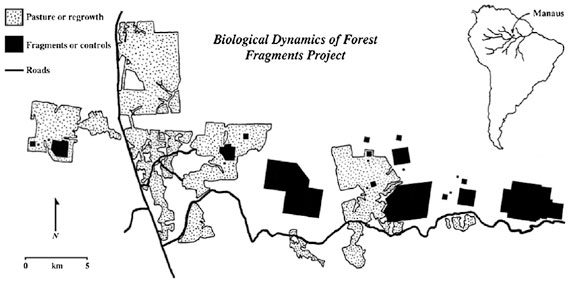

Forest fragments under research in the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project. Photo by: Richard Bierregaard.

For over 30 years, hundreds of scientists have scoured eleven forest fragments in the Amazon seeking answers to big questions: how do forest fragments’ species and microclimate differ from their intact relatives? Will rainforest fragments provide a safe haven for imperiled species or are they last stand for the living dead? Should conservation focus on saving forest fragments or is it more important to focus the fight on big tropical landscapes? Are forest fragments capable of regrowth and expansion? Can a forest—once cut-off—heal itself? Such questions are increasingly important as forest fragments—patches of forest that are separated from larger forest landscapes due to expanding agriculture, pasture, or fire—increase worldwide along with the human footprint.

The Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project (BDFFP)—begun in 1979—has started to provide general answers to these questions. As the world’s longest-running and largest study of forest fragments in the world, it has more than any other area given tropical ecologists’ a sense of how forest fragments, both big and small, function. Located fifty miles (80 kilometers) north of Manaus, Brazil, the study encompasses eleven fragments, spanning from 1 hectare to 100 hectares.

“The study is very ambitious in scope, covering just about every major group of organisms. We’ve studied everything from trees to tamarins, and army ants to antbirds,” says Dr. William F. Laurance, an ecologist at James Cook University, in a recent interview with mongabay.com. His colleague Dr. Thomas Lovejoy, biodiversity chair at the Washington DC-based Heinz Center for Science, Economics and the Environment, adds that in 32 years the research area has produced an astounding 581 publications.

A black-headed night monkey (Aotus nigriceps), which can be found in the project area. Photo by: Finding Species. |

Studies in the region have made clear delineations between forest fragments winners (for example some rodents and light-loving butterflies) and losers (mammals with big ranges and certain birds), have documented loss of carbon due to mortality of big trees, and have shown that no fragment is the same—size makes all the difference and fragments are constantly changing due to age or events such as droughts and windstorms.

“In many ways we’re still scratching the surface. We know very little about how fragmentation affects key ecological interactions among species. And many changes are likely to take a long time to become manifest, such as changes in the community composition of trees, some of which can live for a millennium or longer. Further, we have only a rudimentary idea of how fragmentation will affect species that live up in the forest canopy, or below ground in the soil,” Laurance says.

Research from the BDFFP has proven important for conservation decisions, says Lovejoy.

“One of the interesting things is the very existence of the project influenced the size of protected areas being created. And protected areas have tended to be even larger in recent years.”

In an age of climate change and mass extinction, forest fragments—even though they are inherently degraded—are vital conservation pieces. Many of the world’s great tropical forests, such as the Atlantic Forest of coastal Brazil and the Western Ghats of India, almost solely survive in fragments.

While forest fragments may never be returned to their original state, the BDFFP project has found hope that forests may be ‘bandaged’. In other words, improvements on their management, including corridors between forests, may see a rise in biodiversity and ecosystem services. Sometimes, says Lovejoy, human restoration can make a big difference.

“The biggest problem is that many of the forest canopy tree species have very large seeds that require a rodent to disperse them. So the bigger the area the more slowly the forest succession takes place. This can be hastened by actual planting of trees as was done in the 19th century for the Tijuca Forest in Rio de Janeiro—now the largest urban forest in the world.”

In an August 2011 interview William Laurance and Thomas Lovejoy discuss the milestones from the world’s longest study of tropical forest fragments, how forest fragments in the Amazon function, and the place of forest fragments in conservation efforts worldwide.

INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM LAURANCE AND THOMAS LOVEJOY

Map of the site of the The Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project (BDFFP). Map courtesy of: W.F. Laurance et al. / Biological Conservation 144 (2011) 56–67.

Mongabay: What makes this study notable?

William Laurance: Three things. First, it’s been running continuously for 32 years, which is no mean feat. Long-term datasets like this are incredibly valuable. Second, it’s really big in scale, about a thousand square kilometers [386 square miles]. This makes our findings directly relevant to real-world landscapes. Finally, the study is very ambitious in scope, covering just about every major group of organisms. We’ve studied everything from trees to tamarins, and army ants to antbirds.

