An interview with Scott Poynton of The Forest Trust.

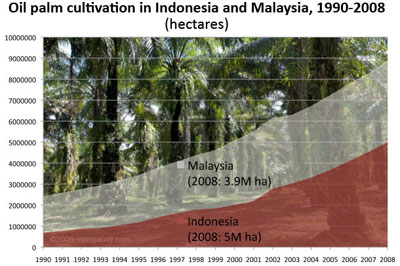

The NGO, The Forest Trust (TFT), made international headlines this year after food giant Nestlé chose them to monitor their sustainability efforts. Nestlé’s move followed a Greenpeace campaign that blew-up into a blistering free-for-all on social media sites. For months Nestle was dogged online not just for sourcing palm oil connected to deforestation in Southeast Asia—the focus of Greenpeace’s campaign—but for a litany of perceived social and environmental abuses and Nestlé’s reactions, which veered from draconian to clumsy to stonily silent. The announcement on May 17th that Nestlé was bending to demands to rid its products of deforestation quickly quelled the storm. Behind the scenes, Nestlé and TFT had been meeting for a number of weeks before the partnership was made official. But can TFT ensure consumers that Nestlé is truly moving forward on cutting deforestation from all of its products?

“Our goal is to help businesses bring Responsible Products—those that respect the environment and improve people’s lives throughout the whole supply chain—to market,” the creator and director of TFT, Scott Poynton, told mongaby.com recently. With an education and background in forestry, Poynton has years of inside knowledge into the challenges and opportunities for big companies securing ‘responsible forestry’ products. Poynton says his brainchild, TFT, works differently than most NGOs concerned with social and environmental issues.

Scott Poynton. Photo by: TFT. |

“We focus on products—period. We don’t spend a lot of time in workshops; we don’t work on global policies. We work on the ground, up to our neck in dust, mud, flies, mosquitoes, right at the coal face to make things better,” Poynton says, adding that “if you accept that it is the product supply chains causing the world’s problems—see the [popular on-line video] the Story of Stuff—then we think ours is a logical approach.”

In fact, with its on-the-ground work with supply chains for big and small companies, TFT works closely with the private sector—rather than protesting it—to make their products more environmentally and socially responsible.

“We have private sector backgrounds, we understand supply chains, we’re passionate about our members’ products and their businesses,” Poynton stresses. “But we’re passionate about people and the environment too and believe we can be best in the world at helping businesses deliver responsible products. That’s unique I think.”

Nestlé’s commitment is notable for several reasons according to Poynton: first off, the company has moved beyond many of its competitors by pledging to rid its products of deforestation entirely—not just forest destruction linked to palm oil.

“Think about that for a moment and what this could mean. This is not just a palm oil issue for Nestlé; rather it’s about all their products. They don’t want any part of their business to cause deforestation. We’ve started on palm oil but we’re now also looking at all their pulp and paper procurement. Beyond that, and in time once we’ve made progress on palm oil and pulp and paper, there’s a commitment from the company to look at the life-cycle of all their products with a view to tackling any deforestation footprints,” Poynton says, adding, “imagine if every company in the world took the same stance.”

Nestlé is not wholly alone in this goal, the French market chain and TFT member, E. Leclerc, has made a similar commitment. Poynton sees such decisions as the beginning of a movement, which, if supported, could more effectively halt deforestation than any government policy.

|

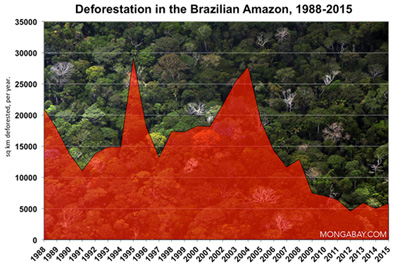

“If we can get the largest companies and the smallest companies to follow the Nestlé example and say ‘No Deforestation!’ I believe we’ll see a dramatic and immediate decrease in deforestation; much more rapidly than any global policy forum could achieve. That’s because business moves fast and millions are made and lost on the basis of products meeting buyers specs. If the specs say ‘No deforestation’ and are truly implemented—bang, immediate impact,” Poynton says.

