada has suffered in recent years as a result of the government’s assault on environmental issues. Photo by: Edward Struzik. |

Ed Struzik: The life cycles of ice and snow dependent critters such as Arctic cod, beluga whales, narwhal, polar bears, and even lemmings are being affected most by the warming that is causing sea ice to retreat and make subnivean lairs unstable. At the same time, we are seeing southern animals such as killer whales, Pacific salmon, and red fox moving into, and potentially displacing, Arctic animals such as the beluga, Arctic char, and Arctic fox. Some of these animals are carrying diseases for which Arctic animals have no immunity.

As scientist Andrew Derocher constantly tells me, the real story about polar bears is a complex one because there are 19 sub-populations that are faring differently depending on where they live. The sorry part to this explanation is that polar bear scientists don’t have enough funding to get the data needed to determine whether eight of those populations are increasing, stable or declining. The good news is that three of the populations that were declining are currently listed as stable. The bad news is that three populations—those in Baffin Bay, Kane Basin and the southern Beaufort Sea—are declining.

The good news, however, may not be as good as some people believe. Chukchi Sea bears, for example, appear to be doing well in comparison to southern Beaufort Sea bears that are not doing well. But as biologist Stephen Amstrup recently noted, primary productivity in the Chukchi Sea is up to 10 times greater than it is in the adjacent Beaufort Sea. That means there may be more prey available. And although both the Chukchi and Beaufort experienced major sea ice losses during the latest study period (2008-2011), the Beaufort Sea had twice as many ice-free days as the Chukchi. The thinning of some of the thick, multi-year sea ice in the Chukchi, says Amstrup, may be providing better access to seals, at least temporarily.

EXPLOITATION

Mongabay: Your new book covers the Canadian oil sands, but you were exploring this story decades before this became a global issue. Did you see all this coming back in the 1980s. Could it have been prevented?

Ed Struzik: I first saw it coming in the early 1980s when I was the environment reporter for a newspaper in Alberta where most of the oil sands operations are located. Talking to oil sands and environmental scientists back then, it became clear to me, and to most of the scientists, that there was no way you could rip up and dig out muskeg that was millions of years in the making and have any hope of sowing it back up and returning it to anything like it once was.

Three saw whet owl chicks. There is no single reason that many birds that migrate to or live year-round in the Arctic are showing signs of stress, but it’s clear that climate change is contributing to the problem on a variety of levels. Photo by: Edward Struzik.

A clearer picture emerged in 1984 when I spent several weeks in the Peace-Athabasca Delta, visiting native people whose lives were profoundly affected by a spill at the Suncor oil sands plant, which was located upstream. The pollution tainted the fish so badly that the modest commercial fishery they worked so hard to establish had to be shut down. It has never recovered. To compensate for their losses, the government gave them a total of $45,000 to divide up among 62 of them. Some got as little as $12. Suncor, on the other hand, was fined just $8,000 after a long protracted trial that cost the government millions. The remainder of the pollution charges against Suncor were subsequently stayed.

I realized then this juggernaut was not going to be stopped. The government was going to sacrifice whatever was needed to keep the oil sands going.

Mongabay: How might water be the ultimate definer of the tar sands industry?

Ed Struzik: The oil sands require a tremendous amount of water—about 3.1 barrels of water per barrel of oil produced by mining operations; 0.4 barrels for in situ operations. In 2010, the industry produced 1.6 billion barrels of crude per day. Some of this water is recycled. But most it comes from the Athabasca River, whose waters end up in the Arctic Ocean. Even people in the industry acknowledge that they may face a water crisis in the future if oil sands expansion proceeds.

So where is the water going to come from? Most scientists believe that there will be less water flowing north along the Athabasca as snowpack and glaciers retreat in the Rocky Mountains. If this happens, the Alberta government will be forced to stop giving water to the oil sands for free as it does now. The prospect of water shortages and water pricing is already forcing the industry to develop new and more expensive ways of extracting oil from the sand. The price of water and the cost of extraction may eventually force some companies out of business, especially if oil prices stay low.

Mongabay: How do you view efforts for offshore drilling in the Arctic?

This Canadian base camp is located off the coast of Borden Island in the High Arctic. Canada and the five coastal Arctic nations are redrawing the map of the polar world, with claims to territory that currently belong to one. Photo by: Edward Struzik.

Ed Struzik: I think there should be a moratorium on offshore oil and gas development until the biological hotspots are mapped and protected. I also think that offshore oil and gas development should not proceed until engineers find a way of effectively separating oil from ice. If there was a blowout in the Arctic and the oil got under the ice, powerful currents could carry the oil a long way into areas where whales, walrus, polar bears, sea birds, and fish thrive. Experiments in the 1970s showed that when polar bears are oiled, they will lick it off, unaware that it would poison them.

