Tam, a male Sumatran rhino is kept in semi-captivity in Borneo with hopes to mate him with a female. The Sumatran rhinos on Borneo are actually a unique subspecies, dubbed the Borneo rhino, they are the world’s smallest.Photo by: Jeremy Hance.

Some conservation challenges are more daunting than others. For example, how do you save a species that has been whittled down to just a couple hundred individuals; still faces threats such as deforestation, poaching and trapping; is notoriously difficult to breed in captivity; and is losing precious time because surviving animals are so few and far-apart that simply finding one another—let alone mating and successfully bringing a baby into the world—is unlikely? This is the uphill task that faces conservationists scrambling to save the Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis). A new paper in Oryx, aptly named Now or never: what will it take to save the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis from extinction? analyzes the conservation challenge, while putting forth a number of recommendations.

The number one threat to Sumatran rhinos has changed in recent decades. Poaching for rhino horn used in Chinese traditional medicine—though scientific studies show conclusively the horn has no medicinal value whatsoever—and habitat loss from logging and plantations have taken a back seat to the concern that the Sumatran rhino populations may be too small—and scattered—to walk back from the edge of extinction.

“As numbers of individuals of a species decline to a low very level, the various factors associated with very low numbers (e.g. narrow genetic base, locally skewed sex ratio, difficulty in finding a fertile mate, reproductive pathology associated with long non-reproductive periods) conspire to drive numbers even lower, to the extent that death rate eventually exceeds birth rate, even with adequate habitat and zero poaching,” explains Junaidi Payne with WWF and co-author of the paper. “Poaching will hasten the extinction of the Sumatran rhino, but is no longer the main driver of its extinction.”

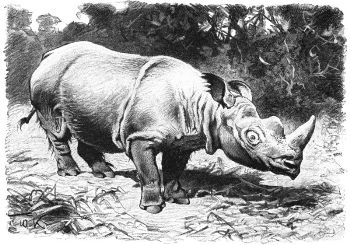

Illustration of the Sumatran rhino, 1927. Notice the hair: the Sumatran rhino is the hairiest of the rhino species and is thought to be related to the extinct woolly rhinoceros. |

Technically, the Sumatran rhino is not the world’s most endangered rhinoceros. That bleak honor actually belongs to the Javan rhino, of which only around 50 survive. However conservation of the Javan rhino is far more straightforward as they all survive in a single park and are known to be breeding. In contrast, the Sumatran rhino is spread out in distinct populations over Sumatra, Borneo, and peninsular Malaysia, complicating the conservationists’ task.

However disheartening, this does not mean the Sumatran rhino is a goner, at least not according to past conservation success stories, such as the white rhino which was resurrected from just 20 individuals and the California condor which is making strides after dropping to only 22. Instead it means that the Sumatran rhino will likely require lots of hands-on conservation help to survive. If left alone—even if no more poaching occurred and no more habitat was lost—the Sumatran rhino could very well still go extinct. Scientists say the species needs extra care.

But what kind of care? Captive breeding of the species in the past was little short of a disaster: 40 rhinos taken from the wild in the 1980s resulted in almost total failure. Only one female rhino successfully bred, producing 3 offspring by 2007. Learning from this, researchers now say a different plan is needed.

“By bringing fertile males and females into a semi-wild captive facility we would increase the likelihood of them mating,” Ahmad Zafir, leader author of the paper, told mongabay.com. “Something that is not easy to happen at the moment where you have solitary animals not being able to find their mate because there is just too few of them. The semi-wild approach would also greatly minimize the risk of poaching.”

Scar from snare that injured Sumatran rhino, Tam. Photo by: Jeremy Hance. |

Semi-wild captivity means exactly that. Instead of capturing rhinos and shipping them half way across the world to say the US or Europe, a few rhinos would be captured and kept in large enclosures in their native rainforest habitat. They would be monitored by a team of experts and protected 24/7, but would also be given more free-reign than if kept in a zoo. A program such as this has already been set up at Way Kambas National Park in Sumatra: five rhinos currently roam a hundred hectares. While there has been no offspring yet, one of the females did become pregnant but miscarried, which is not uncommon. Now, the Malaysian state of Sabah in Borneo is working to set up a second facility for its rhinos. They currently have one rhino, Tam, who was found in a palm oil plantation after being injured by a snare. They are now working to secure others.

According to Payne this plan makes the most sense: “In semi-natural fenced conditions, the close monitoring that can be done potentially allows things to be done that would be impossible in the wild. This might include providing better nutrition or administering hormones to boost reproductive prospects.”

