An interview with Kirsten Conrad.

Just the mention of the idea is enough to send shivers down many tiger conservationists’ spines: re-legalize the trade in tiger parts. The trade has been largely illegal since 1975 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The concept was, of course, a reasonable one: if we ban killing tigers for traditional medicine and decorative items worldwide then poaching will stop, the trade will dry up, and tigers will be saved. But 35 years later that has not happened—far from it.

“Words such as ‘collapse’ are now being used to describe the [tiger’s] situation both in terms of population and habitat. Wild tiger numbers continue to drop so that we have about 3,500 today across 13 range states occupying just 7% of their original habitat. It’s universally acknowledged that we’re losing the battle,” Kirsten Conrad, tiger conservation expert, told mongabay.com in a recent interview (to read Kirsten’s paper on the subject: Making Sense of the Tiger Farming Debate).

Conrad with baby tiger. Photo courtesy of: Kirsten Conrad. |

In total the tiger population has fallen from an estimated 100,000 at the beginning of century: a more than 95% decline. The statistic is particularly shocking given that the tiger remains one of the world’s most popular animals and has received far more effort and funds for its conservation than most other endangered species.

So, it is obvious from statistics alone, that the CITES ban has not yet saved the tiger. The great cat is still widely poached (a recent study by TRAFFIC finding at least 100 a year), the price for illegal parts has risen and demand seems insatiable, and the tiger appears destined for extinction in the wild. This is not a novel situation: three of the world’s tiger subspecies have vanished forever.

To prevent this fate happening to the rest, next week in St. Petersburg conservationists and government representatives are holding a ‘Tiger Summit’ to approve a last-ditch effort, including hundreds of millions of dollars, for saving the tiger.

“Even though we are spending millions of dollars—and are about to spend hundreds of millions—and many talented and dedicated people are working very hard, we are losing the battle to save tigers because our approach has not been adapted to work effectively in the various countries that are host to the wild tigers and those who consume them,” Conrad says.

But what is to be done? Conrad suggests that the international community look at an option that has long been considered anathema: legalizing tiger parts through controversial tiger farms (where thousands of the big cats are raised in captivity). She does not advise that the idea be implemented immediately, but simply studied. Yet, how could legalizing tiger consumption actually save wild tigers?

“The trade ban has set up a perverse situation where the tiger is worth much, much more dead than alive. That applies for people who live among wild tigers, people who consume them, and the market that connects the two. Until that equation is fixed, the current trajectory will continue,” Conrad explains. “Even more perverse is that the trade ban actually creates a situation that drives additional money into the hands of the black market,”

Conrad points out that the trade in tiger parts is ‘price inelastic’, in other words consumer are willing to pay pretty much anything for the product.

“We know that buyers of tiger bone in China know the tiger is endangered and support the ban, but are still trying to buy tiger products at very high prices. On top of that they risk the death penalty. That’s a strong indication of price inelasticity,” she explains, comparing the ban’s failure to the inefficacy of the American prohibition or the drug trade. Even more similarly, she points out that the ban on elephant ivory and rhino horn has not worked either.

An infant tiger is microchipped in Guilin tiger farm. Photo courtesy of Kirsten Conrad. |

Ending the outright ban and legalizing tiger parts sourced from farms would create competition with the black market, according to Conrad, hopefully drawing down demand for poaching tigers in the wild. Given the dangers of poaching—and its extravagant cost to consumers—legalizing tiger parts may actually stem poaching far faster than enforcement or persuasion ever could.

“My personal view,” says Conrad, “is that an option that may benefit wild tiger populations is being taken off the table without proper evaluation. It’s being taken off the table because, until recently, economics was not factored into wildlife conservation. Even now the role of economics is neither well understood nor even accepted […] Personally, the idea of farming and harvesting tigers is not appealing from an ethical, welfare or even aesthetic point of view. But, if farming offered relief for wild tigers, what do you choose?”

