150 new dams may destroy connectivity of the Amazon River to the Andes and drive deforestation.

Construction of a canal for the Belo Monte Dam project, near Altamira taken by Daniel Beltrá for Greenpeace. Once completed, the Belo Monte Dam will be the third largest in the world. It will submerge up to 400,000 hectares and displace 20,000 people. Image © Daniel Beltrá / Greenpeace.

More than 150 new dams planned across the Amazon basin could significantly disrupt the ecological connectivity of the Amazon River to the Andes with substantial impacts for fish populations, nutrient cycling, and the health of Earth’s largest rainforest, warns a comprehensive study published in the journal PLoS ONE.

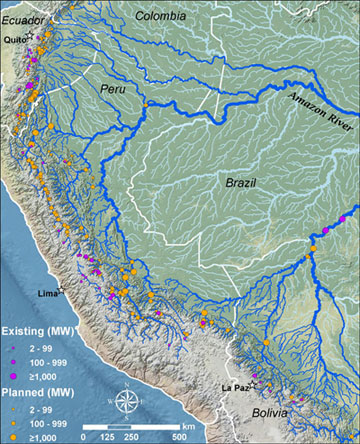

Scouring public data and submitting information requests to governments, researchers Matt Finer of Save America’s Forests and Clinton Jenkins of North Carolina State University documented plans for new dams in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. They found that 40 percent of the projects are already in advanced planning stages and more than half would be large dams over 100 megawatts. 60 percent of the dams “would cause the first major break in connectivity between protected Andean headwaters and the lowland Amazon”, while more than 80 percent “would drive deforestation due to new roads, transmission lines, or inundation.”

“These results are quite troubling given the critical link between the Andes Mountains and the Amazonian floodplain,” said lead author Finer in a statement. “There appears to be no strategic planning regarding possible consequences to the disruption of an ecological connection that has existed for millions of years.”

Lake Balbina, a man-made reservoir created to supply hydroelectric power to the city of Manaus in Brazil. (Photo courtesy of Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC)

Finer and Jenkins note that the Andes are a critical source of sediments, nutrients, and organic matter for the Amazon river, feeding the floodplain that supports the rich Amazon rainforest. The Amazon and it tributaries are critical highways for migratory fish that move to headwaters areas to spawn.

“Many economically and ecologically important Amazonian fish species spawn only in Andean-fed rivers, including a number that migrate from the lowlands to the foothills,” the authors write. “The Andean Amazon is also home to some of the most species rich forests and rivers on Earth. The region is documented to contain extraordinary richness for the most well studied taxa… and high levels of endemism for the understudied fishes. Therefore, any dam-driven forest loss or river impacts are of critical concern.”

Finer and Jenkins conducted a meta-analysis of river connectivity and infrastructure to produce an “ecological impact score” for all 151 dams. 47 percent of the dams were classified as “high impact” while only 19 percent were rated “low impact”. Eleven of the dams would directly affect a conservation area.

Planned dams in the Amazon Basin, according to the new paper. Click image to expand or here for a very large version of the map. |

The hydroelectric projects would also have social impacts. Forty dams would be constructed “immediately upstream or downstream” on an indigenous territory.

Worryingly the authors conclude that there is seemingly no basin-wide policy assessment of the potential social and ecological impacts of the dam-building spree.

“We conclude that there is an urgent need for strategic basin scale evaluation of new dams and a plan to maintain Andes-Amazon connectivity,” said study co-author Jenkins in a statement. “We also call for a reconsideration of the notion that hydropower is a widespread low impact energy source in the Neotropics.”

Finer and Jenkins warn that the perception dams in tropical forest areas are a clean energy source could lead to perverse subsidies for the projects via the carbon market.

“Institutions and instruments that support Neotropical dams, such as international financial institutions and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), should consider the wide array of factors examined here during project evaluations,” they write. “Otherwise, tropical rivers and forests may increasingly be at risk from otherwise well-intentioned strategies to mitigate climate change.”

Phil Fearnside, an esteemed researcher at the National institute for Research in Amazonia (INPA) who wasn’t involved with the paper but has conducted extensive analysis of greenhouse gas emissions from Amazon dams, agrees.

“The other reason giving these dams CDM credit is bad for climate is that virtually none of them are additional,” Fearnside told mongabay.com. “In other words, the dams are being built anyway, and giving them credit both wastes the resources for fighting global warming and allows the countries that purchase the credit to emit more carbon.”

The bigger picture

Study author Finer says that governments need to take a hard look at current plans for dam development, which could affect the long-term productivity of the very ecosystems that sustain Amazon rivers.

“As governments of the Andean Amazon region are prioritizing hydropower as the centerpiece of long-term energy plans, strategic planning is needed to mimimize impacts of a planned wave of new dams in the most biologically diverse zone on Earth,” he told mongabay.com.

“Up to now all six major connections between the Andes and Amazon have been largely free-flowing. With the construction of the two mega dams on the Madeira we’ll soon be down to five. We documented many plans for three more major rivers (Ucayali, Maranon, and Napo), so pretty soon we could be down to two. What will be the implications of that?”

“These dams could have extremely far-reaching impacts on the Amazon, stretching from the high Andes all the way to lowland Brazil,” added Jenkins. “The full ecological impacts may be unpredictable and potentially irreversible.”

Finer M and Jenkins CN (2012) Proliferation of Hydroelectric Dams in the Andean Amazon and Implications for Andes-Amazon Connectivity. PLoS ONE 7(4): e35126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035126