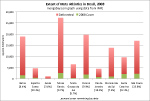

Sustainable development seems to have left the realms of institutional debate in Brazil and has emerged into a reality for businesses to remain competitive in their markets.

It is also being used as a tool to stimulate the country’s economic growth.

A notable example of this is hydroelectricity, as the country has strived for many years to generate electricity in innovative ways, rather than relying on the use of fossil fuels. Companies are also voluntarily signing up and engaging in Brazil’s GHG Protocol Program with a view to reduce carbon emissions and businesses large and small are leading on sustainable business practices.

While Brazil has received a lot of respect for this forward thinking approach to sustainability, they have also been heavily criticized for hydro projects since the 1980s; in recent months the target has notably been the decision to move forward with the plan to build 3 dams on the Xingu River, which lies in the Amazon Basin.

The most infamous now and the principle one, ‘Belo Monte’, will continue Brazil’s provision of hydroelectric energy, but will also potentially turn tributaries of the world’s largest river into ‘an endless series of stagnant reservoirs’, explains the new short film released by Amazon Watch and International Rivers, narrated by Sigourney Weaver. The film is made via a Google Earth 3-D tour and reveals the potential impact of the dam, as well as the consequences for the indigenous peoples in the area.

“Their way of life will disappear,” said the actress.

Hydroelectricity provides 80 per cent of the power that Brazil generates and Belo Monte will generate a further 11,000 MW and will be the third largest dam in the world, adding almost 20 per cent to Brazil’s electric power capacity. Indigenous tribes, as well as environmentalists, have protested strongly against the project for over 30 years. Belo Monte’s reservoirs threaten to flood 668 square kilometers, push more than 20,000 people out of their homes and reduce the flow of the Xingu to merely a trickle during parts of the year. Water supplies will be put at risk; endangering people and animal species, as fish migrations will be blocked causing devastating consequences for the local fisheries that depend on the river for their subsistence and the aquatic creatures within the river that depend on it for the survival of their species.

The Balbina dam flooded some 2,400 square kilometers (920 square miles) of rainforest when it was completed. |

It is difficult to comprehend how unrest around such a massive project could be disregarded, enough so that the project has been allowed to proceed to this stage, for such a long stretch of time. As far back as 1989, a Kayapó woman warrior held her machete to the face of José Antônio Muniz Lopes, who was the president of the state electricity company that holds the contract today, Eletrobrás. Her drastic measures were emphasis of the indigenous tribes’ fear around the dam being built and those fears have continued and have grown to this day and are now supported by many environmental organizations, as well as the Brazilian people.

It is hard to imagine the extent of the damage building the dam will do when you haven’t stood yourself in the Amazon and seen her beauty and magnitude and seen how the people and the animals live interdependent with her forest’s lush green; words fail to encapsulate it also. Thousands of tiny and large rivers run through the forest and water is a major part of the ecosystem itself which is why if the Belo Monte project is undertaken, it will be a disaster. Building this series of dams is considered to be a key turning point for the Amazon and not in a positive way – it will be the end of life as they know it now for the thousands of people and species living there and the beginning of many more projects like Belo Monte as Brazil tries to meet the energy demands of its country in an economic way. The flooding of the forest to accommodate the dam will provoke a massive release of methane from the vegetation rotting beneath it, millions of years worth of a stored greenhouse gas 25 times more potent thanCO2 and the risk of malaria in surrounding areas will increase also as the insects are attracted to the stagnant water. If past experience of dam projects in the Amazon is any model, Belo Monte will give local people no other choice but to join the many loggers already active in the Amazon, as they can no longer earn income from fishing or their traditional livelihoods like hunting, which will contribute to further large-scale devastating deforestation.

This development cannot be considered sustainable if you add to this the introduction of electricity grids, transmission lines and access roads that will put further pressure on this precious rainforest.