In a November interview Kirsten Conrad talked with mongabay.com about the global failure to stem tiger loss, the economics of the black market, and how legalizing tiger parts from farming could aid—rather than hurt—the world’s largest cat and one of its most magnificent predators.

AN INTERVIEW WITH KIRSTEN CONRAD

Mongabay: What’s your background?

Kirsten Conrad: I studied Asian history in university and have an MBA. My background is in advertising and management consulting and I have worked in the US and throughout Asia. I’ve lived in Asia for 15 years, first in Hong Kong, and now Singapore.

Tiger farm in China. Photo courtesy of Kirsten Conrad. |

Mongabay: How did you become interested in tiger conservation, specifically the controversial idea of ‘tiger farming’?

Kirsten Conrad: I was doing research for my book, Saving Asia’s Wild Cats, which profiles conservation projects for the family Felidae. Such a book would be incomplete without China, which has 12 species. At that time, in 1999, the only conservation work specifically dedicated to cats was the tiger breeding center in Hengdaohezi (Heilongjiang Province, on the border with the Russian Far East). So I went up to see what was going on. It was clear to me that they were breeding more tigers than they needed for tourism and their reintroduction (called ‘rewilding’) plan seemed retrofitted for my visit. But it got me thinking.

Over the years, I watched wild tiger population numbers decline. Each report was accompanied with NGO’s pleading for “more political will” on the part of governments and more funding for their efforts. Although well intended, it became clear that the recipe for tiger conservation just wasn’t working. It also became apparent to me that the fate of wild tigers lay in human hands and had little to do with the tigers themselves.

In 2005, I read an editorial by Cory Meacham, who had written a book on tiger conservation. He said it was time that we seriously consider legalizing trade because the trade ban had simply failed. I’d been wondering this myself, and suggested to TRAFFIC and the Cat Specialist Group that they take a look at legal trade as a conservation option. That went nowhere.

Early the next year I learned that the Chinese government wanted to launch an investigation into the trade ban and asked if I would be interested in assisting them. Since my background is in business, I set about identifying and structuring the economic and market research that would be required to support their decision making. Although I was skeptical at first, I saw how deeply embedded the use of tiger bone was in treating certain ailments (and how little it mattered that people outside of China promoted substitutes). I began to see how a sustainable source of tigers could support in situ tiger conservation.

TIGER CONSERVATION

Mongabay: What is the state of tiger conservation today?

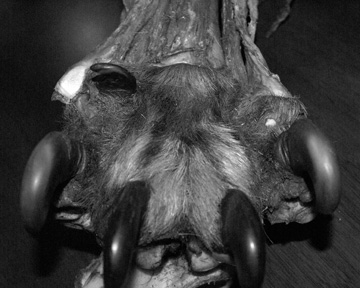

A tooth from a poached Sumatran tiger. Photo by: Brendan Moyle. |

Kirsten Conrad: We know more about tigers and about the issues we face in conserving them, yet we have fewer wild tigers than ever before. Words such as “collapse” are now being used to describe the situation both in terms of population and habitat. Wild tiger numbers continue to drop so that we have about 3,500 today across 13 range states occupying just 7% of their original habitat. It’s universally acknowledged that we’re losing the battle: a recent journal article is titled “Bringing the Tiger Back from the Brink—the Six Percent Solution”.

Alarm after alarm has done little to change the persistent negative trajectory. Every twelve years it is the Year of the Tiger according to the Chinese calendar, and every twelve years there is a huge push by the international conservation community to save the tiger. This time around it is no different, and the World Bank is capping its Global Tiger Initiative with a summit to be held in St. Petersburg this month. The goal is to double the number of wild tigers by the next Year of the Tiger and the price tag of $261 million for the first five years. This is on top of what’s already being spent by range states.

