The giant river otter. Photo by: Frank Hajek.

Behavior and conservation of the Amazon’s giant river otter.

Charismatic, vocal, unpredictable, domestic, and playful are all adjectives that aptly describe the giant river otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), one of the Amazon’s most spectacular big mammals. As its name suggest, this otter is the longest member of the weasel family: from tip of the nose to tail’s end the otter can measure 6 feet (1.8 meters) long. Living in closely-knit family groups, sporting a complex range of behavior, and displaying almost human-like capricious moods, the giant river otter has captured a number of researchers and conservationists’ hearts, including Dutch conservationist Jessica Groenendijk.

“Otters have always had tremendous appeal for me, ever since reading Gavin Maxwell’s Ring of Bright Water, and the idea of a ‘giant’ otter was entrancing,” Groenendijk told mongabay.com in an interview. After obtaining a Masters degree in Aquatic Resource Management from King’s College, London, Groenendijk was recruited to become Project Leader of the Frankfurt Zoological Society Giant Otter Conservation Program. “I was very fortunate. Our first encounter with a giant otter family was a deeply impressive experience and I was hooked. This was the start of what I believe, and hope, will be a life-long commitment to the giant otter.”

Jessica Groenendijk walking up a stream in the hope of filming a transient giant otter. Photo courtesy of Jessica Groenendijk. |

Researchers are just beginning to untangle some of the complex familial relations in giant river otter communities, who live together in related groups of around a dozen individuals. These family groups are overseen by one breeding couple, but do pretty much everything together.

“Groups are highly cohesive: they hunt, mark their territories, sunbathe, and sleep together, with bonds constantly reinforced by mutual grooming and play,” explains Groenendijk, adding that “a giant otter family has much in common with a human family, which is why observing them over many years has something of the soap opera about it. There’s drama, bickering, unity in the face of a caiman threat, babysitting and shared feeding of the cubs, and, finally, offspring leaving home. If fate is kind, a breeding pair may stay together for up to 10 years.”

Researchers have found that these family groups practice alloparenting, which means non-parents also participate in raising cubs, not unlike many human communities. In addition, a recent observation found young otters purposefully feeding an aged matriarch, who likely had difficulty hunting for herself. Even with such insights, Groenendijk says there is much scientists don’t yet know about the private lives of giant river otters.

“We know almost nothing of the dynamics of transient animals once they have left their families. Where do they go, how far do they travel, what threats do they face, how are new groups formed? Unfortunately, telemetry in the rainforest is hampered by local conditions: we need to devise innovative ways of radio tracking giant otters.”

In addition, researchers are trying to figure out the natural causes behind giant river otter mortality: for example they believe infant mortality is high, but have had difficulty collecting data on it in the absence of bodies. Mating behavior and predator/prey relationships also remain largely obscure.

But even as scientists are making strides in uncovering giant river otter behavior, there is a sense that they are racing against time as the Amazon ecosystem faces changes from deforestation, mining, roads, and climate change. Although the giant river otter is found in ten Amazonian nations, it remains endangered. Almost driven to extinction by the pelt trade, which was banned in 1975, the giant river otter today faces a number of new and rising direct threats tyhat have held back a full recovery. A surge in gold mining, habitat destruction, pollution, conflict between humans and otters over fish resources, and even poorly-managed tourism have all injured giant river otter populations.

View from the observation tower in Cocha Otorongo, Manu National Park. Photo by: Frank Hajek. |

“Artisanal gold mining is out of control in the Department of Madre de Dios, with all the devastation this implies. The increase in gold-mining activity along the Madre de Dios, Malinowski, and Inambari Rivers has resulted in near local extinction of the species with giant otters only surviving in tributaries and lakes where there is no mining activity,” Groenendijk says, adding that this raises the question of mercury pollution from gold mining possibly “bio-accumulating in giant otters and affecting their reproductive health and survival.”

