Indigenous protest in Sarawak. Image courtesy of The Borneo Project.

In the 1980s images of loincloth-clad tribesmen blockading blockading logging roads in Malaysian Borneo shocked the world. But while their protests captured the spotlight momentarily, Borneo’s forests continued to be destroyed at rapid rates, undermining traditional communities that are dependent on these ecosystems for food, shelter, medicine, clean water, and spiritual inspiration.

Nomadic tribes are now but a memory in Borneo, but other tribal groups continue to fight for their forests by seeking legal recognition of their lands and blocking destructive projects, including oil palm plantations, logging operations, and large-scale hydroelectric projects. Helping them is The Borneo Project, a Berkeley-based non-profit that works in partnership with indigenous communities and the small non-profits that support them.

The Borneo Project focuses its efforts in Sarawak, a Malaysian state where conflict between indigenous populations and developers is among the worst in Borneo. The group raises money for indigenous community-conceived campaigns and initiatives, while raising international awareness of their struggles against corruption, land-grabbing, and deforestation.

Many of the initiatives supported by the The Borneo Project aim to boost resilience of indigenous communities, including small-scale energy production, education, mapping native customary land, and providing legal aid to stop illegal encroachment by loggers and plantation developers. The group is currently raising money to print 3,000 indigenous language books for communities in Sarawak where reading materials are scarce, according to Brihannala Morgan, The Borneo Project’s Executive Director who spent time during her formative years living in indigenous communities in Borneo.

“We publish indigenous-language children’s books featuring traditional stories and art by local artists, giving the children in our schools (and other communities) access to locally appropriate reading material,” she told mongabay.com adding that The Borneo Project also runs three indigenous-language preschools, “teaching reading and writing to children who would otherwise not have access to education in their communities.”

“These preschools were the result direct requests from communities fighting logging and plantation expansion.”

Indigenous village in Sarawak. Image courtesy of The Borneo Project.

On an international level, The Borneo Project in involved with the Stop Timber Corruption in Sarawak campaign, which targets Sarawak’s chief minister Abdul Taib Mahmud for his role in allocating, developing, and profiting from logging and plantation concessions that destroy indigenous forests, and the SAVE Rivers Sarawak projects, which aims to stop a series of massive rainforest dams. Both issues have significant ramifications for Sarawak’s rainforests and forest-dependent people. They could have broader implications for Malaysian society as well — forestry and dams in Sarawak are sources of immense corruption.

Brihannala Morgan and The Borneo Project board member Judith Mayer discussed these issues and more during a July 2012 interview with mongabay.com.

AN INTERVIEW WITH THE BORNEO PROJECT

Mongabay.com: Who does The Borneo Project work with?

Indigenous community. Image courtesy of The Borneo Project. |

The Borneo Project: The Borneo Project works in partnership with indigenous communities and the small non-profits that support them, primarily in the Malaysian Province of Sarawak, on the island of Borneo. We do our best to provide support directly to the communities who are fighting logging, palm oil plantations, and the building of massive dams. The Borneo Project’s model is to take direction from the communities who are most impacted by the destruction of rainforests, and to provide those communities with the tools they request to help win their campaigns.

A good example of this model is our current partnership with the SAVE Rivers network in Sarawak. SAVE Rivers Sarawak – network of over 150 representatives from indigenous communities and local nongovernmental organizations – first gathered in October 2011 resist massive dam expansion planned for Sarawak’s rivers. They have held trainings and information sessions, held dramatic protests, and gotten extensive media coverage. This network, which includes groups the Borneo Project has partnered with over the years, asked us for help in funding their first gathering. We brought together a network in the United States that included International Rivers and the Rainforest Action Network (RAN) to pool funds. Now we are working with SAVE to raise awareness about dam expansion in Malaysia and helping them gather funds for their community-based workshops that they are using to organize resistance along the Baram River.

Mongabay.com: What can people — both inside and outside Malaysia — do to help your efforts?

The Borneo Project: We believe that the best way to support rainforest conservation and indigenous rights is to support communities who are at the front lines of these fights. We argue that the work that we need to be doing as allies – both in Malaysia and in the United States – is complex:

- We need to support communities that want to get legal access to their land. There are community-based organizations both in Malaysia and internationally – and solidarity based organizations like the Borneo Project – who are working directly with communities to promote land rights.

- We need to put pressure on governments to respect land rights and the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). We must support the groups that are taking indigenous rights to the worldwide decision makers at the United Nations and at global conferences.