William Laurance in Panama. Photo by: Marcos Guerra. |

Thomas Lovejoy: We were delighted to learn that the study is the most productive scientifically in the entire Amazon-Andes (581 publications to date), and it is the most widely cited tropical field study (both of those were independent analyses). In addition, we have produced something like 140 PhDs and Masters “graduates” of which more than half are Brazilian.

Mongabay: The study site is in the Brazilian Amazon. What does the site look like? How many fragments, what sizes?

William Laurance: We have 11 fragments ranging from 1 to 100 hectares in area. The modified vegetation surrounding them is a mosaic of cattle pasture and regrowth forest. And surrounding all this is a large expanse of old-growth forest, which we use as our “control sites”, that extends all the way north to Venezuela. In many ways our study area is still very wild. We often encounter jaguars, tapirs and harpy eagles, for instance. Sensitive species like these don’t last very long once you start getting significant human encroachment and hunting.

Thomas Lovejoy: It’s very exciting that we have an active Harpy Eagle nest 200 meters from one of our camps.

FRAGMENTS

Mongabay: What has the study discovered about how forest fragments work differently than intact forest?

Thomas Lovejoy. Photo courtesy of Thomas Lovejoy. |

William Laurance: Fragments change in a lot of ways. They are hyper-disturbed relative to intact forest, and tend to lose ecological specialists at the expense of more-generalized species. Their architecture and microclimate are quite profoundly altered because tree mortality and canopy damage are often heavy. Edge effects are a big driver of these changes, which are ongoing.

Thomas Lovejoy: Fragments lose up to 30 percent of their biomass essentially forever because of the vulnerability of big trees to windthrow [when trees are toppled or broken by wind].

Mongabay: How is biodiversity impacted by forest fragmentation? What role does fragment size play?

William Laurance: Some groups suffer more from fragmentation than others. The biggest losers are things like many understory insectivorous birds; specialized animals that avoid the surrounding pastures and regrowth; and larger mammals that need large expanses of forest. Some other groups, such as rodents and certain frogs, don’t suffer as much. And a few groups, like generalist shrub-feeding bats and light-loving butterflies, increase dramatically in fragmented landscapes.

Thomas Lovejoy: Hundred hectare fragments lose half of the forest interior bird species in less than 15 years.

Mongabay: Are fragmented forests more at risk of hunting?

William Laurance: We try to control hunting in our study area, but in most tropical landscapes hunting increases dramatically [in fragmented forests] and that also tends to a key force in driving species declines and even local extinctions.

Thomas Lovejoy: The Instituto Chico Mendes has recently added someone to be responsible for our reserves (which are legal Brazilian national protected areas) and regular patrols are beginning.

William Laurance: Fragment size is a really critical factor. Small fragments (those under 10 hectares in size) are really hammered by edge effects and lose much of their biodiversity. They’re sort of like biological deserts, and very seriously distorted ecologically-just a caricature of intact forest.

Mongabay: What is edge-effect? How does this impact fragments in the study?

Another view of fragments in project area. Photo by: Richard Bierregaard. |

William Laurance: Edge effects are diverse ecological changes associated with the abrupt, artificial boundaries of forest fragments. They are incredibly diverse, involving everything from exotic species invasions to microclimatic alterations to elevated mortality of big, ancient rainforest trees.

Thomas Lovejoy: The deforested areas are sunlit and hot during the day and this affects the microclimate at the edge of the forest.

Mongabay: How does fragmentation affect carbon sequestration?

William Laurance: Carbon storage definitely declines in fragmented forests because a lot of the big, old trees, which store much of the forest’s carbon, die because of increased wind turbulence and desiccation stress within a few hundred meters of forest edges. As it decomposes, much of that carbon enters the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, thereby likely contributing to global warming. There’s also an increase in wood debris and small pioneer trees in fragments. These store some carbon but a lot less than the big trees that occurred there originally.

Mongabay: Many of the areas around the fragments in your study have begun to transition from pasture to secondary forest. What changes have occurred in the fragments due to this?

William Laurance: Some species that utilize the regrowth and had formerly disappeared from the fragments, such as certain monkey, beetle and understory bird species, have now recolonized fragments encircled by regrowth. In addition, the microclimatic stresses in these fragments are lessened, as the regrowth helps to buffer the fragment from winds and heat. Finally, many of the trees regenerating in the fragments are generalist pioneer species that thrive in the surrounding secondary forest. The fruits of these species are carried into fragments by generalist fruit-eating bats and birds.

Mongabay: What has been the most surprising result from this decades-long study?

Frog in the Phyllomedusa genus from the project area. Photo courtesy of William Laurance. |

William Laurance: Whew, that’s a hard one. I don’t think we were expecting to see such a dramatic collapse of biomass and carbon in the fragments. And I think we’ve been surprised at how dynamic the landscape is, which largely reflects the changing modified vegetation surrounding the fragments. Finally, we’ve been really struck by the importance of intense rare events, such as major windstorms and droughts. These have really altered the ecologies of the fragments, much more than that of the nearby intact forest.