The World Bank program has many good ideas, but the way it plans to deal with the persistent trade in tiger parts is by enforcement and “demand elimination” campaigns. I saw a presentation in a run-up workshop to change people’s attitudes towards wild tiger consumption using Twitter. If the existing death penalty for trafficking in China is not sufficient to stop trade, how is Twitter going to work?

Mongabay: In your opinion how well is the CITES ban working? How do we know demand has not stalled with the ban?

A fake tiger paw for sale. The black market in tiger parts has produced a side-market in fakes. Photo by: Brendan Moyle. |

Kirsten Conrad: That’s easy! If the ban were working, there would not be so much poaching. According to the World Bank Global Tiger Recovery Program, seizures of illegally traded tiger products in range states alone represent about 150 tigers per year, “a figure that is probably several orders of magnitude less than the true level!”. At that rate, we’re looking at no wild tigers by the next Year of the Tiger.

The CITES ban on most tiger sub-species was implemented in 1975 and in 1987 the remaining sub-species was added to Appendix I. The Chinese domestic ban followed in 1993. TRAFFIC surveys in the 1990’s note the presence of residual demand in China, Hong Kong and the US, and a decade later other TRAFFIC surveys note persistent demand and actual use of tiger bone despite an awareness of, and support for, the ban.

Evidence suggests that some tiger products are illegally entering the market from captive populations (including China, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia) and substitutes (other large felids) for tiger bone are being sourced from as far afield as Africa.

It is important to bear in mind that CITES is concerned only with trade, and not other issues that face endangered species conservation, such as habitat, human conflict, and genetic impoverishment. But also bear in mind that poaching may push many wild tiger populations beyond the point of no return before the habitat and other issues can be addressed.

Mongabay: With all the money and support being thrown at the world’s biggest cat why are we still losing tigers in the wild?

Tigers following a food truck in Chinese tiger farm. Photo by: Kirsten Conrad. |

Kirsten Conrad: Even though we are spending millions of dollars—and are about to spend hundreds of millions—and many talented and dedicated people are working very hard, we are losing the battle to save because our approach has not been adapted to work effectively in the various countries that are host to the wild tigers and those who consume them.

CITES operates under the assumption that commercial trade is detrimental to an endangered wild species. Profit is bad. So the trade ban has set up a perverse situation where the tiger is worth much, much more dead than alive. That applies for people who live among wild tigers, people who consume them, and the market that connects the two. Until that equation is fixed, the current trajectory will continue. Even more perverse is that the trade ban actually creates a situation that drives additional money into the hands of the black market.

In Asia, where the tiger lives and is consumed, it is pointless to expect conservation to take place for altruistic, aesthetic, or moral reasons. Conservation is a luxury many countries cannot afford, when feeding a growing population (one which has expanded three-fold since WWII), building an economic infrastructure, education and national security take precedence over conservation. In many range states, conservation is seen as something that has been imposed by the West and is tolerated because it brings in revenue (aid) and “membership”. Tiger conservation is like a Boy Scout’s badge of honor—and even “scoundrel” countries such as Myanmar want one.

TIGER ECONOMICS

Mongabay: How could allowing well-regulated legal trade in tiger parts be beneficial to wild tiger conservation?

Tigers following a food truck in Chinese tiger farm. Photo by: Kirsten Conrad. |

Kirsten Conrad: Well-regulated trade in tiger parts could benefit wild tigers if those people who currently buy parts from wild tigers would switch to a legal source, should it become available.

However, we can’t predict consumer behavior or even make educated guesses because the nature of demand for tiger parts is something we do not know much about. Existing studies have 1) not asked actual users of tiger products about their preferences and 2) not included any price information are therefore not suitable to make predictions regarding consumer behavior. Obviously, an important first step is to find out more about consumers. What motivates and influences buying behavior? What is the demographic profile of consumers? How big are the current and potential markets for captive-bred and wild tigers, and how will that change over time? On the supply side, we have to understand the cost structure of the two markets and work out a pricing strategy that would allow the legal market to compete effectively against the black market.