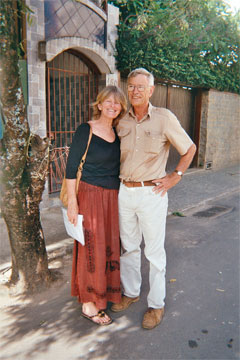

Robin Le Breton and Binka Le Breton |

The Amazon’s lesser known sister forest, the Atlantic has already suffered similar destruction, caused by human development, in fact there is only 7% of this precious forest left. In spite of this, it is one of the five richest forests in the world as well as being one of the most highly threatened. What makes the Atlantic forest so special is its biodiversity – in terms of plants and birds and animals, especially primates and amphibians. It is distinguished from many other forests by the high levels of endemicity – species that are only here, and nowhere else. It has maybe 20,000 plant species of which about 6,000 are endemic, for example, of the Atlantic forest’s 25 primate species, 20 are endemic and 14 threatened with extinction. As for its struggle for existence, it didn’t really become a cause until about 30 years ago, long after people had been expressing concern about the destruction of the Amazon. Many people simply didn’t see it, because it didn’t feature in the news: there was not a lot of research on what it holds, even now, and around it being the biggest center of population in Brazil – nearly all of its people live in the Atlantic Forest. Two people in particular are battling hard for its survival.

Robin Le Breton and his wife, Binka, are well accustomed with the notion of ‘sustainable development’. They are Directors of a Research Center in a little town called Rosário da Limeira, in the south-east of the state of Minas Gerais.

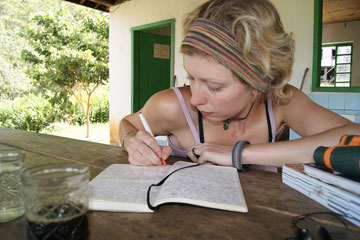

I spent a month working with Robin and Binka in January this year, within the beautiful Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest, known locally as the Mata Atlântica and every day since my thoughts around the subject of what can be considered sustainable have dramatically changed. The environment in which they live is typical of many others throughout this breathtaking forest, degraded through the development of agriculture to meet the country and the world’s needs for coffee, amongst other things.

Their research focuses on two things: sustainable land management technology to ensure the future of this forest and its people and the development of alternative products from the forest’s land that can generate income for them and provide an incentive for forest conservation in Brazil.

Clare Raybould, the author, in Iracambi |

The Belo Monte dam does not directly impact upon the Atlantic rainforest, but the whole subject does give rise to questions regarding the sustainability of this form of generating electricity and I wanted to know what this incredible couple, who have devoted the last 10 years of their life working to protect what is left of the Atlantic think about hydroelectricity.

Do they feel that it is sustainable? Or, is it an example of a positive idea born out of needing to do things in a different way, which hasn’t been thought through thoroughly enough. Or are there wider implications, considering the project is being driven by the Brazilian Government.

I also wanted to know what he thought the impact of climate change would be upon the long term future of the dams, considering our unpredictable climate and the predicted population rise anticipated for the years to come. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has predicted a devastating range of impacts from climate change upon Brazil, including an increase in the intensity and number of extreme weather events. The region’s huge geographical diversity means that patterns of vulnerability to climate change are extremely varied, which admittedly also makes modeling difficult, but the possibility of less rain can’t be ruled out and would affect Brazil’s capability to generate electricity via hydropower and would also impact supplies of drinking water compared with demand. Will all the destruction planned for the short-term prove to be a waste in the long-term?

An Interview with Robin and Binka Le Breton:

Mongabay: Robin, on your website you describe yourself as a Consultant on Natural Resource Management, what does this mean?

Robin: Consultants, in order to be hired, have to give themselves fancy titles, like “Public Transport Collective Vehicle Operator”, which means a bus driver. Management of natural resources is what a farmer does when he decides to put this cow into that field or plough up this field to plant corn. So it’s a fancy term for a farmer. But farmers also learn about other types of land use – such as maintaining a forest instead of cutting it down – so the term includes these aspects as well, which the layman might not understand from the simple term “farmer”.