The most viable populations for such efforts are currently surviving in four protected areas, two in Sumatra, including Way Kambas, and two in Sabah.

“We called them priority areas as they have recorded relatively high Sumatran rhino population estimates and track encounter rates,” says Zafir.

A fifth population has historically been recorded in peninsular Malaysia, but its status currently remains unknown.

“I don’t think anyone knows if the species is extinct in Peninsular Malaysia. It is almost impossible to know when the last individual of a species has died, especially for solitary animals in extensive rainforest,” explains Payne. “Clearly, the Sumatran rhino is on the verge of extinction in Peninsular Malaysia because we know that populations have been wiped out, or nearly so from most or all their former strongholds, and that there have been no reports of young rhinos for many years.”

As semi-wild captivity is being tested, the conservationists say that remaining wild rhinos need sustained, and even greater protection. Anti-poaching teams—who also destroy snares and traps—police officials, and intelligence officers, as well as researchers are all required to safeguard the last populations in protected area.

Of course, such plans require funds. Conservationists need support not only from local governments but from private sources as well. Payne says that private funding may in the end make the difference between extinction and survival for the Sumatran rhino.

“The efforts of most governments to prevent the extinction of critically endangered species have always been rather marginal,” says Payne. “Black and white rhinos in Africa were saved from extinction just over a century ago largely by private, rather than governmental efforts. I do not think the situation has changed much. Governments tend to favor conservation efforts for habitats, for specific sites, and for species which are not too seriously endangered.”

The cost to keep conservation programs going for Sumatran rhinos, however, is significantly less than some more high-profile species.

Even in semi-captivity rhinos need help getting a wide-variety of foods. Here, rangers weigh out food for semi-captive Sumatran rhino. Photo by: Jeremy Hance. |

“We estimated that current annual amount spent to sustain the conservation work for the Sumatran rhinos in four priority sites is around $1.2 million. This is actually far less than the amount that was estimated late last year committed for tiger conservation at 42 priority sites, which was estimated to be around $47 million!” says Zafir.

Payne, always a realist, says there is about a 50 percent chance that the Sumatran rhino will beat extinction, and a 50 percent chance it will slowly wink away, the last one vanishing in a forest somewhere, likely far from human eyes.

“We will know within a decade or so,” he says. “If numbers continue to decline, and captive management is not allowed, or fails, then it will be time to allow nature to take its course.”

When asked what the public could do to help save the species, Payne says “[supporting] the Sumatran and Borneo Rhino Sanctuary programs by any means possible, whether financially or otherwise.”

Zafir adds that people should also “[share] their concern on the plight of the species with their government, wildlife authorities and general public. They could also help local and international NGOs which are now actively trying hard to save the species.”

CITATION: Abdul Wahab Ahmad Zafir, Junai di Payne, Azlan Mohamed, Ching Fong

Lau, Dionys i us Shankar Kumar Sharma, Raymond Alfred

Amirtharaj Christy Williams, Senthival Nathan, Widodo S . Ramono and

Gopalasamy Reuben Clements. Now or never: what will it take to save the Sumatran

rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis from

extinction?. Oryx. 45(2), 225–233 doi:10.1017/S0030605310000864.

Related articles

Down to 50, conservationists fight to save Javan Rhino from extinction

(05/17/2011) Earlier this year, the International Rhino Foundation launched Operation Javan Rhino to prevent the extinction of the critically endangered Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), formerly found in rain forests across Southeast Asia. Operation Javan Rhino is a multi-layered project which links field conservation, habitat restoration, and management efforts with the interests of local governments and communities. The following is an interview with Susie Ellis, Executive Director of the International Rhino Foundation.

(05/14/2011) A new animation created using Google Earth offers a tour of an area of forest slated for destruction by logging companies. The animation, created by WWF-Indonesia and David Tryse, with technical assistance from Google Earth Outreach, highlights the rainforest of the Bukit Tigapuluh landscape in Sumatra, the only island in the world that is home to Sumatran tigers, elephants, rhinos, and orangutans. All of these species are considered endangered or critically endangered due to habitat destruction or poaching.

Belief and butchery: how lies and organized crime are pushing rhinos to extinction

(05/11/2011) Few animals face as violent, as well organized, and as determined an enemy as the world’s rhinos. Across the globe rhinos are being slaughtered in record numbers; on average more than one rhino is killed by poachers everyday. After being shot or drugged, criminals take what they came for: they saw off the animal’s horn. Used in Traditional Chinese Medicine, which claims that it has curative properties, rhino horn is worth more than gold and cocaine on the black market. However, science proves all this cash and death is based on a lie. ‘There is no medicinal benefit to consuming rhino horn. It has been extensively analyzed in separate studies, by different institutions, and rhino horn was found to contain no medical properties whatsoever,’ says Rhishja Larson.

