Focused conservation efforts, including reintroduction of captive individuals into the wild, have saved the golden lion tamarin from extinction. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

Don’t despair: that’s the message of a new paper in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, which argues that decades of conservation actions at multiple scales have had a positive impact for many of the world’s endangered species. While such actions have not yet turned back the tide of the current mass extinction crisis, they have achieved notable successes which often get lost in the gloom-and-doom news stories on biodiversity declines.

According to the paper, conservation actions take place on three scales. Microscale conservation focuses on a single species or ecosystem; mesoscale means conservation cooperation between a number of countries, such as efforts to curb the illegal wildlife trade or protect wide-ranging species; and finally macroscale means global organizations or campaigns, such as those that pressure multinational corporations to become more biodiversity-friendly.

Conservation success stories

National protected areas, which occur at the micro-scale, have been one of conservationists’ most notable achievements. Today, over 100,000 protected areas—national parks, wildlife refuges, game reserves, marine protected areas (MPAs), wildlife sanctuaries, etc.—cover some 7.3 million square miles (19 million kilometers). The paper points to a park in Central Asia as an example of how protected areas aid threatened species.

Without large conservation efforts, the world’s most abundant rhino would today be extinct. The white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) fell to just around 100 individuals (and was thought extinct until these were found), but today numbers 17,500, making this species among the world’s most upbeat conservation stories. Unfortunately, this species is still heavily poached. It is listed as Near Threatened. Photo by: Ikiwaner. |

“Following the establishment of Bardia National Park in Nepal […] the density of wild ungulates increased fourfold in just 22 years. This spike in prey base triggered increases in both endangered tiger (Panthera tigris) and threatened leopard (Panthera pardus) densities,” the authors write.

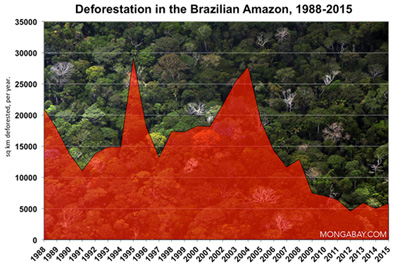

Protected areas have also gone a long way in curbing deforestation, especially in the Brazilian Amazon.

“An estimated 37 percent of the decline in annual deforestation rates in Brazil between 2002 and 2009 can be attributed to the preservation of 709,000 square kilometers of forest in newly established PAs,” according to the paper.

The paper acknowledges that many protected areas do are simply ‘paper parks’, i.e. while they are designated under protection, the reserves lack the funds and personnel needed from the government to keep people from illegally cutting trees, hunting species, and other impacts. In addition, simply conserving habitat is not enough to save many species.

“[Conservation] interventions such as rehabilitation, reforestation, reintroduction, population augmentation and invasive species eradication” are sometimes necessary, the authors write. In the UK, the large blue butterfly (Maculinea arion) was brought back from local extinction by reintroduction of individuals, restoration of habitat, and on-going management. Similar focused multi-faceted efforts have saved a number of species worldwide from extinction, such as the Seychelles magpie robin (Copsychus sechellarum) and the blue iguana (Cyclura lewisi).

Mesoscale conservation actions—which occur between different nations—have also been successful. One way this occurs is through protected areas that extend across national boundaries, with the goal to protect whole ecosystems and key species.

|

“Adjoining national parks established in the Virunga landscape of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Rwanda have led to population increases of elephants and gorillas,” the authors write, “the population of mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) has increased from 250 to 480 animals over the past 30 years.”

The paper also points to a recent agreement between all tiger countries to double wild tiger populations within a decades as an apt example of how mesoscale conservation works.

The largest conservation actions, however, take place on the world stage. Increasingly common, macroscale efforts have recently targeted multinational corporations that have been found to be responsible to biodiversity loss, especially the destruction of forests. Pressure from activist groups and consumers have pushed a number of big companies to change their ways. The study points to macroscale action having positive impacts on the cattle and soy industries in the Amazon, pulp and paper in Sumatra, and illegal logging in Madagascar as just a few examples.

“Public pressure by consumers in developed countries is sometimes needed to make a conservation difference thousands of miles away. This pressure, often in the form of boycotts of products obtained via deforestation, is transforming supply chains,” the authors note, adding that new technology, such as Google Earth, is also making it easier to track deforestation and connect it rapidly to companies on the ground.

Global activism on how commodities are produced is even hitting financial institutions.

“The decision by multinational banks, such as Citigroup, not to sanction loans to unscrupulous forestry projects and to require rigorous verification of eco-certification will benefit biodiversity,” the authors write.

Humpback whale breaching in Alaska. Conservation efforts have been instrumental in allowing many whale species to rebound after nearing extinction, including the humpback whale. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Beyond corporations, some governments have also added new regulations that are expected to help biodiversity worldwide. The US and EU have recently put laws on the docket that make buying or selling timber that was harvested illegally in its country of origin a federal offense. Australia is considering similar legislation.

