Africa’s forests are fast diminishing to the detriment of climate, biodiversity, and millions of people of dependent on forest resources for their well-being. But is the full conservation of Africa’s forests necessary to mitigate global climate change and ensure environmental stability in Africa? A new report by The Forest Philanthropy Action Network (FPAN), a non-profit that provides research-based advice on funding forest conservation, argues that only the full conservation of African forests will successfully protect carbon stocks in Africa.

Focusing on the role of African forests in helping mitigate climate change, the report, Protecting and restoring forest carbon in tropical Africa: A guide for donors and funders is the first to explore methods to protect and restore Africa’s forests. African forests store more carbon that those of Southeast Asia and are at greater risk than the tropical forests of both Asia and Latin America, according to the report. In fact, forests in Africa are being cleared at a rate nearly three times the world average: the continent lost 3.7 million hectares of tropical forest each year between 2000 and 2005. Because carbon is released when trees are burned or felled, deforestation accounts for 10-15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Protecting and restoring forest carbon in tropical Africa |

“[There seems to be a] belief that Africa’s tropical forests are much less dense than those in Latin America and Asia. The reality is very different – the forests of Sub-Saharan Africa store 171 gigatons of carbon, 35 per cent more than Asia and only a quarter less than Latin America. In part this is because the total forest area is vast – half a billion hectares, out of a total global forest area of four billion hectares. If all of Africa’s tropical forests were to be deforested, that would release around 627Gt of CO2, about 15 years worth of global annual emissions,” explains Bernard Mercer, co-founder of FPAN, in an interview with mongabay.com.

Unlike deforestation in Southeast Asia and South America, the primary difficulty of forest conservation in Africa stems from the people’s desperate need to utilize forest and land resources to survive, acknowledges the report. Over 80 percent of wood harvested from forests in sub-Saharan Africa is used directly for fuel, and small-scale agriculture is a contributing cause in over 80 percent of deforestation cases in Africa.

However, agribusiness and foreign land deals give increasing cause for concern:

“Some participants in these debates argue that you cannot beat economics, so agribusiness expansion is just going to happen, particularly in the savannah areas of the Congo Basin, and in countries like Angola and Tanzania. Our conclusion is that we should all beware of determinism. Donors and funders need to put their weight behind initiatives that seek to achieve a different outcome, in which African agriculture continues to be based on the smallholder model, but with higher yields and improved distribution and food storage systems,” said Mercer.

The report suggests that direct action to help Africans meet their fuel needs would indirectly decrease pressure on Africa’s tropical forests. The FPAN found that supporting domestic timber plantations and distributing efficient stoves may be the most effective methods to decrease reliance on forests for cooking fuel. Their calculations suggest that supplying efficient stoves to Kenya’s rural population (6 million households) could reduce annual fuelwood consumption there by 50 percent, preventing 8.4 million tons of carbon from being released every year.

Child in Gabon. |

Additionally, if domestic timber plantations were to supply all woodfuels, FPAN determined that demand could be met utilizing an area 5-20 percent the size of forest currently harvested, allowing for the preservation of more tropical forest.

“On the critical question of how poor people can afford to pay for plantation outputs, it’s important to be realistic. This is not a problem that can be solved 100 per cent. If it is easy and free of charge to take forest rather than plantation outputs, then it will be tough to achieve a switch. That’s why we suggest the top plantation priority is to meet urban demand in cities like Dar es Salaam, Kinshasa and Nairobi. The citizens of those cities are usually paying for charcoal or woodfuels, rather than going out into forests to collect wood. In many cases woodfuels and charcoal, especially the latter, are being trucked in to cities from forests that are as much as 100 miles away,” Mercer told mongabay.com.

While the FPAN report affirms that Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) is more carbon-friendly than conventional logging, these practices still result in significant carbon loss when compared to strict conservation of intact forests. The report thus advises funding to shore-up existing protected areas, which in tropical Africa are often strapped for resources and unable to provide effective forest protection. Donors could also fund the purchase of forest currently slated for clearing under potential logging concessions, which total around 120 million acres across six Central and West African countries.