As it stands now, the black market has a monopoly trade on wild tigers. Legalization of trade would provide a competitor to the black market. And legal trade would have an incentive to “police out” illegal suppliers. A conservation tax could be imposed. But of course there are operational and legal issues that would have to be sorted out, including monitoring and control, welfare (although technically not part of conservation, it is of great concern to many), regulation, and enforcement against illegal supply.

Mongabay: Why is poaching tigers likely more costly than sourcing tiger parts from other non-wild sources, i.e. tigers in captivity?

Tiger feeding in Chinese tiger farm. Photo by: Kirsten Conrad. |

Kirsten Conrad: We do not have a good handle on the total cost to bring a tiger from either wild or captive source to end user. On the face of it, it looks as though poaching is the least expensive way to supply a tiger because the actual poaching cost is low—figures quoted vary from $1 to $200—while the cost to raise a captive-bred tiger is cited as $2,000-$6,000/year.

The cost to poach a tiger, paid to the actual hunter, is certainly less, but there are a number of other costs which must be accounted for. In addition to the cost paid to the actual poacher, these include: processing, smuggling, storage, bribery and protection. A rule of thumb I’ve heard is that every time a consignment changes hands, the price more than doubles because it’s so risky. If you think about a tiger coming out of the jungle, to a trade center, then crossing several international borders, and finally penetrating into China, you see that it might change hands 5-6 times.

We do know that the parts of a single tiger fetch between $30,000 and $70,000 on the Chinese black market. That price reflects the risk of illegally supplying a wild tiger to people who want them. If you take away the risk, then the cost would go down.

Mongabay: What is price-inelasticity? How does this relate to the tiger trade?

Tiger feeding in Chinese tiger farm. Photo by: Brendan Moyle. |

Kirsten Conrad:“Price elasticity” is a measure of how sensitive consumers are to increases or decreases in price. The more “price elastic” something is, the more buyers respond to changes in how much it costs. If it’s cheaper, they buy a lot more and if more expensive, they buy much less. When economists say something is “price inelastic”, they mean that consumers hardly reduce the amounts they buy when the price goes up.

We know that buyers of tiger bone in China know the tiger is endangered and support the ban, but are still trying to buy tiger products at very high prices. On top of that they risk the death penalty. That’s a strong indication of price inelasticity.

Mongabay: What does price-inelasticity mean in terms of the efficacy of increased enforcement against the illegal tiger trade?

Kirsten Conrad: When something is price-inelastic, people will buy it no matter how much it costs. This is frequently the case with addictive, luxury, or goods with perceived medicinal properties. When enforcement is increased, costs such as smuggling, transport, and bribery go up, and it becomes riskier to trade. These cost increases are passed along to consumers, and the illegal trade enjoys higher margins because it takes on more risk. So, increased enforcement not only raises the cost to end consumers, it results in more profits for the illegal trade. Of course, each buyer has his own maximum “willingness to spend” figure and some will drop out of the market. However, we know that people still buy—and stockpile—tiger bone despite costs which we believe are in the $50,000 range and for which they hazard the death penalty.

Mongabay: Do we know if consumers of tiger bone would purchase farmed tiger if wild tiger is still available, albeit at a greater price?

Tiger cub behind bars at tiger farm. Photo by: Eric Conrad. |

Kirsten Conrad: We do not. The biggest unknown is the nature of consumer demand, and as noted, it is meaningless to talk about demand unless you also talk about price. Existing studies have 1) not asked actual users of tiger products about their preferences and 2) not included any price information are therefore not suitable to make predictions regarding consumer behavior.

For example, if you ask a tiger bone consumer if he’d be willing to buy wild tiger bone at $1/kg and then ask again at $100/kg, his answers might be different.

I would also like to add that it is very popular for conservation experts outside of China to hypothesize what they think Chinese consumers want. In this case, they say wild tigers are preferred over captive-bred because they think the Chinese would prefer the more “fierce” alternative.

