Selectively logged lowland forest in Indonesian Borneo. Photo by Rhett Butler

With old-growth forests fast diminishing and land prices surging across Southeast Asia due to high returns from timber and agricultural commodities, opportunities to save some of the region’s rarest species seem to be dwindling. But a new paper, published in the journal Conservation Letters, highlights an often overlooked opportunity for conservation: selectively logged forests.

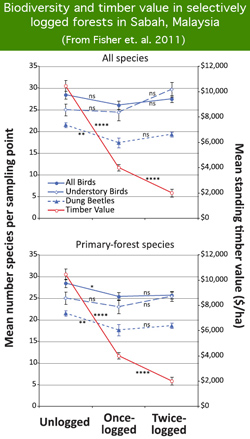

A number of studies have shown forests logged for only a few valuable tree species retain the majority of their biodiversity. The new paper, authored by Princeton University’s Brendan Fisher and others, confirmed this by analyzing the number of birds and dung beetles — considered good indicators of overall species richness — in logged and unlogged forests in Malaysian Borneo. The researchers then looked at financial returns of logging in the same forests.

Fisher and colleagues found that while the value of standing timber fell dramatically after one (60 percent drop) or two (80 percent drop) harvest cycles, the level of biodiversity fell by less than a quarter. The results suggest that selectively logged forests represent a cost-effective means for wildlife conservation: logged-over forests may be less expensive to acquire for protected areas and corridors to connect existing parks and reserves.

“Enlarging existing protected areas by acquiring logged

forests can ensure larger, more viable populations of

forest-dwelling species and reduce deleterious edge effects,” write the authors.

“Moreover, well-protected logged forests are likely

to recover over time and therefore represent not only important

current habitat for species, but also future habitat

for species that require mature forests and cannot tolerate

logged forests. For such species, maintaining connectivity

between logged forests and unlogged forests is likely to be

important in order to permit eventual dispersal into the

recovering logged forest.”

The findings are especially relevant in Asia because roughly 50 percent of forests in Malaysia and Indonesia are zoned for logging. While these “production forests” may be degraded, they do retain substantial amounts of biodiversity and provide ecosystem services like carbon sequestration, erosion control, and watershed maintenance.

The authors conclude with a careful warning not to misinterpret their results, lest loggers see the study as an opportunity to push for first-time logging of existing protected areas. They also caution that the study doesn’t justify abandonment of primary forests as a priority for conservation efforts.

Selectively logged forests house more biodiversity and store more carbon than conventionally logged forests, industrial agriculture, and plantations—including oil palm and pulp and paper estates. Photo by Rhett Butler. |

“The bird and dung beetle losses that occur during

logging are not trivial, and our results should not be

used to suggest that, by logging primary forests, governments

could gain huge financial profits at little cost to

biodiversity,” they write. “The logging of primary forests precipitates

a significant loss of biodiversity.”

“Beyond biodiversity, Southeast Asia’s lowland

dipterocarp forests provide numerous ecosystem services,

including carbon storage, regulation of river flows

and sedimentation, and a variety of aesthetic and cultural

benefits. In some cases, these ecosystem services

have quantifiable economic values, such that the logging

of primary forests will predicate (sometimes large) social

costs.”

CITATION: Brendan Fisher, David P. Edwards, Trond H. Larsen, Felicity A. Ansell, Wayne W. Hsu, Carter S. Roberts, & David S. Wilcove. Cost-effective conservation: calculating biodiversity and logging

trade-offs in Southeast Asia. Conservation Letters 0 (2011) 1–8

Related articles

Scientists call upon Indonesia to recognize value of secondary forests

(11/18/2010) A group of scientists have called upon the governments of Indonesia and Norway to recognize the conservation value of logged-over and “degraded” forests under their partnership on reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation. The letter urges the Indonesian government to extend protection to forest areas that may not be pristine but still serve as important carbon sinks, house endangered wildlife, and provide livelihoods for communities.

RSPO to recognize secondary forests as conservation priority

(11/12/2010) The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a body that sets environmental standards for palm oil production, has passed a resolution to reconfirm that secondary and degraded forests can classified as High Conservation Value (HCV) areas. The designation could increase the area of forest conserved within oil palm plantations provided it has high conservation significance, such as serving as habitat for endangered species like orangutans, Sumatran tigers, and rhinos.

Secondary forest should become new conservation initiative

(01/19/2009) “I want to convince you we need to go beyond primary forests to preserve biodiversity”, Robin Chazdon told an audience at the National Natural History Museum during a symposium on the tropics. Chazdon, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut, has been studying secondary growth forests for over eighteen years. Secondary forests are those forests in the process of regrowth after being used for agriculture or logging. In her study area of NE Costa Rica, many of these forests were converted to pastures in the 1970s and 1980s, but have since been abandoned. In her presentation Chazdon argued that to preserve biodiversity numerous types of human-impacted landscapes, such as secondary forest, require attention by the conservation community.

Destruction of old-growth forests looms over climate talks

(12/08/2009) Destruction of old-growth or primary forests looms large in discussions in Copenhagen over a scheme to compensate tropical countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD). Some environmental groups are pressing for conservation of old-growth forests — the most carbon-dense, and biologically-rich state of forests — to be the centerpiece of REDD, while industry and other actors are pushing for “sustainable forest management” or logging using reduced-impact techniques to be the primary focus of REDD.

Rainforest conversion to oil palm causes 83% of wildlife to disappear

(09/15/2008) Conversion of primary rainforest to an oil palm plantation results in a loss of more than 80 percent of species, reports a new comprehensive review of the impacts of growing palm oil production. The research is published in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

In the Amazon, primary forest biodiversity tops that of secondary forest, plantations

(11/12/2007) Plantations and secondary forests are no match for primary Amazon rainforest in terms of biodiversity, reports the largest ever assessment of the biodiversity conservation value in the tropics.