The FPAN also advises funding support for forest protection agencies in tropical African countries. Given that a quarter of Africa’s tropical forest is located in the highly unstable and corrupt Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), working to save forest through African governments poses challenges. The most promising policy initiative to encourage governments to conserve forest is the Reducing Emission from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) mechanism, which proposes to compensate tropical nations for not clearing forested land. But negotiations on the implementation of REDD (now REDD-plus) are currently stalled.

Logs in Gabon

AN INTERVIEW WITH BERNARD MERCER

Mongabay: What is your background?

Bernard Mercer |

I’ve spent the last ten years working as an adviser and researcher for philanthropists, donors and other funders. For the first half of this period I was at New Philanthropy Capital, the London-based charity which carries out analysis on the effectiveness of charities, initially as the first CEO, then as the author of Green Philanthropy, a report which provides a broad overview of the environmental landscape, written as guidance for donors and funders.

In the last five years I have concentrated on forests and climate, mostly through FPAN. My passion for forests, climate mitigation and biodiversity came about in an unusual way – from books. In the late 1970s I left Oxford with an English Literature degree and no clear idea of a career path. I ended up in publishing, promoting books on birds and wildlife, and then in 1985 setup my own bookselling business, Natural History Book Service, which miraculously is still serving naturalists, conservationists, scientists and libraries all over the world today. I find it impossible to imagine stopping working in the environmental area, these challenges – particularly climate change – are in my mind and heart the absolutely most pressing problems for our era to tackle.

Mongabay: What motivated you to co-found the Forests Philanthropy Action Network (FPAN)?

When I finished Green Philanthropy I stood back and tried to figure out what I had learned from the research for that report on where the most glaring gaps in provision of guidance for donors and funders were. The forests challenge almost leaped out of the pages. Most of us who work in this area think of the need for forest protection and restoration as on a par with poverty alleviation, health care, education and other major global social problems. Yet, there is very little philanthropic or charitable infrastructure devoted specifically to forests.

Lowland gorilla in Gabon. |

There is no NGO working exclusively on forest conservation, for example. Most of the major NGOs (e.g. Greenpeace, Global Witness, CI, Friends of the Earth, WWF, TNC) do have forest programs, but these sit alongside many other priorities. I think the role of forest conservation within the REDD negotiations has suffered as a result. Most of the specialist forest NGOs are smaller and also tend to focus on the rights and livelihoods of forest peoples (e.g. Rainforest Foundation, Forest Peoples Programme, FERN) rather than on conservation and restoration.

But back to FPAN – this was created by Nick Josefowitz and me to fill a different gap. Nick and I both felt there was a lack of independent analysis focused on identifying the philanthropic interventions which are most successful in combating deforestation and forest degradation in the tropics, particularly those interventions which look at forests from a climate perspective. We felt that this lack of analysis was preventing donors from making informed decisions on how to direct their philanthropy, and consequentially made donors less willing to commit substantial sums to tackling the problem. We set FPAN up in response, with three goals:

- to encourage more charitable trusts, foundations and private individuals to engage with the challenge of protecting and enhancing forests;

- to foster informed debate and dialogue on these issues; and

- to produce research-based guidance for donors and funders who are looking to support effective action on forests.

We’ve held several meetings in London as an initial step toward the first two goals. The Africa report is our first contribution toward the third. Can I just say how grateful I am to Nick and to the other funders who have supported us throughout the marathon process of researching and writing the report – the Packard Foundation, particularly Walt Reid, Tasso and George Leventis, Larry Linden and Roger Ullman of the Linden Trust for Conservation, and Stephen Rumsey of the Wetland Trust.

TROPICAL FORESTS IN AFRICA

Mongabay: What role do Africa’s forests play in the global carbon budget?

I remember talking to a leading tropical forest expert when we were in the early stages of planning the FPAN report and he said ‘but Africa doesn’t have much carbon, does it, surely we just need to concentrate on the Amazon basin and Indonesia?’