Mongabay: Given the high risks, worsening climate change, and the industry’s history in the region do you see any chance of governments deciding to leave the Arctic Oceans untapped?

Ed Struzik: President Obama’s recent decision to permanently remove 3.9-million hectares of ecologically important Arctic marine waters from oil and gas leasing is really a positive development. It may not set the bar high enough, but it will prove that the world won’t end because we didn’t drill in these areas. Hopefully, other countries will follow suit. I think they will, if there is enough public pressure.

Mongabay: How could the current low oil prices impact the Arctic scramble for resources?

Ed Struzik: I think that low oil prices will slow development in the Arctic to a crawl. Frontier oil and gas is very expensive to exploit and until prices rise back to the $80 a barrel level or more, I think we’ll continue to see little interest in the region. If Exxon or Shell or someone else taps into a Prudhoe Bay-like reserve, however, all bets are off.

RESEARCH AND ATTENTION

Mongabay: What is the state of Arctic research and what is needed?

Ed Struzik: Support for Arctic science is good in Norway and Sweden, terrific in Germany, which is a non-Arctic country, and not bad in Greenland, which is supported by Denmark. U.S. scientists struggle for funding, but they are kings compared to the beggars that most Canadian scientists are. Just consider the state of polar bear science in Canada. Two-thirds of the world’s polar bears live in Canada. But the Canadian government employs just one scientist to work full-time on the species. The territory of Nunavut employs another.

Mongabay: Environmental scientists have been muzzled in Canada, but what’s the state of environmental journalism there?

Ed Struzik:

In 2008, I was runner-up to a team from the New York Times for the $75,000 Grantham Prize for environmental journalism. The newspaper series— wrote focused on climate change and the Arctic. A few weeks—after I went to Washington to attend the award ceremonies, an editor at the paper I reported to took me aside and told me to stop writing about climate change. He insisted that it was a fad that had run its course. Fortunately for me, the editor of the paper backed me up. This is one reason I no longer work for newspapers.

Caribou may be more resilient to climate change than many scientists believe. What they need most is space, especially on their calving grounds. Photo by: Edward Struzik.

There has never been much in the way of job security for environmental journalists in Canada. But it can’t get any worse than it is now. First rate journalists such as Andrew Nikiforuk (winner of the Rachel Carson Medal and a Grantham Prize finalist as well) no longer see their names in the mainstream media.

Alternative media such as The Tyee out of Vancouver are trying to fill the void. But it’s an uphill battle. Just today, Canada’s national newspaper ran a front page story in which the head of the company behind the Keystone Pipeline reduced the debate to send oil sands along a pipeline through the U.S. as a “little bickering,” that has to be stopped “so that institutions that manage the public good can get on with doing their job.” No one – not an aboriginal leader, an economist, an NGO—is given a chance to challenge what he had to say in the article.

Mongabay: Overall, do you think the Arctic, and ongoing changes, gets enough attention in the global media?

Ed Struzik:

It never has and probably never will so long as the Arctic is out of sight and out of mind. Things, however, are likely to improve as it becomes increasingly clear that the Arctic matters to the rest of the world.

But it’s a a huge investment sending a journalist to the Arctic—a round trip to Resolute from New York, Washington or Toronto can cost $4,000 or more. Accommodations are unbelievably expensive (I usually hunker down in a tent and bring my own food) and the weather is unpredictable (I have been trapped by bad weather that lasted for several days).

The New York Times, The Guardian, and a handful of other mainstream papers are doing a reasonably good job of covering Arctic issues, but they rarely send anyone there. And so is Yale Environment 360, an on-line magazine I contribute to on a regular basis. http://e360.yale.edu

FUTURE

Mongabay:

Given that the Arctic is so far away from most people’s everyday experience, why should they care what happens up north?

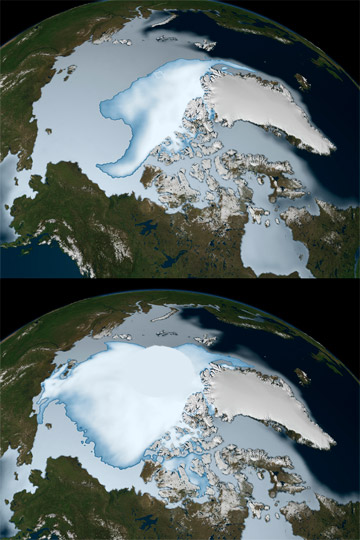

The image shows sea ice coverage in 1980 (bottom) and 2012 (top), as observed by passive microwave sensors on NASA’s Nimbus-7 satellite and by the Special Sensor Microwave Imager/Sounder (SSMIS) from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP). Multi-year ice is shown in bright white, while average sea ice cover is shown in light blue to milky white. Adapted from WikiMedia. |