Conflict between fishermen and giant river otters is another problem unique to the species. “Giant otters are blamed, with little justification, for declining fish stocks: they are perceived to be competing with fishermen for the same species,” says Groenendijk who adds that most likely overfishing and other environmental problems are behind the decline in fish stocks in some regions, not a few otter families.

Even tourism projects can injure giant river otters by causing stress and destroying habitats, though Groenendijk says there are a number of simple measures to ensure tourists and giant river otters can co-exist, and even benefit, from controlled visits to otter lakes.

As with most endangered species, conserving the giant river otter means more than simply making sure its forests aren’t cut down explains Groenendijk: it means dealing with the artisanal, and often illegal, gold mining trade; education and awareness programs for people living near otter families; more research on the ecology of otters and a greater understanding of their habitat and prey requirements; and more and better-managed protected areas. But, in the end, the goal of achieving a thriving giant river otter population will require safeguarding the Amazon basin from a multitude of threats, a task that scientists say would benefit hundreds of thousands of species, both known and unknown, as well as all of human society.

With their playful nature, their dramatic lifestyles, and their large personalities, giant river otters could be great ambassadors for the conservation of the Amazon, both in Amazonian states and abroad.

INTERVIEW WITH JESSICA GROENENDIJK

A giant otter grooming (or praying!). Photo by: Frank Hajek.

Mongabay: What is your background?

Jessica Groenendijk: I’m a Dutch biologist turned conservationist with a Biology degree from Imperial College and an Aquatic Resource Management Masters from King’s College, London. Starting as a volunteer, I worked for 4 years at the Netherlands Committee for IUCN as Coordinator of the European Working Group on Amazonia (a network of 300 individuals, NGOs, and governmental institutions involved in conservation and sustainable development in the nine Amazon countries). This led to my becoming Project Leader of the Frankfurt Zoological Society Giant Otter Conservation Project in 1999, implementing applied research and conservation activities for this species in protected areas of the Madre de Dios region of Peru, including the development of site plans for tourism management in giant otter habitats, and education materials that have been replicated in several South American countries. I also monitored demography of key populations of the species and, in my position as Giant Otter Species Coordinator for the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group, catalyzed the development of monitoring guidelines across the species distribution range, working together with giant otter specialists from 8 countries. By 2005, kids Saba and Luca had appeared on the scene, and after completing our popular/scientific book Giants of the Madre de Dios we moved to North Luangwa National Park, Zambia, where I was Technical Advisor to the North Luangwa Conservation Program of the Frankfurt Zoological Society, responsible for the monitoring of the reintroduced black rhino population, and managing the NLCP Conservation Education Program. In 2008, while in the UK, I began the analysis and write-up of 14 years of giant otter data, with the support of Oxford University’s WildCRU. This was temporarily interrupted when we moved to Cusco, Peru at the end 2010. Here since July 2011, I have been working for San Diego Zoo Global as Education and Outreach Coordinator of the beautiful Cocha Cashu Biological Station in Manu National Park. I am responsible for engaging with people from all levels of society—from local school children, to Peruvian and international students and researchers, to Protected Area staff and government officials—towards the research and conservation of tropical biodiversity.

Mongabay: What first attracted you to study giant river otters?

Jessica Groenendijk: While at university, I co-led two expeditions to Manu National Park and the Las Piedras River. We caught brief, tantalizing glimpses of giant otters during both journeys. Otters have always had tremendous appeal for me, ever since reading Gavin Maxwell’s Ring of Bright Water, and the idea of a ‘giant’ otter was entrancing. The fact that the species was endangered made our sightings all the more special, and I reported back to my then employers at the Netherlands Committee for IUCN with great enthusiasm and a sense of urgency. When the International Fund for Animal Welfare was looking for someone to carry out a desk study into the conservation status of the giant otter in South America, my boss thought of me. One thing led to another, and within two years of completing the study, I found myself in Peru, newly married, and joint Coordinator of Frankfurt Zoological Society’s Giant Otter Research and Conservation Project. I was very fortunate. Our first encounter with a giant otter family was a deeply impressive experience and I was hooked. This was the start of what I believe, and hope, will be a life-long commitment to the giant otter.