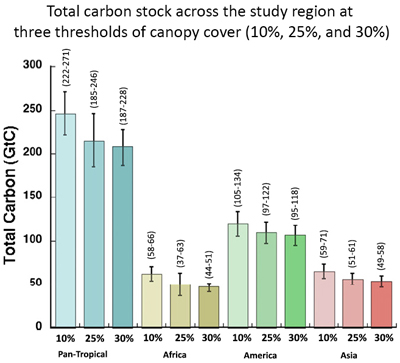

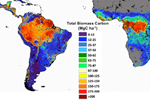

Data from a study published last month in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences came up with lower estimates for Africa’s carbon stocks. |

Since then I’ve found this to be quite a common perspective. It seems to be based on the belief that Africa’s tropical forests are much less dense than those in Latin America and Asia. The reality is very different – Sub-Saharan Africa stores 171 gigatons of carbon dioxide (GtC), 35 per cent more than Asia and only a quarter less than Latin America. In part this is because the total forest area is vast – half a billion hectares, out of a total global forest area of four billion hectares. If all of Africa’s tropical forests were to be deforested, that would release around 627GtC, about 15 years worth of global annual emissions. And the actual current emissions from Africa’s tropical forests are huge: nearly a gigatonne in 2005, about the same as the combined emissions from shipping and aviation in that year.

Mongabay: According to the FPAN report, African forests that store the most carbon also contain the greatest biodiversity—why the connection?

I think the underlying answer to this question is that this is really about big trees. Carbon content per hectare of forest is highest where big trees are still standing – where there hasn’t been selective logging. Big trees hold vast amounts of carbon, perhaps as much as 80 percent of the total in very dense forest. They also act as ecological cornerstones, harboring extraordinary biodiversity, especially insects, but also mammals, birds, parasitical plant species. So big trees=lots of carbon+lots of biodiversity. And it takes hundreds of years for many of them to grow to maturity! That’s why selective logging is a massive folly, a massive mistake.

Mongabay: In Africa, there is a need to balance the immediate and extractive benefits of forests necessary for people’s nutrition and survival with the less tangible and long-term benefits of forest ecosystem services. How can this balance be achieved?

Forest and flooded wetlands in Gabon. |

Answering this question is like walking through a minefield. If we look at the here and now, it seems totally unjustifiable to call for a strategy that would see extraction of non-timber forest products – food and materials – fall right off in tropical Africa during the 21st century. Millions are dependent on these resources, and also, in many cases, have clear rights to them. But the climate and ecosystem services logic is inexorable. If we don’t protect forest carbon we will change the climate in the continent, it will get hotter, water resources will dry up and crops will fail. So there is no question that meeting nutrition needs by investing in more intensive smallholder agriculture outside of forest areas, and sourcing other materials from agroforestry that also is sited outside of forests is the way forward. Many studies show that agricultural intensification is entirely possible, because Africa lags far behind other regions in terms of food output per hectare.

REDD AND CONSERVATION IN AFRICA’s FORESTS

Mongabay: How important is a REDD-plus agreement in efforts to protect and restore Africa’s forest carbon?

In terms of economic stimulus, a REDD dollar will go further in Africa than in other regions, because incomes are so much lower. The work of Plan Vivo is very instructive in this context, because they have demonstrated that very small scale carbon mitigation can significantly improve livelihoods. The downside is that a number of African countries may not qualify for REDD, for a range of reasons, including low current deforestation rates, lack of data/inadequate national emissions reductions strategies, and political issues such as transparency and good governance. We must do everything possible to ensure that all of the nations in tropical Africa are brought into the REDD fold. One glaring gap in the REDD framework which particularly afflicts Africa is the absence of quantification of forest degradation, which is probably the cause of more forest carbon loss than deforestation in the continent, although we don’t have the data to prove that conclusively. Baselines should include degradation, not just deforestation.

Mongabay: A current controversy within the REDD-plus negotiations is the relative weight to give the sustainable management of forests, which includes logging and other extraction, compared with conservation. Why is full protection for forests crucial?

This is a tough question to answer in short form. For the detailed analysis, see the forests chapter of the FPAN report, which examines the range of claims and counter-claims on the merits and demerits of SFM and its derivatives.

