Green under siege: world’s biodiversity hotspots 85 percent impacted

With only 3.5 percent intact vegetation left in the Atlantic Forest, it is the world’s most imperiled biodiversity hotspot. This is an image of intact forest in Intervales State Park. Photo by: Bjørn Christian Tørrissen/Creative Commons 3.0.

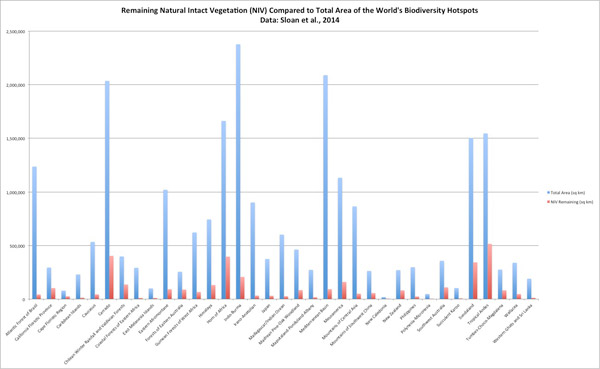

The world’s 35 biodiversity hotspots—which harbor 75 percent of the planet’s endangered land vertebrates—are in more trouble than expected, according to a sobering new analysis of remaining primary vegetation. In all less than 15 percent of natural intact vegetation is left in the these hotspots, which include well-known wildlife jewels such as Madagascar, the tropical Andes, and Sundaland (Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula). Worse yet, nearly half of the biodiversity hotspots have less than 10 percent primary vegetation left with five of these containing less than five percent.

“If we lose the hotspots we’ll say goodbye to over half of all species on Earth. It would be comparable to the mass-extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs,” said William Laurance, a co-author of the study in Biological Conservation with James Cook University.

The world’s biodiversity hotspots were first identified in a seminal paper in 2000. At the time, scientists listed ten hotspots; since then, the number has grown to 35. But biodiversity hotspots are more than just regions of high biodiversity, they must also have lost most of their vegetation, around 70 percent. Currently, the 35 hotspots house 77 percent of the known mammals, birds, and herps (amphibians and reptiles); about half of the world’s plant species; and over 40 percent of the world’s endemic terrestrial vertebrates. These hotspots include well-knonwn places like the Himalayas and the Caribbean, but also lesser-known regions like the cerrado in Brazil, Irano-Anatolian in the Middle East and West Asia, and the Succulent Karoo in South Africa and Namibia.

“We are in a global battle for conservation, but unlike a battlefield medic, we cannot simply focus on those hotspots that are most likely to survive,” said lead author Sean Sloan also with James Cook University. “Every hotspot has unique biodiversity, so to lose even one would be catastrophic.”

Although a few other studies in the past have attempted to measure primary vegetation in biodiversity hotspots, this one far surpasses them in accuracy.

“We’ve applied a much more standardized and, we hope, rigorous approach, by using cutting-edge satellite imagery and a standardized set of criteria to define natural-intact vegetation,” Laurance told mongabay.com

Sloan, Laurance, and colleagues employed a mix of satellite imagery, Google Earth, and expert opinions to estimate vegetation at each site. The study only counted intact vegetation that covered at least 100 hectares of area.

Amount of natural intact vegetation left in the world’s biodiversity hotspots versus total area. Image by mongabay.com based on data from Sloan et al. Click to enlarge.

Moreover, according to Sloan, the vegetation needed to be “in a mature state and not in the immediate proximity to key human disturbances to the landscape, namely major roads, major and minor settlements, fires (select hotspots), and the edges of remnant vegetation fragments.” Mostly this means counting just primary forest or savannah, although mature secondary forest may be counted as well.

What they found was not heartening.

“Our estimates highlight that more hotspots than previously thought are in an extremely critical states—with [less than 5 percent] natural intact vegetation as we define it. Biodiversity in such hotspots would be highly precarious as a result, and so conservation efforts therein should be prioritized,” Sloan told mongabay.com, adding that some habitat within hotspots are “particularly devoid of natural intact vegetation, e.g., mangroves [and] seasonally dry tropical forests.”

Currently, the hotspots in most critical danger are the Atlantic Forest in Brazil, the Central Forests of Eastern Africa, the Irano-Anatolian region, Madagascar, and the Mediterranean Basin, all of which have less than five percent primary vegetation left.

Those that have lost the most vegetation since the last analysis in 2004 are the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka, the Pacific Islands, the Caucuses Mountains, the Mountains of Central Asia, Southern Africa, and Japan.

“Drier habitats such as woodlands, savannas, and grasslands are really getting hammered quickly, often by expanding agriculture,” Laurance noted. “For example, tropical dry forests are extremely vulnerable, especially in the New World. One key priority is to increase attention on these drier habitat types.”

Per its definition, not a single biodiversity hotspot maintains a majority of natural intact vegetation. In fact, the most “intact” hotspot is the California Floristic Province with just under 35 percent vegetation. The Tropical Andes, Southwest Australia, New Zealand, the Forests of Eastern Australia, the Chilean Winter Rainfall and Valdivian Forests, and the Cape Floristic Region in South Africa all have over 30 percent vegetation but just barely.

Aside from excluding well-known biodiverse wildernesses like the Amazon Basin, the Congo Rainforest, and New Guinea—due to not being threatened enough—the biodiversity hotspot concept has attracted considerable attention and funds (over $1 billion) since it’s creation over 10 years ago. Yet, much more will be needed to preserve what remains.