But TFT hasn’t just broken ground with European companies, they have even made progress in one of the most difficult places to tackle social and environmental issues head-on: China. Recently, TFT has worked with a plywood manufacturer in China to clean-up their supply line by seeking legally-verified sources of wood.

“Chinese businesses are no different from businesses elsewhere—their primary objective is profit and at TFT we’re comfortable with that. If delivering Responsible Products is more profitable than delivering illegal ones, then Chinese companies (and all other companies the world over) will be happy to abide by any guidelines. The tipping point in this case depends on whether UK customers buy this legally verified plywood,” Poynton says, highlighting the role of consumers in supporting companies that are environmentally responsible.

“Our work is transformative; if you want Business as Usual, don’t work with TFT. But if you want to get deforestation out of your products, this Chinese achievement shows it’s possible,” says Poynton.

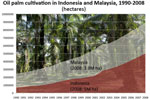

Click to enlarge |

While Poynton’s vision is one rarely discussed among policymakers, environmental groups have been pushing for companies to take responsibility for their environmentally-degrading actions for decades. However, deepening concerns about climate change, mass extinction, and continuing deforestation, along with new tools—like social media sites—may make this the perfect time for businesses to wake up to a greener world. TFT sees itself as instrumental in helping companies make the transition. The question is: are consumers ready to demand, really demand, products free from deforestation?

“If big markets around the world, but also in Asia, understand that chopping forests down is not such a good thing and then follow the Nestlé lead of saying ‘No deforestation in our products please’ then we really can make a huge impact. We could change not only the palm oil product story, but the whole story surrounding global deforestation. I believe we’re poised at a very critical tipping point.”

In an October interview with mongabay.com Scott Poynton discussed The Forest Trust’s mission, its recent partnership with Nestle, its work in China, the issue of over-consumption, and how in a best-case-scenario changing the way the private sector sources their products could make large-scale deforestation a thing of the past.

AN INTERVIEW WITH SCOTT POYNTON

Mongabay: What’s your background?

Scott Poynton: I’m an Australian forester who grew up in what was then a rural part of Victoria but that has since been over-run by Melbourne’s suburban sprawl. I spent a lot of my youth playing in and around forests and decided at age 14 that a career in forestry was for me having heard Sir Richard Baker (Founder of Men of the Trees) speak on ABC Radio about his experiences trying to establish trees in Kenya in the 1920s. Sir Richard spoke about the wonder of forests and the need to sustainably manage and conserve them in such an infectious way that I was captivated from that moment on.

Teak plantation run by TFT. Photo by: TFT. |

I studied forestry at the Australian National University in Canberra and one summer had the luck to work in Nepal on the Nepal-Australia Community Forestry Project. Those 3 months was a test of whether my passion for forestry could be translated into work overseas and it turned out that I absolutely loved it. I then worked in Forestry in Tasmania for a number of years to get some excellent practical experience before completing an MSc in Forestry at Oxford Forestry Institute in 1990-91. That led me to Vietnam where I worked on an aid project researching the best way to reforest a big area of acid-sulphate soils that had been cleared of their rich Melaleuca forests at the end of the Vietnam War for rice production. The rice had failed and so the Government wanted to reforest the land in partnership with communities, so it was a really rich experience.

On return from Vietnam in 1995, I continued to work in overseas forestry as a consultant travelling extensively across Southeast Asia. This was an enlightening time where I learnt a great deal and saw that many of those being castigated as forest destroyers were actually very interested in sustainable forest management but just didn’t know how to do it. I moved to the UK in 1997 where, in response to a big campaign against garden furniture, I founded The Forest Trust (TFT) with a close colleague (Bjorn Roberts) and then found myself going back to Vietnam to work as the MD of ScanCom Vietnam, one of TFT’s Founding members. I managed the company’s operations for two years and helped introduce Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) Eucalyptus garden furniture to the global market. That was a great two years as I learned a lot about buyers and retailers—the business side of the wood industry and one that too often, young foresters don’t get exposed to and hence don’t understand. Since 2001 when I left ScanCom, I’ve been running TFT.

Mongabay: What prompted you to help establish The Forest Trust?

