Radical, controversial, ahead-of-his-time, brilliant, or extremist: call Dr. Glen Barry, the head of Ecological Internet, what you will, but there is no question that his environmental advocacy group has achieved major successes in the past years, even if many of these are below the radar of big conservation groups and mainstream media.

“We tend to be a little different than many organizations in that we do take a deep ecology, or biocentric approach,” Barry says of the organization he heads. “[Ecological Internet] is very, very concerned about the state of the planet. It is my analysis that we have passed the carrying capacity of the Earth, that in several matters we have crossed different ecosystem tipping points or are near doing so. And we really act with more urgency, and more ecological science, than I think the average campaign organization.”

Ecological Internet‘s online campaigns—with thousands of supporters around the world—have helped stop a palm oil company from deforesting a pristine island in the South Pacific; added pressure to the government of Madagascar to ban the exporting of illegally logged rosewood; and stalled an industrial logger in Papua New Guinea from clearcutting against local wishes to name just a few of the organization’s successes. Many of these issues were ignored by the big environmental groups and the vast majority of the media.

Glen Barry, head of Ecological Internet. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

“I really describe what we do as global grassroots advocacy. It’s taking grassroots issues and internationalizing them. That’s sometimes called the ‘boomerang effect’,” Barry told mongabay.com in a recent interview. “The boomerang effect is getting [local] concerns out to an international audience, so that those same demands are coming to the government and officials from the international community. This can really help those local people to have a larger voice.”

Ecological Internet has also become known in environmental circles for harshly criticizing larger and better known activist groups such as Greenpeace and the Rainforest Action Network for their continued support of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), which certifies wood products it deems sustainably harvested.

“[The] whole idea of certified forestry was completely usurped and the term made relatively meaningless, much like sustainable development has become, by the industrial logging as usual […] FSC logging is still the first-time logging of primary forests that are ancient ecosystems that contain the genetic and biodiversity materials that are very important for our and all species’ survival,” explains Barry, who has seen the process first hand while working as the Papua New Guinea World Bank rainforest specialist for four years.

“I just reached a point personally where if I was going to work on this for any longer, I was going to work to end this desecration of 60-million-year-old rainforests for, in some cases, toilet paper and lawn furniture.”

Barry sees NGOs that continue supporting FSC—and thereby industrial logging in old-growth forests in some cases—as contributing to ecosystem destruction and the worst kind of greenwash.

Protest of Rainforest Action Network (RAN). Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

“A real impediment to the movement to protect and compensate the people that are foregoing the opportunity costs of developing those forests is the cabal of everything from mainstream groups like WWF, Greenpeace, Rainforest Action Network, that in the early 1990s embraced the Forest Stewardship Council, and then the sort of dirty secret that no one would ever talk about is that FSC is primary forest logging,” he says, adding that “we challenge Rainforest Action Network, we challenge Greenpeace, to sit down and have a debate on this.”

Ecological Internet estimates that 60 percent of FSC-certified products come from primary forests. The FSC, for its part, has not released data related to this issue.

“It’s a cover-up. It’s greenwash. And there’s no way that we can go forward to governments and seek ways to compensate keeping primary rainforest intact, in my opinion, if we’re continuing to say that logging these millions-of-year-old masterpieces for consumer throwaway items is somehow acceptable,” says Barry, who adds that he would be happy to work together with these NGOs once they renounce all logging in primary forests.

Ecological Internet recommends not a moratorium, which is temporary, but a global ban on industrial logging in old-growth or primary forests, both in temperate and tropical regions. Barry argues that such a ban is absolutely necessary if our planet is not to suffer tremendous environmental upheaval.

Forest destruction in Papua New Guinea by RH Ramu Logging in 2009. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

“There is every reason to believe, and this can’t be proved definitively because we only have one planet to do experiments on (and we’re doing them),” he explains, “but I very strongly believe that we have surpassed the amount of impact on terrestrial ecosystems and primary forests in particular that is possible and still maintain the biosphere and a habitable planet.”

