Most of the US’s large ecosystems are but shadows of their former selves. The old-growth deciduous forests that once covered nearly all of the east and mid-west continental US are gone, reduced to a few fragmented patches that are still being lost. The tall grassy plains that once stretched further than any eye could see have been almost wholly replaced by agriculture and increasing suburbs. Habitats, from deserts to western forests, are largely carved by roads and under heavy impact from resource exploitation to invasive species. Coastal marine systems, once super abundant, have partially collapsed in many places due to overfishing, as well as pollution and development. Despite this, there are still places in the US where the ‘wild’ in wilderness remains largely true, and one of those is the Tongass temperate rainforest of Southeast Alaska.

“It is still intact. All of the species that existed at the time of European settlement in the 1700s are still here. Nothing is missing,” photography and conservationist Amy Gulick told mongabay.com.

Acclaimed nature photographer Amy Gulick trekked and paddled among the misty islands, bears, and salmon streams of Southeast Alaska to document the intricate connections within the Tongass National Forest. Photo courtesy of Amy Gulick. |

Author of the new photography book Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest, Gulick highlights the importance of salmon to the rainforest’s survival: “Salmon in the trees refers to a scientific discovery that shows a direct link between the salmon and forests of the coastal temperate rain forests of North America.

Salmon—caught by bears and birds—are carried from the coast into the rich old-growth forests where they are dispersed and their ocean-nutrients spread into the soil and the trees. Recording an ecological wonder, researchers have recently linked a variant of nitrogen in these rare forests to the ocean—with salmon acting as the connector from marine to terrestrial ecosystems.

Spanning nearly 17 million acres, the Tongass rainforest is America’s first National Forest, but more importantly it is the world’s largest intact temperate rainforest.

“Coastal temperate rain forests are extremely rare, covering just one-thousandth of the Earth’s land surface. They are rare because it takes just the right conditions for them to exist,” Gulick explains. “The Tongass contains nearly one-third of the world’s remaining old-growth coastal temperate rain forests, and the largest reserves of old-growth forests left in the United States.”

Managed by the US government, parts of the ecosystem have suffered from clear-cut logging which hit a boom in the 1960s, but have slowed since. According to Gulick, “there are still enough critical biologically productive watershed areas holding the ecological integrity of the ecosystem together.”

But that could change. “We’re on our way to carving [the Tongass rainforest] up, and without further protections it will just be a matter of time until we unravel this glorious cycle of life,” Gulick says.

Logging, handed out by the government to private companies, remains the primary threat in the Tongass. A controversial proposal (recently covered by mongabay.com) would give 85,000 acres of prime forest to indigenously-owned logging company Sealaska, however the company’s targeted lands are opposed by local community who say clear-cutting in the area would devastate their homes and livelihoods that depend on eco-tourism and the forest for subsistence hunting and fishing.

Amy Gulick’s book Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest tells the story of one of the rarest ecosystems on Earth. Gulick’s stunning photographs, together with essays from leading scientists and noted authors, portray a hopeful story of the Tongass National Forest, a place where trees grow salmon, and salmon grow trees. |

“No one is disputing that the corporation is entitled to additional lands. What is being disputed is WHICH lands will be transferred,” explains Gulick. “In the current legislation, the corporation has selected lands outside of its original selections and that is why Congressional approval is necessary. What concerns me most is what will happen to these lands. Regardless of who ‘owns’ them, we continue to view the Tongass with the old industrial mind set of resource extraction at an unsustainable rate. If this continues, then it’s just a matter of time until we break the ecosystem as we have done in so many other parts of the world.”

According to Gulick such complicated problems are deeply set in our centuries-old model of resource extraction and consumption.

“Overall, I feel that the single biggest threat is that of an old industrial mind set—one of looking at a place rich in resources and asking ‘How much can we take?’ Instead, we should view the Tongass as a thriving ecosystem that provides the gifts of clean water, air, and food to us and ask ‘How much should we leave?'”

The interplay of a still intact ecosystem, a hardy and diverse people, and looming threats brought Gulick, who has taken photographs around the world, to the Tongass.

Gulick, who has won the Daniel Housberg Wilderness Image Award from the Alaska Conservation Foundation and the Lowell Thomas Award from the Society of American Travel Writers Foundation for her work in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, differentiates between a ‘nature’ photographer and a ‘conservation’ photographer. The former photographs nature purely as a subject, while the latter “has a different focus—to use photographs to educate, inform, and inspire people to conserve nature,” she says. “In that way, we are more like journalists than just nature photography hobbyists. It’s our job to photograph both the ‘beauties and the beasts’—the gorgeous images as well as the ugly truths about the threats to nature.”

