Tropical forest in Ghana, an irreplaceable habitat for many species. Photo courtesy of Ben Phalan.

Given that we have very likely entered an age of mass extinction—and human population continues to rise (not unrelated)—researchers are scrambling to determine the best methods to save the world’s suffering species. In the midst of this debate, a new study in Science, which is bound to have detractors, has found that setting aside land for strict protection coupled with intensive farming is the best way to both preserve species and feed a growing human world. However, other researchers say the study is missing the point, both on global hunger and biodiversity.

While many factors are behind the decline in global species, the biggest is habitat loss, with natural ecosystems usually losing out to agricultural expansion. This situation has led to a debate among researchers known as “land sparing versus land sharing”. Land sparing argues the best way to conserve species is to set aside as much intact ecosystems as possible, while intensively growing crops on remaining land. Land sharing, however, argues that agriculture should forgo industrialization and become more biodiversity-friendly, allowing species to survive in a mix of forests and less-impact agriculture. According to the new study, land sparing achieves a better result for biodiversity than seeing land as both a reservoir for agriculture and species.

“It would be nice to think that we could conserve species and produce lots of food, all on the same land,” said study author, Malvika Onial from the University of Cambridge, in a press release. “But our data from Ghana and India show that’s not the best option for most species. To produce a given amount of food, it would be better for biodiversity to farm as productively as possible, if that allows more natural habitat to be protected or restored.”

Researchers argue that high-yielding oil palm plantations like this one in Ghana could potentially help the country to meet its food needs without clearing more forests. As an intensive monoculture, palm oil plantations harbor little biodiversity and have been blamed for vast deforestation across Southeast Asia. Image courtesy of Ben Phalan. |

The study measured populations of 341 bird species and 260 trees in Ghana and India across “remnants of forest within a matrix of farmland ranging from diverse low-yielding mosaic agriculture to large-scale high-yielding monocultures.”

The results, they say, were unambiguous: species would have the largest populations—and therefore be the furthest from extinction—if farming was kept to a minimal amount of land growing high yields, while natural habitat was set aside. The results worked both for rare and common species.

“Farmland with some retained natural vegetation had more species of birds and trees than high-yielding monocultures of oil palm, rice or wheat but produced far less food energy and profit per hectare,” explains lead author Dr Ben Phalan from the University of Cambridge. “As well as requiring more land to produce the same amount of food, the ‘wildlife-friendly’ farmlands were not as wildlife-friendly as they first appeared. Compared with forest, they failed to provide good habitat for the majority of bird and tree species in either region.”

However, the authors caution that their study should not be taken as one-size-fits-all, since it only looked at two regions—southwest Ghana and northern India—and two types of species, birds and trees.

Still with these findings in hand, the researchers conclude that India and Ghana “could produce more food with minimal further negative impacts on forest species if they were to implement ambitious programs of forest protection and restoration alongside sustainable increases in agricultural yield, but they could not if they adopted land sharing.”

William Laurance, a tropical forest scientist with James Cook University, told mongabay.com that the study makes a good point, although there are caveats.

Coffee beans in Sao Tome and Principe islands. |

“Broadly speaking, I’m inclined to agree with the authors’ conclusions,” Laurance says. “However, there’s a lot of local variation in land-use practices across the tropics that could influence whether land-sharing or land-sparing is the best alternative. Land-sparing can be difficult to achieve in some regions—for instance, many protected areas in the tropics, which are supposed to be spared from development, are suffering from various forms of encroachment. So, the decision of whether to favor land-sparing or land-sharing may well depend on the local context, though when it’s feasible I do believe a land-sparing approach will generally be superior for biodiversity.”

The authors of the study agree with Laurance that their results are “not enough to argue that land sparing is the optimal strategy for reconciling food production and biodiversity conservation everywhere and for all taxa,” according to their paper. But they argue that similar studies should be conducted elsewhere to strike the right balance between land sharing and land sparing.

However, not every researcher believes that this debate is the right one for biodiversity or for feeding the world. Ivette Perfecto, who has spent her career studying how farmers can work with nature instead of against it, says that focusing on land sharing versus land sparing entirely misses the point on global hunger.

“The problem of hunger and starvation in the world is largely a consequence of access to food that is already available, and increasing per hectare productivity especially in large-scale monocultures is not likely to change this problem, which is fundamentally a socioeconomic and political one,” Perfecto told mongabay.com, adding that, “the need to feed the world should not be used as an excuse to continue with an agricultural model that degrades the environment and has failed to eliminate hunger in the world.”

