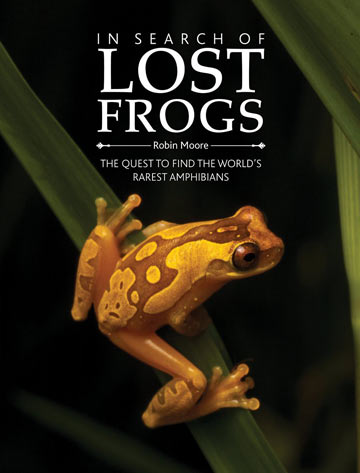

An interview with Robin Moore, author of the new book, In Search of Lost Frogs: The Quest to Find the World’s Rarest Amphibians

The Cuchumatan golden toad (Incilius aurarius) from the Cuchumatanes mountains of Guatemala, found during a search for lost salamanders. This species was only discovered as recently as 2012. It is so new to science that it has yet to be evaluated by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Robin Moore.

One of the most exciting conservation initiatives in recent years was the Search for Lost Frogs in 2010. The brainchild of scientist, photographer, and frog-lover, Robin Moore, the initiative saw intrepid conservationists scouring through leaf-litters, under rocks, and in streams for “lost” amphibians across 21 countries. While the campaign was rooted in the tragic loss of amphibian species around the world, it also brought a sense of hope—and excitement—to a whole group of animals often ignored by the global public—and media outlets. Now, Moore has written a fascinating account of the search from both behind the scenes and in the field. Entitled In Search of Lost Frogs, the new book includes a large selection of Moore’s incredible photos.

While the global campaign did not re-discover most of the 100 amphibians it targeted, it did indeed find frogs that had been lost for decades—and some even over a century. Moreover, the search uncovered several new species of amphibians and resulted in greater knowledge for many threatened amphibians. The search also inspired similar endeavors around the world, including one in India where an astounding 36 species were re-discovered.

|

But, perhaps most importantly, the campaign brought the message of the global amphibian crisis into the living rooms and offices of millions of people around the world. Unlike many conservation campaigns, the Search for Lost Frogs was widely covered by the mainstream media. And instead of just delivering a message of despair, it also built on the excitement of exploration and the great beauty of these often-overlooked creatures.

Formally with Conservation International, Moore is now a co-founder and conservation officer with the Amphibian Survival Alliance as well as the Creative Director of Frame of Mind, a group that connects kids with nature through photography.

In a 2014 interview with mongabay.com, Robin Moore talks about how we can help frogs, what conservationists can learn from the success of the campaign, and whether or not a Search for Lost Frogs 2 is in the making!

INTERVIEW WITH ROBIN MOORE

An Andes poison dart frog (Ranitomeya opisthomelas) in the Chocó rainforest. This species is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Mongabay: What’s you background and what drew you to amphibians?

Robin Moore: Some of my earliest memories are of wading through peat bogs in the Scottish highlands in search of newts and frogs. It felt intoxicating to be searching for creatures that had rubbed ankles with the dinosaurs in such a wild and majestic setting. I felt like an intrepid explorer. What really set me apart from most kids, however, was that I never outgrew my fascination. I pursued a PhD in Biodiversity Conservation, with a focus on frogs, and embarked on a career in research. But the realization that frogs were in trouble drew me towards being more actively involved in their conservation. I joined Conservation International, where I spent close to eight years supporting amphibian conservation programs around the world and trying to rally support for their protection. It was during this time that I spearheaded the Search for Lost Frogs and helped to form and build the Amphibian Survival Alliance, now the world’s largest partnership for amphibian conservation.

AMPHIBIAN MASS EXTINCTION

Mongabay: There’s lots of numbers and statistics regarding the current extinction crisis hitting amphibians, but what are we really witnessing? How bad is it?

Robin Moore. Photo by: Robin Moore. |

Robin Moore: It is bad. Amphibians are survivors—they have been around for more than 300 million years and have made it through five mass extinctions. Since the dinosaurs disappeared, the Earth has been losing species at a rate of about one species in a million every year—to put that into context for amphibians, that equates to one amphibian species every 143 years. In the past few decades the rate of extinction has sped up to around 1,000 times that. Over 3,000 species of amphibians are currently threatened with extinction according to the IUCN, and according to a recent report by WWF, more than three quarters of populations of freshwater species have declined over the past 40 years. No matter how you spin this, it is not good.