Woman in Congo TFT project utilizing wood for medicine. Photo by: TFT. |

Scott Poynton: In December 1995, I was asked by SGS [an FSC-accredited certification provider] to be their technical advisor on a full FSC assessment of a forest in Vietnam. The audit was being conducted for B&Q, an FSC Founding member who hoped to be first to market with FSC garden furniture. Their problem was that there was no FSC wood available for garden furniture production in Southeast Asia so they were working with their supplying factory to create it. The audit turned out to be a disaster—it’s a long story—and B&Q sought to disengage from Vietnam. I urged Alan Knight, their Sustainability Director, to stick with the country but to approach their sourcing differently: rather than let the factory buy the wood on the open market, I suggested that B&Q take their supply chain controls right back to the forest source. If they could identify a forest with the right volumes of the right species, they could direct their supplying factory to buy wood from ONLY that forest. With a robust traceability system in place, they could then finance technical assistance to the forest managers to help them achieve FSC certification so that B&Q could move away from untraceable wood, to wood from known legal sources, to wood moving to FSC to FSC certified wood all with a single forest. This was the creation of The Forest Trust model though at that stage TFT as an institution did not exist to house it.

Alan thought it a good plan and we embarked on the search for a forest. It took longer than expected—another long story—and B&Q lost their appetite to engage as they needed FSC furniture and sought it elsewhere. Eventually a forest was found in early 1998 and the timing was perfect because it coincided with the release of the seminal report from Global Witness “Made in Vietnam, Cut in Cambodia” which highlighted that much of the mass produced garden furniture being exported from Vietnam to Europe was made using wood illegally harvested with human rights abuses in Cambodia. This created a huge stir in Europe. Campaigning NGOs hit major retailers who turned to their suppliers for a solution. None had one—they had absolutely no idea where their wood came from because they didn’t control the sourcing; their Contract Manufacturing factories did and even they didn’t know because they bought it from a complex system of traders and middlemen famous for keeping their sources secret.

Many of the large retailers had a common large supplier—ScanCom—and the company’s owner came up with a plan to raise funds to do something to turn the situation around. He wasn’t sure what action was needed but he knew it required money so he decided to put a 2% levy on the furniture. He went to WWF UK with his plan who directed him to speak to me—I had the forest, he needed its wood. I needed money to finance the work to move it to FSC, he had the funds from the 2% levy and so we, together with 6 of his customers (the Jysk Group across Scandinavia and Germany and Kwantum in the Netherlands) agreed to establish TFT.

Mongabay: What is your organization’s goal?

Scott Poynton: It’s changed since our inception. Back then we wanted to exclude illegal wood from products, replace it with FSC wood and raise awareness amongst consumers. Today our goal is to help businesses bring Responsible Products—those that respect the environment and improve people’s lives throughout the whole supply chain—to market. We’re a charity and our belief is that product supply chains are causing all the environmental destruction and social disenfranchisement we see today so let’s work with product supply chains to find solutions.

Mongabay: What makes The Forest Trust different from other organizations?

TFT project working with local villagers in the Congo to learn GPS. Photo by: TFT. |

Scott Poynton: Two key things: we’re different because we focus on products—period. We don’t spend a lot of time in workshops; we don’t work on global policies. We work on the ground, up to our neck in dust, mud, flies, mosquitoes, right at the coal face to make things better. If you accept that it is the product supply chains causing the world’s problems—see the Story of Stuff—then we think ours is a logical approach. It means we’re staffed by very different people compared to other NGOs; we have private sector backgrounds, we understand supply chains, we’re passionate about our members’ products and their businesses. But we’re passionate about people and the environment too and believe we can be best in the world at helping businesses deliver responsible products. That’s unique I think.

And we’re different because our members fund our work in their supply chains. Our members take responsibility for what happens along the full length of their supply chains and invest in technical assistance for their supply chain partners to get it right. Few companies outside our members do this. They invest in product development e.g. new designs, new manufacturing processes, new ways to reduce cost. Our members fund our work right back at the raw material extraction phase to ensure that the raw materials used to make their products meet their specifications.