So, the short form. The three central pillars of REDD plus – sustainable management of forests, conservation, and enhancement of carbon stocks – imply four core interventions that in theory are going to earn REDD credits: selective logging, (Improved Forest Management – IFM); avoided deforestation (conservation); avoided degradation; and restoration.

Logging in Gabon. |

But at the moment, we only have mechanisms to produce credits for the first two. Effectively, lip service is paid to degradation and restoration, with no substantive progress thus far on the realization of these massive opportunities to reduce emissions and sequester greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

The result is that the whole REDD-plus apparatus is heavily weighted in favor of sustainable management of forests, which many people still do not realize is largely a synonym for selective logging. All these terms – SFM, RIL, IFM, etc – all pretty much mean the same thing – selective logging. And the average carbon loss per hectare from sustainable management approaches looks like around 50 per cent. So that’s why we need full conservation.

If we look back to Montreal in 2005, when Kevin Conrad stood up in the UN meeting and so eloquently launched the REDD era, was this the result that he and others sought? A mechanism to carry on logging, with a bit of forest conservation thrown in?

We need to call time on this thinking. The driving force of REDD-plus should be a tripartite focus on avoiding deforestation, reducing degradation, and restoration. If we could get all three in a dominant position, then REDD-plus would really stand a chance of catalyzing the kind of global forest management that we need for the 21st century.

Mongabay: Ninety percent of Africa’s land is state owned, and only eight percent of Africa’s tropical forests are protected. How can African governments be encouraged to protect and restore forests?

As we make clear in the report, responsibility for the first step toward protection and restoration of Africa’s tropical forests rests with the developed world, particularly the US and the EU. Given the economic context, African governments simply cannot afford to do large scale conservation and restoration within their current budgetary constraints. How can money be channeled into forests when education, health care and economic infrastructure are so clearly the top priorities? The best news for African governments would be a climate bill in the US that allows the federal government and business to offset emissions by purchasing forest carbon credits, and the admission of forest carbon credits into the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS). A number of philanthropists and foundations are funding the work of various NGOs and other organizations to lobby for these goals, and that is certainly a very important priority for funders. The support that the New York-based Linden Trust for Conservation has provided to the Coalition of Rainforest Nations is an inspiring example.

Mongabay: Nations including China, India, and water-scarce Middle Eastern countries have recently begun to broker land deals with African nations for agricultural purposes. How might this trend affect forest protection and environmental standards in Africa? Will REED-plus incentives be available to foreign governments and private firms that will own an increasing share of land in Africa?

In the Agriculture chapter of the FPAN report we look in some detail at what is going on in terms of land deals, and the debates around how much marginal land is available outside of forests for cultivation. The view we came to is that land deals could bring great dangers for forests and forest carbon. We could see significant conversion of forests as a potential consequence, especially if smallholders are displaced and move into marginal areas on forest frontiers to carry on farming. This threat is mostly overlooked, because the debates largely focus on issues of land rights and food security. A good example is Angola, where agribusinesses are seeking to negotiate huge land deals for food crops and biofuels. Angola has the second highest forest area in tropical Africa, but this is rarely mentioned as a factor. There is also a big issue around civil society capacity to raise the visibility of the threat. We couldn’t identify a single Angola-based NGO working on the forests-agriculture relationship.

On the second question, which I guess is more oriented toward REDD land deals, REDD must be a mechanism that creates financial benefits for Africa’s nations and their citizens from forest protection and restoration. It should be a route to prosperity. On the other hand, REDD requires inward investment, and that will only happen if the private sector can develop profitable REDD projects. This is no different from any other inward investment – we know that companies will only build hydro-power installations if these can generate profits, for example. So whilst we should be alert to the risks of REDD becoming a modern form of colonialist exploitation, with foreign interests doing land grabs over the wishes and rights of citizens, we should also focus on the benefits that REDD can bring – employment, tax revenues, income for forest communities from carbon credits and payments for ecosystem services, healthy forests, safer climate. That leaves the role of foreign governments (and particularly their sovereign wealth funds) unanswered. I don’t feel qualified to comment!

Mongabay: Which countries have shown the most progress in forest protection and support of REDD-plus?

