- Earlier this year, the International Rhino Foundation launched Operation Javan Rhino to prevent the extinction of the critically endangered Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), formerly found in rain forests across Southeast Asia.

- Operation Javan Rhino is a multi-layered project which links field conservation, habitat restoration, and management efforts with the interests of local governments and communities.

- The following is an interview with Susie Ellis, Executive Director of the International Rhino Foundation.

Javan rhino mother and calf photographed by a camera trap at Ujung Kulon. Photo courtesy of the World Wildlife Fund. |

Earlier this year, the International Rhino Foundation launched “Operation Javan Rhino” to prevent the extinction of the critically endangered Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), formerly found in rain forests across Southeast Asia.

Operation Javan Rhino is a multi-layered project which links field conservation, habitat restoration, and management efforts with the interests of local governments and communities.

The following is an interview with Susie Ellis, Executive Director of the International Rhino Foundation.

AN INTERVIEW WITH SUSIE ELLIS

Mongabay: Please tell our readers about Operation Javan Rhino and the goals of this project.

.240.jpg) The Critically Endangered Javan Rhino, now found only in Ujung Kulon National Park of Indonesia. Photo courtesy of: International Rhino Foundation. |

Susie Ellis: “Operation Javan Rhino” is a project to further conserve the Javan Rhino, which is considered among the most endangered large animal species on the planet. The species now exists only in one area, the Ujung Kulon National Park of Indonesia.

There was a smaller population of Javan Rhinos “rediscovered” in South Vietnam in the early 1990s, but we believe that this population has recently gone extinct due to widespread local poaching. Now there is a population of no more then 50 rhinos in one location, Ujung Kulon National Park in West Java. The rhinos currently only use two-thirds of the park, and Operation Javan Rhino’s goal is to expand the rhino’s “usable habitat,” in the hopes that they will move into the expanded, restored areas, leading to an increase in numbers.

Mongabay: Is there other habitat available beyond Ujung Kulon that might be suitable for a second, relocated population of Javan Rhinos?

Susie Ellis: We held extensive habitat assessments and looked at

multiple locations across Java to see if there were other workable sites where we might establish a second population in the short-term. Currently there really isn’t anyplace else on Java that is suitable; locations lacked either appropriate food stuff for the rhinos and/or appropriate altitude. The Javan Rhinoceros is a low-altitude species and most of the remaining forests in Java are in the mountains of that island and not ideal for this species. Our long-term goal, though, is to use the expanded and managed habitat at Ujung Kulon to further study the Javan Rhino, encouraging reproduction, and as a staging area to establish additional populations in Indonesia.

Mongabay: It’s a prevailing thought in conservation circles that

habitat restriction is what has limited Javan Rhino numbers at Ujung

Kulon; what are your thoughts in this matter?

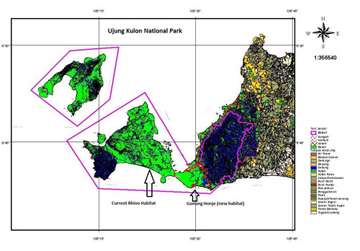

Expanding the habitat of the Javan rhino: area outlined in right-hand section of this map. Map courtesy of International Rhino Foundation. Click image to enlarge. |

Susie Ellis: Right now we have reason to believe that without

additional changes to park management, the park is at carrying

capacity for the rhinos. By expanding the usable habitat, through

replanting rhino food items, creating additional water sources, and

decreasing human encroachment, we are hoping that the carrying

capacity for the park will increase.

This effort will only augment the rhino population incrementally,

and our long-term goal is to establish a second population at a yet to be determined site, probably on the neighboring island of Sumatra.

A large part of the current effort also focuses on getting rid of

an invasive, non-native palm species, the arenga palm, which growing unchecked, is displacing rhino food sources at Ujung Kulon.

Mongabay: Tell us about the invasive palm species; was it introduced by man and is it a symptom of degraded habitat?

An un-welcome addition to the local flora: the arenga palm (Arenga obtusifolia). Photo courtesy of: International Rhino Foundation. |

Susie Ellis: No one is in agreement about how this palm came to Ujung Kulon. We do agree that, unchecked, this palm species is a direct threat to the rhinos, as it is an aggressive species which displaces the native rhino food items. We have been experimenting with different ways of getting rid of this palm from herbicides to physically digging up this palm when found. The latter method (manually digging up the palms) is proving most effective and the least damaging to the area.

Mongabay: Can this be done large scale and cost effectively? It seems like digging up widespread invasive plants requires a lot of work?

Susie Ellis: This is where our close working relationships with the

local communities bordering the park has come into play. Our plan is to work with the local villagers and employ them in the campaign to clear the new habitat of this palm. This employment, of course, enhances their lives and creates direct local benefit from the rhinos.

Mongabay: Is there outreach with the local communities about this

rhino?

