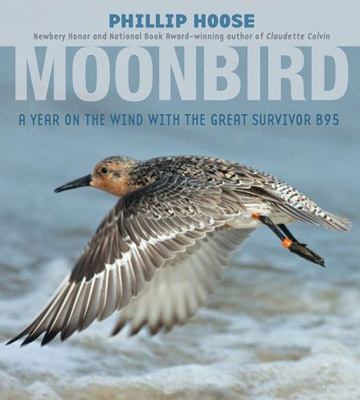

B95, the remarkable rufus red knot who has flown from the Earth to the moon in terms of distance. Photo by: Jan Van de Kam.

He is so long-lived that he has surpassed all expectations, touching hearts throughout the American continent, bringing together scientists and schools, inspiring a play and now even his own biography.

B95 is the name of a rufus red knot (Calidris canutus rufus), a migratory bird that in his annual journeys of 16,000 kilometers (9,940 miles) each way from the Canadian Arctic to Tierra del Fuego, in Argentina, has flown a distance bigger than the one between the Earth and Moon.

The story of B95 has inspired a book by American writer Phillip Hoose, which will be published next month. The bird has become a symbol of survival against all odds and of the plight of rufus red knots, whose populations have declined dramatically in recent years mainly due to overfishing in Delaware Bay, in the U.S., where the birds stop to refuel on their way back to the Arctic.

|

“We can’t believe this bird is still alive, because it has been through terrible situations. That’s why it is so special and everyone wants to see B95,” says biologist Patricia González, part of the team that ringed the bird in Argentina in 1995.

“Rufus red knots have faced so many declines that birds probably don´t live more than seven years,” says Gonzalez.

Allan Baker, an ornithologist with the Royal Ontario Museum who travels every year to Patagonia to work with González, has also been monitoring the bird since 1995.

“B95 is so popular because he is at least 18 years old, and maybe older because he may have been 3 or more years old when he was caught,” Baker told the BBC. “This is very old for a shorebird like a red knot, something like reaching a 100 if you were a human.”

Migratory route

Children in Patagonia who help with the release of birds captured for ringing.

“When we started ringing red knots in 1995 there was a system of colors agreed by all the countries in the Americas,” explains Gonzalez, who coordinates the Wetlands Program of the Inalafquen Foundation in the city of San Antonio Oeste.

The use of telescopes and digital cameras allows ornithologists to read the inscriptions on the flags of birds caught in previous years.

B95 has been seen on many occasions throughout his migratory route in the last few years and was last spotted in May in Delaware Bay.

Not all birds follow the same route. “We do not know B95´s exact journey except that he refuels in Delaware Bay in May before departing for the Arctic breeding ground in central Canada,” says Baker.

Red knots reach the Canadian Arctic in June to reproduce. A month later adults and juveniles start the journey back to Argentina, often stopping in the Mingan Archipelago in Quebec. They arrive in Tierra del Fuego, both in Argentina and Chile, around October and stay there until about February. Only recently scientists have discovered that some birds can fly non stop at least 8,000 kilometers (4,970 miles) to the U.S. from their wintering grounds in South America.

Delaware Bay, the great challenge

Red knots take-off in Delaware.

Rufus red knots face one of their toughest challenges in Delaware Bay, a crucial stop on their way to the Arctic.

“Delaware Bay supports the world’s largest population of horseshoe crabs and each May they come ashore and lay eggs on the beaches. There are so many that they start digging up eggs that were laid by other crabs so that eggs end up on the surface of the beach. This happens exactly at the time when red knots and other shorebirds are coming from their southern wintering area on their way to the Arctic,” says Larry Niles, a biologist with the Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey, who has been monitoring the birds for many years.

The eggs are almost all fat and when they are abundant the birds, which arrive in depleted conditions, can quickly gain up to double their body weight.

“Up until the early 90s commercial fishermen thought horseshoe crabs were of no value and there were millions of crabs coming ashore. But then they started getting good prices for welch and wanted bait to catch them,” Niles explains. “The harvest of crabs for bait went from a few hundred thousand each year to 2.5 million each year and because they don’t mature sexually until they are 9 or 10 years old they were quickly overharvested.”

By the early 2000s the population of crabs was less than a quarter of what it once was, according to Niles, and the reduction of eggs on the beaches led to a dramatic decline in shorebirds. “On Delaware Bay the numbers fell from nearly a 100,000 each year to about 15,000 last year.”

Fishermen are not the only ones catching horseshoe crabs. These animals are also being used as a source for lysate, a chemical used by the medical industry to test for contaminants in injectable drugs or implants.

“It is a huge, US$ 200 million industry and most of the world’s lysate is coming from Delaware bay crabs,” says Niles.

When crabs are caught for lysate, about a third of their blood is drained by puncturing their heart. The animals can recover if they are properly handled. Niles says 30 percent of the crabs harvested for bleeding die, which could represent a number as high as 600,000 crabs.

“What we are asking for is serious action, now that after many years there are some positive trends and we are getting an increase number of juveniles. We want more eggs on the bay,” he says.

