Road development in Brazilian Amazon states surges, 95 percent of deforestation occurs within 50km of roads

When a new road centipedes its way across a landscape, the best of intentions may be laid with the pavement. But roads, by their very nature, are indiscriminate pathways, granting access for travel and trade along with deforestation and other forms of environmental degradation. And as the impacts of roads on forest ecosystems become clear, governments and planning agencies reach a moral crossroads.

Roads have the potential to greatly cut costs for businesses and farms, grant rural communities access to healthcare facilities and bolster economic growth. But the trouble with roads is that they can easily pave the way for more destructive activities. As they are built, loggers, miners, land speculators, ranchers and other potentially eroding forces follow swiftly behind roads crews, turning the relatively small line of deforestation caused by a road into a an amoeboid-like growth of deforestation. Poorly planned road development can begin a cascade of changes in the environment. As forests dry out along roadways, issues like wildfires and forest degradation along edges can weaken ecosystems.

The beginning of the trans-Amazonian highway at Cabedelo, Paraíba, Brazil.

“The incredible expansion of roads into the last remaining tropical wildernesses—this is a true environmental crisis, because such roads open up a Pandora’s box of problems, often leading to large-scale forest destruction and degradation,” said Dr. William Laurance of the Centre for Tropical Environmental & Sustainability Science at James Cook University in Australia.

In fact, 95 percent of forest loss occurs within 50 kilometers (31 miles) of a road. This number, from the Alliance of Leading Environmental Researchers and Thinkers (ALERT), is especially troubling when one considers that the vast majority (around 90 percent) of projected road development in the coming decades will occur in countries with the highest levels of biodiversity.

A 2013 study published in the journal Regional Environmental Change found that road networks in the Brazilian Amazon grew by almost 17,000 kilometers (10,000 miles) per year between 2004 and 2007.

“Even though roads often occupy less than two percent of a country’s land surface, they may have an ecological impact on an area up to ten times as large,” the researchers said in a statement. “These indirect effects can include changes in air and soil temperature and moisture, as well as restrictions on the movement of animals.”

Since 2005, government measures have slowed forest loss in Brazil, and the nation is now a global leader in decreasing deforestation but the fact remains that the Brazilian Amazon has lost nearly 20 percent of its forest cover since the 1970s and deforestation is still a major issue throughout the Amazon Basin.

Brazil’s first paved roads and “the arc of deforestation”

In the Brazilian states containing the Amazon rainforest, only two federal highways were paved and drivable year-round before the late 1990s: the Belém-Brasília Highway (built in 1958) and the Cuiaba-Porto Velho Highway (1968). In the twenty years after it was paved, an estimated two million settlers entered the Amazon Basin via the Belém-Brasília Highway and subsequent smaller roads were built stemming from the highway.

The completion of more and more paved roads (BR-316,BR-308, BR-010, BR-226, BR-153, and BR-060, in particular) allowed further waves of settlers to make their way north and west into the forest. These highways built the foundation for Brazil’s infamous “arc of deforestation” – the advancing agricultural frontier across Para, Mato Grosso, and Rondonia in Brazil.

Pasture and legal forest reserve near the arc of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

The Trans-Amazonian Highway: East to West across Brazil

The 4,000-kilometer (2,500-mile) Trans-Amazonian Highway slices through South America from East to West and “has been leading to massive forest loss in Peru and Brazil” said Laurance.

Inaugurated in 1972, the route opened up a swath of upland forest in the heart of the Amazon to ranching, land prospectors, mining and settlers. In the 1990s and early 2000s deforestation rates rose as high as 25,000 square kilometers (9,700 square miles) per year — an area twice the size of Massachusetts.

The highway, most of which is the BR-320, starts in Recife and João Pessoa and crosses Brazil to Cruzerio do Sul, Acre, with the exception of a stretch that was never built between Lábrea and Boca do Acre. The BR-317 and BR-364 make up the stretches connecting Boca do Acre with Cruzeiro do Sul.

1999 planning map for the Trans-Amazonian Highway. Photo courtesy of Ministério dos Transportes in Brazil.Click to enlarge.

