The Turkana people of northern Kenya are currently being hard hit by hunger and drought, which some experts say could have links to climate change. Observers have long warned that the world’s poor and marginalized will suffer the most from climate impacts even though they are the least responsible. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

If last year was the first in which climate change impacts became apparent worldwide—unprecedented drought and fires in Russia, megaflood in Pakistan, record drought in the Amazon, deadly floods in South America, plus record highs all over the place—this may be the year in which the American public sees climate change as no longer distant and abstract, but happening at home. With burning across the southwest, record drought in Texas, majors flooding in the Midwest, heatwaves everywhere, its becoming harder and harder to ignore the obvious. Climate change consultant and blogger, Brian Thomas, says these patterns are pushing ‘prominent scientists’ to state ‘more explicitly that the pattern we’re seeing today shows a definite climate change link,’ but that it may not yet change the public perception in the US.

Thomas, who writes frequently about climate adaptation and justice, says that some governments—local and national—are beginning to act on adapting to a new, warmer, and more unpredictable world. However, many are not moving quickly enough.

“A great many coastal towns and cities are acting as if they have centuries to do with sea level rise. Because the impacts feel like they are a long way off, most people are procrastinating. It’s a cognitive problem we face because of the very long-term nature of climate change impacts. The risks are grave, the impacts are here, but the problem doesn’t feel urgent,” he told mongabay.com in an interview.

Brian Thomas. |

Although Thomas says the reality of climate change is hitting certain sectors of society, such as the insurance sector, the ‘well-funded’ climate change industry is continuing to halt progress on both mitigating and adapting to climate change. But the damage may be greatest when it comes to the moral dimension of climate change, especially since those hit the hardest by climate impacts (the poor in developing nations) are the least responsible for the problem.

“The persistent downplaying of the moral dimensions of climate change is one of the most damaging effects of the climate change denial industry,” Thomas says. “The wealthy countries that have prospered from many decades of emissions have a moral obligation to help those who are suffering the consequences in the developing world. The United States, despite its self-perception, is quite stingy with foreign aid, especially if you eliminate the military portion of the aid to Israel, Egypt, and other arrangements. Much more needs to be done to help developing countries.’

On top of direct aid, Thomas says that “technology and know-how swaps are the linchpin. It would be a tremendous boost for the developing world if the West could assist them in skipping some of the steps to development. This goes along with active support for education assistance.”

In a July 2011 interview Brian Thomas discussed how extreme weather may (or may not) be changing the public perception of climate change, how countries are adapting to climate impacts, and why the moral issues of climate change must be addressed.

INTERVIEW WITH BRIAN THOMAS

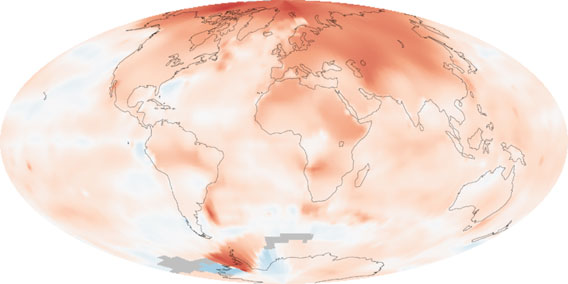

A warmer world: map shows global mean temperatures from 2000-2009 as compared to 1951-1980. Map courtesy of NASA. Click to enlarge.

Mongabay: What is your background?

Brian Thomas: I studied the philosophy of science as an undergraduate, and have kept up my interest since then. After years of working as a writer for Wall Street firms, I went to Swiss Re, where I was heartened to discover that the insurance industry, particularly reinsurers, pay close attention to climate change. From there, my interest in climate issues has grown, and I now work as a sustainability consultant to businesses and governments. I’m not a scientist, but a lay person who makes a steady effort to follow the science, and make use of it in my work as a climate change consultant.

Mongabay: The last 18 months appears unprecedented globally for extreme weather events what is the evidence that such events are linked to a warming planet?

Brian Thomas: Most scientists make a boilerplate statement that you cannot link a single climate event to climate change, but that weather extremes are consistent with the theory of anthropogenic global warming. Nevertheless, over the last year or so I’ve noticed a number of prominent scientists stating more explicitly that the pattern we’re seeing today shows a definite climate change link—we’re seeing large numbers of records being broken routinely in a wide number of places, and in many categories, such as heat, flooding, precipitation, etc.

Mongabay: What is climate adaptation?