NESTLE

Mongabay: The Forest Trust recently made international news when Nestle, after a campaign by Greenpeace linked it to deforestation in Indonesia, came to you to help set-up a system to audit their palm oil supply. How did Nestle approach you?

Scott Poynton: We approached each other really. As we’re located just down the lake from Nestlé here in Switzerland, I’m fortunate enough to know a number of their staff. I’d often mentioned to my Nestlé colleagues that I felt that TFT could help them look at Responsible Products and when the Greenpeace campaign broke on March 17th, I contacted one of my friends and said that I really felt that I could assist. He put me in touch with senior people there, we met and discussed the work that we both felt needed to be done, found great common ground and announced our partnership on May 17th.

Mongabay: What was ground-breaking about Nestle’s move?

Beginning of the palm oil plantation in the foreground in Sumatra, Indonesia, forested hills in the back. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Scott Poynton: There were a number of groundbreaking things about Nestlé’s move. First and foremost, and not really captured by the press after the announcement of our partnership, was Nestlé’s commitment to remove any deforestation footprint from their products. All of their products. Think about that for a moment and what this could mean. This is not just a palm oil issue for Nestlé; rather it’s about all their products. They don’t want any part of their business to cause deforestation. We’ve started on palm oil but we’re now also looking at all their pulp and paper procurement. Beyond that, and in time once we’ve made progress on palm oil and pulp and paper, there’s a commitment from the company to look at the life-cycle of all their products with a view to tackling any deforestation footprints.

This really is incredibly ground-breaking and in line with TFT’s philosophy on products. Imagine if every company in the world took the same stance. If we accept that it’s product supply chains that cause deforestation and then companies push demands back down the supply chain to remove deforestation in the same way they push for lower prices, better quality, new technical specs, designs etc, then the natural innovation that’s inherent in the way that businesses work to create a competitive advantage will be focused not on getting the cheapest wood or the cheapest oil and hence leading to deforestation. The innovation will be transformative in that companies will have to ensure and more importantly prove to their buyers that their products haven’t caused deforestation.

We already have another of our TFT members—the E. Leclerc supermarket chain in France—adopting the same philosophy. We need critical mass here—If we can get the largest companies and the smallest companies to follow the Nestlé example and say “No Deforestation!!” I believe we’ll see a dramatic and immediate decrease in deforestation; much more rapidly than any global policy forum could achieve. That’s because business moves fast and millions are made and lost on the basis of products meeting buyers specs. If the specs say “No deforestation” and are truly implemented—bang, immediate impact.

Draining and clearing of peat forest in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Beyond this, Nestlé’s commitment to work with and financially support their supply chain partners to transform their land management practices to achieve sustainability standards is also ground-breaking. It’s very much in line with Nestlé’s approach with other products but also what is unique about TFT. Our members don’t depend on aid funds to make their products responsible. They take responsibility themselves and invest accordingly, in the same way that they invest in new technology or in a new innovation to improve their competitiveness in the market.

Lastly, Nestlé’s Responsible Sourcing Guidelines (RSGs) are ground-breaking in that they commit to not only looking at High Conservation Value Forest (HCVF) and peat and protecting high carbon forest—all ground-breaking in themselves—but most importantly they enshrine the concept of Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) thus pushing suppliers to consider the rights and voice of indigenous and local communities in their land management practices e.g. at plantation establishment. This means that if you’re establishing a palm oil plantation today and you hope to supply Nestlé in the future, you had better engage in a credible process to deliver FPIC now. Imagine the immediate shift in plantation establishment practices from tomorrow on if every company took this approach.

Mongabay: How will you conduct audits of Nestle’s palm oil sources? What will you be looking for?

Scott Poynton: Our field teams are now meeting with Nestlé suppliers. We have Nestlé’s Responsible Sourcing Guidelines (RSGs) and we’ll be looking for practices that meet the RSGs and those that contravene them. We don’t see ourselves as auditors really; yes, there’ll be audits but they’re more gap assessments conducted with a view to identifying where performance isn’t in line with the RSGs and then preparing an Action Plan to help the company become compliant.

Mongabay: What activities will get a company banned from supplying Nestle?

