Mining has often been associated with conflict in Colombia, which is one of the world’s most diverse countries in terms of wildlife, plants, and cultures. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

Colombia’s move last week to begin granting new mining concessions across 17.6 million hectares has raised concerns about the potential environmental impacts of a new mining boom across the country.

Colombia’s rich mineral deposits have long been eyed by investors, but civil conflict limited extraction to secure areas until the early to mid 2000s. With the decline in violence in recent years, mining projects in the country have mushroomed, including a surge in unlicensed and unregulated wildcat mines — the National Mining Agency said yesterday that a census for 2010-2011 found that 73 percent of mining operations lack proper title.

But with the influx of miners, there have been rising complaints about environmental damage. Earlier this month environmentalists held demonstrations demanding stronger safeguards in a new mining code that will be submitted to Congress next year. Meanwhile indigenous groups have been reporting conflict with both large mining companies and small-scale miners for years.

The Colombian government asserts that despite opening vast areas for mining, including regions renowned for their high levels of biodiversity, the new mining regulation will limit some of the worst damage seen in recent years by formalizing small-scale miners. It says the new mining code will prohibit mining in protected areas and sensitive ecosystems.

Gold mining in Peru, which like Colombia, is experiencing a mining boom. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

Environmentalists aren’t so sure. According to Catherine Gamba-Trimiño, an independent environmental consultant, mining titles and environmental licenses already granted in protected areas would be allowed to stand, while lower-level protected areas, like civil society nature reserves and municipal parks wouldn’t be off-limits.

“Governmental efforts to plan and organize development and extractive activities are applauded,” Gamba-Trimiño told mongabay.com. “However, asking Colombian society to pay the price for the environmental licenses already granted in strategic ecosystems such as paramos, instead of perhaps indemnifying companies and revoking former licenses, is not fair.”

Gamba-Trimiño added that indigenous communities — which control large swathes of Colombia, including areas being targeted for mining — may also lose out under the new rules.

“Companies are obliged to consult only with Indigenous and Afro-Colombians before starting operations in their lands, but the Mining and Energy Minister has been clear at saying ‘they have no veto power.'”

Related articles

Nintendo is ‘worst’ company on conflict minerals

(08/16/2012) Gaming giant Nintendo is the worst company for ensuring that materials used in its electronics are not linked to bloodshed in war-torn regions like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), according to an assessment released today by the Enough Project, an initiative that aims to boost transparency around minerals sourcing.

Peru considers big changes to its environmental reviews

(08/01/2012) The Peruvian government is looking into making large-scale changes to its Environment Impact Assessments (EIA) after a review found significant problems with the vast majority of past reviews, reports the Inter Press Service. The news comes a few weeks after protests over a proposed gold and copper mine in the Andes left five people dead, including a 17-year-old boy.

Over 700 people killed defending forest and land rights in past ten years

(06/19/2012) On May 24th, 2011, forest activist José Cláudio Ribeiro da Silva and his wife, Maria do Espírito Santo da Silva, were gunned down in an ambush in the Brazilian state of Pará. A longtime activist, José Cláudio Ribeiro da Silva had made a name for himself for openly criticizing illegal logging in the state which is rife with deforestation. The killers even cut off the ears of the da Silvas, a common practice of assassins in Brazil to prove to their employers that they had committed the deed. Less than a year before he was murdered, da Silva warned in a TEDx Talk, “I could get a bullet in my head at any moment…because I denounce the loggers and charcoal producers.”

Gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon: a view from the ground

(03/15/2012) On the back of a partially functioning motorcycle I fly down miles of winding footpath at high-speed through the dense Amazon rainforest, the driver never able to see more than several feet ahead. Myriads of bizarre creatures lie camouflaged amongst the dense vines and lush foliage; flocks of parrots fly overhead in rainbows of color; a moss-covered three-toed sloth dangles from an overhanging branch; a troop of red howler monkeys rumble continuously in the background; leafcutter ants form miles of crawling highways across the forest floor. Even the hot, wet air feels alive.

Cultural erosion among indigenous groups in Venezuela brings new risks for Caura rainforest

(11/14/2011) One of the planet’s most beautiful landscapes is in danger. Deep in southern Venezuela, among ancient forested tabletop mountains known as tepuis, crystalline rivers, and breathtaking waterfalls, outside influences — malaria, the high price of gold, commercial hunting, and cultural erosion — are threatening one of world’s largest remaining blocks of wilderness, one that is home to indigenous people and strikingly high levels of biological diversity.

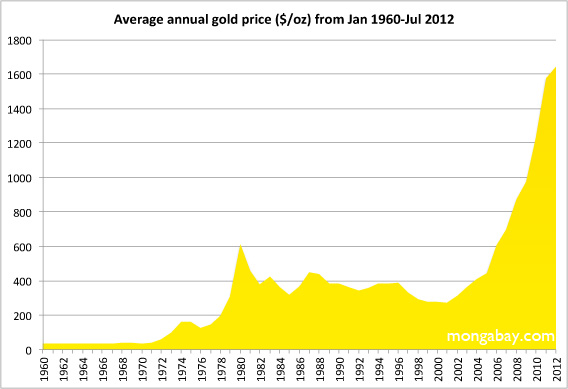

High gold price triggers rainforest devastation in Peru

(10/11/2011) As the price of gold inches upward on international markets, a dead zone is spreading across the southern Peruvian rain forest. Tourists flying to Manu or Tambopata, the crown jewels of the country’s Amazonian parks, get a jarring view of a muddy, cratered moonscape … and then another … and another in what the country boasts is its capital of biodiversity. While alluvial gold mining in the Amazon is probably older than the Incas, miners using motorized suction equipment, huge floating dredges and backhoes are plowing through the landscape on an unprecedented scale, leaving treeless scars visible from outer space. Sources close to the Peruvian Environment Ministry say the government is considering declaring an environmental emergency in the region, but emergency measures passed two years ago were not enough to contain the destruction, and some observers doubt that a new decree would have any more impact.