Mongabay: Will you tell us about chytrid fungus. Why has this proven so devastating to amphibians?

Robin Moore: The amphibian chytrid fungus may be responsible for the greatest disease-caused loss of biodiversity in recorded history. The fungus causes a disease in amphibians called chytridiomycosis that leads to death by cardiac arrest. It has been devastating to hundreds of amphibian species worldwide for a number of reasons. Firstly, fungi are neither plants nor animals—they belong to a separate Kingdom and they follow different rules. Like animals they need to eat to survive, but they can retreat into spores and survive long periods without feeding. They can also live outside of their host, and they can switch hosts relatively easily. These traits have helped the chytrid fungus spread into all continents on which amphibians are found. They can also reproduce sexually, meaning that when they encounter another fungus of the same species in a new environment, they are able to recombine into a potentially more virulent strain. There is evidence that, as the fungus spread through North, Central and South America, it evolved into a deadly superbug capable of wiping out populations and species. Because the fungus can switch hosts it is able to wipe out entire species without exterminating itself.

Mongabay: How has global warming perhaps exacerbated the impacts of the chytrid fungus?

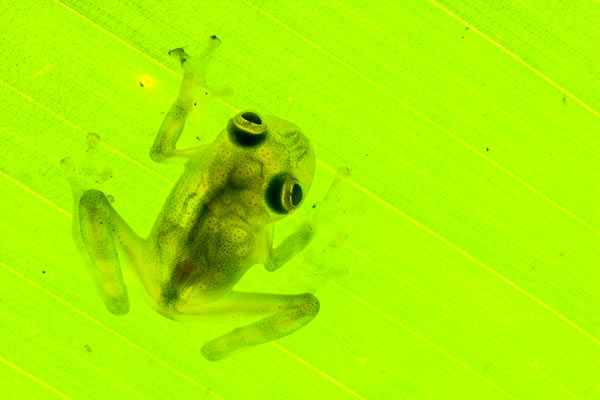

Reticulated glass frog (Hyalinobatrachium valerioi) on a leaf in the Osa Peninsula. Glass frogs are so-named because of their virtually transparent skin. This species is considered Least Concern. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Robin Moore: Amphibians are succumbing to a lethal cocktail of threats that act synergistically. Because many species have vanished almost overnight without leaving much in the way of evidence, it is often difficult to pinpoint exactly what drove the species to extinction, and opinions often vary widely on the respective roles of climate change and disease. Regardless of what is pulling the trigger on a species, the gun is being loaded by habitat loss, disease, climate change and pollution, all of which are likely to be stressing animals and weakening immune systems. Climate change is undoubtedly influencing the dynamics of the disease and adding yet another stressor for amphibians to contend with.

THE SEARCH

Mongabay: Will you tell us how you got the idea for a Search for Lost Frogs? And what’s the definition of a lost species?

Robin Moore: I had been at Conservation International (CI) for close to five years trying to communicate the plight of amphibians to the general public. People generally weren’t that interested, and I quickly realized that amphibians had an image problem. Rather than continue to hit people over the head with alarming statistics I decided to try a different approach to engage people. I brainstormed with colleagues and we came up with the idea of putting out a call for “lost” amphibians. I ran with the idea. I started to compile a list of lost species, tapping into our network 700 amphibian experts around the world for input. There was no strict definition of what constituted a lost species so we had to come up with one. We decided that the species could not have been seen within the last 10 years (at least two generations for most amphibians), and it had to be nominated by an expert. The list quickly grew to 100 species, at which point I ran the idea past the communications team at CI, and they loved it. We produced a poster of the Top Ten Most Wanted, and that really seemed to excite people. To make things more interesting, we raised support for 126 researchers to search for lost species in 21 countries. We launched the campaign on August 9, 2010, and the media immediately picked it up. It just seemed to resonate.

Mongabay: What do you see as the biggest success and failures of the global search?