Scott Poynton: Nestlé prefers not to speak about banning suppliers. Rather, they speak about suspending someone from their supplier list. If a company is found to be in contravention of the RSGs and then shows no willingness, but more importantly, no action on the ground to change practices then they will be suspended until such time that they can prove their compliance with the RSGs. If a company doesn’t meet the RSGs but works hard with real on-ground change to become compliant, then Nestlé will continue to do business with them.

Mongabay: Do you think your work with Nestle will bring other palm oil users to you?

Scott Poynton: Yes, I believe so. It may take time and people will perhaps wait to see the results but I’m certain that we’ll see more interest in our work. We’re already in discussion with some palm oil growers about a stronger form of engagement beyond our partnership with Nestlé.

Mongabay: Nestle uses a very tiny portion of the world’s palm oil supply. How hopeful are you that other palm oil uses, especially the big markets in Asia, will move to use only sustainable sources?

The orangutan has become the symbol of the protest against unsustainable palm oil. The Sumatran orangutan, pictured here, is Critically Endangered, largely due to habitat loss. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Scott Poynton: Well, I’m hugely hopeful. As I’ve mentioned, our whole philosophy and working model is predicated on one end of the supply chain taking responsibility for what happens at the other. If big markets around the world but also in Asia understand that chopping forests down is not such a good thing and then follow the Nestlé lead of saying “No deforestation in our products please” then we really can make a huge impact. We could change not only the palm oil product story, but the whole story surrounding global deforestation. I believe we’re poised at a very critical tipping point.

Mongabay: Facebook, Twitter, and other social network sites were key in pushing Nestle. Do you think this is the new face of environmental activism?

Scott Poynton: I think it certainly has an important role to play—very important. But these alone are not enough. These were very powerful in the Greenpeace campaign against Nestlé because Greenpeace had such powerful, well-verified evidence linking Nestlé with poor practice in the field. With that, the social media became powerful; had Greenpeace not done their homework, it would’ve shone through and the campaign would not have gotten off the ground. Environmental activists need to stay close to their roots, to the ground in fact; don’t just rant on Facebook or Twitter and expect a similar result to that achieved by Greenpeace with Nestlé. Build up the compelling evidence first then use social media to broadcast the information.

CHINA

Mongabay: Recently The Forest Trust worked with a number of groups to produce the first 100 percent legal Chinese plywood manufacturer. What is important about this achievement?

A Chinese firms converts an old-growth forest into a rubber plantation in Northern Laos in January 2009. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Scott Poynton: I’m glad that you’re interested in this because the story didn’t really get picked up by the press. We think it’s hugely important because everyone looks to China as the bogeyman—we can’t save forests because the Chinese industry are devouring them to supply global markets. And yet here’s an example—OK, only one and we accept not yet an indication of an industry transformation—of a Chinese company responding to and working with not only their customer but also their suppliers to solve legality issues in their supply chains—both up and down the supply chain. Chinese factories typically buy wood from traders, on the open market and with no traceability.

Our Chinese factory partner instead engaged directly with one of our forest project partners and bought face and back veneers directly from them. They also engaged directly with farmers growing Poplar for core material. It represents a far more responsible way of doing business and that’s significant I think. It’s more complex, takes longer and thus is more laborious but we’ve shown that it’s achievable. The key now is that our UK partner and the Chinese factory get orders for this product and push more demand back down the supply chain. If that happens, the much needed transformation could gain traction.

The other thing that’s important about this achievement is that it was for a composite wood product. Again, I accept that plywood is not as complex as MDF but it’s composite nonetheless and one of the complaints against the Lacey Act from industry is that composite products are nigh on impossible to control. We just proved otherwise and it’s given us the impetus to start looking at how we can sort out MDF. We’ve embarked on that with some of our members. It’s more complex for sure, but by going right back to first principles, I believe we can do it. Our work is transformative; if you want Business as Usual, don’t work with TFT. But if you want to get deforestation out of your products, this Chinese achievement shows it’s possible.

Mongabay: How will the certification help the Chinese manufacturer?

