University at Buffalo students crawl over remnants of an ancient glacier on Baffin Island, Canada. Photo by Jason Briner, courtesy of the University at Buffalo.

Even as glaciers retreat from rising temperatures worldwide, new research says they could bounce back just as suddenly.

The study, published Sept. 14 in Science, shows that both small mountain glaciers and large ice sheets grew considerably during a short, 150-year cold spell in Canada 8,200 years ago. The results suggest that massive ice sheets are surprisingly sensitive to brief shifts in seasonal temperatures.

Glaciologists had thought that ice sheets, such as Greenland’s and Antarctica’s, responded slowly to climate change, building up or eroding over thousands of years. Smaller isolated mountain glaciers, which depend on a steady supply of winter snow, could react more quickly. Mountain glaciers are made up of decades’ worth of snow that coalesce into ice and start creeping downhill, like hot taffy. Ice sheet glaciers are tongues of ice squeezed out of the margins of a massive parent ice sheet.

A team based at the University at Buffalo studied remnants of both glaciers and ice sheets on Canada’s Baffin Island, which neighbors Greenland. They compared how ice grew during an ancient cool-down known, awkwardly, as “the 8.2-ka event” (ka stands for kiloannum, or thousand years ago). Average temperatures then were three to four degrees Celsius colder than today’s.

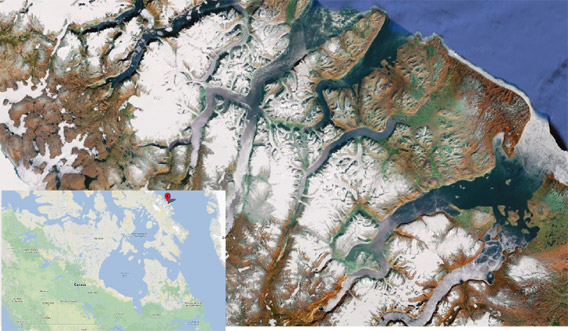

Glacial valley on Baffin Island, Canada, site of ancient glacial moraines. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

The team, led by Nicolás Young, now at Columbia University, measured the ages of piles of rock and debris, called “end moraines,” to determine how large the glaciers grew at different times. The “snout” of a glacier piles up end moraines during its incessant advance, scraping rocks and dirt like a bulldozer’s blade.

Glaciers are relentless rivers of ice, constantly moving forward. Glaciers that melt faster than they move appear to be retreating. When glaciers retreat, they leave behind moraines like high-water marks. But if the weather turns cooler, as in the 8.2-ka event, the glaciers will melt less and start to advance again.

Young found that glaciers of all sizes on Baffin Island began to grow during the short cooling event. Both the continental ice sheet in Canada and smaller local glaciers grew at about the same time.

“Many folks may say, ‘All you have shown is that when it got cold the ice sheet grew—that doesn’t sound interesting,’” Young told mongabay.com. Quick growth, he said, wouldn’t be surprising for a mountain glacier. “But for an ice sheet to do this, it tells us that ice sheets are perhaps more sensitive to short-term temperature change than we previously thought.”

Other scientists support the team’s conclusions. “They make a convincing case that you’re getting the two systems responding about the same time,” said Gifford Miller, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, in an interview with mongabay.com. Past responses to abrupt temperature swings, Miller said, helps scientists understand how climate affects Earth’s surface.

Cooler summers, not colder winters, spurred the ice build-up, the team concluded. Baffin Island glaciers were larger during the 8.2-ka event than during the Younger Dryas, a colder, longer cooling trend 4,000 years earlier. The difference? The Younger Dryas had cold winters, while the 8.2-ka event had cool summers.

This rapid response to changing climate applies during warming trends as well, Young noted. “There is some hope,” he said. “If we change our ways, we might be able to at least slow the rate of Greenland Ice Sheet melt.”

CITATION: Young, N. E., Briner, J. P., Rood, D. H., & Finkel, R. C. Glacier Extent During the Younger Dryas and 8.2-ka Event on Baffin Island, Arctic Canada. Science, 14 September 2012. DOI: 10.1126/science.1222759.

Paul Gabrielsen is a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Related articles