In the Tongass the beauty still outweighs the beast.

The Tongass National Forest contains nearly one-third of the world’s rare old-growth coastal temperate rain forests, and the largest reserves of intact old-growth forests in the United States. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

“We have an incredible opportunity to preserve the ecosystem and a way of life for both wild and human communities. In addition, the Tongass is globally significant for its ability to store carbon and regulate global climate. We have the very real chance to finally get it right somewhere,” she says.

Gulick sees her photographs as something more than ‘works of art’ or ‘moments captured in time’, but as a means to an end.

“As a conservation photographer, it’s my job not only to educate people with my work but to inspire them to act to preserve nature,”

In a July 2010 interview with mongabay.com, Amy Gulick talks about the species, peoples, and ecosystems of the threatened Tongass rainforest, while highlighting the role photographers can play in conserving the world’s last wild places.

AN INTERVIEW WITH AMY GULICK

Mongabay: What is your background?

Amy Gulick: I have been publishing both my photographs and stories since 1993 in publications including: Audubon, Sierra, National Wildlife, Outdoor Photographer, and Nature’s Best Photography.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in nature photography?

Amy Gulick: My two passions are storytelling and nature. A few strong images can capture people’s attention and entice them to read a story. Likewise, a story well told in words can be evoked with a few powerful images. I think that the combination of words and images is the most effective way to inform people about nature.

Mongabay: In your view how does photography inspire conservation?

The Tongass is home to some of the highest densities of both brown (grizzly) and black bears. For many bears, salmon are an important part of their diet. Rich in protein and fat, the salmon help the bears gain the necessary weight they need to survive winter hibernation. Toward the end of a good salmon season, the bears target the richest parts of the fish and leave the rest behind. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

Amy Gulick: To conserve nature and all its glorious gifts to us–clean water, air, food, etc.—people need to be inspired to care and act to make a difference. Photographs that evoke emotion can move people to care and act. The emotions can run the gamut of joy, anger, or sadness, but we won’t act to preserve nature if we don’t feel emotion when we look at photographs. As a conservation photographer, it’s my job not only to educate people with my work but to inspire them to act to preserve nature.

Mongabay: Do you think nature photographers have a responsibility to educate the public on conservation issues?

Amy Gulick: Many nature photographers simply want to enjoy nature and escape the stresses of the modern world and the harsh realities of the threats to our natural world. They are using photography as a way to immerse themselves in the beauty and joy of nature. I don’t feel that these folks have to be responsible for educating the public on conservation issues. A CONSERVATION photographer, on the other hand, has a different focus—to use photographs to educate, inform, and inspire people to conserve nature. In that way, we are more like journalists than just nature photography hobbyists. It’s our job to photograph both the “beauties and the beasts”—the gorgeous images as well as the ugly truths about the threats to nature.

Mongabay: What advice would you give an aspiring young nature photographer?

Amy Gulick: Photograph subjects you are passionate about, and look for unique angles to tell a story a different way. Don’t chase the same subjects that everyone else is photographing. Learn to write well—be clear and succinct. Pictures with no stories will be interpreted in as many different ways as there are people looking at the images. Above all, remember that there is only one species—homo sapiens–that is looking at your photographs. What do you want them to know and do after looking at your images?

THE TONGASS RAIN FOREST

Mongabay: What does the title of your new book, Salmon in the Trees: Life in the Tongass Rainforest, mean?

Bears play a significant role in spreading nutrient-packed salmon carcasses throughout the forest. Researchers say that one bear might carry 40 salmon in 8 hours from a stream into the forest. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

Amy Gulick: Salmon in the trees refers to a scientific discovery that shows a direct link between the salmon and forests of the coastal temperate rain forests of North America. Scientists have found a particular nitrogen variant in trees near salmon streams in the coastal temperate rain forests of Alaska and British Columbia. The variant is called nitrogen 15 and it primarily comes from the ocean.

So how did it find its way from the sea into the forest? It swam there, in the bodies of salmon accumulated from their time spent maturing at sea. How exactly does it get into the trees? When salmon leave the ocean and return to their freshwater birth streams and rivers to spawn, there are plenty of hungry animals waiting for them. The Tongass National Forest of Alaska is home to some of the greatest densities of both brown (grizzly) and black bears, due in part to the millions of wild salmon that fill the more than 4,000 spawning streams in this part of the world. Bears are responsible for moving a lot of salmon from the streams into the forest. Researchers say that one bear can carry 40 fish from a stream in 8 hours. At the end of a good salmon season, bears target the richest parts of the fish and leave the rest behind on the forest floor. Other animals scavenge on the carcasses, which spreads the nutrients from the fish farther throughout the forest.