Brian Thomas: In my blog, Carbon Based, I use the framework created by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to deal with adaptation, which I interpret as “Everything we do to respond to the impacts of global warming.” The topics include water, agriculture, floods, extreme weather, disasters, forest fires, sea level rise, infectious diseases, ecological stress, computer modeling, land use, resilience, paleoclimatology, developing countries, indigenous people, scientific research, insurance, and finance. I also represent the psychological and sociological aspects of climate instability.

Mongabay: What are some examples of innovative adaptations going on worldwide?

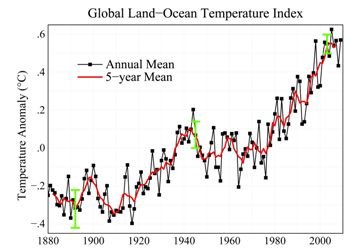

Covering global surface temperatures from 1880-2000, the graph shows global annual surface temperatures relative to 1951-1980 mean temperatures. Except for a leveling off between the 1940s and 1970s, Earth’s surface temperatures have increased since 1880. As shown by the red line, long-term trends are more apparent when temperatures are averaged over a five year period. Image credit: NASA/GISS. |

Brian Thomas: Many adaptation measures are tools that have been around for a long time. Climate impacts often force governments and individuals to undertake these measures sooner and on a greater scale we would under ordinary circumstances.

Coastal cities in wealthy countries, like New York or Rotterdam, are taking a number of measures to make their infrastructures more resilient. It’s an immense effort that includes comprehensive stormwater and drainage strategies, flood planning, and urban transportation planning.

At the same time, developing countries like the Philippines and Vietnam are quite busy on this front, obtaining aid for infrastructure improvements, struggling to improve local land use rules and patterns. Many Philippine local governments have been quite active and busy in coming up with plans and identifying their vulnerabilities.

Around the world, a number disaster risk reduction measures are being implemented, which are aimed at reducing the size of the targets that can be damaged by extreme weather or earthquakes. Much of this involves changing land use rules that people are discouraged from building in risky areas. It’s a simple idea, but it’s rarely done in a consistent way. The effort is important, since a natural disaster can wipe out decades of development work.

Mongabay: In what areas is adaptation desperately needed, but has not happened yet?

Brian Thomas: A great many coastal towns and cities are acting as if they have centuries to do with sea level rise. Because the impacts feel like they are a long way off, most people are procrastinating. It’s a cognitive problem we face because of the very long-term nature of climate change impacts. The risks are grave, the impacts are here, but the problem doesn’t feel urgent.

I also think that flood control in general needs a lot of modernizing. In the US, the Army Corps of Engineers approach to controlling nature keeps on encountering events like the 2011 floods of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, which demonstrate the limits of a hard engineering approach.

Mongabay: Speaking of the US, this summer has seen historic flooding, fires, droughts, and heatwaves in the states. Do you think such events are likely to change the public perception of climate change in the US?

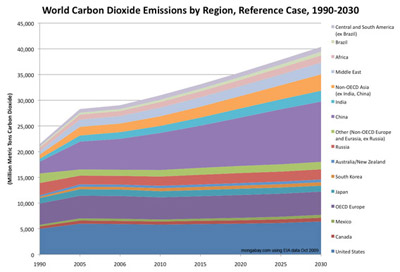

Carbon Dioxide Emissions by Country, 1990-2030. Click image to enlarge. |

Brian Thomas: I wish public perceptions would change, but everyone has a number of cognitive biases that make it hard to pay attention to long-term, slow-moving problems like climate change. What’s more, the denial industry is well-funded and it takes full advantage of these biases. The combination of these two forces means that after the shock of the latest catastrophe wears off, people’s memories recede pretty quickly. If it’s not affecting them directly today, people are inclined to ignore it, or to kick the can down the road to later generations.

Mongabay: This was a historic year for deadly tornados in the US. Is there any evidence that connects climate change and tornados?

Brian Thomas: I gather that for tornados the climate link is more complex and hard to discern for a variety of reasons.

Mongabay: What are your thoughts on the severity of the up-coming hurricane season?

Brian Thomas:If scientists are full of hedged statements and qualifications when predicting hurricane seasons, then it’s only prudent for me, too. But I think we can take a valuable cue from the insurance industry—if the risk of a catastrophically turbulent hurricane is greater than zero, then the rational thing to do is to take precautions.

Mongabay: Scientists say most of the worst climate impacts are expected in countries that are least to blame for historic greenhouse gas emission and are the poorest. Are wealthier nations obligated to aid such nations with adaptations?