Mongabay: Why are you not concerned about leakage, i.e. the possibility that trade from captive tigers actually increases the number of poached tigers in the wild?

Kirsten Conrad: If people actually prefer wild tigers, and may even be prepared to pay a premium for them, then it’s hard to see any incentive for laundering them into a legal distribution channel which sells farmed tigers and markets them as such. On the other hand, if trade were legalized, then it would only be non-law abiding citizens who would seek out wild tiger products. What you’re looking to do is lure users—all of whom are currently non-law abiding—into a legal and sustainable market. These users today run the risk of buying counterfeit goods; they may actually prefer to buy certifiably genuine goods.

It is possible to determine genetically the probability that whether a sample came from a certain population or not. Random testing of, say, bone, would indicate the origins of the source.

The other thing to bear in mind is that, from what we know, wild tiger parts make their way from India and Southeast Asia into China, which we believe to be the main consumer country. If trade were legalized in China, most of the pipeline would still occur illegally, and tiger products could only be introduced to the legal supply channel when physically present in China.

Mongabay: Why do trade bans sometimes backfire? What are some other examples beyond tigers?

Kirsten Conrad: The idea behind a trade ban is that once something (be it product or service) is no longer legally available, demand will wither away. The classic example of failure is Prohibition in the US. More current cases involve heroin, cocaine and marijuana. In terms of wildlife, you can also look at rhino horn and ivory. Contraband shipments of ivory turn up on a regular basis.

Restricted supply also pushes up prices which means more money to pay poachers in the case of wildlife.

Mongabay: What information do we still need in order for policy makers and conservationists to make a fully-informed decision relating to tiger farming?

Kirsten Conrad: We definitely need further information to decide if tiger farming, and ultimately lifting the trade ban, will help or hurt wild tiger populations. This option has to be thoroughly investigated, employing the tools of relevant disciplines such as economics. First, we need to undertake a carefully designed consumer survey that, among other things, assesses relative consumer preferences (measured by willingness to pay) between legal certified farmed products and illegal wild product and how the demographics of consumers are likely to change over time. Second, any feasibility study has to scrutinize the issues of keeping farmed and wild products separate, preventing laundering, and channeling a proportion of any profits into wild tiger conservation. Finally, it may be prudent to look at appropriate ways to test the market, such as a carefully designed and monitored one-off sale.

GOING FORWARD

Siberian tiger in a tiger farm. Photo by: Brendan Moyle. |

Mongabay: Why should we keep China’s tiger farms open?

Kirsten Conrad: The farms are an insurance policy.

In terms of poaching, there is evidence that some demand is being met with “leakage” from the farms. If you close down the farms, then you risk sending those consumers to the wild market. How does that make sense?

In terms of conservation science, one of the tiger farms has a population of about 1,000 genetically pure Amur tigers. This farm is attached to the Northeastern Forestry University, and this world’s largest, contiguous population gives an opportunity to perform genetic studies. There is also the possibility of reintroduction—if American and European zoos have tiger “arks”, then why not China? The recent news that a wild Siberian tiger in Russia has died from canine distemper underscores this point.

Mongabay: What is your personal view on re-installing a legal trade in tiger parts?

Kirsten Conrad: My personal view is that an option that may benefit wild tiger populations is being taken off the table without proper evaluation. It’s being taken off the table because, until recently, economics was not factored into wildlife conservation. Even now the role of economics is neither well understood nor even accepted.

The fate of wild tigers lies in human hands, and this is why I have been promoting the use of economics—in addition to the existing work—because it looks at how humans behave in allocating allocate scare resources. Tigers are certainly a scarce resource. Until we understand how humans behave, and therefore how to motive and change their behaviors, we’re going to continue to lose the tiger war. This means collecting data and facts, performing proper and rigorous studies, and then integrating the economic work with natural science and law enforcement. It would be a shame to lose tigers because of human opinions and politics.