Over time, the nutrients filter down into the soil and the trees and other vegetation absorb them through their roots. Scientists have been able to link nitrogen 15 in trees near salmon streams back to the fish.

Mongabay: What drew you to photograph this forest?

More than 50 species have been documented feeding on salmon, including: bald eagles, brown and black bears, wolves, ravens, mink, otter, sea lions, orcas, and people. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

Amy Gulick: The ecosystem in the Tongass National Forest is still intact. All of the species that existed at the time of European settlement in the 1700s are still here. Nothing is missing. But we’re on our way to carving it up, and without further protections it will just be a matter of time until we unravel this glorious cycle of life. I wanted to call attention to this phenomenal ecosystem and how it supports an incredible way of life for both wild and human communities.

Mongabay: What were some of your favorite subjects in the Tongass Rainforest?

Amy Gulick: There’s nothing quite as thrilling as watching bears catch salmon and interact with each other. When the salmon fill the streams, the whole place comes alive. Bears, bald eagles, ravens, and gulls concentrate in large numbers and it’s quite a show.

Since the Tongass is a coastal forest, the sea is an integral part of the area as well. Humpback whales, harbor seals, and Steller sea lions are exciting to watch.

Apart from wildlife, the forests themselves are stunning—so primeval you feel like you’ve gone back in time. Glaciers are a prominent and powerful feature in the Tongass as well. In addition, the local people live a way of life much closer to the land than most Americans. Fishing and hunting are not viewed so much as sport, but more as a way to fill a freezer for the winter. There has also been a cultural resurgence among the Native Indian cultures of the region over the past few decades—Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian, and their totem poles and regalia reflect the region’s vitality.

Mongabay: You’ve traveled to many places throughout North America and around the world, what makes the Tongass ecologically unique?

Bears and other animals spread salmon carcasses throughout the forest. The nutrients from the bodies of the fish filter down into the soil, and the trees absorb them through their roots. Scientists have traced a particular form of marine nitrogen found in trees near salmon streams back to the fish. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

Amy Gulick: Coastal temperate rain forests are extremely rare, covering just one-thousandth of the Earth’s land surface. They are rare because it takes just the right conditions for them to exist. The Tongass contains nearly one-third of the world’s remaining old-growth coastal temperate rain forests, and the largest reserves of old-growth forests left in the United States. While there has been damaging resource extraction in the Tongass—primarily clear-cut logging—there are still enough critical biologically productive watershed areas holding the ecological integrity of the ecosystem together.

We have an incredible opportunity to preserve the ecosystem and a way of life for both wild and human communities. In addition, the Tongass is globally significant for its ability to store carbon and regulate global climate. We have the very real chance to finally get it right somewhere.

Mongabay: How do locals view the Tongass forest?

Amy Gulick: This is a tough question because there are many varied opinions. But all of the local people I met value their way of life—fishing, hunting, recreation in both the forests and on the ocean—and they would be devastated to see this disappear. It’s who they are.

During my travels throughout the communities of Southeast Alaska, I got the impression that many people don’t feel that there are imminent threats to the Tongass. I can understand why many people might believe this because the Tongass covers 16.8 million acres (about the size of the state of West Virginia), and people are geographically isolated on both the mainland coast and many islands throughout this huge region. So unless clear-cut logging is visible to you, you don’t necessarily feel a sense of urgency to do something. But over time, it’s the systematic degradation of streams and forest stands, one at a time, that eventually adds up to failed watersheds and the breakdown of the ecosystem. It’s difficult to convince people of these threats unless they can see and feel the immediate effects.

THREATS TO THE TONGASS

Mongabay: What are some of the threats to the Tongass rainforest?

The Tongass is ranked among the top ten national forests in the United States for its ability to store carbon and regulate global climate. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

Amy Gulick: Industrial-scale resource extraction at an unsustainable rate is one of the biggest threats to the Tongass—continued logging and mining in sensitive areas. We don’t know how global climate change will affect the ecosystem, but we do know that salmon are very sensitive to water temperatures and to the timing and amount of water in the spawning streams at certain times of the year. Energy development and industrial-scale tourism are additional threats.

Overall, I feel that the single biggest threat is that of an old industrial mind set—one of looking at a place rich in resources and asking “How much can we take?” Instead, we should view the Tongass as a thriving ecosystem that provides the gifts of clean water, air, and food to us and ask “How much should we leave?”