Mongabay: How does Iracambi fit into this role?

Robin: It is the name of our non profit organization, Amigos de Iracambi, supporting a Research Center which is based on a sustainable forest farm where we can put our ideas to work. We’re in the buffer zone of the Serra do Brigadeiro State Park in the mountains of the state of Minas Gerais in southeastern Brazil. It’s an area of extraordinary beauty, abundant water and exceptional biodiversity.

Mongabay: Binka, what is your role in this partnership and can you tell me a about Iracambi?

Binka:My role in this partnership is spokesperson for Iracambi, for the Atlantic Forest and for the issues of environmental and human rights that we face daily. My frequent travels to the USA give me a platform for this, the opportunity to visit universities and recruit students to work with us, as well as catching up with thinking from the northern perspective. This, in turn, allows me to interpret northern thinking to our everyday realities in Brazil. I’m also the president of the NGO and I write books on environmental and human rights. My most recent communications job for Iracambi was working with a wonderful team on completely revamping our website (http://www.iracambi.com/english/forestfutures.shtml) I hope you like it!

Mongabay: How is land used around Iracambi, and how is that land use changing?

Coffee plantation. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Binka:It has been the custom in Brazil ever since the European first came here to use the land until it is exhausted and then move somewhere else. Farmers invest the minimum they can in the land: they’ll go on using it until it won’t produce any more, and then abandon it. An Indian Farmer, whose family has farmed the same land for generations, would never do that as he knows that if he does, his children and grandchildren won’t be able to live off the farm. Here however, without that experience and the European custom not changing, we are running out of new land to plough up and new forests to cut down and have lots of land that is bring farmed to exhaustion because there is no place to move to.,

Mongabay: Brazil as a nation has been considered as forward thinking regarding sustainability. How does this tally with the negative implications of Belo Monte dam?

Robin: I can’t imagine where that idea came from: Brazil has never been forward thinking about anything – it is not part of our culture. President Lula had to create a Ministry of Long Term Planning as there has ever been any long term planning by Government. He had to get someone to come all the way from Harvard University to be the Minister since he couldn’t find anyone around here who knew what long term planning was, but after about a year, when it was clear to him that no one had any idea what he was talking about, the Minister quit and went back to Harvard. This is true; I’m not making it up.

Mongabay: Can you tell me anything about Brazil’s Accelerated Growth Program and how this will drive the direction of energy supply in the future?

The view from Iracambi’s kitchen. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Robin: The PAC (Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento – the Brazilian name for the Accelerated Growth Program) is more about getting Dilma Rousseff elected than developing Brazil, and from that angle it looks pretty successful, too. Certainly, many of the projects in it are overdue, so I don’t mean to say that the projects are necessarily bad, in fact many of them have been waiting for years to be carried out.

How will it drive energy supply: well, whatever Brazil does it is going to need more energy – because of our failure to invest in energy projects during the 1980s and early 1990s, we have a very tight supply situation. Accelerated industrial development (which we need) will make it even tighter, no doubt about that. Whether Belo Monte is the right solution is another question, though.

Mongabay: I described Brazil as forward-thinking because there has been some really positive media attention focussed on Brazil in the UK, part of the reason I chose the country for my own research – I wanted to know what can we learn as a nation, especially as we are suffering our own recession and should still be looking to improve environmentally. However, as I described in the introduction, certainly that positivity has turned to scrutiny in recent months – the oil industry has raised questions about Brazil’s intentions and now the Belo Monte dam is receiving extensive criticism also, do you think in some way this was predictable? It is a huge leap back from the image that was being presented through the forward-thinking architecture we saw in articles and news reports and opposes the innovative energy policies that were being held as those we should follow in our own nations…

Robin: Of course – this debate has been going on for over 20 years and the environmentalists have always opposed it, perhaps you just don’t read enough about that.