Thomas Lovejoy: One of the important very early results is that there is a refugee effect as forest interior species flee into the remaining forest fragment; that is superimposed on the effect of fragmentation itself. We were also surprised by the increase in butterfly diversity until we realized it was light-loving species becoming abundant in the surrounding pastures and then invading the forest patches, affecting forest interior butterfly species.

Mongabay: What questions still remain unanswered about the forest fragments?

William Laurance: In many ways we’re still scratching the surface. We know very little about how fragmentation affects key ecological interactions among species. And many changes are likely to take a long time to become manifest, such as changes in the community composition of trees, some of which can live for a millennium or longer. Further, we have only a rudimentary idea of how fragmentation will affect species that live up in the forest canopy, or below ground in the soil.

Thomas Lovejoy: Originally the project was planned to run for 20 years, but of course we had no real idea of rates of change in advance. It is clear that the 100 hectare plots will continue to change over hundreds of years. In addition because long term data sets are so valuable—and make it possible to answer questions not part of the original project design—we are in the process of institutionalizing it.

CONSERVATION

Black-headed antbird (Percnostola rufifrons) from the project. Photo courtesy of: William Laurance.

Mongabay: How should the study’s findings impact conservation efforts in the Amazon?

William Laurance: We’ve long tried to link our findings to real-world conservation. We spend a lot of time and effort training Amazonian students and environmental decision-makers Some of these have gone on to have very influential and successful careers. We also have engaged in a whole string of major debates about the future of the Amazon, with respect to things like road and infrastructure expansion, protected areas, ecological zoning and climate change.

Thomas Lovejoy: One of the interesting things is the very existence of the project influenced the size of protected areas being created. And protected areas have tended to be even larger in recent years.

William Laurance: We made headlines around the world with our 2001 Science study that showed just how badly the tidal wave of planned infrastructure could impact the region, and we’re still fighting quite desperately to save our study area in central Amazonia, which is increasingly in danger of being overrun by poorly planned development and forest colonization projects.

Thomas Lovejoy: We are in a region of a proposed Central Amazonian Corridor so we will continue to try and build on that concept.

Mongabay: Is connecting fragments worth the time and funds needed?

William Laurance: I think it is in landscapes where the forest has already largely disappeared, such as in the imperiled Brazilian Atlantic forest. In such cases it’s definitely worth the effort and expense.

Thomas Lovejoy: Also as one thinks about species responding to climate change, corridors become ever more important.

Mongabay: How do these forests ‘recover’? What can people do to ensure such recovery?

William Laurance: They can recover partially, but not fully, in my view. Corridors have been likened to ‘bandages for wounded landscapes’. The wound can partially heal with a good bandage, but not completely.

Thomas Lovejoy: The biggest problem is that many of the forest canopy tree species have very large seeds that require a rodent to disperse them. So the bigger the area the more slowly the forest succession takes place. This can be hastened by actual planting of trees as was done in the 19th century for the Tijuca Forest in Rio de Janeiro—now the largest urban forest in the world.

Mongabay: Do you think fragmentation in other tropical forests, for example in Africa and Asia, look similar (and therefore lead to similar lessons)?

Harpy eagle in project area. Photo courtesy of William Laurance. |

William Laurance: There are both similarities and differences. The Asian forests are rather different in being dominated by dipterocarp trees, which are mostly wind dispersed rather than animal dispersed. Edge effects seem less important there, though this is based on limited data in Asia. African forests are not well studied overall and generally have lower plant diversity. Climates vary among and across all three regions, further complicating things. It’d be great to see more fragmentation work in both Asia and Africa, and for that reason I’ve been very happy to see the SAFE project—which is a large-scale experimental fragmentation study like ours—commencing in Malaysian Borneo. SAFE is being headed by Rob Ewers, a former postdoc of mine, who’s now at Imperial College in the UK.

Mongabay: After 32 years the study site is now under threat. What’s going on?

William Laurance: Really foolish encroachment, mostly being pushed by an intransigent federal agency in Brazil, known as SUFRAMA, that seems to think it’s still the 1970s. SUFRAMA is trying to settle hundreds of families in forests in and around our study area. The soils here are incredibly poor and it’s very difficult to eke out a living in this area, which is also rife with diseases.

Thomas Lovejoy: That SUFRAMA plan is on hold now, so with a new Brazilian administration there may be a chance to move in a good direction.

William Laurance: It’s astounding in this day and age that we’re still fighting to save some of the planet’s most valuable ecosystems from biodiversity and carbon-storage perspectives, in order to stop them being turned into ecological wastelands that support little more than rank human poverty.