GIANT RIVER OTTER BEHAVIOR

A giant otter cub begging a morsel from older sibling. Photo by: Frank Hajek.

Mongabay: Giant river otters are highly social animals. How is a family group usually structured?

Jessica Groenendijk: A family group consists of a single, monogamous breeding pair plus their offspring of several years, from tiny cubs to adults. Average group size in Manu is about 6, with the largest consisting of 14 members, in Cocha Salvador. Groups are highly cohesive: they hunt, mark their territories, sunbathe, and sleep together, with bonds constantly reinforced by mutual grooming and play. A giant otter family has much in common with a human family, which is why observing them over many years has something of the soap opera about it. There’s drama, bickering, unity in the face of a caiman threat, babysitting and shared feeding of the cubs, and, finally, offspring leaving home. If fate is kind, a breeding pair may stay together for up to 10 years.

Mongabay: How do giant river otters communicate?

Jessica Groenendijk: Loudly and frequently! Giant otters are extremely vocal and use a large number of different sounds to communicate under different circumstances. Anything unexpected or strange will be met by a series of explosive exhalations, while the otters periscope to get a better look. A mother will initiate a new activity with a lilting hum, meaning “Let’s go.” Cubs beg for fish from their older siblings with ear-splitting shrieks that can be heard hundreds of meters away. And when one wails a warning, all group members rush together and ululate at top volume, a powerful vocalization that gives me goose bumps.

Mongabay: What is ‘alloparenting’? How does this play into the giant river otters’ success?

Giant otter consuming a fish. Photo by: Frank Hajek. |

Jessica Groenendijk: Alloparenting is where individuals other than the parents assist with the rearing of young. In giant otters, older siblings help feed cubs and juveniles by giving them fish (sometimes reluctantly!), by rushing to their defense in the face of danger, by helping to carry them from one den to another, and, occasionally, by babysitting them in the den while the mother hunts with the rest of the group. The larger a giant otter group, the more it is a force to be reckoned with. Group size plays a role in hunting success, defense against predators, and the ability to hold on to a territory. Alloparenting helps to increase the survival rate of cubs and juveniles, and hence increases group size.

Mongabay: A 2010 study recorded young giant river otters giving food to an elderly matriarch. Does this study’s findings fit with your own observations of giant river otters?

Jessica Groenendijk: Actually, I believe this is the first time such behavior has been recorded, by Lisa Davenport. I’m familiar with the giant otter group involved. The matriarch was at least 13 years old when she finally disappeared, to be replaced by her daughter. During her last year, she was much less mobile and Lisa witnessed the neat reversal of roles you mention. The male of the group was a relative newcomer and the old female’s knowledge of the territory may well have been her only, but significant, contribution to the group’s well-being. However anthropomorphic it may seem, I’m sure that strong familial bonds also played a role.

Mongabay: What are some research questions regarding behavior that you would really like to see addressed?

Black caiman are known to prey on giant river otters. Photo by: Frank Hajek. |

Jessica Groenendijk: Where do I start?! Over the years of giant otter observation, many intriguing questions have surfaced. In fact, the more we learn, the more we wonder! Unfortunately, the most interesting may the most difficult to address. For example, we know very little about natural giant otter mortality factors. Incredibly, during years of research in Madre de Dios, we found only one dead giant otter, a decomposing newborn cub at the entrance of a den. We do know that cub mortality is high, but can only guess at the causes. We have our suspects: attacks by caiman, high parasite load, and abandonment by stressed or inexperienced mothers, amongst others. Incidents in Brazil suggest that conflicts between otter groups or between transient individuals (and groups) may be an important mortality factor.

We know a little now about the ecology and behavior of giant otter groups. However, we know almost nothing of the dynamics of transient animals once they have left their families. Where do they go, how far do they travel, what threats do they face, how are new groups formed? Unfortunately, telemetry in the rainforest is hampered by local conditions: we need to devise innovative ways of radio tracking giant otters.