Susie Ellis: There is a great deal of regional pride in regard to the

fact that this is the only place on earth where the Javan Rhino exists. We have had to work closely with the local government and communities to foster this understanding. This has been a little bit difficult at times because there was so much encroachment on the park. The government has actually moved 50 families to make way for more adequate management strategies. By creating direct, local benefits from the rhino through habitat management employment, eco-tourism revenues, and educational outreach, the local people are now valuing the Javan rhinoceros as a local resource.

Mongabay: It sounds like the local communities and governments have stepped up. Has the National Government of Indonesia supported this project?

.360.jpg) Indonesian government officials launch new study area (fenced habitat). Photo courtesy of: International Rhino Foundation. |

Susie Ellis: The National Government of Indonesia formally launched the expanded study, habitat restoration, and conservation project for the Javan rhinoceros last year. We now have the support of the provincial government as well as several district governments that are involved. We have worked hard to have government support at all levels. Now valued as a local resource, the various government branches are seeing “constituent benefits” from the Javan rhinos.

Mongabay: Are there any thoughts to further manage the Javan Rhino by developing a captive population?

Susie Ellis: There are no Javan rhinos in captivity currently, and there are no plans to develop a captive population. That may be something we change to offer further insurance for this species. And, though we now know how to keep Sumatran rhinos in captivity, which have similar requirements and diets, this was developed by a trial and error process that was initially very costly, in terms of captive rhinos. There are too few Javan rhinos left to work with in the process of “building a captive population management learning curve.” Conserving the Javan rhinoceros in the wild is a much more practical approach.

Mongabay: Do you think there is a viable population at Ujung Kulon? Is there real hope for this species?

Beneficiaries of a Volcano? In 1883, the nearby volcanic island, Krakatoa, violently erupted, clearing most of human settlements in the area of Ujung Kulon. This event inadvertently created the last sanctuary of the Javan Rhino. Photo courtesy of: International Rhino Foundation. |

Susie Ellis: We think so. Every year we conduct annual surveys of the area and last year we found footprints from at least four juvenile rhinos. We have multiple video footage from camera traps of moms and calves, so we know that the population at Ujung Kulon is actively reproducing.

Mongabay: There are many people who would argue that it’s a lot of effort for one species. Why save the Javan Rhino?

Susie Ellis: My personal thoughts are that I would not want to look into the eyes of my children or my grandchildren and say “we could have saved the Javan rhino, if we had just tried a little harder.”

People of this generation are now realizing that we are indeed the “stewards of this planet,” and we have a responsibility to preserve the planet’s biodiversity for the next generations. The Javan rhinoceros represents a flagship species and symbolizes a whole swath of lost lowland rainforest habitat in Indonesia. Healthier local environments mean better lives for people.

In the process of saving species like the Javan rhino, we are really bringing our own human world into order, to the benefit of all.

ASIA PULP & PAPER’S JAVAN RHINO ANNOUNCEMENT As this interview went to press, Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), a paper products brand now headquartered in of China but with operations in Sumatra and other places, announced a $300,000 contribution over five yeas to Javan rhino conservation efforts. Mongabay.com asked Susie Ellis about APP’s pledge. Mongabay: Asia Pulp & Paper, a controversial logging firm with a somewhat notorious record of greenwashing, recently announced it is supporting Javan Rhino conservation. What are your thoughts on this initiative? Do any Javan rhino conservation groups work with APP at present? Susie Ellis: The Javan rhino exists in Indonesia because of the commitment of the central government to conserving the species, and also because of long-term financial support from the International Rhino Foundation, WWF, and the Asian Rhino Project. These three NGOs have contributed nearly US$10 million to operate on-the-ground rhino protection in Java and southern Sumatra since 1999. With the Ujung Kulon National Park authority, these groups, along with a local NGO, Yayasan Badak Indonesia, have developed and are implementing the Javan rhino project in question. The project is well underway and the majority of funds are in place. A relatively small donation (especially in comparison to their billions of dollars in annual revenue) from APP to the Indonesian government does not mean that they play a role in the on-the-ground conservation of this species. From the NGO perspective, this contribution appears to be truly an attempt to greenwash the company’s image. Many of the major wildlife conservation NGOs, both in Indonesia and internationally, have publicly come out against APP and their methods, with well-documented claims of illegal logging and habitat destruction as well as legally questionable road construction through important wildlife habitat. There also have been accusations of human rights violations by indigenous communities. APP has broken signed agreements with several major international environmental organizations, including the Forest Stewardship Council and the Rainforest Alliance. Many major international companies, including WalMart, Office Depot, Staples, Tiffany & Co., Hugo Boss, and H&M, have stopped buying APP paper products due to their negative environmental practices. I think this speaks volumes. And as they are making the donation we are discussing, Asia Pulp & Paper and their parent company, Sinar Mas Group, have permits pending to clear a significant part of central Sumatra’s Bukit Tigapuluh forest landscape, an ecosystem that provides vital habitat for more than 30 Sumatran tigers, 150 Sumatran elephants, and 130 orangutans, which have recently been reintroduced. The area is also home to two indigenous tribes. |