Personally, the idea of farming and harvesting tigers is not appealing from an ethical, welfare or even aesthetic point of view. But, if farming offered relief for wild tigers, what do you choose?

Mongabay: How does the legal trade in bears for traditional Chinese medicine point towards the at least partial efficacy of a legal trade aiding wild animals?

Kirsten Conrad: I’m not aware of any definitive studies that look at the impact of bear bile farming on wild populations; the same goes for musk deer. As far as I know, opinions on the impact of bear farming on wild populations vary. This point is disputed, with some groups claiming that bears are still being poached despite the existence of farms in China and Vietnam, with others insisting that poaching of wild bears has declined due to the existence of farms in China, Vietnam, and Korea.

Mongabay: In the long-term is the battle really about the beliefs and customs of Southeast Asian customers?

Hybrid tiger diving in Guilin Chinese tiger farm. Hybrid tigers (combined subspecies) are sometimes euthanized by zoos, given that they are considered ‘unusable’ for conservation efforts. Photo by: Brendan Moyle. |

Kirsten Conrad: That’s a loaded question, but an excellent one. In my ten+ years working in tiger conservation, I find the prevailing belief outside of Asia to be that: “when these countries/people become more developed (i.e. “civilized”), they’ll start to think like us.” In terms of tiger or many animal-based remedies, while we assert that there is no medical basis for these things to work, what we believe doesn’t really matter. Whether we can change those beliefs, indeed whether it’s even right for us to try and “educate” them, is another question.

It also comes down to the question of “who really owns the tigers?” And that’s tough, because tigers are supplied illegally from almost every range state, and funds to protect those tigers come from around the world.

Mongabay: How could organizations work to increase the stigma of buying illegal tiger parts?

Kirsten Conrad: Not just organizations, governments too. Organizations can work on the “soft” side, informing people about the impact their consumption has on wild tigers and promoting alternatives. Governments can see that a “loophole” free legal framework exists to support a trade ban, and then enforce that to the best of their ability. (I say to the best of their ability because, let’s face it, many tiger range states have very limited resources, which forces hard choices). In terms of enforcement, among other things organizations can provide infrastructure for knowledge sharing, technical expertise, and training.

We don’t know a lot about how the stigma effect relates to trade ban in endangered species, and we don’t even know if a “reverse stigma ban” is at play. In a “reverse stigma ban”, the difficulty of obtaining the product may actually enhance its desirability.

Mongabay: For many people the idea of making tiger parts legal again is immoral and thereby anathema. What do you say to this?

Kirsten Conrad: According to whose morality? And who has the right to impose his or her morality upon others? This argument can be extended to keeping wild animals in captivity. It’s important to separate animal welfare from conservation. Frequently their concerns overlap, but not always. In terms of wild tiger conservation, the more relevant concern is what impact legalization might have on wild tiger populations.

Related articles

Authorities confiscated over 1000 tigers in past decade

(11/09/2010) Highlighting the poaching crisis facing tigers, a new report by the wildlife trade organization, TRAFFIC, found that from 2000-2010 authorities have confiscated the parts of 1,069 tiger individuals, many of them dead. The tigers, or their body parts, were confiscated from 11 of the species’ 13 range countries, according to the report entitled Reduced to Skin and Bones. Yet the number only hints at the total number of tigers (Panthera tigris) vanishing in the wild due to the illegal trade in tiger parts for traditional Asian medicine and decorative items, such as skins.