Another big question concerns genetics. For example, how related are the individuals in a giant otter group? Are the breeding pair really monogamous, or does a transient male occasionally manage to sneak a mating when the resident male isn’t paying attention? Some studies have been carried out using fecal samples, but since group members enthusiastically mix their scat on latrines, it has proved almost impossible to identify individuals. Giant otter researchers are beginning to explore ways around this problem and it will be extremely interesting to see what they find.

Lastly (although if you asked another giant otter specialist the same question, you would get a different list of priorities), it would be useful to learn more about predator/prey relationships. We know that giant otters each consume up to 4kg of fish daily, and we know the species they prefer. But what impact do they have on fish populations, or vice versa? And with artisanal gold mining rife in Madre de Dios, is mercury bio-accumulating in giant otters and affecting their reproductive health and survival?

ENDANGERED: MINING, CONFLICT, AND TOURISM

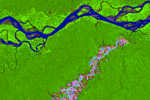

Aerial picture of gold mining damage in Peru’s Amazon rainforest. The gold mining boom is a perilous threat to the giant river otter. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Mongabay: Historically what was the big threat to this river mammal?

Jessica Groenendijk: Hunting for the pelt trade throughout its range was the single, greatest threat to the giant otter and is directly responsible for its current endangered status (although more recent threat factors are contributing to the maintenance of this status). Between 1946 and 1973, 23,980 giant otter pelts were officially exported from Peru alone, excluding those skins which were exported via Leticia, Colombia. The export of pelts from Peru was banned in 1970 and professional hunting of wildlife in the Peruvian Amazon was prohibited in 1973. But it was the inclusion of the giant otter in Appendix I of CITES in 1973, and the coming into force of international trade restrictions on giant otter skins in 1975 that finally ended the economic benefits of giant otter hunting.

Mongabay: What are the major threats to giant river otters in Peru today?

Jessica Groenendijk: Habitat loss, human/giant otter conflict (over fish resources), and contamination of aquatic ecosystems due to gold mining are probably the most important threats right now. Giant otters are blamed, with little justification, for declining fish stocks: they are perceived to be competing with fishermen for the same species. Artisanal gold mining is out of control in the Department of Madre de Dios, with all the devastation this implies. The increase in gold-mining activity along the Madre de Dios, Malinowski, and Inambari Rivers has resulted in near local extinction of the species with giant otters only surviving in tributaries and lakes where there is no mining activity.

Mongabay: Do they face different threats elsewhere?

Miner pours mercury used in gold mining. Mercury is a toxic substance both to humans and otters. Photo by: Frank Hajek. |

Jessica Groenendijk: No, threats are similar (to a lesser or greater degree) in other countries of the giant otter’s distributional range. It is interesting that human/giant otter conflict is emerging as an increasingly common problem. Although it is true that in some few areas giant otter populations are slowly recovering, the issue is much more likely a product of overfishing by humans themselves. Infrastructure and hydroelectric development is perhaps a greater threat in Brazil. And poorly managed tourism—the subject of intensive effort in Peru by the Frankfurt Zoological Society and their counterparts in Peru’s Protected Area Service (SERNANP)—has been mentioned as an emerging problem in Brazil and Bolivia.

Mongabay: Illegal gold mining has become a major problem on the Madre de Dios. How does this impact giant river otter populations?

Jessica Groenendijk: I recently read in a paper by Swenson et al that the Department of Madre de Dios is Peru’s third largest producer of gold and generates 70% of Peru’s artisanal gold production. Over the last decade, the price of gold has increased 360% with a constant rate of increase of about 18% per year. Peruvian mercury imports have risen 42% between 2006 and 2009 to 130 t/yr, almost all of which is used directly in artisanal gold mining. Forest conversion to mining increased six-fold from 2003-2006 (292ha/yr) to 2006-2009 (1915ha/yr). Gutleb, Schenck and Staib found in 1997 that mercury concentrations in the majority of fish in the area of Manu National Park were higher than what is considered tolerable in the Eurasian otter. But the expected high concentrations of methylmercury in giant otter tissues have not been corroborated due to the difficulty of finding dead giant otters. In any case, habitat destruction is the most immediate and severe impact of gold mining: surveys by the Frankfurt Zoological Society in 2008 and 2010 in areas with gold-mining failed to find any sign of giant otter presence.

