Greenpeace and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a body that sets criteria for greener palm oil production, are caught up in a row over the origin of fires that cast a pall over Sumatra, Singapore, and Malaysia last month.

The dispute started when media outlets, based on independent analysis of satellite data, identified several members of the RSPO as possible culprits in the fires in Riau Province. Greenpeace said the findings indicated that the RSPO is failing to hold its members accountable for burning. The activist group also criticized the RSPO for not expressly prohibiting deforestation and conversion of peatlands.

The RSPO responded by demanding that five member companies named in media reports submit maps of their concessions to prove that they were not involved in burning. Four of those five companies — Sime Darby, Kuala Lumpur Kepong (KLK), Golden Agri Resources (GAR), and Tabung Haji Plantations — complied with the demand. The fifth, PT Jatim Jaya Perkasa, missed the deadline, but filed the coordinates of its concessions on July 10.

The RSPO then handed the shape files showing the coordinates of the companies’ oil palm concessions over to the World Resources Institute (WRI) and Khali Aziz Hamzah, a GIS expert at the Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM), for analysis. The analysis, published July 11, revealed only a handful of hotspots in the plantation areas for Sime Darby, GAR, and Sime Darby. Jatim Jaya Perkasa had 74 hotspots, according to a statement issued by the RSPO on July 15.

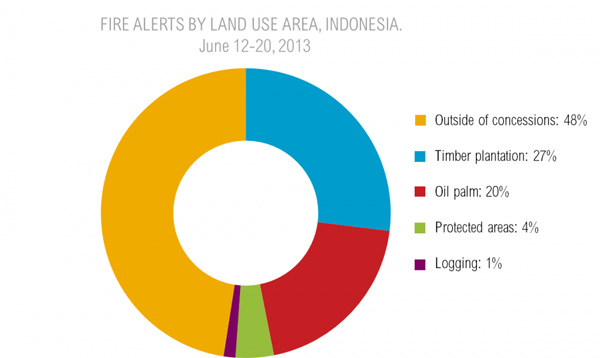

WRI analysis showing fire hotspot alerts by land use in Sumatra, June 2013.

Greenpeace however wasn’t satisfied with those results, issuing a statement that those companies weren’t the ones with the most fire hotspots and that RSPO’s analysis glossed over the underlying issue: decades of forest clearance and peatlands drainage that set the stage for the most recent fires.

“The RSPO decided to focus its own investigations on just five of its members, but Greenpeace’s evidence points to a far wider problem for the sector, which neither the RSPO nor the companies implicated are owning up to,” said Bustar Maitar, head of the Indonesia Forest Campaign at Greenpeace International, in a statement issued July 11. “Rather than claiming the innocence of members who’ve been reported in the media, the RSPO needs to address the real problem – years of peatland drainage and destruction which is labeled ‘sustainable’ under RSPO rules and has laid the foundation for these disastrous fires.”

“The RSPO was established nearly a decade ago in the wake of the 1997 forest fires, yet to date, it has failed to tackle its members’ role in creating the conditions that lead to such disaster, nor has it held companies accountable for the impact of their operations. It’s time for individual palm oil companies to step up and set the bar higher than the RSPO.”

An excavator creates a canal in Riau Province, Indonesia, despite the heavy smoke caused by the forest fires. © Ulet Ifansasti / Greenpeace

But the RSPO didn’t take that response lightly, issuing a statement that directly confronted Greenpeace on an issue that some Indonesian NGOs have been whispering about for weeks: Greenpeace’s apparent lack of interest in focusing on hotspots detected within concessions belonging to Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) and its affiliates. APP is currently working to implement a “zero-deforestation” policy across the forest products giant’s entire supply chain.

“The RSPO is of the opinion that Greenpeace has misplaced its objectivity in its analysis of the fires in Sumatra, Indonesia. It has been reported that the palm oil sector has contributed to 20% of the recent fires in Sumatra. Out of the many companies implicated, less than a handful of these companies are RSPO members – which the RSPO views as serious and is fully committed to investigating and taking appropriate action if verified,” said the RSPO in a statement posted July 15.

“However, at its peak there were 9000 hotspots identified and that 80% of the fires are occurring outside of palm oil plantations. The pulp and paper plantations have been identified as having significantly more fires than the oil palm plantations. This is a sector that Greenpeace has been actively involved in and we hope that Greenpeace would regain some perspective and start to apply the same rigor of watchfulness in this sector that the RSPO has in undertaking its own investigations.”

The RSPO also criticized Greenpeace for using the media, rather than the body’s complaint process, for alleging violations of standards.

“The RSPO has systems in place for stakeholders to seek recourse for any alleged violation against its code of conduct. On the other hand – Greenpeace has considerable resources, on the ground, which can provide credible evidence to make it easier for stakeholders to seek such recourse. It therefore would be highly constructive if Greenpeace and the RSPO can collaborate to address the issue at hand rather than using media sensationalism to address such a critical environmental dilemma.”

Greenpeace subsequently responded saying the RSPO needs to be held accountable the role its member companies have played in creating conditions for fires.

“The RSPO cannot wash its hands of any responsibility for helping create the conditions in which the terrible fires last month took hold,” Maitar told mongabay.com.

“The widespread drainage and clearance of peatland by plantation companies lays the conditions for the fires to turn into the disaster we all witnessed last month. Despite the RSPO’s public status as a champion of sustainability it still has not banned its members from deforesting or developing on peatland. Until it does, it implicitly gives a green stamp to dirty palm oil operations that set the stage for future fires.”

WRI analysis showing fire hotspot alerts by land cover in Sumatra, June 2013.

The dispute between Greenpeace and RSPO risks shifting the focus away from other actors and issues associated with the haze. For example, while subsistence slash-and-burn farmers and industrial plantation developers have been mostly blamed for the recent fires, a new study by the World Agroforestry Centre suggests that a third category of land users — ‘mid-level entrepreneurs’ — may be in part responsible for the haze.

“These people acquire land under informal rules at village level, effectively sidestepping the Government land-use system,” explained a statement from the World Agroforestry Centre. “They bring in their own labour to clear the land for oil palm, regardless of the land’s formal government status and in the absence of any permits to do so.”

Discrepancies between boundary maps for a concession held by the Sime Darby palm oil company made available to WRI. Sime Darby’s self-reported boundaries represent the Business Use Rights License (known in Indonesia as a Hak Guna Usaha or “HGU” license), but there is great discrepancy between the national government concession boundaries (even between 2010 and 2013) and the license information provided by the company. Courtesy of WRI.

On a more formal level, the response to the haze reveals that the Indonesian government has also failed to maintain, and make available, accurate data on concession ownership, complicating efforts to control fires and take action against those who started fires. And burning outside concession areas has effectively set the stage for the next round of concession expansion. It’s unclear whether the government has the monitoring and enforcement systems in place to ensure that those who set the fires areas won’t benefit from their illegal activities.

Finally while various parties are trying to assign blame for the haze, the fire risk in Riau has not diminished appreciably. WRI, which has been tracking fires closely, says “it is highly likely that severe burning seasons like the one we have seen over the past several weeks will be repeated.”

“Forest fires in Indonesia are part of a long-standing, endemic problem—one that needs a coordinated and comprehensive solution if fire and haze risks are to be reduced.”

Related articles