Call recognition for animals.

New technology makes it possible to automatically identify species by their vocalizations.

The software and hardware system, detailed in the current issue of the journal PeerJ, has been used at sites in Puerto Rico and Costa Rica to identify frogs, insects, birds, and monkeys. Many of the animals identified by the system are typically difficult to spot in their natural environment, but audio recordings of their calls reveal not only their presence but also their activity patterns. The platform, which is called the Automated Remote Biodiversity Monitoring Network (ARBIMON), could potentially allow scientists to monitor species in remote sites without having a physical presence on the ground, according to the study’s lead author Mitchell Aide of the University of Puerto Rico.

“To understand the impacts of deforestation and climate change, we need reliable long-term data on the fauna from around the world,” Aide said. “Traditional sampling methodology, sending biologists to the field, is expensive and often results in incomplete and limited data sets because it is impossible to maintain biologists in the field 24 hours a day throughout the year, and it is impossible to clone expert field biologists, so that they can monitor various sites simultaneously.”

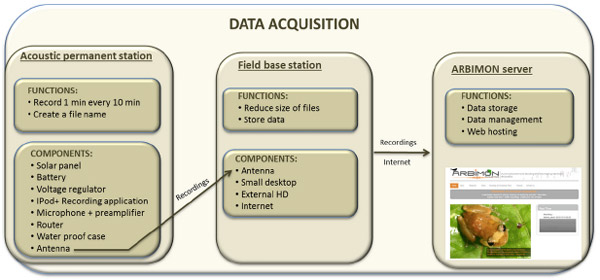

The data acquisition phase of ARBIMON. Courtesy of Aide et al. (2013).

Study co-author Carlos Corrada-Bravo, also of the University of Puerto Rico, says the technology enables experts to leverage their knowledge and test hypotheses on a broader scale in the field.

“We are not trying to eliminate the biologist,” said Corrada-Bravo. “On the contrary, we are trying to provide the best data and tools possible, so that the biologists can use their time to convert these data into useful information for science, conservation, management, and education.”

Corrada-Bravo added that because the data is stored for perpetuity in an online repository, it can be used by future generations of scientists.

“Each recording is the equivalent of a museum sample, which can be analyzed with the knowledge and technologies we have today, but which will be permanently stored so that biologists 20 or 50 years from now, will be able to analyze these recordings with new technologies and ideas.”

The call of the strawberry dart frog (Oophaga pumilio) was detected with 100 percent accuracy during the field tests at La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica. Photo taken by Rhett A. Butler in June 2013.

ARBIMON utilizes both software and hardware, including a solar powered remote monitoring station. A statement from the University of Puerto Rico explains:

-

The hardware, which utilizes cheap and easily obtainable components such as iPods and car batteries, records 144 one-minute recordings per day in remote sites and sends them in real-time to a base station up to 40 km away. The recordings are then forwarded to the project server in Puerto Rico where they are processed and made available to the world through the internet in less than a minute. The system was tested in Puerto Rico and Costa Rica, and today, anyone with an internet connection can view and listen to more than 1 million recordings from these and many other sites such as Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Arizona, Costa Rica, Argentina, and Brazil (via http://arbimon.com). To automate species identification, the group developed a web application which provides users with tools to train the software to automate species identification, along with other tools for measuring the accuracy and precision of the model. Once the biologist has developed a reliable model, the computer can process more than 100,000 recordings in less than an hour, providing information on species presence and absence.

ARBIMON could potentially augment other emerging conservation-oriented technologies. For example, Rainforest Connection, a San Francisco-based organization working in the Sumatran rainforest, recently installed units that listen for gunshots and chainsaws. Any noises that match those audio signatures trigger an alert that is relayed to a local authority, enabling real-time enforcement action. Rainforest Connection’s units, which are built from used Android phones, could be tuned to listen for specific animal calls — even warning vocalizations that could signal a poaching threat.

“ARBIMON’s commitment to openness is truly exciting,” Rainforest Connection founder Topher White told mongabay.com. “In the future, the data generated by our units could potentially be integrated with ARBIMON’s library for a given region, allowing us to track animal alarm calls, and help authorities to intervene in wildlife poaching in real-time.”

Meanwhile, Conservation Drones, which combine mapping software with specially-outfitted model airplanes and helicopters, are being used for a range of applications, including monitoring, data collection, high resolution mapping. Lian Pin Koh, a researcher who has pioneered conservation drone development in recent years, says a drone’s ability to deliver payload to remote areas might have some utility for ARBIMON.

“A miniaturized version of the ARBIMON system could be delivered by a drone to inaccessible parts of the forest for monitoring animal calls,” Koh told mongabay.com.

The chestnut-mandibled toucan (Ramphastos swainsonii) is one of the species that was detected in the field tests at La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica. Photo taken by Rhett A. Butler in June 2013.

The ARBIMON study authors agree that new technologies will play a critical role in improving conservation efforts.

“These web-based tools greatly simplify the process of extracting useful results for researchers and managers from the raw data (i.e., recordings), which should help the users to improve and expand their ecological monitoring programs,” they write.

In the end, the goal for these new tools is to craft better protections for the world’s imperiled wildlife and place.

“Conserving and managing the biodiversity in the world is a major challenge for society, particularly in the tropics,” said Aide. “We hope that the tools we have developed will allow researchers, students, managers, and the public to better understand how these threats are impacting species, so that we can make informed conservation and management decisions.”

CITATION: Aide et al. (2013). Real-time bioacoustics monitoring and automated species identification. PeerJ 1:e103; DOI 10.7717/peerj.103

Related articles

New forensic method tells the difference between poached and legal ivory

(07/01/2013) Forensic-dating could end a major loophole in the current global ban on ivory, according to a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Scientists have developed a method to determine the age of ivory, allowing traders to tell the difference between ivory taken before the ban in 1989, which is still legal, and recently-poached ivory.