“We therefore renew calls for increased and targeted funding, but recognize that it will require judicious allocation as well as debate over the values underling notions of conservation ‘optimization,'” reads the paper.

But when asked which of the 35 biodiversity hotspots should be made priorities, Laurance noted, “that’s like asking someone in a sinking boat which of their children they should save!”

Madagascar is home to all of the world’s 100-plus lemurs, but the biodiversity hotspot is down to just 4.4 percent of its natural intact vegetation. Here, Verreaux’s Sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi), listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List, are in a heated chase. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Citations:

- Sloan, S., Jenkins, C.N., Joppa, L.N, Gaveau, D.L.A., Laurance, W.F. 2014. Remaining natural vegetation in the global biodiversity hotspots. Biological Conservation. 177: 12-24.

Related articles

Extinction rates are 1,000x the background rate, but it’s not all gloomy

(05/29/2014) Current extinction rates are at the high end of past predictions, according to a new paper published today in Science, however conservation efforts combined with new technologies could make a big difference. New research led by Stuart Pimm of Duke University argues that humans have pushed the current extinction rate to 1,000 times the historical rate.

‘Better late than never’: Myanmar bans timber exports to save remaining forests

(04/24/2014) Myanmar contains some of Asia’s largest forests, but has been losing them at a rapid pace during the last two decades as logging companies emptied woodlands to meet the demands of the lumber industry. In an effort to save its disappearing forests, Myanmar implemented a ban on raw timber exports, effective March 31, 2014. However, the ban affects only raw timber exports, not milled lumber, throwing into doubt its ability to adequately protect Myanmar’s forests.

(02/20/2014) Due to the wonderful idiosyncrasies of evolution, there is one country on Earth that houses 20 percent of the world’s primates. More astounding still, every single one of these primates—an entire distinct family in fact—are found no-where else. The country is, of course, Madagascar and the primates in question are, of course, lemurs. But the far-flung island of Madagascar, once a safe haven for wild evolutionary experiments, has become an ecological nightmare. Overpopulation, deep poverty, political instability, slash-and-burn agriculture, illegal logging for lucrative woods, and a booming bushmeat trade has placed 94 percent of the world’s lemurs under threat of extinction, making this the most imperiled mammal group on the planet. But, in order to stem a rapid march toward extinction, conservationists today publicized an emergency three year plan to safeguard 30 important lemur forests in the journal Science.

Scientists identify 137 protected areas most important for preserving biodiversity

(11/14/2013) Want to save the world’s biodiversity from mass extinction? Then make certain to safeguard the 74 sites identified today in a new study in Science. Evaluating 173,000 terrestrial protected areas, scientists pulled out the most important ones for global biodiversity based on the number of threatened mammals, birds, and amphibians found in the parks. In all they identified 137 protected areas (spread over 74 sites as many protected areas were in the same region) in 34 countries as ‘irreplaceable.’

‘Lost’ bird rediscovered in New Caledonia along with 16 potentially new species (photos)

(10/29/2013) In early 2011, Conservation International (CI) dubbed the forests of New Caledonia the second-most imperiled in the world after those on mainland Southeast Asia. Today, CI has released the results of a biodiversity survey under the group’s Rapid Assessment Program (RAP) to New Caledonia’s tallest mountain, Mount Panié. During the survey researchers rediscovered the ‘lost’ crow honeyeater and possibly sixteen new or recently-described species. Over 20 percent larger than Connecticut, New Caledonia is a French island east of Australia in the Pacific Ocean.

Climate change could kill off Andean cloud forests, home to thousands of species found nowhere else

(09/18/2013) One of the richest ecosystems on the planet may not survive a hotter climate without human help, according to a sobering new paper in the open source journal PLoS ONE. Although little-studied compared to lowland rainforests, the cloud forests of the Andes are known to harbor explosions of life, including thousands of species found nowhere else. Many of these species—from airy ferns to beautiful orchids to tiny frogs—thrive in small ranges that are temperature-dependent. But what happens when the climate heats up?

Scientists outline how to save nearly 70 percent of the world’s plant species

(09/05/2013) In 2010 the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) pledged to set aside 17 percent of the world’s land as protected areas in addition to protecting 60 percent of the world’s plant species—through the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC)—by 2020. Now a new study in Science finds that the world can achieve both ambitious goals at the same time—if only we protect the right places. Looking at data on over 100,000 flower plants, scientists determined that protecting 17 percent of the world’s land (focusing on priority plant areas) would conserve 67 percent of the world’s plants.

Ground zero for endangered species: new program to assist animals on the brink across Southeast Asia

(08/27/2013) Organizations within the international conservation community are joining forces to minimize impending extinctions in Southeast Asia, where habitat loss, trade and hunting have contributed to a dramatic decline in wildlife. The coalition is aptly named ASAP, or the Asian Species Action Partnership.

Trinidad and Tobago: a biodiversity hotspot overlooked

(08/26/2013) The two-island nation of Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean (just off the coast of Venezuela) may be smaller than Delaware, but it has had an outsized role in the history of rainforest conservation as well as our understanding of tropical ecology. Home to an astounding number of tropical ecosystems and over 3,000 species and counting (including 470 bird species in just 2,000 square miles), Trinidad and Tobago is an often overlooked gem in the world’s biodiversity.