The main focus of the FPAN report is the attempt to understand the effectiveness of interventions that aim to protect or restore Africa’s tropical forest carbon, rather than a country by country analysis of REDD-readiness, or national forest protection activity. So our understanding of national performance is somewhat limited. What we did learn from the research and country visits is that there are many people in African governments who have a strong desire to protect their forests. They are engaging with REDD, developing strategies, and working with bodies like UN-REDD and FCPF. My view is that the constraints are within the REDD framework itself, especially the lack of clarity and focus on effective interventions, rather than governmental resistance.

REFORESTATION AND IMPROVING FOREST STEWARDSHIP

Mongabay: How can existing forest preserves be improved, and can any serve as a successful model for the expansion and stewardship of protected areas?

One of the frustrations in doing research for the FPAN report is that it unearthed so many questions that we were unable to answer within our terms of reference. The financing of protected areas is one of the major topics in this category. From the limited data we could identify, it looks like most of the existing forest preserves suffer from absolutely appalling levels of funding, really virtually zero budgets in any meaningful sense, with chronic under-staffing. A comprehensive analysis of protected area finance and headcount would be one of the most valuable research projects that could be carried out. I am sure this would reveal a shocking picture, relative to the budgets and headcount in forested protected areas in the US and the EU. I think the finance shortfall is so bad that anyone would be hard pressed to identify a single existing forested protected area in tropical Africa that is adequately funded, so it is misplaced really to try to identify a successful model when the investment is just not there.

That’s why one of the main recommendations of the report is for funders to help bridge the budget deficits. We know from Terrestrial Carbon Group research, and work by the WCMC in Cambridge, UK, that there is a strong correlation between high forest carbon intensity per hectare and forest preserves in tropical Africa. Some might see this as grounds for complacency – if the correlation is strong, why is there a need for finance? But if the capacity to protect is poor, then the ongoing storage of that forest carbon is going to be at risk.

Mongabay: Small-scale agriculture is a crucial economic activity for many people in

Africa and a leading cause of deforestation. What can donors do to encourage agroforestry and other carbon-friendly agricultural systems?

Because the FPAN report is focused on forest carbon, the research we carried out looks at the impacts on forests of agroforestry and carbon-friendly agricultural systems, and doesn’t seek to do a detailed analysis of the carbon pluses and minuses of these interventions in terms of producing food and materials.

So understanding the best ways of doing carbon-friendly agriculture is another whole topic, for which there is little current analysis. Perhaps the most worrying thing we found is that most agriculture strategists and organizations seem to be ignoring carbon. It is great that agriculture in Africa is now a priority within development agendas, after years of neglect. But if you look at the strategy documents – governmental, UN-driven, private sector, NGO – they concentrate on the issues around output per hectare, smallholders versus corporations, fertilizers versus organics, GMOs, land ownership, food distribution challenges – all absolutely legitimate and critical issues. Terrestrial carbon is just as legitimate and critical, yet seems to have been overlooked. That’s why we recommend donors and funders to support efforts that seek to get carbon on the table in the policy context.

Mongabay: The primary use of wood in Africa is for fuel, and the FPAN report finds that timber plantations could ease pressure on forests. Will poor people be able to pay for timber produced by private plantations when forests serve as an open-access resource?

We recommend two types of plantations that can meet domestic demand: plantations for woodfuels and/or charcoal; and timber plantations for timber and other wood-based materials. Of course, multi-purpose plantations could produce both these outputs from the same site.

On the critical question of how poor people can afford to pay for plantation outputs, it’s important to be realistic. This is not a problem that can be solved 100 per cent. If it is easy and free of charge to take forest rather than plantation outputs, then it will be tough to achieve a switch. That’s why we suggest the top plantation priority is to meet urban demand in cities like Dar es Salaam, Kinshasa and Nairobi. The citizens of those cities are usually paying for charcoal or woodfuels, rather than going out into forests to collect wood. In many cases woodfuels and charcoal, especially the latter, are being trucked in to cities from forests that are as much as 100 miles away.