Barry says that ‘revolutionary change’ is needed to avoid ecological collapse, which according to Barry is not some distant specter, but waits on the horizon.

“It’s very likely that the global ecological system is going to collapse. It’s not even very likely: it’s certain,” he says. “If we cross thresholds, including the loss of intact terrestrial ecosystems which include primary rainforest and other forests, we are going to face an ecological collapse where there is going to be large-scale death and suffering, if not the failure of the global ecological system to maintain conditions in a range that’s favorable to life including humans.”

But it’s one thing to point to the problem, however awful, but another altogether to point to the solution: just what kind of change does Barry think we need in order to stave off ‘large-scale death and suffering’?

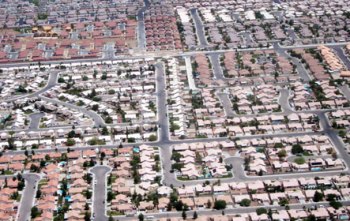

“There is going to have to be a number of changes: we’re going to have to in the over-developed world consume less, way less; we’re going to have to become way more efficient; we’re going to have to debunk the meaning of life being consumption; and find meaning in other things like community, ecology, hard work, and friends, within living sustainably and within ecology. But then there’s a lot of the world that is actually going to need more consumption just to meet their basic human needs,” Barry explains.

Barry criticizes larger environmental groups for not doing enough given the direness of the situation as he sees it.

“The efforts of the environmental community in regard to this threat are orders of magnitude insufficient,” he says.” There’s been a whole industry built up around environmental concerns, but an amazing amount of it is toward, you know, sustainable logging or loving the panda.”

Suburban sprawl out of Las Vegas, Nevada. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Small changes around the edges won’t be enough, according to Barry, but a global seismic shift is necessary to save not just the Earth, but the human race.

“There are times in human history when people need to stand up and they need to do what they need to do. Be that to end slavery, be that to end monarchy, there are times when people have come forth, and it’s usually not an overwhelming amount of people, there might be a relatively small group of people, but these people really see that something needs to be changed and that the option on the other hand is really wide-scale human suffering and death. They come together and they do what needs to be done.”

Barry says that while he believes it is possible for a non-violent ‘people’s revolution’ to bring about the changes he believes are necessary. He does speculate that if global society continues business-as-usual their may be some activists who see no other way to stave off ecological-collapse except byway of the destruction of private property—such as coal plants—and maybe even violence.

“I’m an incredible admirer of both [Mahatma Gandhi] and [Martin Luther King Jr.] and clearly we have to exhaust every non-violent means of trying to end these crises, which are going to cause such suffering,” Barry says. “But I don’t think that the meaning of [Gandhi and King’s] success is that there is never a time that we will ever fight again.”

In a June 2010 interview with Glen Barry, mongabay.com discussed with everything from early blogging to environmental issues in Papua New Guinea, from problems with the FSC to geo-engineering, and from primary forest logging to the possibility of global ecological collapse.

AN INTERVIEW WITH GLEN BARRY

Mongabay: What is your background?

Barry working with his community in Papua New Guinea. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

Glen Barry: I’m a political ecologist and conservation biologist. I grew up with parents who homesteaded, so was exposed at a very early age to ecology, growing our own food, and animal husbandry. I have a Bachelor of Arts in political science from Marquette University where I studied International Affairs then I was in the Peace Corps for some time in Papua New Guinea where I really fell in love with rainforests like many people before me.

I came back to the University of Wisconsin in Madison to do a Masters degree in Conservation Biology and Sustainable Development, and got sucked into academia and decided to do the full ride for a PhD. So, I have a PhD in Land and Resources which is at the University of Wisconsin where Aldo Leopold taught: the land ethic is such an important idea there that the Land Resources program is similar to an ecology program.

There I studied the use of the Internet for forest conservation and environmental advocacy, and then that work has carried over into my current organization, Ecological Internet, which formerly had been called Forests.org.

Mongabay: This is the fifteenth anniversary of Ecological Internet. Am I right?