Mongabay: What conservation measures would you like to see put in place to preserve the forest?

At 16.8 million acres (the size of West Virginia), the Tongass National Forest comprises about 80 percent of Southeast Alaska. Approximately 70,000 people live in the region in several dozen small communities scattered along the mainland coast and among thousands of islands. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

Amy Gulick: It is crucial that we preserve the most biologically productive watershed areas in the Tongass—those watersheds that have been identified as strongholds for salmon, bears, estuaries, marbled murrelets, Sitka black-tailed deer, and the ability to grow large trees. These areas are key to preserving the entire ecosystem.

Mongabay: There is a controversial bill in the Senate that has attracted some attention recently (SB 881). It would allow logging in 85,000 acres of the forest, over 50 percent of which is old growth. What is your view of this bill?

Amy Gulick: This is another tough question, because there is so much history that has led to this bill. The Sealaska Native Corporation is entitled by law to take ownership of approximately 85,000 acres of land that will be transferred to them from publicly owned lands of the Tongass National Forest. No one is disputing that the corporation is entitled to additional lands. What is being disputed is WHICH lands will be transferred. In the current legislation, the corporation has selected lands outside of its original selections and that is why Congressional approval is necessary. What concerns me most is what will happen to these lands. Regardless of who “owns” them, we continue to view the Tongass with the old industrial mind set of resource extraction at an unsustainable rate. If this continues, then it’s just a matter of time until we break the ecosystem as we have done in so many other parts of the world.

Mongabay: Having traveled throughout the forest and talked to many locals, do you think it is possible for locals and visitors to sustainably use the natural wealth of the Tongass forest without harming it irretrievably? How could such a harmony be achieved?

The rich waters of Southeast Alaska are home to many marine mammals including: humpback whales, orcas, sea lions, and porpoises. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest. |

Amy Gulick: I have a lot of hope for the Tongass and it’s the whole reason why I’ve pursued telling the story of this incredible place. There is still time to get it right.

Many locals value their way of life that living in this rare rain forest allows, and I do think that both locals and visitors can and want to tread lightly in order to benefit from the natural wealth and sustain it for the future. Southeast Alaskans are a tough, adaptable bunch that like where they live and will pretty much do anything to stay.

I think the locals are willing, but what we need is strong leadership within the U.S. National Forest Service, the agency tasked to manage the Tongass, in order to ensure this rare rain forest endures. To change the old industrial mind set is a painstakingly slow process, and we are running out of time. But the opportunity we have today to make lasting protections is as good as it’s ever been. And hopefully we’ll learn from the lessons that salmon in the trees teach us: that everything is connected; that this most magnificent rain forest thrives because all of its pieces still exist, and that people are an integral part of the whole glorious ecosystem.

For more information on Amy Gulick visit her homepage:www.amygulick.com.

In Southeast Alaska, salmon are a way of life. The commercial salmon fishery is a mainstay of the local economy and has been certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council. The health benefits of eating wild salmon are well documented, and many local people catch, clean, smoke, freeze, and can salmon for personal use. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest.

Every year, millions of wild salmon infuse an upstream flow of nutrients into more than 4,500 spawning streams throughout the Tongass. In return, the forest plays an important role in the life cycle of salmon. Trees shade the spawning streams, keeping the water temperatures cool for the developing eggs. Trees also prevent erosion from fouling the clean water and gravel beds the salmon need to lay their eggs. And fallen trees over the streams create protected pools for the juvenile fish and provide food for the insects they eat. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest.

In parts of the Tongass, trees help grow salmon, and salmon help grow trees. Near salmon streams, up to 70 percent of the nitrogen in the nearby foliage is of ocean origin—brought by salmon, delivered by bears, and drawn into the roots of plants. Photo by: Amy Gulick from her new book: Salmon in the Trees: Life in Alaska’s Tongass Rain Forest.

Related articles

Local voices: frustration growing over Senate plan on Tongass logging

(06/17/2010) Recently local Alaskan communities were leaked a new draft of a plan to log 80,000 acres of the Tongass forest making its way through the US Senate Energy and Natural Resources committee. According to locals who wrote to mongabay.com, the draft reinforced their belief that the selection of which forests to get the axe has nothing to do with community or environmental concerns.