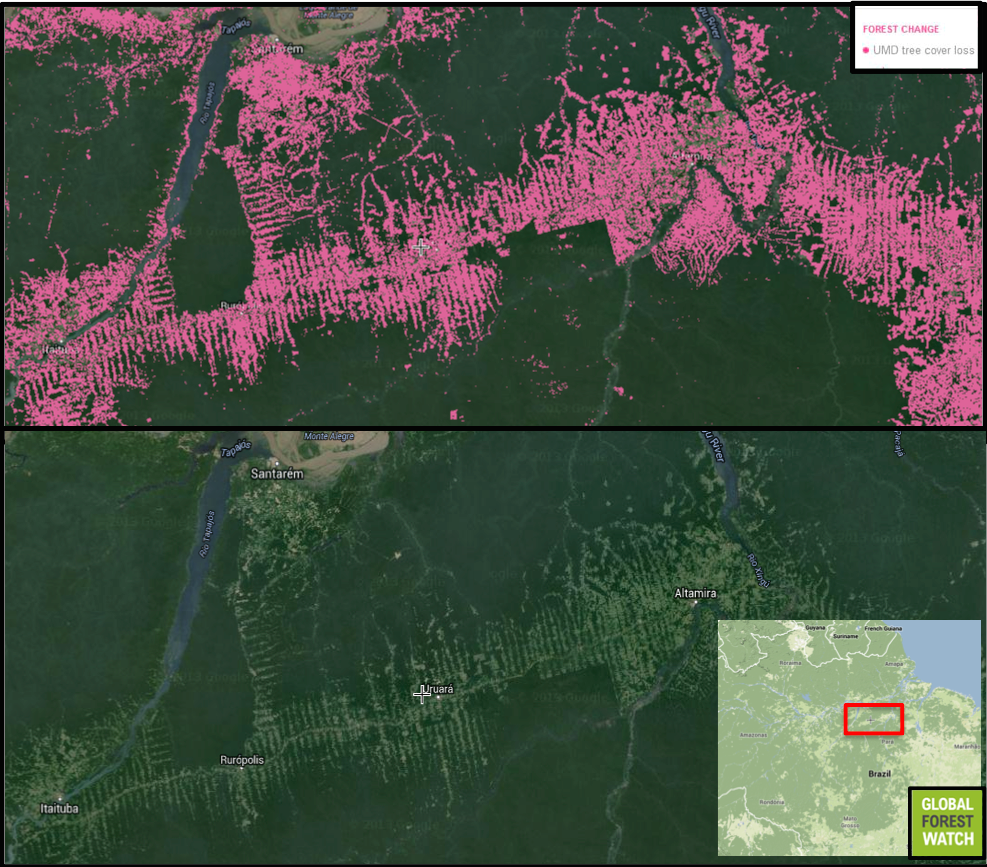

Road development has led to massive deforestation along with highway, here visible via satellite. According to data from Global Forest Watch, of the approximately 13 million hectares included in the rectangular section, more than 1.3 million hectares — or 10 percent — has been cleared during the past 14 years. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

