Clearing of peatlands in Indonesian Borneo. Photo copyright Greenpeace.

One of the world’s top consultancies, McKinsey & Co., is providing advice to governments developing “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation” (REDD+) programs that could increase risks to tropical forests, claims a new report published by Greenpeace.

The report, Bad Influence – how McKinsey-inspired plans lead to rainforest destruction, says that McKinsey’s REDD+ cost curve and baseline scenarios are being used to justify expansion of industrial capacity in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Guyana.

“While McKinsey’s cost curve has been extremely influential in government policy decisions, it has a number of fundamental flaws,” states the report. “These include data deficiencies and dubious baseline calculations, as well as basic mathematical errors and distortions within McKinsey’s carbon accounting method. Furthermore, McKinsey’s intellectual property rights on some of the data underpinning its cost curve prevent proper scrutiny of its rationale.”

“McKinsey’s approach provides an incentive to over-estimate projected future levels of deforestation, allowing forest nations to claim REDD+ funding for preventing destruction which was unlikely ever to have happened.”

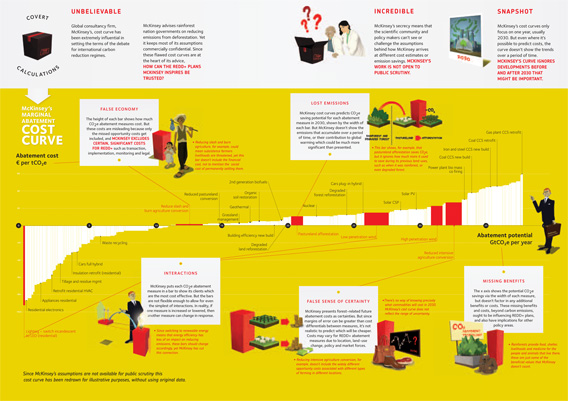

Greenpeace representation of the McKinsey Marginal Abatement Cost Curve

The report highlights Indonesia, where the business-as-usual cost curve developed Indonesian government agencies with input from McKinsey claim plans for increasing pulp and palm oil production will require conversion of 11-15 million hectares of forest, which Greenpeace says “conveniently allows the Indonesian government to claim emissions reductions by putting forward inflated plans and then canceling them.”

“In reality, recent work by Greenpeace has shown how pulp and palm oil production could meet government output targets – without expanding the existing plantation area – by implementing best practice to improve yields, combined with preventing expansion into forest areas.”

Greenpeace also said McKinsey’s cost curve underestimates the actual cost stopping deforestation for subsistence agriculture, making programs targeting smallholders programs look up to thirty times cheaper than stopping industrial conversions of forests.

“The cost curve for Indonesia contains flawed assumptions, which significantly bias the final outcome to protect the interests of industrial forestry and agri-business,” states Bad Influence. “The cost of reducing emission from limiting plantation expansion into natural forests is set as high as possible, by assuming that there are no alternative locations possible – nearly $30/tonne CO2e or $20,000/ha.”

“In contrast, the forecast costs of reducing emissions from smallholder agriculture are minimized to include only the magnetized value for production – a figure of $1/tonne CO2e – which clearly recognizes neither the transaction costs nor more importantly the wider social, environmental and cultural impacts of such an intervention. The effect is to make it seem 30 times cheaper to displace a small farmer, than to challenge the incursion of new plantations into natural forests.”

But McKinsey, which has quickly become a dominant player in the emerging REDD+ advisory sector, defended its work. It said some of Greenpeace’s criticism of its estimates is taken out of context.

“We disagree with the report’s findings and stand firmly behind our work and our approach,” said McKinsey a statement emailed to mongabay.com. “In our work for public-sector clients, we provide a fact-base on the emission-reduction potential from forestry and land-use measures, which can be used to inform complex national debates on equitable low-carbon economic growth strategies.”

McKinsey says it is working with governments to identify low carbon strategies for meeting their development aspirations. These strategies may at times be at odds with environmentalists’ aims.

For example, a report by the National Council for Climate Change (DNPI) on low carbon development options in Central Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) calls for expansion of processing facilities for timber, palm oil, and wood-pulp. The report — upon which McKinsey provided advice, says Greenpeace — argues that increasing the value of land use in Central Kalimantan through higher-value products like processed timber, can lead to higher income for the province while preserving key carbon-rich forests and peatlands.

But Greenpeace says this strategy reflects wishful thinking. Without strong institutions and law enforcement, the activist group believes increased industrial capacity would only boost destruction of forests. It notes that to date, Indonesia has failed to demonstrate much of an ability to stick to land use plans or enforce forestry laws. In fact, the Ministry of Foresty’s reforestation fund has “lost” billions of dollars, including $5.2 billion in just five years (1993-1998). Recent audits have found major forestry firms have failed to pay taxes and acquire required permits for plantation development.

But McKinsey said the abatement cost curve clearly states it does not account for some of the costs necessary to implement REDD.

“Anyone who sat down with a real policy decision-maker would quickly identify many other factors that they need to take into account before introducing a new law,” Per-Anders Enkvist, a partner at McKinsey, told Reuters. “You cannot mechanically translate any abatement cost curve into policy implications, and we have been clear about that in our publications.”

McKinsey told mongabay.com institution-strengthening is important to improving governance and making REDD work. The consulting firm also noted a need for stakeholder participation and dialog, adding Greenpeace did not consult it prior to publishing the new report.

Related articles