These distribution systems give governments some leverage. Regulation can be developed that validates the source, and that could then lead to subsidies which incentivize buyers to purchase outputs from plantations rather than forests. This is not easy, but it is possible. In an analogous context, some success has been achieved by Acumen Fund and others to achieve large-scale distribution of malarial bednets in east Africa. Acumen found that the key was investment in distributors, rather than handing out free bednets. Donors and funders could help with subsidies, but also with investment in the distribution systems for woodfuels and charcoal.

Mongabay: In Brazil and Indonesia, an agribusiness model of producing cash-crops for export (such as soy, rubber, and palm) has encouraged forest clearing for monocropped plantations that expand with higher world prices. Is this agricultural model spreading in Africa, and what are its environmental affects?

The report found that agribusiness expansion in tropical Africa is likely to be a near-future event, rather than occurring on large-scales right now. Having said that, since we concluded our research in 2010 there seems to be increasing evidence of activity, for example the Oakland Institute report on hedge funds and land acquisitions that came out recently.

Some participants in these debates argue that you cannot beat economics, so agribusiness expansion is just going to happen, particularly in the savannah areas of the Congo Basin, and in countries like Angola and Tanzania. Our conclusion is that we should all beware of determinism. That future is not pre-ordained. Donors and funders need to put their weight behind initiatives that seek to achieve a different outcome, in which African agriculture continues to be based on the smallholder model, but with higher yields and improved distribution and food storage systems. Above all, we need more clarity around the definition of appropriate land use, so that the carbon losses implied by potential conversion are understood and factored in to decision-making – by governments, agribusinesses, and investors.

Mongabay: Africa’s population growth rate is the highest is the world. How will rising populations impact forest conservation efforts? Development indicators that speed the demographic transition are very low in Africa; should conservationists also prioritize development as it will decrease population growth rates?

In the agriculture chapter we look at the issue of poverty versus wealth as drivers of deforestation, and found that both can act as agents of forest destruction. They are not mutually exclusive. In Indonesia, rising living standards in cities have stimulated a change in diet which sees palm oil used more frequently in cooking. Cultural factors also come into play. In some cities in Africa, charcoal is the preferred energy source, even amongst those who can afford or have access to electricity or LPG.

So while a thought process which encourages conservationists to engage with development in order to bring down population growth is alluring on the surface, it may simply be another means by which we dodge the land-use bullet. My view is that defining the appropriate land-use for a given area is the essential step, and that it is a mistake to assume this can be decided indirectly by addressing problems from the demand side, including the increases in demand triggered by rising populations.

In the EU and the US the regulatory regimes governing land use are increasingly creating a land zoning approach. For example, EU and US citizens are normally not allowed to legally cut down trees in protected areas. House building, the designation of land for industrial use, and conversion of agricultural land for other purposes all require regulatory approval. The land planning system is thus an emerging attempt to rationally decide where various activities can take place, including protecting forests, natural habitats and the agricultural base. In that sense, land-use in the developed world is not driven solely by market forces, or by land rights. It seems logical to me that similar regimes will need to be created everywhere on the planet if we are to meet the needs of 7-9 billion people without sacrificing the natural systems on which we depend. The need for forest carbon stores is one aspect of the wider land zoning debate.

Mongabay: What affect will urbanization have on forest conservation efforts?

This is the kind of topic on which it is dangerous to make blanket statements. If cities do not bring prosperity to their inhabitants, outward migration into forested areas can happen, as has occurred in parts of Brazil and eastern Africa, so any assumption that urbanization is a de facto good for forests is probably too simplistic.

Mongabay: Thus far, African forests have avoided the large-scale and consistent deforestation plaguing Brazil and Indonesia. What factors would spur an increase in African deforestation, and how can they be avoided?

Actually, there has been a lot of deforestation and forest degradation across tropical Africa, it is just not so well known as Brazil and Indonesia. Ghana and Nigeria have both lost 95 per cent of their forests, mostly in the last 50 years, for example. Pressure on forests in Liberia, Kenya and Uganda is acute, and in parts of Cameroon, Sudan, Ethiopia, and in many other countries. To get a sense of the range of threats, look at the excellent UNEP “Atlas of Africa’s Environment,” this provides incredibly valuable visual and textual country by country analysis, detailing how vulnerable forests are to a diverse array of deforestation and degradation drivers.