The Interoceanic Highway: connecting Peru and Brazil

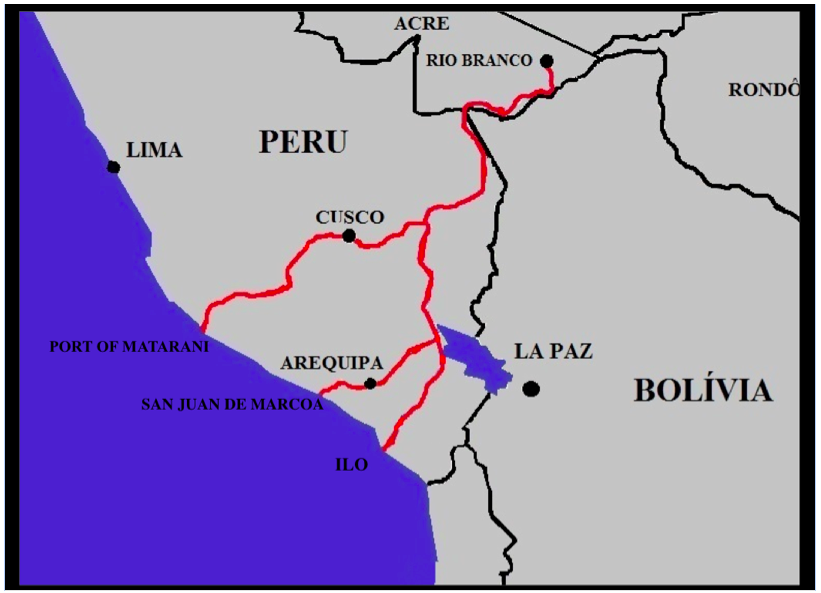

The Interoceanic Highway in Peru links the BR-317 in Assis, Brazil, to three of Peru’s southern ports. The most recent phase of the highway was completed in 2011 with the building of a bridge over the Madre de Dios River. This section of highway completes what is now the first paved roadway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in South America.

Peru is counting on the road as a means of opening up its long-neglected interior for development, but the road is controversial, as it cuts through the Peruvian Amazon and comes perilously close to some of the most pristine and biodiverse areas of the region: Tambapota National Reserve, the Madre de Dios Reserve, the Los Amigos Conservation concession, and Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

“The Interoceanic Highway and its growing network of secondary roads has resulted in a slowly expanding band of deforestation across the southern Peruvian Amazon, a pattern clearly visible in the Global Forest Watch data,” Matt Finer, a research specialist with Amazon Conservation Association (ACA) told mongabay.com. “The data also suggests that the highway is facilitating the explosion of illegal mining in southern Peru, which has also become a major driver of deforestation in recent years.”

The Inter-oceanic Highway in Peru. Photo by Hochgeladen von Gaban. Click to enlarge.

The Interoceanic Highway connects Brazil and Peru through the Amazon Basin, weaving its way in between the Tambapota National Reserve, the Madre de Dios Reserve, the Los Amigos Conservation concession, and Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Interactive view. Click to enlarge.

The BR-163: Cutting the Amazon from North to South

The BR-163 is another prominent highway that, according to Laurance is “cutting a slash up through the central Amazon.” The 1,7000-kilometer (1,150-mils) highway runs north to south from Cuiaba, the capital of Mato Grosso, to Santarem, linking agro-commodity production areas to the export ports in the Amazon River and connecting to the Transamazonica Highway (BR-230) and the “arc of deforestation.”

The highway was built in the 1970s and, until recently, has been primarily a potholed dirt road. In 2004, the Federal government made plans to pave the road, and in 2006 made promises to mitigate environmental and social impacts caused by road development.

In a 2012 statement, Greenpeace commented that, “nearly 80 percent of the highway has been paved at a cost of nearly one million Reais ($450,000) per kilometer. Yet many of the social and environmental initiatives planned have not been implemented. Of the 6.8 million hectares of protected areas created in 2006, many areas have now been reduced, boundaries redefined and only a few have management plans.”

The BR-163 begins in Guaira, and ends in Santarém Parque Nacional do Jamanxim and connects with BR-230. The BR 230 cuts through the Parque Nacional da Amazônia. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Interactive view. Click to enlarge.

Building better roads

The status of land ownership, and therefore accountability, surrounding highways is complicated. In Brazil, for example, the federal government controls unclaimed areas but there are also extensive private holdings, indigenous lands, state lands, and both state and federal protected areas.

According to Laurance, one way to curb deforestation along roadways is to create protected areas and parks .

“This is regarded as one of the best strategies for limiting deforestation when a new road cuts into a forest,” Laurance said. “It’s not entirely effective, but you generally get a lot less deforestation near roads if the land has legal protection.”

This all begs the question: where should we build roads, and where should we not? Laurance is currently working with a team on a “Global Road Map” that will identify where roads should and shouldn’t be located, across the entire world.