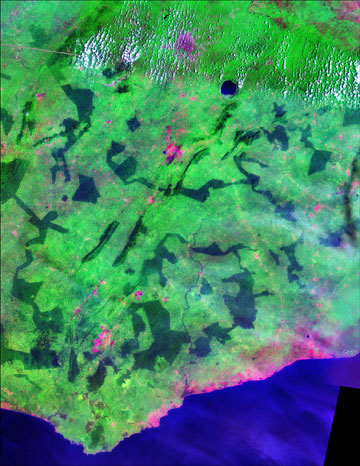

Satellite image of southwest Ghana, showing remaining forests (dark green) and land which has been cleared for agriculture (bright green). The paper by Phalan et al. examines how food production might be increased in this region with the least harm to biodiversity. The width of the image is around 200 km. Image by NASA. |

As of 2009 a billion people in the world—the most in history—suffered from hunger, despite the fact that there is more than enough food to go around, according to Perfecto.

She says that when it comes to hunger and biodiversity, small-scale farms that practice agroecology—applying ecological principles to growing crops—have in fact been shown as incredibly effective, both in tackling food problems and preserving species and ecosystem services.

“Food production in smallholder farms is the key to food security and to the conservation of biodiversity. Increasing food production locally, where the poor live, can be accomplished using agroecological methods that can promote biodiversity both within farming systems and at the landscape level,” says Perfecto, who adds that industrial agriculture does not necessarily mean other land will be spared, instead her research has shown that industrial agriculture “frequently leads to more deforestation and loss of biodiversity.” In other words large-scale commercial agriculture simply begets more large-scale commercial agriculture, devastating ecosystems and species in the process.

Study author, Rhys Green from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and the University of Cambridge, says that their Science study is not meant to grant carte blanche to industrialized agriculture.

“High-yielding organic farming and other systems such as agroforestry can be a useful component of a land sparing strategy and may offer the additional advantage of fewer adverse effects of farming from fertilizers and pesticides,” he admits. “But whatever the farming system, protection of natural habitats will continue to be essential for the conservation of many species.”

But Perfecto argues that the land sparing argument tacitly accepts the need for large-scale industrialized agriculture.

“The land sparing/land sharing debate is a false debate proposed by those who wish to justify the continuation of industrial agriculture,” she told mongabay.com “Those of us that ‘argue for ‘land sharing” or wildlife-friendly farming recognize the importance of maintaining natural habitat and argue that there is no need to destroy more natural habitat in order to produce enough food to feed the world.”

|

Comments from Ben Phalan, lead author of the study after the article was published: I’d like to respond to some of the criticisms here. We agree that solving hunger is about far more than increasing food production. But it is food production which affects biodiversity. Our conclusion that land sparing would be a better option than land sharing holds even if total production could be frozen or substantially reduced (see figure 2 of our paper). Therefore, arguing against our conclusion on the grounds that total production could be frozen or cut does not stack up. |

Organic farm in Indonesian Borneo. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Village, rice fields, and forest in Madagascar. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Intensive agriculture meets natural habitat: soy fields and the Amazon rainforest in Brazil. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Related articles

How an agricultural revolution could save the world’s biodiversity, an interview with Ivette Perfecto

![]()

(05/04/2010) Most people who are trying to change the world stick to one area, for example they might either work to preserve biodiversity in rainforests or do social justice with poor farmers. But Dr. Ivette Perfecto was never satisfied with having to choose between helping people or preserving nature. Professor of Ecology and Natural Resources at the University of Michigan and co-author of the recent book Nature’s Matrix: The Link between Agriculture, Conservation and Food Sovereignty, Perfecto has, as she says, “combined her passions” to understand how agriculture can benefit both farmers and biodiversity—if done right.

Innovative program saves wildlife, protects forests, and fights poverty in Africa

(08/23/2011) Luangwa Valley in Zambia is home to stunning scenes of Africa wildlife: elephants, antelopes, zebra, buffalo, leopards, hyena, and lions all thrive in Luangwa’s protected areas, while the Luangwa River is known for multitude of snapping crocodiles and its superabundant herds of hippos. In fact, the area’s hippos were filmed for the BBC’s program Life, including a dramatic battle between two males (see below). Yet as in many such places in Africa, abundant plains and forest wildlife bump up against the needs of impoverished local people. The resulting conflict usually ends in large-scale wildlife declines; the same trend was documented in the Luangwa Valley until a unique initiative began to make a difference not only in the life of animals, but of people as well.