Ed Struzik: If they understood that there may be links between the weird weather we see down south and the rapid warming of the Arctic, they might care. Scientist Jennifer Francis recently did a very good job of describing how events unfolding in the Arctic may have been responsible for the frigid Arctic air and snow that hit some areas of Europe in 2012, including those that hadn’t seen those conditions in over half a century; how persistent weather patterns are responsible for droughts and heat, and how the record heat waves in Europe and Russia in the past several years have been linked to early snowmelt in Siberia.

Mongabay: What would a positive future for the Arctic mean?

Ed Struzik:

Food security for the people who live there, economic opportunities that benefit both northerners and southerners, an end to the geopolitical posturing that we see now, and guarantees that people down south will still be able to eat Alaska halibut and other Arctic fish. It may not end the weird weather we’re experiencing down here, but it may temper it or prevent it form getting even weirder.

A positive future would also include polar bears, narwhal, beluga, bowheads, barren-ground caribou, and other Arctic animals.

Why should we care about polar bears? Here’s what Robert Bartlett, one of the architects of Alaska statehood said in 1965 when polar bears were in danger of disappearing for other reasons than climate change.

“If, as some people fear, the polar bear is in danger of becoming extinct, the world will be less for the loss. If man can still take the time to see and understand the dignity and magnificence and uniqueness of polar bears, there is a good chance that man will meet and pass the necessary moral test.”

Related articles

|

Greenpeace sinks Lego’s $116 million deal with Shell Oil over Arctic drilling (10/09/2014) Lego has announced it will be severing its partnership with the oil giant, Shell, when the current contract expires after a clever campaign by environmental activist group, Greenpeace. Since 2011, Lego has been selling exclusive sets at Shell stations, but the companies’ relationship actually goes back decades. In 1966, the Danish toy company first began selling Lego sets with Shell’s brand stamped on them. |

|

The only solution for polar bears: ‘stop the rise in CO2 and other greenhouse gases’ (10/08/2014) Steven Amstrup, Chief Scientist for Polar Bears International, has worked diligently on polar bears for over 30 years. He radio-collared some of the first bears and discovered that annual activity areas for 75 tracked females averaged at a stunning 149,000 square kilometers. His recent work highlighted the cost of global warming to these incredible animals and the sea ice they so closely depend on. |

|

Throng of 35,000 walruses is largest ever recorded on land, sign of warming arctic (10/01/2014) A mass of thousands of walruses were spotted hauled up on land in northwest Alaska during NOAA aerial surveys earlier this week. An estimated 35,000 occupied a single beach – a record number illustrating a trend in an unnatural behavior scientists say is due to global warming. |

|

Scientists can now accurately count polar bears…from space (07/17/2014) Polar bears are big animals. As the world’s largest land predators, a single male can weigh over a staggering 700 kilograms (about 1,500 pounds). But as impressive as they are, it’s difficult to imagine counting polar bears from space. Still, this is exactly what scientists have done according to a new paper in the open-access journal PLOS ONE. |

|

31 activists arrested attempting to stop Arctic oil from docking in Europe (05/01/2014) Dutch police arrested 31 Greenpeace activists today, who were attempting to block the Russian oil tanker, Mikhail Ulyanov, from delivering the first shipment of offshore Arctic oil to the European market. |

|

From seals to starfish: polar bears radically shift diet as habitat melts (04/07/2014) One of the most iconic species of the ongoing climate change drama, polar bears have dropped in numbers as their habitat melts, with previous estimates forecasting a further 30 percent reduction within three generations. However, their situation may not be as dire as it seems. |

|

Apocalypse now? Climate change already damaging agriculture, acidifying seas, and worsening extreme weather (03/31/2014) It’s not just melting glaciers and bizarrely-early Springs anymore; climate change is impacting every facet of human civilization from our ability to grow enough crops to our ability to get along with each other, according to a new 2,300-page report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The massive report states definitively that climate change is already affecting human societies on every continent. |

|

Europe votes for an Arctic Sanctuary (03/13/2014) Yesterday, the European Parliament passed a resolution supporting the creation of an Arctic Sanctuary covering the vast high Arctic around the North Pole, giving official status to an idea that has been pushed by activists for years. Still, the sanctuary has a long road to go before becoming a reality: as Arctic sea ice rapidly declines due to climate change, there has been rising interest from governments and industries to exploit the once inaccessible wilderness for fish and fossil fuels. |