Ocean acidification growing at a rate faster than anytime in 300 million years.

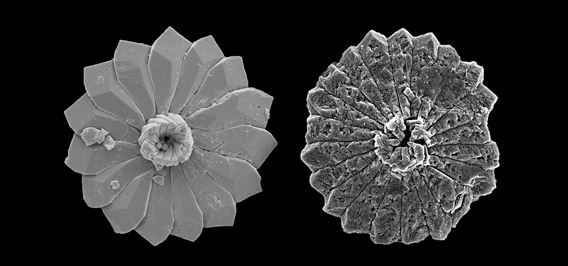

To the left a discoaster of marine plankton before an ocean acidification event 56 million years ago, and to the right its counterpart corroded by ocean acidification event. Image taken with a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Human emissions of carbon dioxide may be acidifying the oceans at a rate not seen in 300 million years, according to new research published in Science. The ground-breaking study, which measures for the first time the rate of current acidification compared with other occurrences going back 300 million years, warns that carbon emissions, unchecked, will likely lead to a mass extinction in the world’s oceans. Acidification particularly threatens species dependent on calcium carbonate (a chemical compound that drops as the ocean acidifies) such as coral reefs, marine mollusks, and even some plankton. As these species vanish, thousands of others that depend on them are likely to follow.

“We know that life during past ocean acidification events was not wiped out—new species evolved to replace those that died off. But if industrial carbon emissions continue at the current pace, we may lose organisms we care about—coral reefs, oysters, salmon,” lead author Bärbel Hönisch, a paleoceanographer at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said in a press release.

Nearly a third of the world’s carbon emissions ends up in the oceans. As the rate of CO2 emissions in the oceans speeds up—passing normal ranges in the global carbon cycle—the ocean’s pH levels fall, equating to a rise in acidity. During the last hundred years, pH rates have fallen 0.1 units. While the number sounds small, it’s an incredibly rapid dip in just a century.

The worst ocean acidification period in the last 300 million years was during a climate upheaval event 56 million years ago, known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Over a period of about 20,000 years, the oceans’ pH levels fell approximately 0.45 units while temperatures rose about 6 degrees Celsius (11 degrees Fahrenheit). The result: mass extinction.

“Due to volcanic emissions and the destabilization of frozen methane hydrates on the ocean floor, large amounts of carbon were freed into the atmosphere, comparable to levels humans may achieve in emitting in the future. Large extinctions took place during that period, especially of benthic fauna,” explains Carles Pelejero, researcher at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) Institute of Marine Sciences and paper co-author.

Although current declines in pH are not yet so severe, they are falling at least 10 times faster than during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Even more alarming, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that current pH rates could plunge another 0.3 units by 2100.

“[This] augurs more catastrophic consequences caused by current anthropogenic change,” Pelejero notes.

Ocean acidification has occurred two other times: around 201 million years ago and then again about 50 million years later. However a dearth of data has made these events more difficult to analyze, though researchers know that both times coincided with mass extinction.

Scientists say there is currently only one way to counteract ocean acidification and prevent mass extinction.

“There is no doubt that we must tackle the problem at its roots as soon as possible, adopting measures to immediately reduce our CO2 emissions into the atmosphere,” says another co-author Patrizia Ziveri, a researcher with the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA).

CITATION: Bärbel Hönisch,

Andy Ridgwell,

Daniela N. Schmidt,

Ellen Thomas,

Samantha J. Gibbs,

Appy Sluijs,

Richard Zeebe,

Lee Kump,

Rowan C. Martindale,

Sarah E. Greene,

Wolfgang Kiessling,

Justin Ries,

James C. Zachos,

Dana L. Royer,

Stephen Barker,

Thomas M. Marchitto Jr.,

Ryan Moyer,

Carles Pelejero,

Patrizia Ziveri, Gavin L. Foster, Branwen Williams. The Geological Record of Ocean Acidification. Science. Vol. 335 no. 6072 pp. 1058-1063. DOI: 10.1126/science.1208277.

Related articles

Acid oceans: in some regions acidification a ‘hundred times greater’ than natural variation

(01/24/2012) Emissions of carbon over the last two centuries have raised the acidity of the oceans to the highest levels in 21,000 years and likely beyond, according to a new study in Nature Climate Change. The change threatens a number of marine species, including coral reefs and molluscs.

Ocean prognosis: mass extinction

(06/20/2011) Multiple and converging human impacts on the world’s oceans are putting marine species at risk of a mass extinction not seen for millions of years, according to a panel of oceanic experts. The bleak assessment finds that the world’s oceans are in a significantly worse state than has been widely recognized, although past reports of this nature have hardly been uplifting. The panel, organized by the International Program on the State of the Ocean (IPSO), found that overfishing, pollution, and climate change are synergistically pummeling oceanic ecosystems in ways not seen during human history. Still, the scientists believe that there is time to turn things around if society recognizes the need to change.

Ocean acidification dissolves algae, deafens fish

(06/02/2011) As if being a major contributor to global warming wasn’t enough, the increasing amount of carbon dioxide produced through human activity is also acidifying our oceans – and doing so more rapidly than at any other time in more than half a million years. New projections show that at current rates of acidification, clownfish and many species of algae may be unable to survive by 2100.