Balancing agriculture and rainforest biodiversity in India’s Western Ghats

(08/08/2011) When one thinks of the world’s great rainforests the Amazon, Congo, and the tropical forests of Southeast Asia and Indonesia usually come to mind. Rarely does India—home to over a billion people—make an appearance. But along India’s west coast lies one of the world’s great tropical forests and biodiversity hotspots, the Western Ghats. However it’s not just the explosion of life one finds in the Western Ghats that make it notable, it’s also the forest’s long—and ongoing—relationship to humans, lots of humans. Unlike many of the world’s other great rainforests, the Western Ghats has long been a region of agriculture. This is one place in the world where elephants walk through tea fields and tigers migrate across betel nut plantations. While wildlife has survived alongside humans for centuries in the region, continuing development, population growth and intensification of agriculture are putting increased pressure on this always-precarious relationship. In a recent paper in Biological Conservation, four researchers examine how well agricultural landscapes support biodiversity conservation in one of India’s most species-rich landscapes.

Foreign big agriculture threatens world’s second largest wildlife migration

(03/07/2011) As the world’s largest migration in the Serengeti plains—including two million wildebeest, zebra, and Thomson’s gazelles—has come under unprecedented threat due to plans for a road that would sever the migration route, a far lesser famous, but nearly as large migration, is being silently eroded just 1,370 miles (2,200 kilometers) north in Ethiopia’s Gambela National Park. The migration of over one million white-eared kob, tiang, and Mongalla gazelle starts in the southern Sudan but crosses the border into Ethiopia and Gambela where Fred Pearce at Yale360 reports it is running into the rapid expansion of big agribusiness. While providing habitat for the millions of migrants, Gambela National Park’s land is also incredibly fertile enticing foreign investment.

Greening the world with palm oil?

(01/26/2011) The commercial shows a typical office setting. A worker sits drearily at a desk, shredding papers and watching minutes tick by on the clock. When his break comes, he takes out a Nestle KitKat bar. As he tears into the package, the viewer, but not the office worker, notices something is amiss—what should be chocolate has been replaced by the dark hairy finger of an orangutan. With the jarring crunch of teeth breaking through bone, the worker bites into the “bar.” Drops of blood fall on the keyboard and run down his face. His officemates stare, horrified. The advertisement cuts to a solitary tree standing amid a deforested landscape. A chainsaw whines. The message: Palm oil—an ingredient in many Nestle products—is killing orangutans by destroying their habitat, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Agricultural innovation will reduce poverty, help stabilize climate change according to new report

(01/12/2011) With nearly a billion people people going hungry in the world today as 40 percent of the global food stock is wasted before it is consumed, many are seeking ways to increase the efficiency of the world’s food system. Worldwatch Institute, an environmental sustainability and social welfare research organization, today released State of the World 2011: Innovations that Nourish the Planet, which highlights recent successes in agricultural innovation and outlines ways to reduce global hunger and poverty while at the same time minimizing the impact of agriculture on the environment.

Farms in the sky, an interview with Dickson Despommier

(10/12/2010) To solve today’s environmental crises—climate change, deforestation, mass extinction, and marine degradation—while feeding a growing population (on its way to 9 billion) will require not only thinking outside the box, but a “new box altogether” according to Dr. Dickson Despommier, author of the new book, The Vertical Farm. Exciting policy-makers and environmentalists, Despommier’s bold idea for skyscrapers devoted to agriculture is certainly thinking outside the box.

Could forest conservation payments undermine organic agriculture?

(09/07/2010) Forest carbon payment programs like the proposed reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) mechanism could put pressure on wildlife-friendly farming techniques by increasing the need to intensify agricultural production, warns a paper published this June in Conservation Biology. The paper, written by Jaboury Ghazoul and Lian Pin Koh of ETH Zurich and myself in September 2009, posits that by increasing the opportunity cost of conversion of forest land for agriculture, REDD will potentially constrain the amount of land available to meet growing demand for food. Because organic agriculture and other biodiversity-friendly farming practices generally have lower yields than industrial agriculture, REDD will therefore encourage a shift toward from more productive forms of food production.

80% of tropical agricultural expansion between 1980-2000 came at expense of forests

(09/02/2010) More than 80 percent of agricultural expansion in the tropics between 1980 and 2000 came at the expense of forests, reports research published last week in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The study, based on analysis satellite images collected by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and led by Holly Gibbs of Stanford University, found that 55 percent of new agricultural land came at the expense of intact forests, while 28 percent came from disturbed forests. Another six percent came from shrub lands.