Glen Barry: It sort of depends on where you say that it started. The original legal founding, which was paid for by the McArthur Foundation, was in 1999, so we just had our tenth anniversary. Although the work, that this is a continuation of, has indeed been going on for 15 years when we set up one of the first 10,000 web servers in the early 1990s.

Also, I was the inventor of blogging. I was the first person to comment upon other web materials, link it, and then list it reverse chronologically. There is some debate over who the very first one was, but I maintain that I am. It’s still on the web, and has been there since 1995; it’s very clearly there. But if not the first one—there may have been someone musing about their personal lives—at least I was the first political blogger: the first instance of an individual citizen harnessing the power of the internet for political commentary, and being able to publish that just like any large corporation could.

Mongabay: Tell me why you developed Ecological Internet and how that stemmed from your early, early days blogging?

Locals of Papua New Guinea. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

Glen Barry: Well from 1989 I was in the Peace Corps and shortly thereafter I got my first computer, and was exposed to some activists who were using a an early bulletin board system (BBS) that had one of the first Gateways connecting to the broader internet. In Australia it was called Pegasus; in the United States it was called Econet. From 1990 onward I was putting out information on the internet about Papua New Guinea.

Of course, there isn’t as much information about Papua New Guinea’s rainforest as the Amazon and the Congo, so there was really an appetite for that. So when I came back to do my Master’s degree that was a way to remain involved and to continue to harness the tools: we used the Gopher protocol and we put up the first web server on Forests.org in 1993. Then in 1995 we really started blogging—what began to be called blogging. Generally the definition of [blogging] is listing in backwards order, diary format, and then commenting on external content with your opinions. That continued in 1999 as we did some of our first development of true search engines using the same process that Google search engines use. So we have the first, and still only, true ecological search engines where we identify, myself as an ecologist, the best resources available on environmental topics. We just get the top URL page and then turn the spider loose to index the entire site. So, it’s kind of a hybrid machine-human editor system of which we are quite proud and that we think returns quite good search results.

Mongabay: What is the overall mission of Ecological Internet?

Glen Barry: We really seek to provide analysis, to provide information retrieval and archiving services, and to provide action alert capabilities that will lead to conservation outcomes.

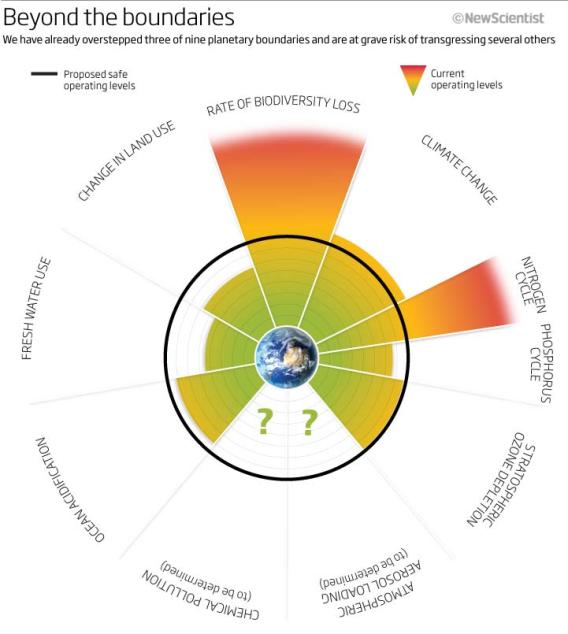

We tend to be a little different than many organizations in that we do take a deep ecology, or biocentric approach. We are very, very concerned about the state of the planet. It is my analysis that we have passed the carrying capacity of the Earth, that in several matters we have crossed different ecosystem tipping points or are near doing so. And we really act with more urgency, and more ecological science, than I think the average campaign organization.

Mongabay: What has been some of your organizations biggest successes?

Cut logs in Papua New Guinea by RH Ramu Logging in 2009. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

Glen Barry: I think we really fill a unique role: our network reaches at least 100,000 people around the world by email and several tens of millions more on the web. Virtually every major forest conservation group or individual is on this list. I really describe what we do as global grassroots advocacy. It’s taking grassroots issues and internationalizing them. That’s sometimes called the boomerang effect.