Scott Poynton: We very much hope it will secure them new business. At TFT we say “Good Wood, Good Business” and our hope is that everyone in a Responsible Product supply chain makes more money by being responsible than they did before. Indications so far are positive. Our UK partner is receiving serious interest in the product—the first shipment is on the water bound for the UK now—and this will hopefully translate to increased business for this legal product line. That will push orders back down the supply chain to the forest which will get more return on their operations which in turn will fund their push to FSC certification.

Mongabay: Given your recent success in China, do you see a way to encourage Chinese companies to abide by the country’s guidelines for overseas forestry?

Scott Poynton: Chinese businesses are no different from businesses elsewhere—their primary objective is profit and at TFT we’re comfortable with that. If delivering Responsible Products is more profitable than delivering illegal ones, then Chinese companies (and all other companies the world over) will be happy to abide by any guidelines. The tipping point in this case depends on whether UK customers buy this legally verified plywood. If they don’t, the industry will deem the whole achievement a waste of money and the guidelines will go out the window. If they do, and you can be sure the broader industry in China is watching, then we’ll see the transformation we all hope for.

FORESTS

Mongabay: Is it possible to save the world’s forests and still meet the increasingly high demand for forestry products worldwide? In other words, is it time to address the issue of overconsumption?

Click to enlarge |

Scott Poynton: It really is time to address overconsumption but doing so is not easy; there’s no switch to flick. We’ve challenged ourselves on this and—rightly or wrongly—see the whole process as something of a journey. There are many people who get the overconsumption issue now and are careful in their purchases. Yet the majority are not and so getting Responsible Products into supply chains is a challenge. If more companies take the Nestlé and E. Leclerc approach, we can quickly embed “No Deforestation” in product supply chains regardless of whether consumers demand it or not. The No Deforestation story will slowly get out there and more and more consumers will value it and it will be a competitive advantage for Nestlé, E. Leclerc and any other company that engages. In time, others will follow because they’ll be losing market share and so slowly we’ll see a transformation. I believe that this will happen. Somewhere along that transformative journey, leading businesses will identify the next competitive advantage and at some point, as they perceive their customers are asking for it, overconsumption will come to the fore. That is, nailing overconsumption in your business model will give you competitive advantage. It’s some way off but not as far as some believe. For it to work, there has to be a competitive advantage in delivering it. When your profitability depends on turnover growth which is driven by consumption…yes, it’s a dilemma. But I have faith in leading businesses to work through the thinking on this; we’re not there yet, but bright minds are already focused on it. Future generations of bright young leaders have a responsibility here to shape a new business model.

Having said that, I still believe that even with today’s consumption levels, with a “No Deforestation” philosophy, we can already make huge and rapid strides with significant impacts against deforestation. We don’t have to wait for a new business model; we can have an impact now. We’ll still lose forests, but our target must be to lose as few as possible. Every hectare counts and if we can save a single hectare based on a “No Deforestation” philosophy, we’ve done something positive. We can do it, I think.

Mongabay: What do you see as the potential impact of the Lacey Act and FLEGT in getting companies to more responsibly source their forest and agriculture products?

Scott Poynton: The potential impact is huge; whether it is ever realized will depend on how effectively the Lacey Act and FLEGT regulations are enforced. We do need prosecutions to prove that there are teeth there. No enforcement means the industry will not take the risk seriously and will work the loopholes. I don’t believe the Lacey Act or FLEGT will have any impact on responsibly sourced agriculture products but a similar approach, with simple, elegant legislation, could. Legislation that made it illegal to trade in any product linked with illegal deforestation e.g. a food product containing palm oil, soy or beef from plantations, farms or ranches created by illegal forest clearance would be extremely powerful—so long as it had teeth. My view is that we don’t need REDD and we don’t need Copenhagen type meetings—whilst everyone is wringing their hands over REDD, REDD+ our forests continue to go up in smoke. What we need is a global economy that demands “No Deforestation” in the products it uses and that enshrines the key elements of the Nestlé RSGs—High Conservation Value Forests, high carbon value forests, peat, laws, FPIC. Then we can set about saving forests—today.

Mongabay: Your group works closely with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). How do you respond to criticism of the FSC for certifying old-growth forests and monoculture plantations as ‘sustainable’ forestry?