Where farm and forest meet – Iracambi’s mantra – farmed land where forest used to be. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

The project is being presented in a misleading way now also. It is being presented as though the plan is ONLY to build Belo Monte. Technically, it doesn’t makes sense to build the Belo Monte dam if you are not going to build the other dams in the system – it’s the other dams that are going to keep Belo Monte operating – that’s the whole point. Belo Monte by itself would only produce 1,400 MW – it’s only when you build the other dams that you can reach 11,000 MW. But the ecological consequences on the Xingu river will be catastrophic

Mongabay: So do you see hydroelectricity as a sustainable form of energy for Brazil moving forward?

Robin: Clare, the issue of Belo Monte and the issue of hydro-electric power are different. Brazil needs power and still has some potential to develop more hydro power, as well as other forms of green energy and – this is important – the potential to make better use of what it has.

But Belo Monte is not a good project. We need energy, but we don’t need bad projects.

Mongabay: So you are not necessarily against large hydro-electric dams as a form of green energy?

Robin: No, but they do tend to create large problems. Usually these are caused by incomplete planning: the Itaipú dam, for example, will have its operating life much reduced because those concerned “forgot” to take measures to stop farmers ploughing up land on the banks of the dam and causing it to silt up. Obvious, you’d say, but nobody did anything about it until it was too late – why not? Because of too many conflicting interests at stake.

The Nursery where the seedlings are planted, ready for reforestation. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Big project = big problems.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t follow that small dams are necessarily a solution either. Minas Gerais is the state in Brazil with the most potential for building small dams, because of the mountains, but there are plenty of problems associated with them, too.

Mongabay: What in your opinion are alternative options to dams?

Robin: That is the problem: they are still the best option, for Brazil.

Mongabay: OK, what about climate change – is extreme weather already a

problem for the people of the Atlantic rainforest and do you see this as a consequence of climate change?

Robin: Undoubtedly. The problem really is that we just don’t know what will happen, but an already severely damaged environment has a hard time with extreme weather events,

Mongabay: Do you have specific thoughts around climate change and the future of the hydroelectric energy?

Robin: In 2006 and in 2007, we had dams bursting here because of heavy rain they hadn’t been built to stand. We hope that dams being built now will take into account extreme future events – it is in the design criteria to build for the millennium extreme, but what about the dams that were built 20 or 30 years ago when nobody thought too much about extreme weather?

Mongabay: Have dams directly affected the Atlantic Forest in the past and is it a concern for the future?

Robin: There have been cases – Barra Grande, in the State of Santa Catarina is one. It exterminated endemic plant species and flooded a large area of threatened forest because the Environmental Impact Statement was a lie, but by the time anyone discovered that, the dam had already been built. But I think the danger for the Atlantic Rainforest from dams is much less than in the Amazon as most of the best sites have already been occupied.

Mongabay: Already occupied by what? What has been the main cause of destruction in the Atlantic forest and how does it compare to the destruction of the Amazon?

Iracambi lies peacefully hidden in the trees. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Robin: The destruction of the Atlantic Rainforest began in 1500 and has been going on ever since by virtue of the fact that it’s where most people in Brazil live and where most of our industry is based. In both forests, the process began with large areas of forest being cleared for agriculture, but in the Atlantic Rainforest it didn’t stop there. In the Amazon, there won’t be the pressure from urban and industrial development. But I don’t think that makes much difference: once the forest has gone, it’s gone – why it went isn’t going to alter that.

Mongabay: What do you mean by urban and industrial development? Surely, in years gone by when the Atlantic forest was still there, the people used it to survive?

Robin: Of course, but nobody has ever lived sustainably in the Atlantic Rainforest since the white man came. Even then people only survived by chopping it down, since no one ever thought about sustainability. We chopped down the indigenous people, too, so we don’t know much about how they lived. Coffee, one of the pillars of Brazilian economy until as late as the 1970s, was a disaster for the Atlantic Rainforest ever since it was introduced in the eighteen century.