CITATION: William F. Laurance, José L.C. Camargo, Regina C.C. Luizão, Susan G. Laurance,

Stuart L. Pimm, Emilio M. Bruna, Philip C. Stouffer, G. Bruce Williamson,

Julieta Benítez-Malvido, Heraldo L. Vasconcelos, Kyle S. Van Houtan, Charles E. Zartman,

Sarah A. Boyle, Raphael K. Didhamm, Ana Andrade, Thomas E. Lovejoy. The fate of Amazonian forest fragments: A 32-year investigation. Biological Conservation. 144 (2011) 56–67.

Related articles

Forest fragment climate not driven by edge-effect

(12/19/2010) Examining ten forest fragments in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, researchers have undercut the theory that the climate of forest fragment’ is driven by the edge-effect. Writing in mongabay.com’s open source journal Tropical Conservation Science, researchers found that edge-effect was too simple to explain the microclimate of isolated forest fragments from 3 to 3,500 hectares large, each at least 80-years-old.

Satellites show fragmented rainforests significantly drier than intact forest

(10/13/2010) A new study in Biological Conservation has shown that edge forests and forest patches are more vulnerable to burning because they are drier than intact forests. Using eight years of satellite imagery over East Amazonia, the researchers found that desiccation (extreme dryness) penetrated anywhere from 1 to 3 kilometers into forests depending on the level of fragmentation.

How to make forest fragments more hospitable to wildlife

(01/27/2009) While deforestation garners more attention from environmentalists, fragmentation of forest habitats is of significant concern to ecologists. As forest is fragmented into islands by logging, roads, agriculture, and other disturbances, edge effects alter the structure, microclimate and species composition of the forest patches, usually reducing the overall number of species. Forest specialists are most likely to suffer, losing out to “weedier” generalists and species that can tolerate forest “edge” conditions. A new study, conducted in the Brazilian Amazon, takes a detailed look at the types of birds that are likely to persist, and even thrive, in forest fragments.

Forest corridors key to maintaining biodiversity in fragmented landscape

(10/07/2008) Alta Floresta, a region in the Brazilian Amazon state of Mato Grosso, has experienced one of the highest deforestation rates on the planet since the mid-1980s due to the influx of colonists and ranchers who converted nearly half the region's forest land to pasture and agricultural plots. The change has had significant ecological impacts, including reducing the availability of water, increasing the incidence of forest fires, fragmenting remaining forest cover, and diminishing the quality of habitat for wildlife.

Island biogeography theory doesn’t explain biodiversity changes in forest fragments

(07/28/2008) Island biogeography theory, the idea that fragmented ecosystems have lower species richness per unit of area compared with contiguous habitats, has served as a useful conceptual model to understand the effects of habitat fragmentation but fails to explain the complexities of change in isolated forest fragments, according to a synthesis published last month in the journal Biological Conservation.

Markets could save forests: An interview with Dr. Tom Lovejoy

(03/20/2008) Market mechanisms are increasingly seen as a way to address environmental problems, including tropical deforestation. In particular, compensation for ecosystem services like carbon sequestration — a concept known by the acronym REDD for “reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation” — may someday make conservation a profitable enterprise in which carbon traders are effectively saving rainforests simply by their pursuit of profit. Protecting rainforests and their resident biodiversity would be an unintentional, but happy byproduct of profit-seeking endeavors.

Fragmentation puts Mexican howlers at risk

(03/03/2008) Forest fragmentation is putting mantled howler monkeys in southern Mexico at risk, reports a new study, published in the inaugural issue of the open access e-journal Tropical conservation Science.

Rainforest fragmentation affects reptiles and amphibians

(02/20/2008) Deforestation of tropical ecosystems is one of the major threats to biological diversity. Anthropogenic activities transform tropical environments into semi-natural landscapes generating a great amount of forest edge that limits with pastures and agricultural lands.

Parasites a key to the decline of red colobus monkeys in forest fragments

(10/25/2007) Forest fragmentation threatens biodiversity, often causing declines or local extinctions in a majority of species while enhancing the prospects of a few. A new study from the University of Illinois shows that parasites can play a pivotal role in the decline of species in fragmented forests. This is the first study to look at how forest fragmentation increases the burden of infectious parasites on animals already stressed by disturbances to their habitat.

Fragmentation killing species in the Amazon rainforest

(11/27/2006) Forest fragmentation is rapidly eroding biodiversity in the Amazon rainforest and could worsen global warming according to research to be published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “Rainforest trees can live for centuries, even millennia, so none of us expected things to change too fast. But in just two decades-a wink of time for a thousand year-old tree-the ecosystem has been seriously degraded.” said Dr. William Laurance, a scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama and leader of the international team of scientists that conducted the research.