Brian Thomas: They have a very strong obligation that so far they are ignoring. The persistent downplaying of the moral dimensions of climate change is one of the most damaging effects of the climate change denial industry. The wealthy countries that have prospered from many decades of emissions have a moral obligation to help those who are suffering the consequences in the developing world. The United States, despite its self-perception, is quite stingy with foreign aid, especially if you eliminate the military portion of the aid to Israel, Egypt, and other arrangements. Much more needs to be done to help developing countries.

Mongabay: What are some of the ways, other than simply direct financial support, in which wealthier nations can aid poorer?

Solar power trough in the US. Photo by: Sandia National Laboratory. |

Brian Thomas: Technology and know-how swaps are the linchpin. It would be a tremendous boost for the developing world if the West could assist them in skipping some of the steps to development. This goes along with active support for education assistance. Wealthy countries show little sign of taking these steps on a large scale, but the world’s needs are large.

Mongabay: Currently East Africa, especially Somalia, is in the grips of one of its worst famines in decades due in part to drought. Is this an example of how climate change is directly impacting human lives?

Brian Thomas: Some people have suggested that East Africa has been drying because of climate change, but here again, causal attribution is tricky. Nobody knows where the trends of rainfall in the region are heading statistically. Most experts I’ve read seem to agree that the drought is a strong La Niña event, but are still uncertain how these events are affected by climate instability.

Mongabay: Is the growing focus on climate adaptation in danger of taking the wind out of the sails of global society tackling the underlying problem, i.e. greenhouse gas emissions?

Brian Thomas: I hope not. A number of people have pointed out that cutting carbon emissions is by far the most economical way of adapting to climate change. Earlier on, many climate denialists and their fellow-travelers like Bjorn Lomborgs promoted adaptation as an alternative to mitigation, which is absurd. In fact, most of those opposed to action on mitigation are going to be aghast when they see the bill for adaptation measures, which will be huge.

Mongabay: What is climate justice?

Brian Thomas: It’s the attempt to address the unfairness of the world’s greenhouse emissions budget, in which a minority of the world’s population are responsible for the carbon emissions that are inflicting major suffering on the majority.

Mongabay: Are there any concrete examples of climate justice to date?

Brian Thomas: I wish I had some to bring to your attention. There are plenty of examples of climate injustice. Many Pacific islands are in danger of inundation, and where they will relocate is a pressing regional issue. Small coastal towns with vulnerable topographies are being eroded in Alaska and elsewhere. And since this is Mongabay, I should mentioned forests around the world, where the crucial role of indigenous residents in caring for forests is often under pressure large-scale economic forces.

Mongabay: Would you characterize climate change as largely a moral issue?

Brian Thomas:I would—I think the ethics of climate change give us a change to unify a great deal of disparate scientific information in a consistent, action-oriented way.

A recent book by Stephen Gardiner does an excellent job of exploring the ways the world’s most affluent nations pass the cost of their emissions on to the poorer and weaker citizens of the world, and to later generations. He also explains how our poor grasp of climate science, international justice, and our very relationship to nature undermines our willingness to take action. It’s called A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change. I recommend it.

Related articles

‘Heatwave’ in Arctic decimating sea ice

(07/21/2011) Arctic sea ice could hit a record low by the end of the summer due to temperatures in the North Pole that are an astounding 11 to 14 degrees Fahrenheit (6 to 8 degrees Celsius) above average in the first half of July, reports the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). Already the sea ice extent is tracking below this time in 2007, which remains the record year for the lowest sea ice extent. The sea ice hits its nadir in September before rebounding during the Arctic winter.

Tens of thousands starving to death in East Africa

(07/20/2011) As the US media is focused like a laser on theatric debt talks and the UK media is agog at the heinous Rupert Murdoch scandal, millions of people are undergoing a starvation crisis in East Africa. The UN has upgraded the disaster—driven by high food prices, conflict, and prolonged drought linked by some to climate change—to famine in parts of Somalia today. Mark Bowden, UN humanitarian coordinator for Somalia, has said that tens of thousands Somalis have died from malnutrition recently, “the majority of whom were children.”

NASA image: hotter lows and hotter highs in the US

(07/13/2011) New images show just how much US temperatures in July and January have changed recently as the nation feels the impact of global climate change. Dubbed the ‘new normals’ of US climate, the maps focus on July maximums – typically the hottest month of the year – and January minimums – typically the coldest month. While both July highs and January lows warmed recently, January lows saw the biggest jump.