Since 1898 North America has lost at least 39 species of freshwater fish, according to a new study in Bioscience, and an additional 18 subspecies. Moreover, the loss of freshwater fish on the continent seems to be increasing, as the rate jumped by 25 percent since 1989, though even this data may be low.

“Estimates of freshwater fish extinctions during the twentieth century are conservative, because it can take 20-50 years to confirm extinction,” explains lead author, Noel Burkhead, a research fish biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), in a press release.

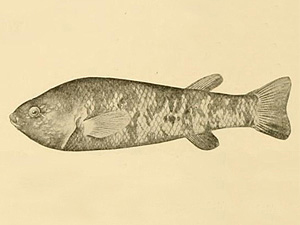

Depiction of an Ash Meadows killifish (Empetrichthys merriami) which went extinct in the 1950s. Image by: David Starr Jordan. |

Burkhead calculated that the rate of freshwater fish extinction on the continent is at least 877 times faster than in the fossil record, where a freshwater fish vanished every 3 million years or so on average. Currently, 1,213 freshwater fish are found in Northern America.

Over the last century fish have been pushed to extinction by dams, pollution, invasive species, channelization of rivers, and other impacts. But as bad as fish have it, freshwater snails and mussels are going extinct at even quicker rates.

Worldwide, freshwater species are more imperiled than other groups. A scientist in 2009 calculated that freshwater species were currently four to six more likely to go extinct than their marine and land relatives. For decades, scientists have warned that the Earth may soon, or already, be facing a mass extinction due to human impacts.

Related articles

Climate change may be worsening impacts of killer frog disease

(08/13/2012) Climate change, which is spawning more extreme temperatures variations worldwide, may be worsening the effects of a devastating fungal disease on the world’s amphibians, according to new research published in Nature Climate Change. Researchers found that frogs infected with the disease, known as chytridiomycosis, perished more rapidly when temperatures swung wildly. However scientists told the BBC that more research is needed before any definitive link between climate change and chytridiomycosis mortalities could be made.

Still time to save most species in the Brazilian Amazon

(07/12/2012) Once habitat is lost or degraded, a species doesn’t just wink out of existence: it takes time, often several generations, before a species vanishes for good. A new study in Science investigates this process, called “extinction debt”, in the Brazilian Amazon and finds that 80-90 percent of the predicted extinctions of birds, amphibians, and mammals have not yet occurred. But, unless urgent action is taken, the debt will be collected, and these species will vanish for good in the next few decades.

Meet the world’s rarest snake: only 18 left

-(Large).150.jpg)

(07/10/2012) It’s slithery, brown, and doesn’t mind being picked up: meet the Saint Lucia racer (Liophis ornatus), which holds the dubious honor of being the world’s most endangered snake. A five month extensive survey found just 18 animals on a small islet off of the Caribbean Island of Saint Lucia. The snake had once been abundant on Saint Lucia, as well, but was decimated by invasive mongooses. For nearly 40 years the snake was thought to be extinct until in 1973 a single snake was found on the Maria Major Island, a 12-hectare (30 acre) protected islet, a mile off the coast of Saint Lucia (see map below).

With the death of the world’s rarest creature, ranger loses his best friend, Lonesome George

(06/29/2012) With the death of Lonesome George, the world lost the last member of a subspecies and Ecuador its greatest symbol of the Galapagos Islands, but Fausto Llerena lost his best friend.

96 percent of the world’s species remain unevaluated by the Red List

(06/28/2012) Nearly 250 species have been added to the threatened categories—i.e. Vulnerable, Endangered, and Critically Endangered—in this year’s update of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List. The 247 additions—including sixty bird species—pushes the number of threatened species globally perilously close to 20,000. However to date the Red List has only assessed 4 percent of the world’s known species; for the other 96 percent, scientists simply don’t know how they are faring.