Little chance of reaching ‘sustainable population’ in next century

According to recent projections, the number of people living on Earth could exceed ten billion by the end of this century. Now, a new study has examined what it would take to reverse that unrelenting growth and achieve a sustainable population that is less threatening to biodiversity and ecosystems around the world. Short of a global catastrophe, scientists say, the only way to halt this population momentum is to institute a planet-wide one-child policy within a few decades.

The new study comes on the heels of a statistical projection released in September. It analyzed U.N. data from July and calculated how likely population is to end up in different ranges. In particular, it found an 80 percent chance for a population between 9.6 billion and 12.3 billion by century’s end, with the most likely figure at around 10.9 billion.

That number is not sustainable, according to Corey Bradshaw, a biologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia.

“Things like forest elephants? Kiss ’em goodbye. Tigers in India? They’re gone,” Bradshaw told mongabay.com.

Bradshaw and his Adelaide colleague, Barry Brook, examined whether it’s possible to rein in population growth in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They found that without draconian limits on the number of children per family, population growth is “virtually locked in.”

The researchers studied computer models of population over the next century, focusing particularly on how different parameters—or levers—affected their models.

“We’re not out there trying to predict there will be X number of people on the planet as of 2100,” Bradshaw said. “What we didn’t really know is the strength of the different levers one can pull.”

Bradshaw and Brook pulled on three levers. First was fertility: the average number of children women have. Next was mortality: the likelihood that people die by a certain age. And the last was primiparity: the average age at which women have their first child. They modeled “what if?” scenarios that adjusted these levers.

When researchers studied the ‘virtually locked-in’ population growth of the coming century, they found that population momentum could be too much to overcome. Photo by: Photograph by Muntasirmamunimran, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license. |

For instance, in a scenario that kept levers at 2013 levels, they found that population reached 10.42 billion by 2100, right in the middle of the statistical projections released in September. In a scenario the authors dubbed “realistic,” they cut mortality in half by 2100 to model improving diets and the availability of medicine. Additionally, they shifted primiparity to older ages and lowered fertility from its 2013 value of 2.37 children per woman to 2. Their model still predicted 10.35 billion people by 2100, a negligible difference in terms of sustainability.

To model what would happen if all governments globally restricted families to just one child, they examined two scenarios: smoothly reducing global fertility to 1 child by 2100, or more aggressively by 2045. In the former case, the population peaked in the middle of the century and then declined to around seven billion by 2100. In the more draconian case, population by 2100 shrank more quickly, ending at 3.45 billion.

Even this last figure is still bigger than some estimates of a sustainable human population, which fall between one and two billion. Those numbers are difficult to estimate because they depend heavily on social and technological developments, as well as how much people consume. But what’s clear is that population won’t even begin to approach these numbers in the coming decades, short of utter catastrophe.

“Our point was merely that in the short term our biggest gains in sustainability will be held by reducing per capita consumption, although underneath all that we must also reduce population,” Bradshaw said. “It will just take a lot longer to achieve.”

The point was well made, said biologist Thomas Lovejoy of George Mason University in Virginia, who coined the term “biological diversity” in the 1980s.

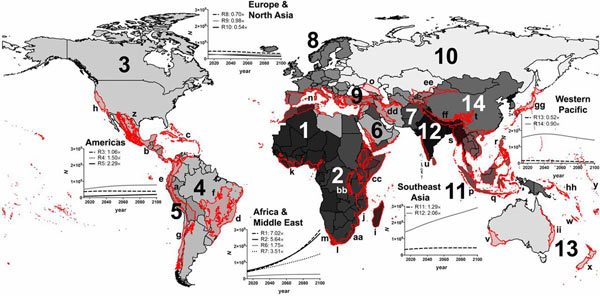

A figure from the paper showing regional breakdowns of population density in 2100. Numbers represent regions, letters and red borders represent areas with high biodiversity. Population density is represented by the shading, with darker areas indicating higher density. Insets show population plots for each region through 2100. Reproduced with permission from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Click to enlarge.

“The real value of this paper is bringing a sense of the magnitude, rate and complexity of the population problem home to those who worry about the supply side,” Lovejoy told mongabay.com.

Reducing consumption might ease another troubling trend, Bradshaw and Brook noted. Their models predicted that the regions with the planet’s highest biodiversity could also have the biggest population booms this century, increasing the stress on these ecological treasures.

“It really shows you where the most damage is likely if things continue as they are now,” Bradshaw said.

Population Scenarios |Create infographics

Citations:

- Bradshaw, C.J.A. and Brook, B.W. (2014). Human population reduction is not a quick fix for environmental problems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (46) 16610-16615.

Chris Cesare is a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Related articles

World population could surpass 13 BILLION by the end of the century

(09/18/2014) By 2100, over 13 billion people could be walking the planet. That’s the conclusion of a new study published today in Science, which employed UN data to explore the probability of various population scenarios. The new study further demolishes the long-held theory that human population growth will quit growing by mid-century and then fall.

Booming populations, rising economies, threatened biodiversity: the tropics will never be the same

(07/07/2014) For those living either north or south of the tropics, images of this green ring around the Earth’s equator often include verdant rainforests, exotic animals, and unchanging weather; but they may also be of entrenched poverty, unstable governments, and appalling environmental destruction. A massive new report, The State of the Tropics, however, finds that the truth is far more complicated.

Unrelenting population growth driving global warming, mass extinction

(06/26/2014) It took humans around 200,000 years to reach a global population of one billion. But, in two hundred years we’ve septupled that. In fact, over the last 40 years we’ve added an extra billion approximately every dozen years. And the United Nations predicts we’ll add another four billion—for a total of 11 billion—by century’s end.

David Attenborough: someone who believes in infinite growth is ‘either a madman or an economist’

(10/16/2013) Sir David Attenborough has said that people living in poorer countries are just as concerned about the environment as those in the developed world, and “exporting environmentalism” isn’t necessarily an “uphill struggle”. The veteran broadcaster said ideas about protecting the natural world were not unwelcome in less developed nations—but added that wealthier countries should work to improve women’s rights around the world to bring down birth rates and avoid overpopulation.

Humanity consumes this year’s resources 133 days too early

(08/20/2013) Today is Earth Overshoot Day, according to the Global Footprint Network and WWF’s Living Planet Report, which means the seven billion people on Earth have consumed the globe’s renewable resources for the year. In other words for the next 133 days humanity will be accumulating ecological debt by overdrawing on our collective resources.

Crop yields no longer keeping up with population growth

(06/26/2013) If the world is to grow enough food for the projected global population in 2050, agricultural productivity will have to rise by at least 60%, and may need to more than double, according to researchers who have studied global crop yields.