Urban and industrial development has happened – the people spilled out of the cities into the forests and technology has advanced – in general I don’t believe that we should be Luddites about it. If people decide that it’s more fun to go and live back in the city – as they inevitably will – we shouldn’t try and put obstacles in their way, even if we feel it may not be in their best interests or the interests of the environment.

Mongabay: But you have done a lot of work with the rural communities living within the Atlantic Rainforest to change their views about the environment and how its conservation can be positive for their future; I saw the benefits of that first-hand myself. You have worked very closely with them to implement the practical solutions you are finding from the research you do, so what are your thoughts on the impact building of yet another dam will have on the rural people after you have taught them so much about technology that positively affects the environment and their lives? Do you worry that it might make them feel conservation management technology is not as profitable as building a dam and clearing the rainforest to do so?

Forest Fragments. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Robin: Well, thankfully Belo Monte itself doesn’t pose any threat to us here, but we do face a similar threat from bauxite mining. It’s essentially the same issue. Powerful commercial interests wanting to use natural resources, supposedly, to bring “development” to Brazil. The politicians see it as creating employment, generating tax revenues and all other kinds of benefits which it may indeed bring – but historically the impact on the local people is much less beneficial.

Mongabay: Elaborate…

Robin: Brazil has changed so much in the last 1o years that it’s hard to tell what is cause and what is effect. For agriculture in particular, things have got worse, as they have in agriculture all over the world. But in Brazil, living standards in the rural areas have improved enormously even despite the increasingly difficult economic situation farmers face. Better public services and better access to consumer goods have a lot to do with the change. What directly affects Iracambi most, working as we do on conservation issues, has been the huge increase in awareness of environmental issues. Of course, we would like to say that we have contributed to this – and I believe we have- but it would be merely boastful to say it was all our dong. We have a long way to go, but there are grounds for optimism.

Mongabay: Robin, how much of the Atlantic Forest is left?

Robin: 7%

Mongabay: What are your fears for the Atlantic rainforest moving forward?

Forest Fragments. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Robin: There is a growing impatience in the business sector – especially those involved in infrastructure projects. In the Presidency of the Republic this specifically relates to environmental protection – it is their belief that it is holding up the development of the country and this is a real threat to the environment. We are not immune to these pressures any more that any other country – build more runways at Heathrow, drill for more oil in the Gulf of Mexico, etc. For example, there is a very dynamic and far sighted Brazilian investor in the mining business, Mr Batista, who typifies the environmentalist’s as Public Enemy Number One. He’s just doing his thing – making money out of using natural resources, and he happens to be very good at it, but every time he starts a new project, the whole environmentalist army rises up against him – no wonder he considers us all a bunch of screaming rabble. As I touched upon, in our area, the big development is the bauxite mining, and the issue of the threat to the environment is the same at al Belo Monte. We all know we need bauxite (for aluminium) but we don’t want anyone digging it out here. NIMBY, to use the neat expression you have over there.

Mongabay: Brazil’s forestry code has been described as one of the most progressive in the world. The government has established a zero deforestation target by 2010 for the Atlantic Forest and has pledged to establish protected areas covering at least 10% of the forest, which they have made progress towards doing this year, what is going on?

Robin: Well first of all I do not at all agree that our forestry code is one of the most progressive in the world and that’s exactly what the furious debate is about – it’s an extremely unprogessive law. But let’s leave that discussion for another time.

Mongabay: Ok, well how about the fact that like the mining industry, the Belo Monte project is backed by powerful interests and the mining industry is also driving the construction of Belo Monte, as it will supply electricity for new mines in the Amazon. The World Bank is pouring $11bn into a further 211 hydropower projects worldwide. Is business more powerful than politics?