Video: camera trap proves world’s rarest rhino is breeding

(02/28/2011) There may only be 40 left in the world, but intimate footage of Javan rhino mothers and calves have been captured by video-camera trap in Ujung Kulon National Park, the last stand of one of the world’s most threatened mammals. Captured by World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Indonesia’s Park Authority, the videos prove the Javan rhinos are, in fact, breeding. “The videos are great news for Javan rhinos,” said Dr. Eric Dinerstein chief scientist at WWF, adding that “there are no Javan rhinos in captivity—if we lose the population in the wild, we’ve lost them all.”

Rhino horn price matches cocaine

(02/13/2011) As a rhino poaching epidemic continues throughout Africa and Asia, the price of rhino horn has matched cocaine, according to the UK’s Daily Mirror. The price of illegal powdered rhino horn—obtained by killing wild rhinos and sawing off their horns—has hit £31,000 per kilo or nearly $50,000 per kilo. The price has already topped that of gold.

Reforestation effort launched in Borneo with nearly-extinct rhinos in mind

(11/18/2010) The Rhino and Forest Fund (RFF) has partnered with the Forestry Department of Sabah in northern Borneo to launch a long-term reforestation project to aid Malaysia’s threatened species with particular emphasis on the Bornean rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni), one of the world’s most imperiled big mammals. The reforestation project will be occurring in and adjacent to Tabin Wildlife Reserve, which is surrounded on all sides by oil palm plantations.

Fighting poachers, going undercover, saving wildlife: all in a day’s work for Arief Rubianto

(09/29/2010) Arief Rubianto, the head of an anti-poaching squad on the Indonesian island of Sumatra best describes his daily life in this way: “like mission impossible”. Don’t believe me? Rubianto has fought with illegal loggers, exchanged gunfire with poachers, survived four days without food in the jungle, and even gone undercover—posing as a buyer of illegal wildlife products—to infiltrate a poaching operation. While many conservationists work from offices—sometimes thousands of miles away from the area they are striving to protect—Rubianto works on the ground (in the jungle, in flood rains, on rock faces, on unpredictable seas, and at all hours of the day), often risking his own life to save the incredibly unique and highly imperiled wildlife of Sumatra.

To save species, Malaysia implements daring plan to trap wild Bornean rhino

(06/13/2010) With less than 40 individuals left in the world, the Bornean rhino is a small step away from extinction. Yet conservationists and government officials in the Malaysian state of Sabah are not letting this subspecies of the Sumatran rhino go without a fight. Implementing a daring last-ditch plan to save the animal, officials are working to capture a wild female to mate with a fertile male named Tam, who was rescued after wandering injured into a palm oil plantation two years ago.

Poachers kill world’s rarest rhino in Vietnam

(05/11/2010) Poachers have killed a Javan rhino in Vietnam for its horn according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). With only an estimated 60 individuals left the Javan rhino is the world’s rarest and classified by the IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered. The rhino was found dead from a gunshot wound and its horn cut off in Cat Tien National Park in Vietnam.

Sumatran rhino loses pregnancy: conservationists saddened but remain resolute

(03/31/2010) Rhino conservationists’ hopes were dampened today by news that Ratu, a female Sumatran rhino, had lost her pregnancy. Just months after the announcement of the pregnancy—the first at Indonesia’s Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary in Way Kambas National Park—Ratu lost the embryo. Still, say conservationists, the very fact that Ratu became pregnant at all should keep hope alive for the beleaguered species.

Face-to-face with what may be the last of the world’s smallest rhino, the Bornean rhinoceros

(12/01/2009) Nothing can really prepare a person for coming face-to-face with what may be the last of a species. I had known for a week that I would be fortunate enough to meet Tam. I’d heard stories of his gentle demeanor, discussed his current situation with experts, and read everything I could find about this surprising individual. But still, walking up to the pen where Tam stood contentedly pulling leaves from the hands of a local ranger, hearing him snort and whistle, watching as he rattled the bars with his blunted horn, I felt like I was walking into a place I wasn’t meant to be. As though I was treading on his, Tam’s space: entering into a cool deep forest where mud wallows and shadows still linger. This was Tam’s world; or at least it should be.