Amongst the measures proposed by Niles are tighter controls of overfishing of crabs and better handling to reduce mortality and allow crabs to recover after bleeding.

“Most of the bleeding takes place outside Delaware Bay so the crabs have to be captured at sea in big nets and taken to a dock. There is one bleeder in Delaware Bay with a mortality rate of 5 percent. This shows they can recover if they are not overhandled and quickly put back into the sea.”

The Canadian government listed red knots as a threatened species this year, and conservationists are optimistic that the US will follow suit.

This would mean in practical terms that any project that requires alteration to red knot habitats will now have to consider its impacts on the birds.

“B95 INSPIRES ME”

Patricia Gonzalez with a rufus red knot. Photo by: Guy Morrison.

B95 was last seen on the 29th of May in Delaware Bay by Patricia Gonzalez.

“I couldn’t believe it when I used my telescope and confirmed it was B95. He is so old that I was not expecting to see him again. My hands were trembling when I tried to use my camera to take a picture through the telescope,” she said.

Gonzalez travels to Delaware every year to help monitor the birds. This year she carried letters from children in Argentina to a school in New Jersey.

“Kids started communicating because of the birds via Skype.”

The birds have brought together scientists, volunteers and schools, and none has done so more than B95.

Phillip Hoose hopes his book will bring the story of this great bird to a wider public.

“I draw inspiration from B95. If he can thread the needle year after year, flying through ever more turbulent skies to reach ever more scarce resources, then we can double our efforts to save shorebirds,” Hoose told the BBC.

“B95 represents, hope, grit, adaptability, strength, determination. We need to respect and learn more to help the little shorebirds with whom we share the worlds shores. They are among the most marvelous athletes in existence.”

Most recent photo of B95. Photo by: Patricia M. Gonzalez.

Related articles

Why bird droppings matter to manta rays: discovering unknown ecological connections

(06/04/2012) Ecologists have long argued that everything in the nature is connected, but teasing out these intricate connections is not so easy. In fact, it took research on a remote, unoccupied island for scientists to discover that manta ray abundance was linked to seabirds and thereby native trees.

Herp paradise preserved in Guatemala

(05/29/2012) Fifteen conservation groups have banded together to save around 2,400 hectares (6,000 acres) of primary rainforest in Guatemala, home to a dozen imperiled amphibians as well as the recently discovered Merendon palm pit viper (Bothriechis thalassinus). The new park, dubbed the Sierra Caral Amphibian Reserve, lies in the Guatemalan mountains on the border with Honduras in a region that has been called the most important conservation area in Guatemala.

Featured video: baby hornbills grow up in a jar

(05/29/2012) A researcher in Malaysia has captured footage of Oriental pied hornbills (Anthracoceros albirostris) raising chicks in an earthen jar in the Kenyir rainforest of Malaysia. The first video shows the father Oriental pied hornbill feeding the chicks, while the second shows a chick leaving its nest.

Picture: Happy migratory bird day

(05/13/2012) May 12-13 is World Migratory Bird Day for 2012.

Scientists count penguins by satellite, find twice as many as expected (photos)

(04/14/2012) The population of emperor penguins in Antarctica is nearly twice as high as previously estimated according to a new satellite-based assessment.

Baby boom: 18 of the world’s rarest duck born

(04/06/2012) The global population of one of the world’s rarest birds just increased 43 percent. The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust is reporting that 18 Madagascar pochards — the world’s rarest duck — hatched and are now being reared at a facility in Madagascar. The breeding program is a joint effort between Durrell, the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT), the Peregrine Fund, Asity Madagascar and the Government of Madagascar.

Turkey’s rich biodiversity at risk

(03/28/2012) Turkey: the splendor of the Hagia Sophia, the ruins of Ephesus, and the bizarre caves of the Cappadocia. For foreign travelers, Turkey is a nation of cultural, religious, and historic wonders: a place where cultures have met, clashed, and co-created. However, Turkey has another wealth that is far less known: biodiversity. Of the globe’s 34 biodiversity hotspots, Turkey is almost entirely covered by three: the Caucasus, the Irano-Anatolian, and the Mediterranean. Despite its wild wealth, conservation is not a priority in Turkey and recent papers in Science and Biological Conservation warn that the current development plans in the country, which rarely take the environment into account, are imperiling its species and ecosystems.

Over 5,000 vital biodiversity sites remain unprotected

(03/22/2012) A recent study has found that half of the world’s Important Bird Areas (IBAs) and Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE) sites remain unprotected, leaving many endangered species, some on the verge of extinction, gravely vulnerable to habitat loss. Published in the open access journal PLoS ONE, the study urges governments to focus on expanding protected areas to cover the species that need it most.

Birders beware: climate change could push 600 tropical birds into extinction

(02/21/2012) There may be less birds for birders to see in the world as the planet warms. Climate change, in combination with deforestation, could send between 100 and 2,500 tropical birds to extinction before the end of century, according to new research published in Biological Conservation. The wide range depends on the extent of climate and how much habitat is lost, but researchers say the most likely range of extinctions is between 600 and 900 species, meaning about 10-14 percent of tropical birds, excluding migratory species.