A male hourglass frog (Dendropsophus ebraccatus) calls to a female on a blade of grass below in the Osa Peninsula, one of the biologically richest places on earth. This species is considered Least Concern. Photo by: Robin Moore. |

Robin Moore: Most research teams failed to find their lost species—but this is what we expected. These animals are lost for a reason—so it was something of a somber reminder of the plight of amphibians worldwide. A few rediscoveries stood out as being particularly remarkable. The Hula painted frog in Israel, for example. This frog vanished in the 1950s after its wetland home was drained like a giant bathtub. After forty years without trace, the frog was the first amphibian to be listed as Extinct by the IUCN, and it became a symbol of extinction in Israel. In response to public pressure, the wetland was partially re-flooded in the 1990s, and while some of the wildlife came back the Hula painted frog remained a poignant reminder of what had been lost. The frog was one of our Top Ten Most Wanted species globally. And remarkably, a year after the Search for Lost Frogs launched, a reserve warden stumbled upon a live Hula painted frog – 55 years after it was last seen. It was a reminder that nature can surprise given a chance.

I think the biggest success of the campaign was that it succeeded in grabbing the attention of a global media, and in doing so it gave us a platform to deliver more nuanced messages about the plight of amphibians.

Mongabay: Why do you think India’s search was so successful? What can other frog conservationists take away from India’s 36 rediscovered frogs?

Robin Moore: The Lost! Amphibians of India campaign was spearheaded by the brilliant Dr. Biju, who doesn’t do things by halves. The search was brilliantly masterminded and executed, engaging both scientists and citizen scientists in the hunt, and Biju and colleagues knew exactly where and when to target their searches for these lost species. I think it highlights just how little studied some of these forests were that the frogs—some of them brilliant greens and yellows—had gone for decades without being recorded.

Mongabay: People usually don’t think of Haiti as a wildlife hotspot, but the country has lots of frogs found no-where else. How are these species doing in light of the country’s challenges?

The Finca Chiblac salamander (Bradytriton silus) from the Cuchumatanes mountains of Guatemala. This species is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Robin Moore: They are clinging on—almost all of Haiti’s frog species are threatened with extinction. But there are fragments of cloud forests remaining, and we are currently working with local and international partners to raise support to establish the first ever network of private protected areas in the country. If we can protect the last fragments then we have something to build on.

Mongabay: Madagascar has nearly 300 amphibians, almost all of which are found no-where else. Why was the country not included in the search? What are is the current state of amphibians there?

Robin Moore: Until earlier this year Madagascar was, curiously, free from any signs of the chytrid fungus that has wreaked havoc elsewhere, so enigmatic and rapid declines were not witnessed in Madagascar. Madagascar also has a relatively active and engaged research community, so its unique species are relatively well monitored, hence no Malagasy species were nominated for the list of lost species. Madagascar has become something of a model for how an active and engaged community can develop and implement a conservation strategy for amphibians. I attended a workshop in Antananarivo, the capital, in 2007 to help develop this strategy—I was blown away by the fact that there were around 80 engaged participants, including government officials. But we are actually at a critical juncture in the conservation of amphibians in Madagascar. Following the first sign that the chytrid fungus has made its way to the island, trials started to test the effectiveness of some novel approaches to combating infection through probiotic therapy. This involves augmenting the skin of the frogs with beneficial bacteria (much in the same way we augment our stomach fauna by eating probiotic yogurt) that have been found to give frogs a fighting chance at surviving infection. No mass mortalities have been detected yet, but we want to be prepared with our best weapons if they are. So, Madagascar could be poised to become a living laboratory for testing novel approaches to treating the fungus in the wild.

Mongabay: While the rediscovery of lost species seems to capture the most attention, it seems to me that what happens next is most important. What do we need to do to make sure these species don’t vanish again—and this time for good?

The variable harlequin frog (Atelopus varius) a Critically Endangered species that was feared extinct before being rediscovered in 2003. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Robin Moore: Firstly, we need to understand why some individuals and species survived while others around them disappeared—this could help us prevent them from disappearing again. Most rediscovered species are subject to active research and monitoring programs by local universities. Secondly, we need to assess the most pressing threats to the survival and recovery of these species. This is often habitat loss—which remains the primary threat to the long-term survival of most species worldwide. In order to address this threat the Amphibian Survival Alliance is working with partners around the world to identify and protect the most critical habitats. So, we do have a global funding mechanism for supporting the protection of amphibians, but we need to scale this up to really meet the challenge.

