Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, 1988-2011. Photos by Rhett A. Butler.

The Brazilian Senate tonight passed controversial legislation that will reform the country’s 46-year-old Forest Code, which limits how much forest can be cleared on private lands. Environmentalists are calling the move “a disaster” that will reverse Brazil’s recent progress in slowing deforestation in the world’s largest rainforests.

The revised Forest Code — which passed the Senate 58-8 — reduces the amount of forest cover landowners are required to maintain and grants amnesty for farmers and ranchers who illegally cleared forest prior to July 2008. Those landowners — provided their properties are less than 400 hectares (988 acres) — won’t be required to replant forest to bring their land up to the legal requirement. Larger properties will have 20 years to come into compliance or can offset deforestation by renting or buying a nearby parcel of forest.

The new Forest Code maintains pre-existing forest cover requirements, which range from 20 percent in the drier cerrado to 80 percent in the Amazon rainforest, but landowners are now allowed to count compulsory forest cover along rivers and hillsides as part of their legal reserve. The revision also reduces the required margin along waterways from 30 meters (100 feet) to 15 meters (50 feet).

The revision is not yet law however. It still needs to be approved by lower house of Congress — where it is expected to pass easily — and President Dilma Rousseff who is under intense pressure from environmentalists to keep a campaign promise not to grant amnesty for past deforestation or let rainforest destruction rise. Rousseff however is likely to approve the measure next year, putting Brazil in an awkward position as host of Rio+20, a major environmental conference to be held in Rio de Janeiro in June. Environmentalists are planning to make the Forest Code a top campaign target ahead of the conference.

Accordingly, green groups immediately decried the changes.

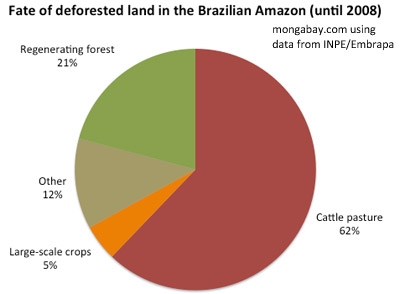

Fate of deforested land in the Brazilian Amazon until 2008. Low-intensity cattle ranching is the biggest driver of deforestation. Cattle are typically used as a proxy for speculating on land prices since ranching is the fastest and easiest way to informally claim forest land, which is considerably more valuable once cleared. |

“We’re at a time in history when the world seeks leadership in smart, forward-thinking development,” said WWF International Director-General Jim Leape. “Brazil was staking a claim to being such a leader. It will be a tragedy for Brazil and for the world if it now turns its back on more than a decade of achievement to return to the dark days of catastrophic deforestation.”

WWF estimates that the revised Forest Code will reduce forest cover in Brazil by 76.5 million hectares (295,000 square miles), an area larger than Texas.

But the powerful agricultural lobby that pushed the bill through the Senate claimed the new Forest Code would help protect the environment, while facilitating rapid agricultural expansion.

“Approval of this project ends the dictatorship represented by a half-dozen non-governmental organizations controlled by the Ministry of Environment and makes clear that the environmental question is for everybody,” Senator Katia Abreu, one of the strongest voices in supporting the bill, was quoted as saying by ABC.es.

“The environment is an essential part of agriculture. We are more dependent on nature than any other economic activity, and we want our forests to remain standing,” she added in a press release.

In making their case for reform, supporters of the bill said that because the Forest Code has been so widely flouted—more than 90 percent of landowners in the Amazon are operating illegally—a large component of the Brazilian economy is effectively “illegal”, undermining governance and efforts to improve land management.

But governance is predicated on the political will to enforce the law, which is largely lacking across much of the Amazon. Claudio Maretti, leader of WWF’s Living Amazon Initiative, doubts that the new code will be accompanied by sufficient law enforcement.

“The new draft does not make enforcement any easier,” he told mongabay.com prior to the passage of the bill. “It is more complicated, and has far too many exceptions. Nothing now seems to suggest that this version of the law will be better enforced.”

Language in the bill that passed today does seem to strengthen enforcement capacity, at least on paper, giving more power to the country’s environmental agency Ibama to investigate commodities produced in the Amazon.