Mongabay: What are the best estimates of total population? Why are such estimates so hard to get?

Jessica Groenendijk: I’m reluctant to put forward a best estimate for total population size since we really don’t know. Someone once threw the number 5,000 into the air, and this has been cited repeatedly, but I believe it was a rather wild guess. As a result of surveys, we have good estimates for some river systems but not for any country as a whole. Giant otters occur in a wide variety of often remote and inaccessible habitats in the lowland rainforest and wetlands of at least 10 South American countries with complex political realities; these are difficult conditions for obtaining reliable estimates.

TARGETED CONSERVATION AND EDUCATION

Tourists view giant river otters from a fixed observation platform on Cocha Salvador. Photo by: Frank Hajek.

Mongabay: Is tourism a threat to giant river otters?

Jessica Groenendijk: Tourism and giant otters can have a troubled relationship, depending on how tourism is managed (or not). The giant otter is one of very few large, endangered mammals that are relatively easily observed in the rainforest. It inhabits rivers and lakes, the ‘highways’ of this complex ecosystem, in stable territories that often become accessible, reliable destinations for tourist excursions. Giant otters are highly social, living in vocal family groups that hunt by day. They are attractive and active; in short, this charismatic animal easily becomes a focal point for tourism. But to place too much emphasis on a single species as a tourist attraction is risky; it can result in disappointed visitors if their expectations are not met, in guides who feel pressured to come up with the goods and so may go to considerable lengths to satisfy their customers, and in otters that learn, through bitter experience, to avoid human presence.

Very often, it is a question of misunderstanding. Giant otters react to people as they do to caimans, perceiving us as a potential threat. Their characteristic behavior is one of warning. By approaching rapidly and periscoping around us while repeatedly uttering loud snorts, they are informing us that we are invading their space and that they are alarmed. But we interpret this attitude as one of tameness. If we then fail to acknowledge their warning and row even closer to take the perfect photograph, the otters eventually feel forced to move on. In future encounters, they will learn to steer clear of this ‘super predator,’ and tourists will no longer have satisfactory viewing experiences. This is just one example of how poorly managed tourism can reduce habitat quality for giant otters. However, not only do we sometimes interfere with their activities on the water, we also build infrastructure and clear paths directly along shorelines, thereby preventing otters from constructing their dens or latrines.

Environmental education using the giant otter as an ambassador species. Photo by: Frank Hajek. |

A far more serious impact of tourism is lowered reproductive success. The height of the tourism season in Peru is preceded by a few months by a peak in giant otter births; in August/September, most otter families are rearing up to four vulnerable cubs in their den. Giant otters, especially the parents, are much more nervous at this time of year. In zoos, it was discovered to everybody’s surprise that females may fail to nurse their cubs as a result of stress induced by visitors. They are surrounded by people all year round, yet when they have cubs, captive otters become highly sensitive to outside influences.

Experience in Peru has shown that tourism and giant otters can co-exist harmoniously, even thrive together, if the former is managed in such a way as to respect the needs of the latter. Giant otters prefer large oxbow lakes with plenty of fish and high, path-free shorelines for building dens and latrines. If tourism could take these habitat requirements into account, then not only would giant otters benefit by being able to lead uninterrupted lives, their cubs safe, but our chances of observing these wonderful animals for long periods in their natural habitat would be greatly increased since they would feel at ease in our presence. Such an extraordinary experience would bring us back to the rainforest time and again.

So what can we do as responsible guides, lodge owners and tourists? Guides should inform themselves as well as possible about giant otter biology and behaviour. A minimum observation distance between ourselves and the otters should be maintained, and binoculars should be used at all times. Lodges should not be constructed directly on lake shores and paths should be cleared away from the shoreline, at least 100 meters inland. Boats should be rowed slowly and quietly along a fixed route, and a zone in each lake should be set aside as a refuge for giant otters and other animals. In addition to finding alternatives to lake excursions, fixed observation points (hides, towers, platforms) should replace boats as much as possible; these are static, predictable sources of disturbance that do not interfere with otter activities and which the animals can avoid if they wish. But experience in south-eastern Peru has shown that they don’t.

