Brazil’s forest code may be about to get an overhaul.

The federal code, which presently requires landowners in the Amazon to keep 80 percent of their land forest (20-35% in the cerrado), is widely flouted, but has been used in recent years as a lever by the government to go after deforesters. For example, the forest code served as the basis for the “blacklists” which restricted funds for municipalities where deforestation has been particularly high. To get off the blacklist, and thereby regain access to finance and markets, a municipality must demonstrate its landowners are in compliance with environmental laws.

The blacklist approach proved highly effective in attacking the largest driver of deforestation in the Amazon: cattle ranching, which is now facing much stronger regulation than in the past. Several major meat processors now have huge fines hanging over their heads.

But some interests in the agricultural sector are now fighting back. They aim to change the forest code that underpins the blacklists, making it legal to clear larger areas of forest. But the proposed changes include some compromises including a regularization process that would require landowners to register their properties so laws could be more effectively enforced. So while the legal forest reserve requirement may fall, it would be more difficult for ranchers and farmers to disregard the law.

The debate over the forest code is still very much in flux so mongabay.com turned to Daniel Nepstad, a renowned Amazon scientist who runs the North American branch of the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), for an update and analysis on the latest developments and what it means for Earth’s largest rainforest.

Commentary from Dan Nepstad of IPAM

The Forest Code discussion underway in Brazil is complex, and some key issues have not been discussed adequately. Among these is the substantial contribution of the government to the visceral frustration with the Code on the part of landholders, and that has fostered non-compliance. Unfortunately, that deeper debate may be truncated.

Tuesday, the chamber voted to put the Forest Code vote on fast track. That vote is expected next week. Then there would be a Senate vote, then President Dilma would have a chance to veto. She promised to not allow all illegal deforesters off the hook, as the proposed change would do.

There have been important compromise proposals discussed between environmental groups and leaders of agroindustry that would eliminate some of the problematic aspects of the Aldo Rebello proposal. But the revised proposal put forward by Rebello last week didn’t reflect those compromises. It is important to remember that there are some positive changes in Rebello’s proposal, such as the inclusion of the permanent preservation areas (riparian zones, steep slopes) as part of the legal reserve. Rebello also proposed a two-year moratorium on deforestation. But the proposal would gut the permanent preservation concept more generally, shrinking the width of the riparian zone buffer and allowing agricultural activities.

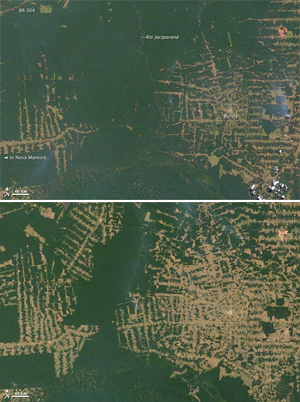

Top image shows deforestation in Brazil’s western state of Rondônia in 2000. Bottom image shows deforestation as of 2010. Images courtesy of NASA |

This is not a black-and-white show-down between environmentalists and farmers. Farmers who I have talked with who have done the (nearly) impossible, and complied with the Forest Code, oppose Rebello’s proposal. They are outraged that their neighbors, who thumbed their noses at the law and converted their cerrado or forest reserves to crops or pasture [before July 2008], would be pardoned. In essence, the proposed changes would send a massive policy signal that those who broke the law get to keep their years of profits from farming and livestock in areas that should have been kept as reserve; those who did the right thing are penalized.

