One of the world’s least-known flying foxes could face extinction by rising seas and changing precipitation patterns due to global warming, according to a new study in Zookeys. The research, headed by Donald Buden with the College of Micronesia, is the first in-depth study of the resident bats of the remote Mortlock Islands, a part of the Federated States of Micronesia.

Currently considered Critically Endangered, the bats, known as Chuuk flying foxes (Pteropus pelagicus), were threatened by commercial hunting for export in the late Twentieth Century. However, international protection appears to have helped the species stabilize. According to the first ever formal survey, Buden and his team estimated around 900 to 1,200 bats surviving on the tiny, low-lying Mortlock islands.

Another important discovery has boosted the population even more, however. After careful study, Buden and his team contend that the flying foxes on the Mortlock Islands are the same species as those found on nearby Chuuk Lagoon islands (though a different subspecies). This essentially expands the range of the species and raises hopes that the species can avoid extinction.

However, that may well depend on how quickly humans take action to mitigate climate change.

“For those bats inhabiting the Mortlocks and other low lying coralline islands, which are barely above sea level, there will likely be a major negative impact [from global warming]. Aside from the loss of land on islands that are already very small in size, sea water encroachment into the water table along with more frequent total or near total inundation of the islands during storm surges would eliminate the food and roosting sites on which the bats currently depend,” Buden told mongabay.com.

Painting of Pteropus pelagicus (notice the name change). |

Still, the fact that the species is also found on the volcanic Chuuk Lagoon islands—many of which rise high above sea level—may safeguard the species from total extinction.

“But to what extent changing weather patterns [under climate change] will affect vegetation type and food resources is not certain,” explains Buden. Given these ongoing threats, he suggests the species should be considered “at least Vulnerable if not actually Endangered.”

The researchers also studied the behavior of the Mortlock Islands’ bats and found that these populations appear to breed year-round, as opposed to most other flying fox species that have distinct breeding periods. Buden also suspects that they play a role in seed dispersal, but this wasn’t studied during the research.

Buden and his team uncovered one final surprise: the bats were actually discovered by science fifty years before believed. The team found a manuscript by German naturalist F.H. Kittlitz who visited the islands in the 1820s and named the bats Pteropus pelagicus, beating British biologist Oldfield Thomas who named the bats a second time in 1870 (not having known about Kittlitz’s voyage). The discovery means that Kittlitz’s name of Pteropus pelagicus has priority since it came first, and strikes Oldfield’s later name Pteropus phaeocephalus from the record.

“This remarkable study shows how much we have to learn about Pacific Islands mammals,” commented Tim Flannery of Macquarie University in Sydney, who was not involved in the research. “Where there was darkness, Dr. Buden and colleagues have shed light.”

Flying foxes (in the genus Pteropus) are the largest bats in the world. With around 60 known species, they are found only in the tropics, including Asia, Australia, the Pacific and Indian Ocean.

Bats, generally, receive less conservation and research attention than most of the world’s other mammals, despite the fact that they make up about 20 percent of the world’s mammals and many are on the edge of extinction. In fact, one of the most recently confirmed mammalian extinctions was the Christmas Island pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi), which scientists believed vanished forever in 2009.

Few clear photos exist of Pteropus pelagicus. This is the flying fox on Oneop Island a part of the Mortlock Islands chain. Photo by: Danko Taborosi.

Pteropus pelagicus that the photographer found in his kitchen on Oneop Island. Photo by: Naavid Khatibi.

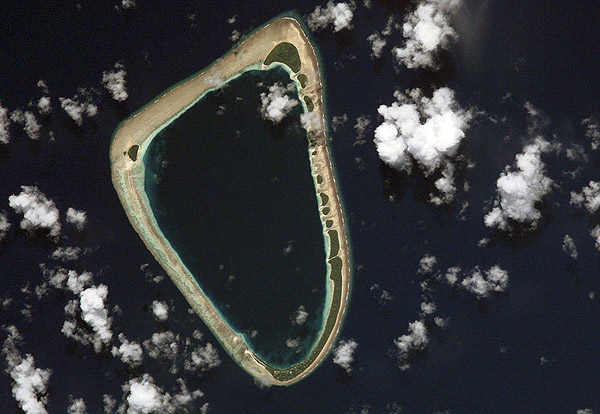

Sattelite image of Ettal Atoll, an island in the Mortlock Islands and home to Pteropus pelagicus. Photo by: NASA.

Citations:

- Buden D W, Helgen KM, Wiles GJ (2013) Taxonomy, distribution, and natural history of flying foxes (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) in the Mortlock Islands and Chuuk State, Caroline Islands. ZooKeys xxx

Related articles

President’s pledge to ban commercial fishing around Pacific island nation slow to materialize

(09/23/2013) In 2010 President Anote Tong of Kiribati made a historic pledge, committing to protect the waters around his island nation in a massive marine protected area. He said the gesture represented Kiribati’s contribution to protecting the environment and he urged industrial countries to do the same by cutting their greenhouse gas emissions, which threaten low-lying islands with rising sea levels. The commitment raised Tong’s profile, winning him international accolades, and boosted the tiny country’s standing in the fight against climate change. But since 2010 questions have begun to emerge about the extent of Tong’s commitment.

Solomon Islands’ banks shut down logging company accounts

(08/16/2013) Banks in the Solomon Islands have shut down bank accounts belonging to several foreign logging companies.

Logging endangers UNESCO World Heritage Site in Solomon Islands

(06/22/2013) A world heritage site in the Solomon Islands is ‘in danger’ due to logging, warns the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

(05/15/2013) With islands and atolls scattered across the ocean, the small Pacific island states are among those most exposed to the effects of global warming: increasing acidity and rising sea level, more frequent natural disasters and damage to coral reefs. These micro-states, home to about 10 million people, are already paying for the environmental irresponsibility of the great powers.

Industrialized fishing has forced seabirds to change what they eat

(05/14/2013) The bleached bones of seabirds are telling us a new story about the far-reaching impacts of industrial fisheries on today’s oceans. Looking at the isotopes of 250 bones from Hawaiian petrels (Pterodroma sandwichensis), scientists have been able to reconstruct the birds’ diets over the last 3,000 years. They found an unmistakable shift from big prey to small prey around 100 years ago, just when large, modern fisheries started scooping up fish at never before seen rates. The dietary shift shows that modern fisheries upended predator and prey relationships even in the ocean ocean and have possibly played a role in the decline of some seabirds.