Palau’s Rock Islands. Courtesy of Google Earth.

Scientists have discovered a small island bay in the Pacific which could serve as a peephole into the future of the ocean. Palau’s Rock Island Bay harbors a naturally occurring anomaly – its water is acidified as much as scientists expect the entire ocean to be by 2100 as a result of rising carbon dioxide emissions.

Surprisingly, though, the bay is home to one of the healthiest coral reefs in the Pacific. Anywhere else in the world, water acidification results in decline and death of the corals. Just not on Rock Island.

“I was shocked that coral cover, richness, and diversity were so high despite high levels of acidification,” says Katie Shamberger, one of the co-authors of a recently published research paper, which reported the unusual finding.

Ocean acidification is a well-known effect of climate change and greenhouse gas emissions. More CO2 in the atmosphere causes the ocean to absorb more carbon. This process reduces calcium carbonate in the water – the element that corals use to build their bodies. It makes them weak and prone to dissolving into the water.

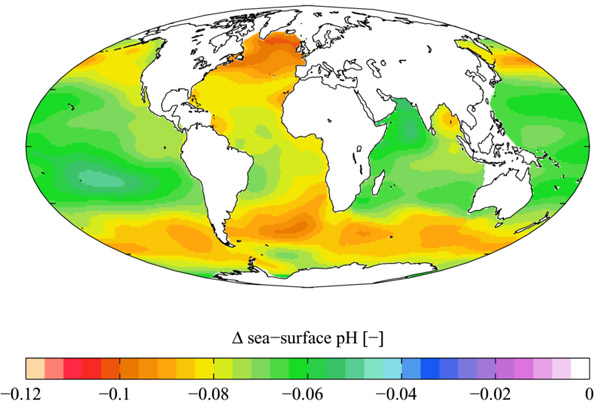

So far, the ocean’s pH (a measure of acidity) has dropped by 0.1 units since pre-industrial times, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The scientists calculated that by the end of the century, ocean’s pH might drop further down by 0.25 units below the current average.

Accidentally, that level is exactly the acidity in the Palau bay today. Yet the coral reef there is richer and healthier than all reefs in other naturally occurring high acidity coastal regions in Papua New Guinea, Galapagos, Gulf of Panama and Yukatan peninsula. Why are the corals in Rock Island the only ones not affected by the acidified water?

“We don’t know,” admits Shamberger. Possibly after growing in this bay for thousands of years, they genetically adapted to high level of acidification. Or there might be some combination of environmental factors that allows them to survive despite the acidification.

“The critical point is that Palau’s acidified reefs are an exception,” says Shamberger. “This does not mean that coral reefs in general will be able to handle ocean acidification.”

Even if genetic adaptation to high water acidity is possible, the coral reefs in the Rock Island probably had thousands of years to achieve it. Today ocean acidification is happening much too quickly: other reefs will have less than 100 years to try to adjust.

Unfortunately, this is not the only threat climate change presents to coral reefs. Warmer seawater can kill the algae living inside the coral skeleton, which provide nutrition for the corals. With their death, the corals loose both their food source and their color, hence the process is called coral bleaching. Sometimes corals can recover from bleaching but if the water stays too warm for too long it can cause them to die.

Finally, coral reefs need a lot of light for their algae so they need to be near the surface. If corals cannot grow vertically fast enough to keep up with sea level rise, they can actually “drown” – die from being too deep and not getting enough light.

“Climate change is a triple threat to corals,” says Shamberger. “Warming, acidification, and sea level rise all threaten coral reefs.”

Changes in oceanic pH levels from 1700 to the 1990s. Image by: Plumbago/Creative Commons 3.0.

CITATION: Kathryn Shamberger, Anne Cohen, Yimnang Golbuu, Daniel McCorkle, Steven Lentz, Hannah Barkley (2013) Diverse coral communities in naturally acidified waters of a Western Pacific reef. Geophysical Research Letters.

Related articles