The paper further argues that global organizations such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), which evaluates species for how endangered they are, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which determines the legality of species trade, have been boons to conversation efforts and biodiversity overall, even if imperfect—underfunded or poorly enforced—at times. In the same vein, the authors are optimistic that the UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD), which intends to pay countries to preserve standing forest, has a capacity to play a similar role.

“If carefully targeted, REDD investments could help to preserve biodiversity ‘hotspots’ with many endangered species,” they write.

In the end, conservation is about preserving life on Earth and successes should be celebrated. According to the paper, at least 16 birds from 5 continents would have gone extinct between 1994 and 2004 if not for direct conservation action. In addition the paper notes that a large number of iconic species—from bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) to golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia), and Pacific gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) to the Arabian oryx (Eschrichtius robustus)—have been saved by concentrated efforts at different scales. While it’s difficult to determine just how many species have been saved from extinction by conservation actions—from protected areas to global agreements—its hard to imagine how animals like tigers, elephants, gorillas, and pandas could have survived the past century without conservationists’ unflagging help, at times in the midst of overwhelming threats.

Miles to go before I sleep…

The paper, however, does not argue that conservationists should grow complacent—quite the opposite, instead, they argue, “conservationists should pat themselves on the back and then redouble their efforts at all conservation scales.”

Rainforest in Borneo. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

The researchers write that “more conservation projects fail than succeed, and our highlighting of successes here should not be taken as a call to rest on our laurels. Instead, our aim is to engender hope and inspire others to continue their dedicated efforts.” They recommend that conservation not only gain strength from past successes, but also learn what works and monitor both success and failure for the future.

“Fortunately, an increasingly large array of tools now exists to evaluate conservation projects. Results from both successful and unsuccessful conservation projects should be widely disseminated so that future successes can be repeated,” the authors write, stating that long-term funding and clear goals are vital to success.

The researchers conclude that conservation will only become more challenging in the future.

“With the global population expected to surge past 10 billion people by the end of this century, conservationists will face increasing challenges and a need for more funding and political and popular support,” they write.

While the war to save the diverse life on Earth hasn’t been won yet, some notable battles may point the way.

NOTE: Lead author of the paper, Navjot Sodhi, recently passed away.

DISCLOSURE: Rhett A. Butler, founder of mongabay.com, was a co-author of this paper

CITATION: Navjot S. Sodhi, Rhett Butler, William F. Laurance and Luke Gibson. Conservation successes at

micro-, meso- and Trends in Ecology and Evolution xx (2011) 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2011.07.002.

Related articles

Protected areas not enough to save life on Earth

(08/03/2011) Since the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 protected areas have spread across the world. Today, over 100,000 protected areas—national parks, wildlife refuges, game reserves, marine protected areas (MPAs), wildlife sanctuaries, etc.—cover some 7.3 million square miles (19 million kilometers), mostly on land, though conservation areas in the oceans are spreading. While there are a number of reasons behind the establishment of protected areas, one of the most important is the conservation of wildlife for future generations. But now a new open access study in Marine Ecology Progress Series has found that protected areas are not enough to stem the loss of global biodiversity. Even with the volume of protected areas, many scientists say we are in the midst of a mass extinction with extinction levels jumping to 100 to 10,000 times the average rate over the past 500 million years. While protected areas are important, the study argues that society must deal with the underlying problems of human population and overconsumption if we are to have any chance of preserving life on Earth—and leaving a recognizable planet for our children.

Decline in top predators and megafauna ‘humankind’s most pervasive influence on nature’

(07/14/2011) Worldwide wolf populations have dropped around 99 percent from historic populations. Lion populations have fallen from 450,000 to 20,000 in 50 years. Three subspecies of tiger went extinct in the 20th Century. Overfishing and finning has cut some shark populations down by 90 percent in just a few decades. Though humpback whales have rebounded since whaling was banned, they are still far from historic numbers. While some humans have mourned such statistics as an aesthetic loss, scientists now say these declines have a far greater impact on humans than just the vanishing of iconic animals. The almost wholesale destruction of top predators—such as sharks, wolves, and big cats—has drastically altered the world’s ecosystems, according to a new review study in Science. Although researchers have long known that the decline of animals at the top of food chain, including big herbivores and omnivores, affects ecosystems through what is known as ‘trophic cascade’, studies over the past few decades are only beginning to reveal the extent to which these animals maintain healthy environments, preserve biodiversity, and improve nature’s productivity.

Ocean prognosis: mass extinction

(06/20/2011) Multiple and converging human impacts on the world’s oceans are putting marine species at risk of a mass extinction not seen for millions of years, according to a panel of oceanic experts. The bleak assessment finds that the world’s oceans are in a significantly worse state than has been widely recognized, although past reports of this nature have hardly been uplifting. The panel, organized by the International Program on the State of the Ocean (IPSO), found that overfishing, pollution, and climate change are synergistically pummeling oceanic ecosystems in ways not seen during human history. Still, the scientists believe that there is time to turn things around if society recognizes the need to change.