FROG PUBLICITY

Mongabay: Your global Search for Lost Frogs garnered tons of media. Do you think other conservation and research efforts should consider a similar tact? Such as a search for lost mammals or lost reptiles?

Robin Moore: I think it does have value in engaging people in the conservation of some of the more maligned or forgotten creatures. It’s hard to get much love for reptiles, and so more creative approaches are often needed to get the conservation message in front of people. This approach proved to be effective for getting media attention for frogs, and I believe it could be effectively expanded to other taxonomic groups.

Mongabay: One of conservation’s biggest hurdles is funding. How was the Search for Lost Frogs funded? Are there some creative ways such initiatives could be funded, i.e. as a part of a documentary or through crowd-sourced funding?

A juvenile macaya breast-spot frog (Eleutherodactylus thorectes) a Critically Endangered species in the Massif de la Hotte. One of the smallest frogs in the world, it was rediscovered in 2010 after close to two decades. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Robin Moore: We have been lucky enough to receive support over the years from a couple of loyal individuals who are passionate about amphibian conservation, and this enabled us to rally support for this campaign—it also helped to have the backing of the communications team at Conservation International. Because it really captured people’s imaginations, we also got some donations online on a site dedicated to the campaign. Crowd-funding is something I dabbled in to support another project aimed at elevating the profile of amphibians called Metamorphosis—we successfully raised a few thousand dollars. The Amphibian Survival Alliance is also working to leverage existing support by partnering with groups that have a broader focus than just amphibians, in addition to companies who are interested in supporting conservation.

Mongabay: Conservation groups, who spend the bulk of their funds on big mammals, often argue that protecting these animals protects all biodiversity in the area. Does the amphibian crisis negate that logic? Should conservation groups start widening the pool?

Robin Moore: This logic does sometimes apply—by protecting the home of a large wide-ranging predator you may indeed be protecting myriad other species. Flagship species are important for generating support for conservation—no species lives in isolation so it is ultimately about protecting the ecosystem that they call home. But not every flagship species is also an umbrella species, and this is when this logic can get a bit dicey, and this is where we really need to question the return on investment. Lu Zhi, a panda expert from Beijing University, has called efforts to reintroduce pandas to the wild as their habitat is being swallowed up as “pointless as taking off the pants in order to fart.” And yet we continue to reintroduce pandas into dwindling habitat even though the amount this costs could save hundreds of amphibian species from extinction. Now, of course, it is not a zero sum game—those amphibians are not nearly as effective at pulling at the heartstrings as the panda. It is human nature to try to save the species we like the most. But, with the rampant hemorrhaging of life from our planet, I do think we need to take a long hard look at what it is we are trying to save and why. I think we do need to widen the pool and I admire those groups that are thinking outside the panda to raise the profile of some of the more maligned and forgotten animals. The EDGE of Existence program of the Zoological Society of London has scored animals on how Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered they are, and used this as a basis for prioritizing their importance for conservation. I am all for such bold and creative approaches to marketing the conservation of species that are typically left out in the cold.

Mongabay: You mention the importance of photography for amphibians. What do photos reveal that our eyes often miss?

A glass frog, Hyalinobatrachium ruedai, peers through a leaf in the Choco of Colombia as we search for lost frogs. This species is considered Least Concern. Photo by: Robin Moore. |

Robin Moore: Photographs can reveal a world of colors and textures that our naked eye does not depict. Photographs also allow us to share and celebrate these beautiful and cryptic creatures with those who may never be lucky enough to see one in the wild. Just as a sunset is better shared, so is the sight of a remarkable frog.

Mongabay: How can we get people to really care about frogs?

Robin Moore: I think our best bet, with most people, is to appeal to that childlike curiosity with the world that is deep within every one of us. Many of us spent our childhoods fishing for frogs and raising tadpoles, and the realization that our children and our children’s children may not have that same opportunity is deeply saddening. The thought of my son one day asking what we were doing while the frogs were vanishing around us sends a chill up my spine. When we talk of the value of species we tend to talk in terms of their economic or ecological value—to appeal to the mind and not the heart. But it is the emotional and intellectual value of frogs and salamanders that I think is more important on a personal level to most people. We need to be telling more stories that remind people how much amphibians enrich our shared world, and we need to try to put the disappearance of frogs and salamanders into the context of people’s every day lives.