For example, in the last year we were able to hook up with a group of like-minded people that were putting out information on Madagascar [including mongabay.com]. You have some people concerned in Madagascar, as was the case, about illegal logging that was going on with rosewood. They are talking to officials, but getting the cold shoulder. The boomerang effect is getting those concerns out to an international audience, so that those same demands are coming to the government and officials from the international community. This can really help those local people to have a larger voice.

Over the years we have participated in several dozen campaigns that I believe were victories. Some of them we contributed by internationalizing others’ campaign efforts and in some of them we pretty much ran the campaign ourselves.

A year ago there was a plan by the Malaysian Land Management organization FELDA to start a large oil palm plantation near Manaus [in the Brazilian Amazon]. This was something they were broadly on record saying they were going to do, and as far as I know we were the only organization that campaigned on that issue. We were able to generate such protests and concern that it ended up that the Malaysian government dissolved the plan even though there was a long record of them having spoken of doing this.

So, we really depend on ecological science, we are seeking ecological sustainability, and we carefully choose campaigns where we feel that there is some target where we can voice a specific demand that will move the policy debate further, either by naming-and-shaming or by just providing information that may not have been known by the policy makers.

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

Mongabay: What makes Papua New Guinea unique in ecological terms?

Glen Barry: Well, Papua New Guinea is an amazing country. It contains the third largest intact rainforest on the planet; it is undergoing a tremendous boom in resource development; and it is becoming quite important geo-politically for its gold, minerals, oil, and timber.

A quarter of the Earth’s languages, 700 languages, are spoken in this one country of 6 million people. What you have is a country where there is a huge cliff, followed by a big trench, followed by a cliff, followed by a mountain all the way across the country. What you had was different microclimates, and very similarly to the speciation of plants or animals, you had human cultures radiating. So, from one mountain valley to the next mountain valley, which may only be 5 kilometers apart but is essentially completely isolated, is a completely different language group with each of those people having different uses for the forest, different spiritual understandings, and different agricultural understandings. The cultural diversity is just mind-boggling; it’s unmatched anywhere in the world.

One of the really unique opportunities that there is in Papua New Guinea is that at least 90 percent of the land is clan or communal land ownership. Whereas in many countries, such as Malaysia or even Brazil, where there can be indigenous people that have lived there for quite some time but the governments can come in and claim ownership and remove the resources, in Papua New Guinea at least theoretically you have the potential that if you can convince that tribe to forgo industrial development, there is a real urge then to pursue ecological alternatives based on standing forests. If you can do that they really have the legal right and that will be held-up in court. Now there’s a lot of corruption around that and you certainly can bribe the big man, but there is an opportunity for campaigning that, because of these land rights, is really quite exciting and shows the potential to get people involved in protecting and conserving their own land.

Mongabay: Environmentally speaking, what are the largest issues now facing Papua New Guinea?

Forest destruction in Papua New Guinea by RH Ramu Logging in 2009. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

Glen Barry: For some time the industrial logging mafia, if you will, that arose in the 1950s in the Philippines, progressed to Thailand, then moved onto Malaysia and Indonesia, have been in Papua New Guinea. Particularly in the case of Papua New Guinea, Malaysian logging companies have over the last 15 years virtually taken over the government. I know that’s a strong statement, but the extent of the corruption is unbelievable.

So you have these companies coming in where there are still many large chunks of rainforest that have very small population densities, and for the equivalent of a very small amount of money they are buying access to these resources through corruption. There is a terrible corruption situation in Papua New Guinea which really affects everything from schools, to roads, to education. This should be a very rich country; there is no reason for it not to be.

There also is a large liquid natural gas project underway by Exxon Mobil that is going to have an amazing pipeline that comes down through those rugged mountains under the ocean for many kilometers and then comes to a processing plant.

The country has been described as a sea of oil, with mountains of minerals, and forests. It really appears that anywhere you went and dug—this is a slight exaggeration, but not that slight—there would be some exportable mineral.