The momentum to reform the Forest Code seemed to gather pace in part due to stepped-up law enforcement, including raids by Ibama and “blacklisting” of municipalities where deforestation was high. Blacklisted zones lost preferential access to credit until they complied with environmental laws. Facing with increased regulation, ranchers and farmers — especially in the state of Pará — launched a push to change the Forest Code. Now environmentalists fear the tide is turning against them, despite what they say is strong support from the public on stopping deforestation.

“80% of Brazilians are against the Code promoted by the rural sector – a project approved by 80% of the Chamber for Deputies,” said Greenpeace Amazon team leader Paulo Adario. “Dilma will need to choose between 80 percents – those of the Brazilian population or those of the Brazilian Congress.”

Roberto Smeraldi, the Director of Amigos da Terra – Amazônia Brasileira, added that the next 180 days would prove crucial in determining whether how the new Forest Code will impact forests in Brazil.

“One step backwards, with the amnesty, one step into the future, with an innovative package of economic instruments,” he told mongabay.com. This legislation will lead to a number of judicial conflicts as far as implementation is concerned: a clear example is the rural registry [that has] just one georeferenced coordinate. The next steps include monitoring how government will detail, in 180 days, the plan for economic instruments: unless they are solid and significant, the chances of meaningful implementation would be much reduced.”

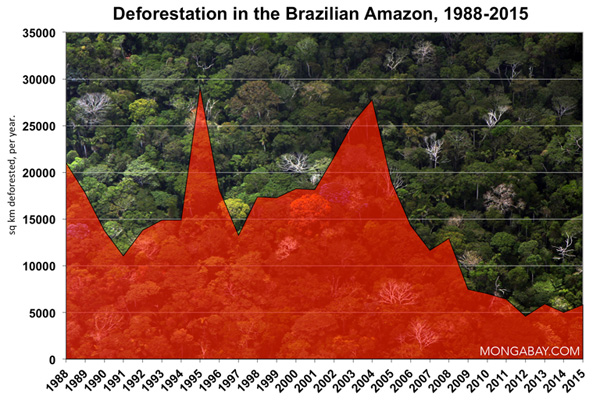

The vote to reform the Forest Code came a day after the Brazilian government released preliminary data showing that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon for the year ended July 2011 fell to the lowest level since annual record-keeping began in 1988. In 2009 then-president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva set a target to reduce deforestation 80 percent by the end of the decade under a national climate plan that would cut greenhouse gas emissions 39 percent from a projected 2020 baseline. Brazil is presently ahead of its deforestation-reduction goals, although some question how much of the reduction is due to government action, and how much is due to macroeconomic factors.

“Deforestation in Brazil remains a serious problem despite the fall in rates between 2005 and 2010. Only part of this decrease was the result of government programs or stricter enforcement of environmental laws,” eminent Amazon scientist Philip Fearnside wrote in an op-ed published last week in The Financial Times. “The main reason was that the international price of beef and soya fell from 2003 to 2007, and this was followed by the global economic collapse that began in 2008. Over that period, the Brazilian real almost doubled relative to currencies such as the US dollar. This cut the profits of commodity exporters deeply, as all their expenses remained in reals while their revenues were in diminished foreign currencies.”

“Such macroeconomic ‘windfalls’ can help contain deforestation, but they are only temporary.”

Related articles

Amazon rainforest loss in Brazil drops to lowest ever reported

(12/05/2011) Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell to the lowest level on record between August 2010 and July 2011 according to preliminary data from Brazil’s National Institute of Space Research (INPE).

Deforestation and forest degradation slows in Brazil’s Amazon since August

(12/02/2011) Deforestation and forest degradation are down moderately from August through October 2011 relative to the same period a year ago, reports a satellite-based assessment released today by Imazon. Imazon’s near-real time system found that 512 sq km of rainforest were cleared between Aug 2011 and Oct 2011, the first three months of the deforestation calendar year, which runs from August 1 through July 31. The figure represents a 4 percent decline from the 533 sq km cleared in 2010

Brazil plans $120 billion in infrastructure investments in the Amazon by 2020

(10/19/2011) Brazil’s push to expand infrastructure in the Amazon region will require at least 212 Brazilian reals ($120 billion) in public and private sector investment by 2020, reports Folha de Sao Paulo.

62% of deforested Amazon land ends up as cattle pasture

(09/04/2011) 62 percent of the area deforested in the Brazilian Amazon until 2008 is occupied by cattle pasture, reports a new satellite-based analysis by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and its Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa).