Early pregnancies prepare a cheetah for a life of productive motherhood, new research shows. A study published on 20 September in Conservation Letters advises captive breeding programs to focus on breeding female cheetahs at young ages to set the stage for many litters throughout their lives.

The world’s fastest animal, the cheetah has not outpaced a disheartening march toward extinction. Populations have declined from an estimated 100,000 a century ago to about 13,000 today. For years, researchers have pointed to the high genetic similarities among individual cheetahs as the main reason why captive cheetahs don’t often get pregnant.

“But if it was truly genetic, then wild cheetahs should have the same problem,” the study’s lead author, Bettina Wachter of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Berlin, Germany, told mongabay.com.

|

|

Instead, the team’s field research showed that free-ranging cheetahs have many healthy litters if they breed starting at age three—much younger than typical first-litter ages in captivity.

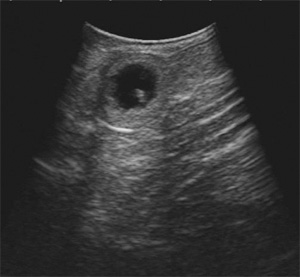

Wachter and her colleagues captured 18 free-ranging female cheetahs in the open farmlands of Namibia and fitted them with GPS collars for tracking. After immobilizing the animals, researchers examined their reproductive organs with ultra-sonography—the same technique used to view human fetuses. By repeating the process with 15 captive female cheetahs, the scientists compared the reproductive health of both groups.

All of the wild cheetahs were in estrous, pregnant, or lactating: signs of active, healthy reproductive systems. About 40% of the captive adult females had active cycles. In the rest of the females, the team concluded that oestrogens—the hormones that control cycling—were impairing or “wearing out” the reproductive organs. Pregnancy and lactation give the organs a rest and promote fertility.

|

|

Most of the wild cubs in the team’s study survived, suggesting that genetic defects are not as serious as other scientists have feared, Wachter said. Rather, lions and hyenas probably kill most cubs in other parts of Africa, such as the Serengeti. Those predators are absent from the team’s study site in Namibia.

The team also tested whether the stress of being fenced in makes captive cheetahs breed poorly, a factor proposed by other scientists. Wachter’s group measured the sizes of their cheetahs’ adrenal glands, which release adrenaline and grow larger when an animal feels chronic stress. The researchers found no difference in the glands of the captive and free-ranging cheetahs.

The combined results point toward early reproduction as the key to keeping cheetahs fertile, regardless of where they live, Wachter said.

“In the wild, cheetahs have their first litter at about three years, while captive cheetahs often are not bred until they are six, seven or eight,” she said. “If these animals are intended to be breeders reintroduced to the wild, this will have to change.”

|

|

The results could inform captive breeding programs in the United States and elsewhere as they seek to boost cheetah numbers. Ironically, breeding captive cheetahs in Namibia is illegal for political reasons.

A forthcoming independent study also found that a cheetah’s reproductive system wears out more quickly if the animal has never been pregnant, said wildlife biologist Adrienne Crosier of the Cheetah Science Facility at the National Zoological Park in Front Royal, Virginia.

“I completely agree that the reason we often fail to reproduce cheetahs in captivity is that we wait too long with the females,” Crosier told mongabay.com.

CITATION: Bettina Wachter, Susanne Thalwitzer, Heribert Hofner, Johann Lonzer, Thomas B. Hildebrandt and Robert Hermes. Reproductive history and absence of predators are important determinants of reproductive fitness: the cheetah controversy revisited. Conservation Letters published online 20 September 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00142.x

Danielle Venton is a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Related articles

On the Road with Dr. Laurie Marker: Reflections on Conservation in the Media Age

(07/26/2010) Earlier this year, mongabay.com had the opportunity to interview world-renown conservationist Dr. Laurie Marker, Executive Director and Founder of the Namibia-based Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF). Dr. Marker had just received the prestigious Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement from the University of Southern California and was traveling throughout the US on one of her many international public relations tours.

India hopes to reintroduce cheetah 60 years after extinction

(07/09/2009) India hopes to reintroduce the world’s fastest land animal some 60 years after it went extinct in the country, reports The Independent. India’s Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh said the government has commissioned a study to determine whether it is possible to reintroduce the cheetah into India by importing pairs from Namibia.

Cheetah population stabilizes in Namibia with support from farmers

(10/02/2008) Viewing the world’s fastest land animal as a threat to their livestock, in the 1980s farmers killed half of Namibia’s cheetah population. The trend continued into the early 1990s, when the population was diminished again by nearly half, leaving less than 2,500 cheetah in the southern African country. Today cheetah populations have stabilized due, in large part, to the efforts of the Cheetah Conservation Fund, an organization founded by Dr. Laurie Marker.

Cheetah population declines 90% in 100 years

(09/30/2008) The planet’s fastest land animal is falling behind in its race for survival against habitat encroachment, loss of prey, the illegal wildlife trade, and disease. Once found widely across the African continent to Kazakhstan in the north to Burma in the East, the cheetah has seen a dramatic reduction of its range and numbers in recent centuries as livestock holders have relentlessly killed off the cat as a threat to their livelihoods. Today the cheetah clings to strongholds in only a few African nations. Among these is the southern African country of Botswana, which harbors large expanses of prime cheetah habitat. Still even in Bostwana, the cheetah faces challenges.