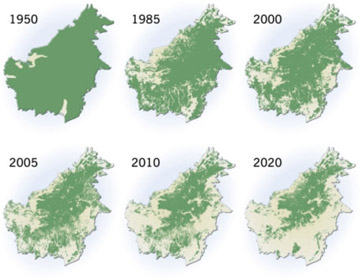

Figure 1: Extent of Deforestation in Borneo 1950-2005, Projection to 2020. The island of Borneo is split between Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei. |

Scott Poynton: We could spend a lot of time and energy arguing about whether FSC certification represents sustainable forestry. TFT takes a pragmatic view here; our forests are disappearing before our eyes and so we have to do whatever we can to protect them. I support the whole concept of protecting Intact Forest Landscapes where they still exist—no logging is better than FSC certified logging if the forests can be protected—but I also spend a lot of time out and about in the real world and I see that the folk that control land use, i.e. governments, don’t necessarily see it the same way. Let’s spend time working with governments to see what can be done to set as many forests aside in protected areas as possible—YES—but let’s also get it that National Parks don’t necessarily represent a safe haven for our forests. Governments want to make money out of their natural resources so I understand why we see so few protected areas and then why these are often poorly protected.

Stopping people illegally logging protected areas comes back to having strong regulations like Lacey and FLEGT but also having companies pushing “No Deforestation” with robust systems in place to enforce it. But most of our forests are NOT in protected areas and never will be so where decisions have already been taken to zone a forest for production, then my view is that we should ensure that whatever operations occur there are ‘responsible’. I use that word deliberately because responsible forest management for me means that before any operations appropriate planning has been done to minimize the impact, that indigenous and local communities have been engaged in a credible and respectful process to deliver FPIC, and that HCVF values are protected. After any operations, the forest should still be functioning ecologically as a forest with limited and certainly no long-term diminution of its conservation attributes and with indigenous and local communities satisfied that their rights and resources have been respected and are intact. In that context, and if done well, FSC certification can help deliver this. I don’t say that it always gets it right, but it certainly helps us down that path, so for me it is a useful tool; indeed a very useful tool if people then buy the FSC certified products, to conserve forests. Perhaps not in their natural, pristine state, but the human hand touches every cm2 of our global landscape and I believe that if we can make that touch as light as possible, then whilst we will see change, we’ll still have forests. Altered forests, but forests nonetheless.

Palm oil plantation in Sumatra. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Likewise for monoculture plantations—if these can relieve pressure on natural forest ecosystems, and I agree, there’s a large unfinished debate on whether they can do this—and if they’re managed in a way that enhances the livelihoods of indigenous and local communities and protects biodiversity, then I can live with it. I do have real concerns about some of the FSC certifications of large scale plantations, particularly in Brazil. There seems to have been a breakdown in good process there with poor social and environmental outcomes as a result. For me, FSC certification isn’t a Holy Grail. FSC provides guiding principles of responsible forest management and then it’s up to us to ensure that the operations we’re working with adhere to and far exceed them. It doesn’t matter for me whether the operations are natural forests or plantations; just that the standard is properly implemented and that people and the environment benefit as a result. I haven’t visited the controversial certifications in Brazil but it does seem that there are real concerns there from local communities. NGOs that I respect very much—like FERN—tell me that the concerns are real and justified. I have a real sympathy with that and would like to see the FSC take a more active approach to resolving these complaints. I love the FSC standard; I’m just not always satisfied with the way the FSC system works to implement it.

Mongabay: Finally, as a forester what is your idea of sustainable forestry?

Scott Poynton: I think I’ve answered that in the question above but to reiterate, I prefer to speak of responsible forestry—forestry that respects the environment and enhances peoples’ lives. Bottom line, responsible forestry leaves forests standing and functioning ecologically as forests, delivering benefits to people and sustaining our rich endowment of plant and animal biodiversity.

Related articles

A new world?: Social media protest against Nestle may have longstanding ramifications

(03/20/2010) The online protest over Nestle’s use of palm oil linked to deforestation in Indonesia continues unabated over the weekend. One only needed to check-in on the Nestle’s Facebook fan page to see that anger and frustration over the company’s palm oil sourcing policies, as well as its attempts to censor a Greenpeace video (and comments online), has sparked a social media protest that is noteworthy for its vehemence, its length, and its bringing to light the issue of palm oil and deforestation to a broader public.