Now, I work in a very special province called Madang Province in particular, and that is on the north coast of Papua New Guinea. This is a very lovely province; it has been described for a long time as the ‘jewel of the south Pacific’; one of the most special and beautiful places in the world. It’s incidentally where I was in the Peace Corps; I am married to a woman from there, my daughter, of course, is from there, and we have family there. But things have really gotten out of hand in recent years.

Sign advertising Pacific Marine Industrial Zone. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

Where today there is one tuna fish factory along the coast, there is a plan to create an industrial zone with World Bank support that would construct ten tuna fish factories and would make a huge industrial tuna fish area: the size of something that you would see in the Philippines. Now this is some of the last, not-yet overfished tuna resources in the world. It’s clear that very large Filipino and Chinese companies are coming in and are going to take sort of an idyllic small-scale fishing area and turn it into an industrial wasteland. So, there’s quite a bit of opposition to that.

There is also over 1 million hectares of rainforest here, and the second project is that Rimbunan Hijau—the notorious loggers described as ‘robber barons’ in Papua New Guinea in the past—has started a project that subsequently was deemed illegal. They were logging essentially 20 hours a day with spotlight, as quickly as they could, removing timber in a very very destructive way. They say it’s selective logging, but it’s essentially selecting all of the trees and logging them.

This issue was a part of the success that we have enjoyed. We have been able to work with two different groups of landowners, including the tribe I belong to, and that project has now been declared illegal. For the last six months the logging has stopped. However, it just takes one more bribe or one more thing to undo that. It looked like it was sort of fate accompli: where for sure this was going to go through and that whole area was going to be cleared. We have managed to slow it down and perhaps stop it—and we continue with those efforts.

And if that isn’t worse enough, in this one province there is a huge Chinese Nickel Mine, which will be the largest Chinese mine this side of China. They are there in a very rugged area, essentially strip mining and having a slurry pipe that goes for over a hundred kilometers down to the coast through pristine forest, and then the processing is done on the coast. The plan is to dump a hundred million tons of mining waste over its twenty year life directly into the Astrolabe Bay, which as I said, is one of the last really good tuna areas. This submarine tailings disposal system is banned in most countries, including China I believe. They say it’s ‘deep water disposal’, but it’s a hundred and fifty meters. It’s not being capped on the seabed in anyway.

Community meeting in Papua New Guinea. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

In all three of these cases local people are extremely concerned. There is reason to believe that the corrupted, essentially despotic, leader of the country, Michael Somare, is involved. Somare was the country’s founder, but in Mugabe-like fashion is working to have his son takeover and is selling out resources from underneath other tribes. The landowners in the logging area were told that Michael Somare, the Grand Chief, was saying that these were his forests and that he wanted them logged, which is nonsense.

It’s really a case of three huge resource-development projects that will completely decimate this beautiful province, but we’ve been able in the last year to really bring an international campaign focus to that, whereas no one else had really doing that on Papua New Guinea. We are the first to internationalize these issues, and all indications are that it has really revealed the depths of the corruption, and we are delaying if not cancelling some of these projects.

Mongabay: Given the biological and cultural importance of Papua New Guinea why do you think it is that the Amazon, Congo, Malaysia and Indonesia receive more attention by the big conservation organizations? Papua New Guinea always seems to be left out of the discussion.

Glen Barry: Well, I think there are several reasons. Papua New Guinea is an extremely difficult country to work in compared to the countries you just listed that have a large urban infrastructure and access to decent Internet. Papua New Guinea was explored and discovered, if you will, by the west later. I just think that there is less known about it because there have been less people working there over a lesser period of time.

Largely, unfairly, the country has a reputation for security issues, which while real are not that different from pretty much any country in the world. You know I speak the language fluently; married there; I engage in tribal politics; I’m working in the country as close to a Papua New Guinea national that an Irish-Bohemian guy from near Chicago can. It is a very challenging place to work [in Papua New Guinea], and I don’t think there are very many conservationists that go there and get outside the two or three relatively major cities and actually have an understanding of the land system and people’s reasonable aspirations to improve their life and have development.