- We need to put pressure on our non-profits to make sure that they are prioritizing the tough path that will lead to real conservation. We need to stop supporting the large non-profits that refuse to prioritize human rights over short-term publicity stunts.

- Finally, we need to educate our friends and colleagues who care about rainforest conservation, and help share the stories of forest conservation and human rights.

Mongabay.com: Why Borneo? What lead you to work on forest people’s issues in a place few have ever heard of?

The Borneo Project [Bria Morgan]: We fight for Borneo because of it’s incredible importance to the world’s climate, because the fight for indigenous communities in Borneo is microcosm of global right for indigenous rights, and because we have a deep, long-term, and personal connection to the island.

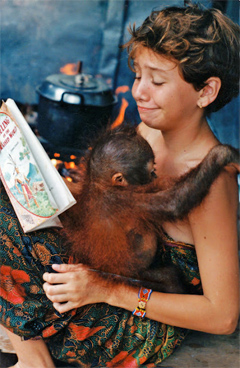

Bria Morgan in Borneo. |

On a personal level, Borneo is one of my homes. When I was nine years old, my mother and I moved to Borneo so she could do anthropological research. We lived in upriver villages in West Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, and Sarawak. When I was there as a child, the rivers were still clean, and the indigenous Kayan people we lived with still hunted and gathered in the forest for their food. I returned to Borneo in 2004 and found the island almost unrecognizable. Palm oil plantations had taken over all the land near the coast, and even upriver, logging and plantation expansion meant that the forests could no long support the community’s needs. Even the rivers were unfishable because of the pesticide run-off and erosion. I knew from then on that I wanted to do something to support these communities who I had grown up with, and to protect the incredible rainforests I had once called home.

On a more global level, Borneo faces rapid rainforest destruction, exploitation of fossil energy resources, and massive dam expansion. Incredible animals like the orangutan, the clouded leopard, forest elephants, the Borneo rhinoceros, sun bear, and many more are facing extinction as we get ever closer to destroying one of the last great rainforests of the world. The communities who call this island home are no longer able to support themselves using the forest, and are forced off the land that they have called home for countless generations as the government sells the land to companies who are only there for short-term gain.

The Borneo Project team. Judith Mayer is in the upper left in the back row, Bria is in the front on the lower right. |

Borneo is also critical to the global climate. The destruction and degradation of its tropical rainforests, wetlands, and peat-lands has resulted in massive greenhouse gas emissions. Indonesia – which controls 2/3 of the island of Borneo – is the world’s third largest emitter of greenhouse gases because of the emissions from burning forests, primarily for palm oil plantations. Borneo is also one of Asia’s premier sources of all major fossil fuels: petroleum, natural gas, and coal. This has both a global and local impact; exploitation of these energy commodities drive environmental destruction in many areas of Borneo’s forests and coastal waters.

Mongabay.com: The forest people of Sarawak have struggled for decades against loggers and now there are threats from industrial plantations and a series of dams. Can you provide some background on the people with whom you work and the threats they face?

The Borneo Project: The island of Borneo is home to 18 million people, almost 3 million of whom are members over 200 different indigenous communities, collectively known as Dayak. These communities share in the struggle to protect their forests and ancestral lands from destruction.

During the late 1980s, nonviolent protests against massive logging were led by ethnic Penan communities – the community then most fully dependent on intact rainforests. Dozens of other indigenous Dayak villages soon joined them – ethnic Kayan, Kenyah, Iban, Berawan, Lun Bawang, Kelabit, Bidayuh – blockading logging roads against massive logging to protect their forests and livelihoods. (At that time Sarawak and Kalimantan, across the border in Indonesia, were the world’s largest exporters of tropical timber products, derived entirely from forests that were also the ancestral lands of Borneo’s dozens of indigenous ethnic communities.)

Intact forest in Malaysian Borneo   Conversion of forest for oil palm plantations in Malaysian Borneo |

Sarawak’s many indigenous ethnic have distinct cultures, languages, and traditional livelihoods sustained by a resilient forest ecosystem. For hundreds of years, Dayak agricultural communities have supplemented small-scale rotational cultivation of rice and seasonal crops around longhouse centers with hunting, fishing, gathering forest products for use and for sale. They also nurtured forest gardens for their own needs and for cash, including smallholder production of trade commodities such as pepper and rubber.