Nestle’s palm oil debacle highlights current limitations of certification scheme

(03/26/2010) Last week Nestle, the world’s largest food processor, was caught in a firestorm when it attempted to censor a Greenpeace campaign that targeted its use of palm oil sourced from a supplier accused of environmentally-damaging practices. The incident brought the increasingly raucous debate over palm oil into the spotlight and renewed questions over an industry-backed certification scheme that aims to improve the crop’s environmental performance.

Nestle caves to activist pressure on palm oil

(05/17/2010) After a two month campaign against Nestle for its use of palm oil linked to rainforest destruction spearheaded by Greenpeace, the food giant has given in to activists’ demands. The Swiss-based company announced today in Malaysia that it will partner with the Forest Trust, an international non-profit organization, to rid its supply chain of any sources involved in the destruction of rainforests. “Nestle’s actions will focus on the systematic identification and exclusion of companies owning or managing high risk plantations or farms linked to deforestation,” a press release from the company reads, adding that “Nestle wants to ensure that its products have no deforestation footprint.”

How Greenpeace changes big business

(07/22/2010) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation. A prime example of this power is evident in a string of successful Greenpeace campaigns, which have targeted some of the largest drivers of deforestation, including the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia and the soy and cattle industries in the Brazilian Amazon. The campaigns have shared a common approach: target large, conspicuous consumer-facing companies that sell in western markets.

Compliance with national law not enough to meet int’l market demands

(10/05/2010) A UK-based cosmetics firm is severing ties with its palm oil supplier after a story in The Observer reported the Colombia-based company sought the eviction of peasant farmer families to develop a new oil palm plantation, reports the Guardian.

Eco-friendly palm oil initiative censures company linked to deforestation

(09/23/2010) The Roundtable On Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a body the sets standards for eco-friendly palm oil production, on Thursday said Indonesian palm oil producer Sinar Mas Agro Resources and Technology (SMART) breached its sustainability criteria and faces expulsion, reports AFP.

Another food goliath falls to palm oil campaign

(09/22/2010) One of the world’s biggest food makers, General Mills, has pledged to source only sustainable and responsible palm oil within five years time. With this announcement, General Mills becomes only the most recent food giant to pledge to move away from problematic sources of palm oil, which is used in everything from processed foods to health and beauty products. Nestle made a similar pledge earlier this year after a brutalizing social media campaign that lasted for months while Unilever, the world’s biggest palm oil buyer, has been working closely with green groups for years.

80% of tropical agricultural expansion between 1980-2000 came at expense of forests

(09/02/2010) More than 80 percent of agricultural expansion in the tropics between 1980 and 2000 came at the expense of forests, reports research published last week in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The study, based on analysis satellite images collected by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and led by Holly Gibbs of Stanford University, found that 55 percent of new agricultural land came at the expense of intact forests, while 28 percent came from disturbed forests. Another six percent came from shrub lands.

Burger King drops palm oil supplier linked to Borneo rainforest destruction

(09/02/2010) Burger King announced it would no longer source palm oil from Sinar Mas, an Indonesian conglomerate, after an independent audit showed one of the company’s subsidiaries had destroyed rainforests and carbon-dense peatlands in Borneo and Sumatra, according to a statement on the fast food chain’s Facebook page.

Rapid growth of palm oil industry tramples indigenous peoples’ rights, says report

(08/30/2010) Rapid expansion of oil palm plantations across Southeast Asia have run roughshod over customary tenure systems, resulting in exploitation of local communities, conflict, and outright human rights abuses, reports a new assessment of the palm oil sector by the Forest Peoples Programme (FPP), an international indigenous rights group.

(08/19/2010) Sinar Mas, an Indonesian conglomerate whose holdings include Asia Pulp and Paper, a paper products brand, and PT Smart, a palm oil producer, was sharply rebuked Wednesday over a recent report where it claimed not to have engaged in destruction of forests and peatlands. At least one of its companies, Golden Agri Resources, may now face an investigation for deliberately misleading shareholders in its corporate filings.