It is a very difficult situation because the real culprit is, in many ways, the government. Enforcement of the law has been lax in many regions, encouraging impunity. In places like Mato Grosso, in the southeastern Amazon, the regulations have changed back and forth in the forest biome, and the forest code has become a source of tremendous frustration and bitterness among farmers and ranchers. In 1995, the law said that you must keep 50% of your farm or ranch in forest. In 1996, this was bumped up to 80% for the entire Amazon forest biome. Then Mato Grosso reduced the requirement back to 50% for the “transition” forest (which is very hard to define). A few years ago, the federal government over-ruled Mato Grosso’s change, and put the requirement back up to 80%. Far a large property holder, every one of these policy flip-flops was the equivalent of changing the property value by several million dollars. Annual profits for a hectare of soy in Mato Grosso today are hovering around $500 or more. The forest, in contrast, provides little or no income. Most state governments never put in place a system by which landholders who are trying to comply with the Forest Code but don’t have enough forest on their land to meet requirements can “compensate” for this forest deficit by paying into funds that maintain or create forest reserves elsewhere.

But the farm lobby is dead set on ramming Rebello’s proposal through to a vote without the necessary analysis and discussion. That analysis must look at the Forest Code as a policy instrument. But it also must look at the government’s capacity to implement the law fairly and facilitate compliance, with a minimum of corruption. This analysis must engage the thousands of farmers and ranchers who are not represented by the extremist “bancada ruralista” farm lobby. These are producers who are outstanding land stewards, ready to follow the law. It is impossible to follow the law, however, when there is an annual threat of changing rules that determine how much of your property can be cultivated or grazed.

Related articles

World’s largest beef company signs Amazon rainforest pact

(04/29/2011) The world’s largest meat processor has agreed to stop buying beef from ranches associated with slave labor and illegal deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, according to the public prosecutor’s office in the state of Acre. The deal absolves JBS-Friboi from 2 billion reals ($1.3 billion) in potential fines and paves the way for the firm to continue selling meat to companies concerned about their environmental reputation.

Brazilian authorities levy $1.2B in fines against beef traders linked to deforestation, slave labor

(04/15/2011) Brazilian authorities are seeking 2 billion reals ($1.2 billion) in fines against 14 companies accused of buying beef sourced from ranches that have illegally cleared Amazon rainforest or exploited workers in the state of Acre, reports AFP.

Concerns over deforestation may drive new approach to cattle ranching in the Amazon

(09/08/2009) While you’re browsing the mall for running shoes, the Amazon rainforest is probably the farthest thing from your mind. Perhaps it shouldn’t be. The globalization of commodity supply chains has created links between consumer products and distant ecosystems like the Amazon. Shoes sold in downtown Manhattan may have been assembled in Vietnam using leather supplied from a Brazilian processor that subcontracted to a rancher in the Amazon. But while demand for these products is currently driving environmental degradation, this connection may also hold the key to slowing the destruction of Earth’s largest rainforest.

Future threats to the Amazon rainforest

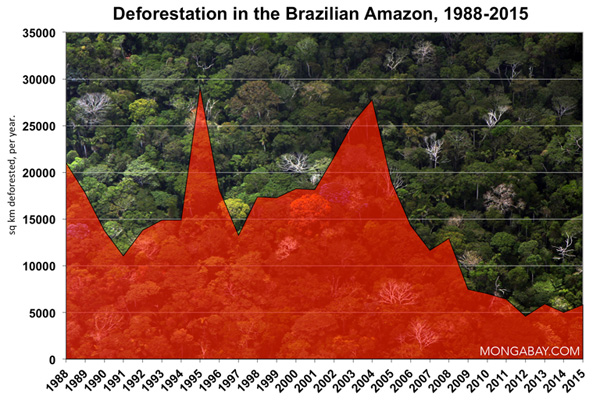

(07/31/2008) Between June 2000 and June 2008, more than 150,000 square kilometers of rainforest were cleared in the Brazilian Amazon. While deforestation rates have slowed since 2004, forest loss is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. This is a look at past, current and potential future drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

More than 8% of the Brazilian Amazon is illegally owned

(06/14/2008) More 42 than million hectares — eight percent — of the Brazilian Amazon is not legally owned, reports a study released last week by a national environmental NGO.

Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon?

(06/06/2007) John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Alianca da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Alianca’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon.

Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

(06/03/2007) The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale, the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belem, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.