“Customary” land rights and territories of Sarawak’s indigenous communities are protected under the state’s Land Law in Malaysia’s federal Constitution. The state’s Land Law clearly recognizes the “Native Customary Rights” of indigenous communities who have occupied or used the same agricultural and forest territory since before 1958. Yet the state also claims authority over forests and land use, and continues to grant leases and concessions to companies intending to log or develop corporate plantations on communities’ lands. Much of the indigenous land rights movement of the past 25 years strives to prove and enforce communities’ rights to control their own land in the face of an onslaught of state concessions and licensing to private companies and state-private joint ventures.

The Penan people of Sarawak have been in an even more tenuous position than other forest-dependent indigenous communities. Prior to the 1970s, the Penan were almost all nomadic hunter-gatherers in Sarawak’s inland rainforests. Most of the younger generations have now succumbed to state pressure to settle in permanent villages, as logging and plantations have destroyed the forests that supported their forebears. Because few Penan lived in settled agricultural villages prior to 1958, gaining state legal recognition of their forest land rights has been even more difficult than it has been for longer-settled Dayak communities, though a series of recent High Court decisions supports them. The Borneo Project works closely with Penan communities, particularly with our indigenous-language education program.

Corruption is central to the problems in Sarawak. Leading Sarawak politicians and their business cronies own the companies receiving state logging and plantation concessions and leases. Many have become millionaires, even billionaires, on profits from forest destruction – fortunes gained, in effect, from theft of indigenous communities’ resources. The profiteers include many family members and business associates of Sarawak’s Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud, who has remained in power for the last 33 years.

Mongabay.com: The forest people of Sarawak have won a series of legal victories only to see them ignored by local authorities. Is the best approach to keep fighting in court or are there other effective tactics for fighting threats facing them and their forests?

The Borneo Project: Sarawak’s people should use all nonviolent means at their disposal to protect their forests, and indigenous land rights. One aspect of this fight is the legal battle – there is enough of an independent judiciary in Malaysia to enable court victories in many cases. Successful lawsuits to protect communities’ land rights are also a crucial means to defending Sarawak’s indigenous communities, and Borneo’s rich forests. In addition to court cases, local people need to take direct action and seek international solidarity and support for their campaigns.

Stop Timber Corruption campaign. The Borneo Project has held protests at Taib-owned office buildings and properties in San Francisco and Seattle. Image courtesy of The Borneo Project. |

Yet a broader political struggle in Sarawak and across Malaysia must focus on the political will to defend and implement progressive court decisions on the ground. Some of the most effective individuals, communities, and organizations behind in the indigenous legal movement are also deeply engaged in electoral and parliamentary processes, and civil society resistance. For example, Dayak attorney Baru Bian, who has successfully represented dozens of indigenous community land rights cases against the state, was recently elected to the state legislature, and lawyer Harrison Ngau Laing, a founder of Borneo Project partner the Borneo Resources Institute (BRIMAS), served in the Malaysian parliament. He continues to be a key community land rights organizer. Indigenous communities are becoming much more sophisticated in electoral politics, though many activists are aware of the risk that this new activism could descend into a new focus for political patronage.

Opposition to “money politics” across Sarawak is apparent in dozens of new organizations in civil society and in community organizing, as well as in a wide variety of high-energy protest movements. Across Malaysia, the thousands who hit the street in recent “Bersih 3.0” demonstrations against corruption and the power of the wealthy in Malaysian electoral processes bear witness to a rising Malaysian consciousness about civil liberties, and civil society movements that are not divisive along sectarian and communal/ ethnic lines.

While the battle in the courts and on a national level is important, perhaps the most effective response is the communities’ efforts to promote their own visions of meaningful development – local conservation projects; village agroforestry initiatives; alternative energy efforts of all kinds; and a wide variety of locally based entrepreneurial projects based on sustainable and locally controlled use of local resources.

Indigenous village in Sarawak. Image courtesy of The Borneo Project.

Mongabay.com: Do the communities with whom you work want “development” (e.g. mobile phones, settled agriculture, even plantations) or something else? What’s the path for reaching this goal?

The Borneo Project: Why not ask them? The Borneo Project believes that the communities and organizations we work with in Sarawak should speak for themselves – our role is just to help their voices to reach a wider audience.

Image courtesy of The Borneo Project. |

All communities seek respect, dignity, sustainable livelihoods, and the right to determine their own futures. Currently, indigenous communities face the threat that their land will be taken and their forests destroyed without warning. This gives them the incentive to use as many of the forest resources as possible, as fast as possible. When communities are given legal rights to their land, they have the incentive to conserve it for future generations. They also have the local knowledge that is necessary to conserve the forest. In 2009 Dr. Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work showing that local communities with rights to their land can be highly successful at conserving it – even more successful than governments or outside non-profit organizations. While some communities may choose to develop the land they own, we know we will not get conservation results with the current system, and since communities need this land to survive, trying to restrict their access to this land will simply not work (and will also violates the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples).