Hacked down forest, ready for agriculture. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Robin: Now, you have got to the real nub of the matter, the conflict is just the same as everywhere else: everybody wants to consume more, but to provide for these consumption habits we have to digger deeper and deeper in to our natural resource base. If you look at the World Resources Institute site, you‘ll see the numbers – how much water it takes feed a steer to produce a kilo of beef: how much steel you need to build a car. Then do the math of how much of each you’ll need if every Chinese is to have the level of consumption that the average Englishwoman has (which is what they want – make no mistake about that) and you can see where we are heading. You can’t blame Mr Batista, the Brazilian minerals king for trying to cash in on this, nor the electricity company that wants to build Belo Monte – they’re just doing their thing. The World Bank is doing its thing too: it lends money to governments to develop their countries. If the counties decide that the way they’re going to do that is by digging out all their natural resources, that’s the way they’re going to do it. Either the World Bank lends them the money or it shuts up its shop – that’s what it exists for. Of course it is unsustainable. Many people realize that, but they hope that they can get catch the good life now and by the time their kids have grown up maybe someone will have come up with a brilliant idea of how to get more out of less. Maybe they will – but what if they don’t?

Mongabay: So, what needs to change to ensure the protection of Brazil’s remaining forest, both in the Amazon and the Atlantic; what do you think is blocking change?

Robin: The law is not the problem. Changing the law or making new laws is not going to change anything. In Brazil we have more laws per inhabitant than any other planet in the universe (I just made that statistic up – but it won’t be that far off the truth) as well as a good number of the stupidest laws in the universe, too. The change will come when people want it to – that’s the way it always works. So, when people decide that they’ve finally cut done enough of the Amazon, they’ll stop doing it. Whether by that time there’ll be anything left to cut down, I couldn’t say – though since I am an eternal optimist, I believe there will be.

Mongabay: Tell me about the Atlantic Rainforest, its beauty, its species, its importance and its struggle compared to its more famous sister …

Robin: We already mentioned that only seven percent of it is left – as the Brazilian poet Carlos Andrade put it, of the hundred trees that once stood in the forest, the executioner has already despatched ninety. What makes the Atlantic forest so special is its biodiversity – in terms of plants and birds and animals, especially primates and amphibians. It is distinguished from many other forests by the high levels of endemicity – species that are only here, and nowhere else. It has maybe 20,000 plant species of which about 6,000 are endemic, for example, of the Atlantic forest’s 25 primate species, 20 are endemic and 14 threatened with extinction. The Atlantic Forest is one of the five richest in the world as well as being one of the most highly threatened. As for its struggle for existence, it didn’t really become a cause until about 30 years ago, long after people had been expressing concern about the destruction of the Amazon. Many people simply didn’t see it, because it didn’t feature in the news: there was not a lot of research on what it holds, even now, and around it being the biggest center of population in Brazil – nearly all of its people live in the Atlantic Forest. However, by the way, the forest is so badly fragmented that that many people don’t even recognize it as a forest.

Mongabay: Without NGOs like Iracambi who would look after the future of our rainforests? Who would consult with the local people about issues such as Belo Monte? Are there mechanisms in place to relieve their fears and guide them forward, so their futures are secure and more importantly, as they envisage them to be?

A forest fragment behind a spectacular waterfall. Photo by Clare Raybould. |

Robin: You know, in Brazil in the 1970s, there were no environmental NGOs at all and very few in the 1980s, which were times of maximum environmental destruction. There is no doubt that NGOs are important channels for environmental concerns along with an investigative press and a political system that gives space to express sectoral concerns. These didn’t exist in Brazil, either, in the 1970s and 80s. So yes, there are mechanisms in place now: they are not perfect here (or anywhere else, for that matter), but we are doing our best!

Mongabay: What support do you need to ensure you can continue doing your best, which so far has made incredible progress?