Tiger farming and traditional Chinese medicine

(06/27/2010) The number of wild tigers has plummeted from 25,000-30,000 animals 50 years ago to around 3,200 today. A large part of the drop is from habitat loss and fragmentation. Tiger habitat has been reduced by 40 percent over the last decade, and tigers now occupy less than 7 percent of their historical range. Poaching has also contributed significantly to these dramatic population declines, particularly to supply parts for use in traditional medicine. In an interview with Laurel Neme, Grace Ge Gabriel, Asia Regional Director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), notes that, although the Chinese government has made significant efforts to reduce demand for tiger products by eliminating tiger bone from the official pharmacopeias, raising consumer awareness and identifying cheaper and more effective herbal alternatives to tiger bone for use in TCM, tiger farms threaten to reopen demand for tiger products by breeding tigers excessively, stockpiling tiger carcasses, and stoking demand by making and selling wine made from tiger bone.

Video: camera trap catches bulldozer clearing Sumatran tiger habitat for palm oil

(10/14/2010) Seven days after footage of a Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) was taken by a heat-trigger video camera trap, the camera captured a bulldozer clearing the Critically Endangered animal’s habitat. Taken by the World Wildlife Fund—Indonesia (WWF), the video provides clear evidence of forest destruction for oil palm plantations in Bukit Batabuh Protected Forest, a protected area since 1994.

Interpol pounces on tiger traffickers

(10/11/2010) INTERPOL, the world’s largest international police organization, is stepping up the fight to end the illegal tiger trade.

Hope remains for India’s wild tigers, says noted tiger expert

(09/30/2010) As 2010 marks ‘The Year of the Tiger’ in many Asian cultures, there has been global interest in the long-term viability of tiger populations in the wilds of Asia. Due to increasing pressures on remaining tiger habitats and a surge in demand for tiger parts from traditional medicine trades, many conservation experts consider the current outlook for wild tiger populations bleak. Dr Ullas Karanth of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) India does not share this view. He believes that a collaboration of global and local interests can secure a future for tigers in the wild.

Tigers successfully reintroduced in Indian park

(09/27/2010) Poachers killed off the last Bengal tiger in India’s Sariska Tiger Reserve in 2004. Four years later, officials transferred three tigers from Ranthambhore National Park to Sariska in an attempt to repopulate the park with the world’s biggest feline. A new study in mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science evaluates the reintroduction by tracking radio-collared tigers and studying their scat.

Tigers discovered living on the roof of the world

(09/20/2010) A BBC film crew has photographed Bengal tigers, including a mating pair, living far higher than the great cats have been documented before. Camera traps captured images and videos of tigers living 4,000 meters (over 13,000 feet) in the tiny Himalayan nation of Bhutan.

Saving wild tigers will cost $82M/year

(09/15/2010) The cost of maintaining the planet’s 3,500 remaining wild tigers is around $80 million a year, according to a new study published in the journal PLoS Biology.

Guilty verdict over euthanizing tigers in Germany touches off debate about role of zoos

(08/11/2010) In June a German court handed down a guilty verdict to the Magdeburg Zoo director, Kai Perret, and three employees for euthanizing three tiger cubs in 2008. The zoo decided to kill the cubs when it was discovered that the cubs’ father was not a 100 percent Siberian tiger (i.e. he was a mix of two different subspecies). This is generally standard practice at many zoos around the world as animals that are not ‘genetically pure’ are considered useless for conservation efforts. However, the court found the workers guilt of breaking animal rights laws, finding that there was “no sufficient reasons to kill less valuable, but totally healthy animals.”

Myanmar creates world’s largest tiger reserve, aiding many endangered Southeast Asian species

(08/04/2010) Myanmar has announced that Hukaung Valley Tiger Reserve will be nearly tripled in size, making the protected area the largest tiger reserve in the world. Spanning 17,477 square kilometers (6,748 square miles), the newly expanded park is approximately the size of Kuwait and larger than the US state of Connecticut.