Tourism is a rapidly growing economic activity in the Peruvian Amazon, the majority concentrated on its lakes and rivers. But, if well managed, it is also one of the few industries that is ecologically sustainable and that can bring much-needed revenues to Peru’s protected areas. Provided we understand and accept that, like us, giant otters need space and tranquility, my belief is that tourism and giant otter conservation can be compatible.

Mongabay: Why are education efforts with locals important for giant river otters?

Early morning on Cocha Salvador, Manu National Park. Photo by: Frank Hajek. |

Jessica Groenendijk: A large proportion of Peruvians living in cities and towns, even those in the rainforest like Puerto Maldonado or Iquitos, have little opportunity to experience nature first-hand, while for much of the remaining rural population the pressing struggle of day-to-day life precludes an appreciation or understanding of nature. The resulting negative human perceptions, often born of ignorance—that giant otters are dangerous, that cubs make fun pets, that populations are growing, and that they will eat one out of house and home—can only be modified by communication of the facts obtained through objective research. The importance of environmental education as a conservation tool is often underestimated, yet it is key to influencing human behaviors, with positive outcomes such as reducing human wildlife conflicts and promoting the conservation of biodiversity.

Mongabay: What measures would you like to see giant river otter countries take to save the species?

Jessica Groenendijk: I would like to see them create new protected areas and better manage existing ones, promote the giant otter as an ambassador of aquatic habitats in local education curricula, and generate funds for local giant otter research and conservation action.

Giant otter cubs waiting for the return of the group from a hunting foray. Photo by: Frank Hajek.

Boats used in artisanal gold mining. Photo by: Frank Hajek.

Aerial view of Amazon rainforest landscape scarred by open pit gold mining. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Aerial view of a muddy, mine waste-laden stream flowing into a rainforest river. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Aerial view of Cocha Sandoval in Peru, home to a well-known family of giant river otters. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Sunset on the Manu River. Photo by: Frank Hajek.

Related articles

High gold price triggers rainforest devastation in Peru

(10/11/2011) As the price of gold inches upward on international markets, a dead zone is spreading across the southern Peruvian rain forest. Tourists flying to Manu or Tambopata, the crown jewels of the country’s Amazonian parks, get a jarring view of a muddy, cratered moonscape … and then another … and another in what the country boasts is its capital of biodiversity. While alluvial gold mining in the Amazon is probably older than the Incas, miners using motorized suction equipment, huge floating dredges and backhoes are plowing through the landscape on an unprecedented scale, leaving treeless scars visible from outer space. Sources close to the Peruvian Environment Ministry say the government is considering declaring an environmental emergency in the region, but emergency measures passed two years ago were not enough to contain the destruction, and some observers doubt that a new decree would have any more impact.

Deforestation, climate change threaten the ecological resilience of the Amazon rainforest

(01/19/2012) The combination of deforestation, forest degradation, and the effects of climate change are weakening the resilience of the Amazon rainforest ecosystem, potentially leading to loss of carbon storage and changes in rainfall patterns and river discharge, finds a comprehensive review published in the journal Nature.

Ecotourism isn’t bad for wildlife in the Amazon

(11/23/2011) Ecotourism doesn’t hurt biodiversity, and in some cases may even safeguard vulnerable areas, concludes a new study from the Amazon in Mammalian Biology. Surveying large mammals in an ecotourism area in Manu National Biosphere, the researchers found that ecotourists had no effect on the animals. However, the researchers warn that not all ecotourism is the same, and some types may, in fact, hurt the very animals tourists come to see.