“One key place to improve or build roads is in areas that have large yield gaps (underperforming agriculture), where roads can have large benefits but relatively limited environmental costs,” Laurance said. “I’m excited about this because I think it’s something that’s really needed—a proactive approach to road planning.”

}}

Related articles

30% of Borneo’s rainforests destroyed since 1973

(07/16/2014) More than 30 percent of Borneo’s rainforests have been destroyed over the past forty years due to fires, industrial logging, and the spread of plantations, finds a new study that provides the most comprehensive analysis of the island’s forest cover to date. The research, published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, shows that just over a quarter of Borneo’s lowland forests remain intact.

Regional court kills controversial Serengeti Highway

(06/23/2014) The Serengeti ecosystem got a major reprieve last week when the East African Court of Justice (EACJ) ruled against a hugely-controversial plan to build a paved road through Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park. The court dubbed the proposed road ‘unlawful’ due to expected environmental impacts.

Feather forensics: scientist uses genes to track macaws, aid bird conservation

(06/17/2014) When a massive road project connected the ports of Brazil to the shipping docks of Peru in 2011, conservationists predicted widespread impacts on wildlife. Roads are a well-documented source of habitat fragmentation, interfering with access to available habitat for many terrestrial and tree-dwelling species. However, it wasn’t clear whether or not birds are able to fly over these barriers.

Oil company breaks agreement, builds big roads in Yasuni rainforest

(06/05/2014) When the Ecuadorian government approved permits for an oil company to drill deep in Yasuni National Park, it was on the condition that the company undertake a roadless design with helicopters doing most of the leg-work. However, a new report based on high-resolution satellite imagery has uncovered that the company, Petroamazonas, has flouted the agreement’s conditions, building a massive access road.

Scientists discover ‘shark’ in Sumatran forest

(05/28/2014) In early April, Indonesian scientists discovered an endangered freshwater fish in the Harapan rainforest of Jambi. The species had never before been observed in the region, and is declining elsewhere throughout its range.

Scientists urge ban on roads in intact wilderness areas

(03/21/2014) A group of prominent scientists chose to mark the second International Day of Forests by urging the world to support an initiative that aims keep wild areas free of roads. Roadfree, an initiative led by Member of the European Parliament Kriton Arsenis, has been growing in prominence over the past year, gaining supporters ranging from indigenous rights leaders to deep ecologists. Now the Alliance of Leading Environmental Researchers and Thinkers (ALERT) has thrown its weight behind the concept.

Proposed rail and road projects could devastate Nepal’s tigers and rhinos

(02/06/2014) Chitwan National Park is a conservation success story. Since its establishment in 1973 the park’s populations of both Bengal tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) and one-horned rhinos (Rhinoceros unicornis) have quintupled, a success achieved during a time when both species have been under siege globally by poachers. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the park is also a vital economic resource for locals: last year the park admitted over 150,000 tourists who brought in nearly $2 million in entry fees alone. But all this is imperiled by government plans for a new railway that would cut the park in half and a slew of new roads, according to a group of international conservationists known as the Alliance of Leading Environmental Researchers and Thinkers (ALERT).

Next big idea in forest conservation? Global road map to mitigate damage from roads

(01/17/2014) In the world of conservation, Dr. William Laurance is a household name. He has worked in tropical systems, worldwide, for over 25 years, publishing over 300 articles, five books and receiving numerous awards and honors for his work as a researcher, science communicator, and conservation practitioner, including one of Australia’s highest scientific honors, the Australian Laureate Award.

High-living frogs hurt by remote oil roads in the Amazon

(01/14/2014) Often touted as low-impact, remote oil roads in the Amazon are, in fact, having a large impact on frogs living in flowers in the upper canopy, according to a new paper published in PLOS ONE. In Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park, massive bromeliads grow on tall tropical trees high in the canopy and may contain up to four liters of standing water. Lounging inside this micro-pools, researchers find a wide diversity of life, including various species of frogs. However, despite these frogs living as high as 50 meters above the forest floor, a new study finds that proximity to oil roads actually decreases the populations of high-living frogs.