We need to help communities get legal rights to their land, and to provide them with assistance and incentives to make use of that land sustainably. The Borneo Project’s first “technical assistance” initiatives actually involved providing communities involved in forest protests with cell phones to help them stay in touch with the “outside”, ensure access to medical assistance, and facilitate contact with distant communities. We have responded to communities’ requests for help in developing local electric power sources that they can control themselves – village micro-hydroelectric systems in the face of mega-dams. And we have helped communities develop sustainable integrated agroforestry systems based on experiments stemming from their own indigenous knowledge, rather than seeing wage labor on corporate plantations as the best way to bring in cash.

All of these local visions of appropriate development depend on retaining or gaining rights to control land. The legal and political struggle for land and forest rights has also called for education, skills, and technology. Helping communities to develop capabilities to map their own territories, and to envision their own futures on that land, has been a major focus of Borneo Project assistance since 1995. From basic surveying and sketch mapping, to sophisticated GIS systems, the Borneo Project has responded to local communities’ requests for technical assistance in gaining skills to define and delineate their own land, and envision futures for their own resources.

Mongabay.com: Chief Minister Taib is now in his late 70s. When he eventually steps down or leaves office do you expect to see much change in the way Sarawak is run?

The Borneo Project: Sarawakians are already fed up with the “money politics” of the past 35 years. The political opposition as well as a growing civil society movement both suggest reasonable courses of action and some likely political candidates to make the necessary changes.

Image courtesy of The Borneo Project. |

A big question will be whether opposition parties – several of which have been tightly associated with specific ethnic groups – will be able to band together in a viable reform coalition in time. The Peoples Justice Party (Parti Keadilan Rakyat), headed by indigenous legal rights lawyer Baru Bian, has put forward a reasonable reform program, and several other opposition groups associated with the Pakatan Rakyat are strategizing for a new coalition.

Opposition candidates committed to a fight against corruption, and for community resource control and conservation, made very substantial inroads in the last election. Opposition parties gained significant support even in areas where they did not actually win legislative seats. Recent revelations about the huge wealth that Sarawak’s current leaders have amassed at the expense of Sarawak’s people and resources have been shocking. (The Borneo Project has had a major role in those revelations, especially about the Taib family’s wealth hidden abroad, including in the USA.)

Political debate in Sarawak continues despite the ruling “Barisan Nasional” party’s attempts to suppress it, and focuses on how to bring about systemic change and reform in government operations. These debates almost take for granted that fundamental change must occur. The growing political reform movements throughout Malaysia, which have been increasingly visible in the past few months, provide a crucial context for opposition and indigenous community organizing in Sarawak.

Mongabay.com: Is there much interest in/concern about indigenous rights issues among the general public in Malaysia?

The Borneo Project: Yes, and increasing! Discontent with government “business as usual” highlights groups within Malaysia who have been most seriously affected by globalization’s down-side, especially for indigenous communities. Growing awareness of climate change, for example, puts indigenous struggles to protect forests and land rights into a new light. Once viewed as a battle of “anti-development” foreign environmentalists vs. modernization and development focused Malaysian capitalists, now urban Malaysians are increasingly standing with indigenous communities against the destruction of Malaysia’s resources in the name of short-term development.

Image courtesy of The Borneo Project. |

Over the past few years, Malaysia’s mainstream press has been inflamed by reports of Sarawak villages displaced by dams and plantations, sexual harassment and rape of Penan women and girls by loggers, and the twenty-year cover-up of crimes against their communities. Likewise, revelations of the mechanisms that Sarawak Chief Minister Taib’s family has used to accumulate and export its obscene wealth, through corruption and politically allocated contracts and monopolies, have also highlighted the legitimacy of marginalized indigenous groups’ struggles for legal and cultural rights.

On a national level, discontent grows against the corruption of Malaysia’s ruling political parties associated with UMNO (United Malay National Organization), as the recent spate of demonstrations by the Bersih 3.0 organizers has shown. Malaysians are aware that the brunt of economic hardship in the wake of Malaysia’s boom-and-bust economy has affected the most marginalized people the worst. Calls for indigenous rights gain new currency as models for forward thinking in Malaysian civil society. The politics of Malaysia’s leading opposition party firmly identifies rights for indigenous people across Malaysia.

Related articles