One of the biggest threats to frogs is the widely held misconception that we are somehow above, or superior to nature, rather than a part of it. The only way to really change this mindset is through personal experience. It is with this in mind that I co-founded a program in Haiti called Frame of Mind that empowers youth to connect with their natural and cultural worlds through photography and visual storytelling. The camera gives the young Haitians a means of capturing and sharing the beauty around them, and of telling visual stories that help them to redefine their relationship with nature. It has been a transformative experience for both the youth and for me. I think that every child should be given the opportunity to have their eyes opened by the wonder of nature.

GOING FORWARD

Mongabay: Given how many species have very likely been lost, what gives you hope when looking at the state of amphibians today?

A new species of beaked toad—later dubbed the ‘Monty Burns Toad’ on account of its similarity to the nefarious villain in the Simpsons—found in the Choco of Colombia whilst searching for a lost species. This species has yet to be formally described. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Robin Moore: We have identified 250 amphibian species that have not been seen in decades, and the IUCN estimates that more than half of these are likely to be Extinct. And this does not include ghost species—those that have gone extinct before they have even been named. Overall, it is quite a bleak landscape. What gives me hope are those frogs that have made an incredible reappearance years or decades after they vanished. These are a reminder that nature can continue to surprise us. As long as there are still frogs, there is hope. George Monbiot wrote that an ounce of hope is worth a ton of despair—and I think this is an important reminder as we try to engage people in conservation. We need grounded hope to remind us what we are fighting for.

Mongabay: What can people do to help the world’s amphibians?

Robin Moore: The Amphibian Survival Alliance has recently formed as a platform to engage people and organizations in addressing the most pressing threats to amphibians around the world. I would strongly advise hopping onto amphibians.org to see what people are doing around the world, and to find out how you can become involved. People can support the work of groups around the world, organize fundraisers, volunteer for a local group monitoring amphibians, or give a talk at a local school. There are many creative ways to join the conversation and make a difference.

Mongabay: Any plans for a sequel to the Search for Lost Frogs?

Robin Moore: Having seen the incredible response to the Search for Lost Frogs, I am definitely inspired to build on this. What that sequel will look like, I can’t really say just yet!

Gliding treefrog (Agalychnis spurrelli) with mushrooms, found on the last night in the Osa Peninsula. This species is Least Concern. Photo by: Robin Moore.

The nimble long-limbed salamander (Nyctanolis pernix) in the Cuchumatanes of Guatemala. This species is considered Endangered. Photo by: Robin Moore.

La Hotte glanded frog (Eleutherodactylus glandulifer) a Critically Endangered species on the Massif de la Hotte, Haiti. Last seen 1991 until it was rediscovered in 2010. Photo by: Robin Moore.

A canal zone treefrog (Hypsiboas rufitelus) in the Chocó of Colombia with a shock of red webbing between the toes. This species is listed as Least Concern. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Researcher Vance Vredenburg swabs a mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa) to test for the presence of the amphibian chytrid fungus, responsible for wiping out frogs from pristine lakes in the high Sierra Nevadas of California. This species is listed as Endangered. Photo by: Robin Moore.

Related articles

Selective logging hurts rainforest frogs

(08/21/2014) Selective logging in India’s Western Ghats forests continues to affect frogs decades after harvesting ended, finds a new study published in Biotropica. The research assessed frog communities in logged and unlogged forests in Kalakad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve and found that unlogged forests had twice the density of frogs as areas logged in the 1970s.

New skeleton frog from Madagascar is already Critically Endangered

(08/20/2014) Sometimes all it takes is fewer clicks. Scientists have discovered a new species of frog from Madagascar that stuck out because it “clicked” less during calls than similar species. Unfortunately the scientists believe the new species—dubbed the Ankarafa skeleton frog—is regulated to a single patch of forest, which, despite protected status, remains hugely threatened.