THE FOREST STEWARDSHIP COUNCIL (FSC)

Mongabay: One of Ecological Internet’s long-standing campaigns is focused on the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). In your view what are the problems with this certification group?

Protesting the FSC in New York City. Photo courtesy of Ecological Internet. |

Glen Barry: Just a little bit of background first. I’ve been a rainforest conservationist now for over 20 years, and have had diverse experiences from founding and working in local NGOs, to being the Papua New Guinea World Bank rainforest specialist for four years, as well as academia. I’ve really investigated these issues and been at the table from many different perspectives. For many years, I worked thinking that we could do sustainable logging.

[Sustainable logging] efforts in Papua New Guinea involved people carrying small saw mills to the forest, felling one or two trees per hectare, milling them on site, and then carrying them out. And that was eco-forestry. That was mimicking the gap dynamics of the forest and harnessing the natural regenerative power.

So, many of us were working for what we considered ecologically sustainable forest under very strict ecological management plans. But that whole idea of certified forestry was completely usurped and the term made relatively meaningless, much like sustainable development has become, by the industrial logging as usual—really just doing the best management practices, the obvious things, like not rumbling their bulldozers through the water and not ripping off local people, that they should’ve been doing all along.

FSC logging is still the first-time logging of primary forest that are ancient ecosystems that contain the genetic and biodiversity materials that are very important for our and all species’ survival, and also are the ecosystem engines that power the processes that make the Earth habitable.

I just reached a point personally where if I was going to work on this for any longer, I was going to work to end this desecration of 60-million-year-old rainforests for, in some cases, toilet paper and lawn furniture. This has been borne out in my scientific studies and my research: there is every reason to believe, and this can’t be proved definitively because we only have one planet to do experiments on (and we’re doing them), but I very strongly believe that we have surpassed the amount of impact on terrestrial ecosystems and primary forests in particular that is possible and still maintain the biosphere and a habitable planet. I often use the term ‘old forests’ to also capture regenerating secondary forests, planted natural forests that are allowed to age and forests that are approaching old growth status. We have lost more of that type of forest than we can afford to lose

You know, there’s a recent scientific paper out that identifies various tipping points, and this is one. In my scientific opinion there is just no more justification for industrial logging of primary forests. Now, the small-scale community milling the timber themselves to make furniture locally—no problem! That’s entirely different than a hundred thousand hectare concessions that are selective, but are so dwindling the genetic stock through taking out the high quality stems that what you have left is a completely different structure, a completely different dynamic and composition, and is on its way to becoming a tree farm.

So, somewhere along the lines sustainable forest management went from ecologically sustaining these patterns and processes to sustaining timber yields. I think there is no problem with sustaining timber yields in naturally planted forests that are free of toxins and with secondary forests that are historically logged, but I really strongly believe that the science shows that we need to hold onto intact, large, core ecosystems as planetary reserves, if you will, to allow the weather and the other ecological patterns to which we are accustomed to continue to operate.

Mongabay: So, would you recommend then a complete moratorium on industrial activity on logging in old-growth or primary forests, both temperate and rainforest?

Lone Brazil nut tree in deforested area in Brazil. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Glen Barry: That is precisely what our overall commitment is to, and that is what are campaign is. But we are not for a moratorium, which by definition is temporary. In our experience industrial primary forest logging is irredeemable and after a moratorium things return to business as usual. Ecological Internet supports a permanent ban on industrial scaled primary and old growth forest logging, and reasonable compensation measures for doing so.

So, the background for our campaign on the FSC: the FSC is a strategic choice of a first target. We can’t make this call to end primary forest logging and protect and restore all remaining old forests unless we get at some of the people that are greenwashing [industrial] activities that are going on there.

Because time and time again what we run into when we’re negotiating with government officials, when we’re talking with local people and we’ll say ‘well, you have a very valuable resource here, long-term almost certainly you would benefit more by maintaining the forest intact, carrying out small-scale eco-forestry and other activities, and finding ways to benefit from standing forest’, and inevitably the response is: ‘oh, but no, Greenpeace says we can sustainably log this’.

