The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a body that has devised certification criteria to improve the social and environmental performance of palm oil, opens its annual meeting tomorrow in Jakarta.

High on the agenda for the meeting are several contentious issues, including the RSPO’s handling of complaints against non-compliant members, stricter financing rules proposed by the World Bank for palm oil producers, and accounting of greenhouse gas emissions from palm oil production. Palm oil marketing bodies tend to maintain theirs is a low-carbon product, but environmentalists say growers often fail to account for emissions resulting from initial conversion of forest or peatlands to oil palm plantations. A consensus on carbon accounting is unlikely to form at the meeting, but some participants are expected to highlight their own voluntary accounting mechanisms as potential paths forward for the industry.

|

The involvement of smallholders in the RSPO will take center stage in the meeting. Smallholders control a significant proportion of the oil palm estate, but their plantations tend to underperform big holdings by most measures, including environmental protection and yield, due to poor practices and substandard genetic material of their palm trees. Smallholders often lack the capacity, knowledge, and funds to get their holdings certified under RSPO, and therefore the body is considering a fund that would subsidize the cost of auditing. RSPO may also evaluate measures to help improve smallholder yields to the level seen on private and government-run plantations, a push which could provide a significant boost palm oil production, especially in Indonesia, without the need to expand the extent of plantations.

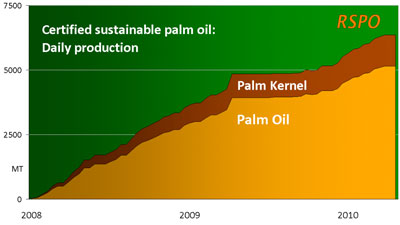

According to Reuters, RSPO-certified palm oil has accounted for more than seven percent of 45 million metric tons in global annual output since the first shipments left port two years ago. Demand for certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) is now roughly meeting supply, according to data from the RSPO.

Palm oil

|

Global palm oil consumption stands at nearly 50 million tons per year, about half of which is traded internationally. It is used widely in processed foods, cosmetics, and soaps — WWF estimates that palm oil is found in roughly half of packaged supermarket products. It is also increasingly used as a biofuel.

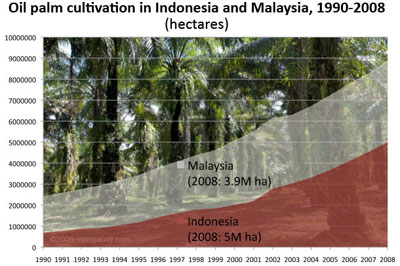

But while palm oil is a highly efficient crop, surging production over the past 20 years has spurred strong backlash from environmentalists who note its expansion has consumed vast areas of rainforest in Malaysia and Indonesia, triggering substantial greenhouse gas emissions and putting endangered wildlife—including orangutans, pygmy elephants, Sumatran rhinos and tigers—at risk. Oil palm plantation development has also exacerbated social conflict in some areas.

Oil palm plantation and logged natural forest, Sabah, Malaysia. Photo: R. Butler/mongabay.com |

The RSPO emerged as a response to these concerns. The body—which includes industry stakeholders as well as environmentalists and other groups—sets sustainability criteria for palm oil production. Nevertheless the initiative has been battered over the past year with revelations that some members have continued to destroy ecologically sensitive habitats. Prominent members, including Unilever and Nestle, have had to act outside the RSPO process to address misconduct by RSPO-member suppliers. Some critics say the scheme lacks oversight, sets a low bar for compliance, and is underfunded. Supporters argue that RSPO is still a relatively new initiative that needs more time to prove itself. The RSPO recently censured a member—PT SMART—which had failed to comply with the body’s rules. SMART, which has lost a number of major clients including Unilever, Kraft, Burger King, and Nestle, is now working to clean up its operations.

Indonesia and Malaysia account for nearly 90 percent of palm oil production.

Related articles

Video: Dutch to ban unsustainable palm oil by 2015

(11/05/2010) Mongabay.com’s Rhett Butler reviews what happened this week in forest news, including the decision by The Netherlands to ban non-certified palm oil from its markets in 2015.

Misleading claims from a palm oil lobbyist

(10/23/2010) In an editorial published October 9th in the New Straits Times (“Why does World Bank hate palm oil?”), Alan Oxley, a former Australian diplomat who now serves as a lobbyist for logging and plantation companies, makes erroneous claims in his case against the World Bank and the International Finance Corp (IFC) for establishing stronger social and environmental criteria for lending to palm oil companies. It is important to put Mr. Oxley’s editorial in the context of his broader efforts to reduce protections for rural communities and the environment.

Corporations, conservation, and the green movement

(10/21/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more poignant. Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Until recently deforestation has been driven mostly by poverty—poor people in developing countries clearing forests or depleting other natural resources as they struggle to feed their families. Government policies in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s had a multiplier effect, subsidizing agricultural expansion through low-interest loans, infrastructure projects, and ambitious colonization schemes, especially in the Amazon and Indonesia. But over the past two decades, this has changed in many countries due to rural depopulation, a decline in state-sponsored development projects, the rise of globalized financial markets, and a worldwide commodity boom. Deforestation, overfishing, and other forms of environmental degradation are now primarily the result of corporations feeding demand from international consumers. While industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and environmental groups. Thus in recent years, it has become easier—and more ethical—for green groups to go after corporations than after poor farmers.

The Nestlé example: how responsible companies could end deforestation

(10/06/2010) The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?

Nestle’s palm oil debacle highlights current limitations of certification scheme

(03/26/2010) Last week Nestle, the world’s largest food processor, was caught in a firestorm when it attempted to censor a Greenpeace campaign that targeted its use of palm oil sourced from a supplier accused of environmentally-damaging practices. The incident brought the increasingly raucous debate over palm oil into the spotlight and renewed questions over an industry-backed certification scheme that aims to improve the crop’s environmental performance.

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.