Dangerous and exploitative: a look at pet wild cats

(07/13/2010) From bobcats, lynx, and pumas to the thousands of lions, tigers, leopards, cheetahs, and little wildcats living in captive environments, the WildCat Conservation Legal Aid Society is solely devoted to ending the commercial exploitation of all wildcats. Its primary objectives are to drastically reduce and subsequently eliminate the private ownership of wildcats as pets; wildcats held in roadside zoos and pseudo-sanctuaries; using wildcats for entertainment purposes; as well as hunting, trafficking, and trade of wildcats. Lisa Tekancic is an attorney in Washington, DC and founder and president of WildCat Conservation Legal Aid Society. Their mission is to protect and defend all native and non-native wildcats. Lisa is an active member of the DC Bar’s Animal Law Committee and has organized and moderated two legal conferences: ‘Trafficking, Trade, and Transport of Wildlife,’ and ‘Wildlife and the Law.’ She presented a paper on the methodology of ‘Animal Ethics Committee’ for the International Conference on Environmental Enrichment, and for four years was volunteer staff at the National Zoological Park’s, Cheetah Station.

Plight of the Bengal: India awakens to the reality of its tigers—and their fate

(06/06/2010) Over the past 100 years wild tiger numbers have declined 97% worldwide. In India, where there are 39 tiger reserves and 663 protected areas, there may be only 1,400 wild tigers left, according to a 2008 census, and possibly as few as 800, according to estimates by some experts. Illegal poaching remains the primary cause of the tiger’s decline, driven by black market demand for tiger skins, bones and organs. One of India’s leading conservationists, Belinda Wright has been on the forefront of the country’s wildlife issues for over three decades. While her organization, the Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI), does not carry the global recognition of large international NGOs, her group’s commitment to the preservation of tigers, their habitat, and the Indian people who live with these apex predators, is one reason tigers still exist.

The Critically Endangered South China Tiger Roars Again in 2010, the Chinese Year of the Tiger

(02/14/2010) Today marks the Chinese New Year for 2010, and the start of the traditional Year of the Tiger. The people of China might be celebrating future Years of the Tigers without their native and critically endangered South China Tiger (Panthera tigris amoyensis) if not for the efforts of Save China’s Tigers (SCT) a grassroots conservation effort headed by the charismatic Li Quan and her husband Stuart Bray. Both Ms Quan and Mr. Bray are former senior executives in international business circles. After leaving the corporate world, Ms Quan and Mr. Bray are now stepping up as champions for China’s natural environment, much of which has been lost in the Chinese march towards “The Four Modernizations.”

Tiger success story turns bleak: poachers decimating great cats in Siberia

(10/18/2009) There were two bright spots in tiger conservation, India and Russia, but both have dimmed. Last year India announced that a new survey found only 1,411 tigers, instead of the previous estimation of 3,508, and now Russian tigers may be suffering a similar decline. The Siberian Tiger Monitoring Program—a collaboration between the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and several Russia government organizations—has found evidence that after a decade of stability the Siberian tiger’s population may be falling. This year’s annual survey, which covers only a portion of tiger habitat in Russia, found only 56 adult tigers: a forty percent decrease from the average of 95 tigers. While the cause of this year’s decline may be weather-related, researchers fear something far more insidious is going on.

Saving the last megafauna of Malaysia, an interview with Reuben Clements

(09/15/2009) Reuben Clements has achieved one success after another since graduating from the National University of Singapore. Currently working in peninsular Malaysia, he manages conservation programs for the Endangered Malayan tiger and the Critically Endangered Sumatran Rhino with World Wildlife Fund. At the same time he has discovered three new species of microsnails, one of which was named in the top ten new species of 2008 (a BIG achievement for a snail) due to its peculiar shell which has four different coiling axes. ie7uhig

Tiger brutally killed in zoo, body parts taken to sell for Chinese medicine

(08/25/2009) Poachers broke into the Jambi Zoo on Saturday morning in Indonesia. Using meat they drugged a female Sumatran tiger named Sheila and then skinned her in the cage. They left behind very little of the great cat: just her intestines and a few ribs. Authorities suspect that the tiger’s body parts will be sold in the thriving black market for Chinese medicines where bones are used as pain killers and aphrodisiacs.