Yellow spots, orange stripes: vivid new frog species discovered in Malaysia

(08/05/2014) Scientists have identified a new species of frog on the Malay Peninsula. The newly named Hylorana centropeninsularis was discovered in a peat swamp and genetic analyses revealed that it is evolutionarily distinct from its stream-dwelling cousins.

Ecologists are underestimating the impacts of rainforest logging

(07/31/2014) Ecologists may be underestimating the impact of logging in old-growth tropical forests by failing to account for subtleties in how different animal groups respond to the intensity of timber extraction, argues a paper published today in the journal Current Biology. The study, led by Zuzana Burivalova of ETH Zurich, is based on a meta-analysis of 48 studies that evaluated the impact of selective logging on mammals, birds, amphibians, and invertebrates in tropical forests.

Desperate measures: researchers say radical approaches needed to beat extinctions

(07/24/2014) Today, in the midst of what has been termed the “Sixth Great Extinction” by many in the scientific community, humans are contributing to dizzying rates of species loss and ecosystem changes. A new analysis suggests the time may have come to start widely applying intensive, controversial methods currently used only as “last resort” strategies to save the word’s most imperiled species.

‘Exciting implications’ for conservation: new technology brings the lab to the field

(06/26/2014) Times have changed, and technological advancements have scaled down scientific equipment in terms of both size and cost. Among them are the tools and procedures needed to conduct molecular genetic analysis. A study published this week explored the potential applications of this new technology, and found that it allows both researchers and novices alike to analyze DNA in the field easily, cheaply, and effectively.

Dancing frogs: scientists discover 14 new species in India (PHOTOS, VIDEO)

(05/16/2014) Scientists have discovered 14 new species of frogs in the mountainous tropical forests of India’s Western Ghats, all of which are described in a recent study published in the Ceylon Journal of Science. The new species are all from a single genus, and are collectively referred to as “dancing frogs” due to the unusual courtship behavior of the males.

New relative of the ‘penis snake’ discovered in Myanmar

(04/17/2014) Scientists have discovered a new species of limbless amphibians, known as caecilians, in Myanmar. Dubbing the species, the colorful ichthyophis (Ichthyophis multicolor), the researchers describe the new amphibian in a recent paper published in Zootaxa. The world’s most famous caecilian is the so-called penis snake (Atretochoana eiselti) which was rediscovered in Brazil in 2011.

Amphibian pandemic may have hit Madagascar, hundreds of species at risk of infection

(04/11/2014) Madagascar is one of the world’s hotspots for amphibian diversity, home to so many frog species that many of them don’t even have names. But soon the island may also harbor a fungus causing drastic declines – even extinctions – of frogs around the world. Ironically, the wildlife trade that’s often blamed for helping spread the disease may also give scientists a chance to prevent it.

The incredible shrinking salamander: researchers find another casualty of climate change

(04/04/2014) Climate change is contributing to a slew of global problems, from rising seas to desertification. Now, researchers have added another repercussion: shrinking salamanders. Many amphibian populations around the world are currently experiencing precipitous declines, estimated to be at least 211 times normal extinction rates. Scientists believe these declines are due to a multitude of factors such as habitat loss, agricultural contamination, and the accidental introduction of a killer fungus, among others.

Several Amazonian tree frog species discovered, where only two existed before

(03/18/2014) We have always been intrigued by the Amazon rainforest with its abundant species richness and untraversed expanses. Despite our extended study of its wildlife, new species such as the olinguito (Bassaricyon neblina), a bear-like carnivore hiding out in the Ecuadorian rainforest, are being identified as recently as last year. In fact, the advent of efficient DNA sequencing and genomic analysis has revolutionized how we think about species diversity. Today, scientists can examine known diversity in a different way, revealing multiple ‘cryptic’ species that have evaded discovery by being mistakenly classified as a single species based on external appearance alone.

Frog creates chemical invisibility cloak to confuse aggressive ants

(03/14/2014) The African stink ant creates large underground colonies that are home to anywhere from hundreds to thousands of ants, and occasionally a frog or two. The West African rubber frog hides in the humid nests to survive the long dry season of southern and central Africa. However, the ant colonies are armed with highly aggressive ant militias that fight off intruders with powerful, venomous jaws. So how do these frogs escape attack?