Photos: Tongass logging proposal ‘fatally flawed’ according to Alaskan biologist

(06/15/2010) A state biologist has labeled a logging proposal to hand over 80,000 acres of the Tongass temperate rainforest to Sealaska, a company with a poor environmental record, ‘fatally flawed’. In a letter obtained by mongabay.com, Jack Gustafson, who worked for over 17 years as a biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, argues that the bill will be destructive both to the environment and local economy.

(06/02/2010) Radical, controversial, ahead-of-his-time, brilliant, or extremist: call Dr. Glen Barry, the head of Ecological Internet, what you will, but there is no question that his environmental advocacy group has achieved major successes in the past years, even if many of these are below the radar of big conservation groups and mainstream media. “We tend to be a little different than many organizations in that we do take a deep ecology, or biocentric approach,” Barry says of the organization he heads. “[Ecological Internet] is very, very concerned about the state of the planet. It is my analysis that we have passed the carrying capacity of the Earth, that in several matters we have crossed different ecosystem tipping points or are near doing so. And we really act with more urgency, and more ecological science, than I think the average campaign organization.”

Logging in Tongass rainforest would imperil rare species

(05/03/2010) According to a letter from three past employees of the Alaska Division of Wildlife Conservation to Sean Parnell, the Governor of Alaska, a proposal to bill logging the Tongass temperate rainforest would threaten two endangered species. In fact, the letter warns that if the bill passes and the company in question, Sealaska, proceeds with logging it is likely the Alexander Archipelago wolf and the Queen Charlotte goshawk would be pushed under the protection of the US Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Locals plead for Tongass rainforest to be spared from Native-owned logging corporation

(04/29/2010) The Tongass temperate rainforest in Alaska is a record-holder: while the oldest and largest National Forest in the United States (spanning nearly 17 million acres), it is even more notably the world’s largest temperate rainforest. Yet since the 1960s this unique ecosystem has suffered large-scale clearcutting through US government grants to logging corporations. While the clearcutting has slowed to a trickle since its heyday, a new bill put forward by Senator Lisa Murkowski (Rep.) gives 85,000 acres to Native-owned corporation Sealaska, raising hackles among environmentalists and locals who are dependent on the forests for resources and tourism.

U.S. approves logging of 381 acres of primary rainforest in Alaska

(07/17/2009) The Obama administration moved this week to allow clear-cutting of 381 acres (154 ha) of primary temperate rainforest in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, reports the Environmental News Service (ENS).

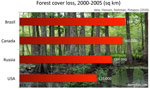

United States has higher percentage of forest loss than Brazil

(04/26/2010) Forests continue to decline worldwide, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS). Employing satellite imagery researchers found that over a million square kilometers of forest were lost around the world between 2000 and 2005. This represents a 3.1 percent loss of total forest as estimated from 2000. Yet the study reveals some surprises: including the fact that from 2000 to 2005 both the United States and Canada had higher percentages of forest loss than even Brazil.

World failing on every environmental issue: an op-ed for Earth Day

(04/22/2010) The biodiversity crisis, the climate crisis, the deforestation crisis: we are living in an age when environmental issues have moved from regional problems to global ones. A generation or two before ours and one might speak of saving the beauty of Northern California; conserving a single species—say the white rhino—from extinction; or preserving an ecological region like the Amazon. That was a different age. Today we speak of preserving world biodiversity, of saving the ‘lungs of the planet’, of mitigating global climate change. No longer are humans over-reaching in just one region, but we are overreaching the whole planet, stretching ecological systems to a breaking point. While we are aware of the issues that threaten the well-being of life on this planet, including our own, how are we progressing on solutions?

US Eastern forests suffer “substantial” decline: 3.7 million hectares gone

(04/07/2010) The United States’ Eastern forests have suffered a “substantial and sustained net loss” over the past few decades, according to a detailed study appearing in BioScience. From 1973 to 2000, Eastern have declined by 4.1 percent or 3.7 million hectares. Deforestation occurred in all Eastern regions, but the loss was most concentrated in the southeastern plains.

Housing developments choking wildlife around America’s national parks

(01/05/2010) Housing developments within 50 kilometers (31 miles) of America’s national parks have nearly quadrupled in sixty years, rising from 9.8 million housing units to 38 million from 1940 to 2000. The explosion of housing developments adjacent to national parks threatens wildlife in a variety of ways, according to a new study in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). “We are in danger of loving these protected areas to death,” says co-author Anna Pidgeon as assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Boreal forests in wealthy countries being rapidly destroyed

(08/12/2009) Boreal forests in some of the world’s wealthiest countries are being rapidly destroyed by human activities — including mining, logging, and purposely-set fires — report researchers writing in Trends in Ecology and Evolution.