The FPAN report concludes that there is a set of threats, of which the potential conversion of large forested areas for agriculture and biofuels is one, alongside the huge demand for charcoal and woodfuels, continuing or expanding extensive (or slash and burn or ‘swidden’) agriculture, the potential activation of the many dormant logging concessions, and the extent to which protected areas are genuinely protected.

Averting these threats requires recognition that they are all critical issues. The danger is that strategies may polarize around one issue, leading to neglect of others.

Mongabay: Why is it important for donors to prioritize the purchase of forestry concessions in Africa?

The analysis we carried out on forestry concessions was very interesting. The headline is that logging is not a very profitable activity, when compared to mining, and oil and gas. In countries like Gabon, Angola and the DRC, the actual or potential tax revenues and other economic benefits from mining and oil and gas far outstrip the gains from forestry. The implication is that if a government has the option of granting a license for metals or fossil fuel extraction, or allocating that area for forest protection, it would find it very difficult to justify the forest protection choice in economic terms.

But when the option is between granting a logging concession and granting a forest conservation and restoration concession, the numbers look very different. Our analysis concludes that forest protection is viable if carbon can be sold at c.$3-7 a tonne. The caveat is that forestry is a major source of employment in many African countries, and our analysis was based solely on comparison of likely tax revenues. That caveat is not necessarily as daunting as it may seem. Effective protection and restoration would also require a substantial workforce. So the conclusion we came to is that private sector companies and NGOs could find huge opportunities to achieve forest protection in tropical Africa by focusing on the many dormant logging concessions, especially in the Congo Basin. Of course, this would not be easy. Perhaps the biggest challenge is the cultural shift needed to see standing forests as national assets, rather than as sources of revenue from utilization. And REDD also needs to function properly, with a liquid market in forest carbon credits in the EU and the US as an essential condition.

Mongabay: According to the FPAN report, the current state of knowledge on how to mitigate deforestation and forest degradation is limited. What research is most pressingly needed?

Protecting and restoring forest carbon in tropical Africa |

In terms of primary data, we desperately need to have a more comprehensive grip on the condition of Africa’s tropical forests, on an ongoing basis. It is not enough to assemble snapshots of the baseline now; we need a stream of information over the longer term that charts changes and trends. The best way to do this is to help build the capacity of African research institutes, as Brazil has done with its IMAZON facility.

For secondary data, the needs are different. The ProForest report shows that there is a poor body of comparative analysis, especially on the impacts of different interventions, like Sustainable Forest Management, community forestry and agroforestry. The dearth of analysis of this type makes it all too easy for NGOs, governments, companies and donor agencies to promote particular extractive activities in forests as ‘sustainable’, when they may not be.

Related articles

New global carbon map for 2.5 billion ha of forests

(05/31/2011) Tropical forests across Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia stored 247 gigatons of carbon — more than 30 years’ worth of current emissions from fossil fuels use — in the early 2000s, according to a comprehensive assessment of the world’s carbon stocks. The research, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by an international team of scientists, used data from 4,079 plot sites around the world and satellite-based measurements to estimate that forests store 193 billion tons of carbon in their vegetation and 54 billion tons in their roots structure. The study has produced a carbon map for 2.5 billion ha (6.2 billion acres) of forests.

(12/07/2009) Two of the world’s most serious issues—poverty and climate change—are interconnected. With a rise in one’s income there usually comes a rise in one’s carbon footprint, thereby threatening the environment. Wealthy nations have the highest per capita carbon footprints, while developing nations like India and China—which are experiencing unprecedented economic growth—are becoming massive contributors of greenhouse gases. However, it is those who have the smallest carbon footprint—the world’s poor—who currently suffer most from climate change. Food crises, water shortages, extreme weather, and rising sea levels have all hit the poor the hardest.

Africa calls for “full-range” of bio-carbon as climate solution

(12/10/2008) A coalition of 26 African countries is calling for the inclusion of carbon credits generated through afforestation, reforestation, agroforestry, reduced soil tillage, and sustainable agricultural practices in future climate agreements.