A new tool against illegal logging: tree DNA technology goes mainstream

(04/22/2013) Modern DNA technology offers a unique opportunity: you could pinpoint the origin of your table at home and track down if the trees it was made from were illegally obtained. Each wooden piece of furniture comes with a hidden natural barcode that can tell its story from a sapling in a forest all the way to your living room.

Conservation gets boost from new Landsat satellite

(04/03/2013) Efforts to monitor the world’s forests and other ecosystems got a big boost in February with the launch of Landsat 8, NASA’s newest earth observation satellite, which augments the crippled Landsat 7 currently orbiting Earth (technically Landsat 8 is still named the Landsat Data Continuity Mission (LDCM) and will remain so until May when the USGS turns control of the satellite over to NASA). Landsat 8/LDCM is the most advanced Earth observation satellite to date. It is the eighth Landsat since the initial launch in 1972.

Frogs radio-tracked for first time in Madagascar

![]()

(03/01/2013) Researchers have radio-tracked frogs for the first time in Madagascar. Attaching tiny radio transmitters weighing 0.3-0.35 grams (1/100 of an ounce) to 36 rainbow frogs (Scaphiophryne gottlebei), the research team tracked the movement of the colorful frogs through rugged canyons in Madagascar’s Isalo Massif. They found that the frogs have a short breeding period that occurs after the first intense rainfall at the start of the rainy season.

Illegally logged trees to start calling for help

(01/24/2013) Illegal loggers beware: trees will soon be calling—literally—for backup. The Brazilian government has begun fixing trees with a wireless device, known as Invisible Tracck, which will allow trees to contact authorities after being felled and moved.

Bloodsucking flies help scientists identify rare, hard-to-find mammals

(01/16/2013) Last year scientists released a study that is likely to revolutionize how conservationists track elusive species. Researchers extracted the recently sucked blood of terrestrial leeches in Vietnam’s remote Annamite Mountains and looked at the DNA of what they’d been feeding on: remarkably researchers were able to identify a number of endangered and rarely-seen mammals. In fact two of the species gleaned from these blood-meals had been discovered by scientists as late as the 1990s. In the past, trying to find rare and shy jungle animals required many man hours and a lot of funding. While the increasing use of remote camera traps has allowed scientists to expand their search, DNA sampling from leeches could be the next big step in simplifying (and cheapening) the quest for tracking the world’s mammals.

Cell phones help decipher malaria transmission in Kenya

(11/19/2012) Malaria parasites can stow away silently in a person’s bloodstream. Without any symptoms to betray them, their human host can unwittingly transport the parasites hundreds or thousands of miles. Tracking them has been nearly impossible, especially in poor countries. Now, researchers have harnessed a new tool: the burgeoning number of cell phone users in Africa, which help trace how malaria spreads.

Conservationists turn camera traps on tiger poachers

(11/12/2012) Remote camera traps, which take photos or video when a sensor is triggered, have been increasingly used to document rare and shy wildlife, but now conservationists are taking the technology one step further: detecting poachers. Already, camera traps set up for wildlife have captured images of park trespassers and poachers worldwide, but for the first time conservationists are setting camera traps with the specific goal of tracking illegal activity.

Remote-controlled model planes offer bird’s-eye approach to conservation

(07/10/2012) Inexpensive aerial drones can help conservationists map forests, monitor land use change like deforestation, and track wildlife in remote and inaccessible areas, reports a new study published in the journal Tropical Conservation Science.

Model airplane used to monitor rainforests – conservation drones take flight

(02/23/2012) Conservationists have converted a remote-controlled plane into a potent tool for conservation. Using seed funding from the National Geographic Society, The Orangutan Conservancy, and the Denver Zoo, Lian Pin Koh, an ecologist at the ETH Zürich, and Serge Wich, a biologist at the University of Zürich and PanEco, have developed a conservation drone equipped with cameras, sensors and GPS. So far they have used the remote-controlled aircraft to map deforestation, count orangutans and other endangered species, and get a bird’s eye view of hard-to-access forest areas in North Sumatra, Indonesia.

The camera trap revolution: how a simple device is shaping research and conservation worldwide

.150.jpg)

(02/14/2012) I must confess to a recent addiction: camera trap photos. When the Smithsonian released 202,000 camera trap photos to the public online, I couldn’t help but spend hours transfixed by the private world of animals. There was the golden snub-monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana), with its unmistakably blue face staring straight at you, captured on a trail in the mountains of China. Or a southern tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla), a tree anteater that resembles a living Muppet, poking its nose in the leaf litter as sunlight plays on its head in the Peruvian Amazon. Or the dim body of a spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) led by jewel-like eyes in the Tanzanian night. Or the less exotic red fox (Vulpes vulpes) which admittedly appears much more exotic when shot in China in the midst of a snowstorm. Even the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), an animal I too often connect with cartoons and stuffed animals, looks wholly real and wild when captured by camera trap: no longer a symbol or even a pudgy bear at the zoo, but a true animal with its own inner, mysterious life.

Breakthrough technology enables 3D mapping of rainforests, tree by tree

(10/24/2011) High above the Amazon rainforest in Peru, a team of scientists and technicians is conducting an ambitious experiment: a biological survey of a never-before-explored tract of remote and inaccessible cloud forest. They are doing so using an advanced system that enables them to map the three-dimensional physical structure of the forest as well as its chemical and optical properties. The scientists hope to determine not only what species may lie below but also how the ecosystem is responding to last year’s drought—the worst ever recorded in the Amazon—as well as help Peru develop a better mechanism for monitoring deforestation and degradation.