Robin: We need people like you, who are interested in these issues. The more you can go around saying to people “Hey, look what they’re doing in Brazil!” the better. But – very important – please don’t focus only on the bad things we do! If you can say “Hey, look at this really cool thing the Brazilians are doing to save their environment!” it probably has an even bigger impact on us Brazilians.

Mongabay: Well, I will definitely do my best to continue doing exactly that! Brazil has done some amazing things, which I saw firsthand during my trip there earlier this year and write about in my own research. However, it is hard to ignore that there is only 7% of the Atlantic Forest left, having spent time with you there myself, it is a painful figure to swallow and it is hard not to feel disheartened. Is this fate of the Atlantic what we can predict for her great sister, the Amazon? The same accelerated development, but taking place in a different way, to meet the demands of the human race, which we will look to resolve when it is too late? In a perfect world, what would be your vision for both precious forests and the truly sustainable ecosystem services that could provide an alternative to further destruction and what safeguards would need to be in place?

Robin: Don’t forget that 60% of Brazil’s population lives in the Atlantic Rainforest and about 80% of Brazil’s GDP is generated there, so it’s not surprising that the poor old forest got a bit knocked about. The percentage of the population living in the Amazon and of GDP generated there is much lower, so the pressure is not so great. But still, I would expect to find about only 30% of the existing Amazon forest still there in 50 years time .

In a perfect world, we’d never cut down another tree that we didn’t plant ourselves – but this is not a perfect world. We need to learn to co-exist with our forests – they need us to survive, and we need them to survive. So what we need to do – are doing – is to show everybody how this is true. The only way you can stop the forest being cut down is when you get enough people who think it’s a bad idea. We’ve still got a way to go on that one, though.

Related articles

New protected areas established in Brazil’s fragmented Atlantic Forest

(06/17/2010) Brazil has designated an additional 65,070 hectare (161,000 acres) of land to be protected in the Mata Atlantica, or Atlantic Forest. The land is split between four new protected areas and an expansion of a national park.

(09/23/2009) The Atlantic Forest may very well be the most imperiled tropical ecosystem in the world: it is estimated that seven percent (or less) of the original forest remains. Lining the coast of Brazil, what is left of the forest is largely patches and fragments that are hemmed in by metropolises and monocultures. Yet, some areas are worse than others, such as the Pernambuco Endemism Centre, a region in the northeast that has largely been ignored by scientists and conservation efforts. Here, 98 percent of the forest is gone, and 70 percent of what remains are patches measuring less than 10 hectares. Due to this fragmentation all large mammals have gone regionally extinct and the small mammals are described by Antonio Rossano Mendes Pontes, a professor and researcher at the Federal University of Pernambuco, as the ‘living dead’.

Destruction of Brazil’s most imperiled rainforest continues

(05/31/2009) More than 100,000 hectares of Brazil’s most threatened ecosystem was cleared between 2005 and 2008, reports a study by the Fundação SOS Mata Atlãntica and the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The “Atlas of Mata Atlântica Remnants”, released May 26, assessed the extent of the Mata Atlântica (Atlantic Forest) across 10 of the 17 states where the coastal rainforest occurs. It found that an 102,938 hectares were destroyed during the three year period. The annual loss of 34,121 hectares per year was 2.4 percent lower than the 34,965 ha recorded from the 2000-2005 period.

Brazil’s plan to save the Amazon rainforest

(06/02/2009) Accounting for roughly half of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2005, Brazil is the most important supply-side player when it comes to developing a climate framework that includes reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD). But Brazil’s position on REDD contrasts with proposals put forth by other tropical forest countries, including the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, a negotiating block of 15 countries. Instead of advocating a market-based approach to REDD, where credits generated from forest conservation would be traded between countries, Brazil is calling for a giant fund financed with donations from industrialized nations. Contributors would not be eligible for carbon credits that could be used to meet emission reduction obligations under a binding climate treaty.