Loving the tapir: pioneering conservation for South America’s biggest animal

(09/11/2011) Compared to some of South America’s megafauna stand-out species—the jaguar, the anaconda, and the harpy eagle come to mind—the tapir doesn’t get a lot of love. This is a shame. For one thing, they’re the largest terrestrial animal on the South American continent: pound-for-pound they beat both the jaguar and the llama. For another they play a very significant role in their ecosystem: they disperse seeds, modify habitats, and are periodic prey to big predators. For another, modern tapirs are some of the last survivors of a megafauna family that roamed much of the northern hemisphere, including North America, and only declined during the Pleistocene extinction. Finally, for anyone fortunate enough to have witnessed the often-shy tapir in the wild, one knows there is something mystical and ancient about these admittedly strange-looking beasts.

Cameratraps take global snapshot of declining tropical mammals

(08/17/2011) A groundbreaking cameratrap study has mapped the abundance, or lack thereof, of tropical mammal populations across seven countries in some of the world’s most important rainforests. Undertaken by The Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring Network (TEAM), the study found that habitat loss was having a critical impact on mammals. The study, which documented 105 mammals (nearly 2 percent of the world’s known mammals) on three continents, also confirmed that mammals fared far better—both in diversity and abundance—in areas with continuous forest versus areas that had been degraded.

Climate change and deforestation pose risk to Amazon rainforest

(05/20/2011) Deforestation and climate change will likely decimate much of the Amazon rainforest, says a new study by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and the UK’s Met Office Hadley Centre. Climate change and widespread deforestation is expected to cause warmer and drier conditions overall, reducing the resistance of the rainforest ecosystem to natural and human-caused stressors while increasing the frequency of extreme rainfall events and droughts by the end of this century. While climate models show that higher temperatures resulting from global climate change will threaten the resilience of the Amazon, current deforestation is an immediate concern to the rainforest ecosystem and is likely driving regional changes in climate.

Demand for gold pushing deforestation in Peruvian Amazon

(04/19/2011) Deforestation is on the rise in Peru’s Madre de Dios region from illegal, small-scale, and dangerous gold mining. In some areas forest loss has increased up to six times. But the loss of forest is only the beginning; the unregulated mining is likely leaching mercury into the air, soil, and water, contaminating the region and imperiling its people. Using satellite imagery from NASA, researchers were able to follow rising deforestation due to artisanal gold mining in Peru. According the study, published in PLoS ONE, Two large mining sites saw the loss of 7,000 hectares of forest (15,200 acres)—an area larger than Bermuda—between 2003 and 2009.

First strike against illegal gold mining in Peru: military destroys miners’ boats

(02/21/2011) Around a thousand Peruvian soldiers and police officers destroyed seven and seized thirteen boats used by illegal gold miners in the Peruvian Amazon, reports the AFP. The move is seen as a first strike against the environmentally destructive mining. Used to pump silt up from the river-bed, the boats are essential tools of the illegal gold mining trade which is booming in parts of the Amazon.

Guyana bans gold mining in the ‘Land of the Giants’

(03/01/2010) Guyana has banned gold dredging in the Rewa Head region of the South American country after pressure from Amerindian communities in the area. A recent expedition to Rewa Head turned up unspoiled wilderness and mind-boggling biodiversity. The researchers, in just six weeks, stumbled on the world’s largest snake (anaconda), spider (the aptly named goliath bird-eating spider), armadillo (the giant armadillo), anteater (the giant anteater), and otter (the giant otter), leading them to dub the area ‘the Land of the Giants’. “During our brief survey we had encounters with wildlife that tropical biologists can spend years in the field waiting for. On a single day we had two tapirs paddle alongside our boat, we were swooped on by a crested eagle and then later charged by a group of giant otters.”

(11/29/2009) An expedition deep into Guyana’s rainforest interior to find the endangered giant river otter—and collect their scat for genetic analysis—uncovered much more than even this endangered charismatic species. “Visiting the Rewa Head felt like we were walking in the footsteps of Wallace and Bates, seeing South America with its natural density of wild animals as it would have appeared 150 years ago,” expedition member Robert Pickles said to Mongabay.com.