So, a real impediment to the movement to protect and compensate the people that are foregoing the opportunity costs of developing those forests is the cabal of everything from mainstream groups like WWF, Greenpeace, Rainforest Action Network, that in the early 1990s embraced the Forest Stewardship Council, and then the sort of dirty secret that no one would ever talk about is that FSC is primary forest logging. They could not be meeting the market that they have created for supposedly well-managed, certified, sort-of-claiming-sustainability, without accessing primary forest. There wouldn’t be enough timber.

What has been amazing in this campaign is that our estimates are that 60 percent of the forests logged with FSC certification are indeed primary or old-growth forests, and we were shocked to find—perhaps because they don’t want anyone to know—that this information is not collected or collated according to FSC, that they do not, in their database of certifications, make any effort to gather this information.

So what we were left to do is look at their national figures and estimates in a particular country what is generally the type of logging that is going on there. In a country like Peru there is very little secondary forest logging going on—there’s some—but not a lot, so from there and some other South American countries, and from Canada and Russia, a lot of that timber that is coming out is primary forest.

Clear-cut logging in Alaska. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

We did the very best that we could. We have been sort of picked on for our estimates, but I questioned a board member of the FSC at the European Forest Movement meeting last year in Switzerland, and they said ‘they do not know; they do not have that information’.

And then you have a group like Rainforest Action Network (RAN) who assures us that they are committed to ending primary forest logging, yet they are a founding member of FSC and they have asked to have that information provided and it’s not being provided. So, there’s a real dishonesty behind the idea that the FSC is the solution to forest protection.

I’m just also very disappointed in FSC and all these groups that despite millions of protest e-mails being sent and tens-of-thousands of people raising concerns, they continue to portray this as just ‘one guy on the Internet who has a beef’ and seemed to suggest that this isn’t important.

It’s a cover-up. It’s greenwash. And there’s no way that we can go forward to governments and seek ways to compensate keeping primary rainforest intact, in my opinion, if we’re continuing to say that logging these millions-of-year-old masterpieces for consumer throwaway items is somehow acceptable.

So this is a battle that has to be fought before we then go on together to end primary forest logging.

Mongabay: What would be ways to fix the FSC? If you could have your wish what would you like the FSC to do tomorrow?

Glen Barry: Well, to do tomorrow would be to shut-down. That would be ideal. I don’t think they are able to reform themselves to the extent to which they are dependent on primary forests.

But there is something they could do. They have their policy on ‘high conservation value forests’, which is essentially a protected-area set aside scheme; when they are logging in primary forests they will set aside about ten percent of the concession in a protected area. Fairly typical. Our point would be that ALL primary forests are ‘high conservation value forests’, so under their existing rules if they limited themselves from primary forests and declared all forests of that type to be ‘high conservation value forests’ then they could continue with the certification of natural planted and naturally regenerating secondary forests.

Now there are concerns with the plantations as well, and while we sympathize with those concerns we haven’t campaigned on them as much. But we really believe that plantations need to be based on native-species—native-genetic stock—and be trying to pursue ecological restoration which then may also provide timber products.

But the reality is that economic growth based upon leveling the ecosystems that make the Earth habitable, that era in history, is drawing to a close. We can work for ecologically sufficient policies now—while there’s still a relatively large amount of these forests intact that can serve as models for ecological restoration, that can provide genetic materials for ecological restoration—or we can pretty much log down to where the only primary forests are in protected areas, and many of those will probably be logged too. Then primary forest logging will end because there won’t be any more forests to log.

It is our firm ecological belief that we are at or approaching the point where we cannot lose more primary forest and still maintain the global biosphere as well as regional climate and soils, and all the ecological processes that these special places provide.

Mongabay: Given that there’s almost 7 billion people on Earth, by 2050 there’s estimated to be 9 billion, consumption rates are rising in places like China and India, how do we balance global demand for paper, timber, furniture, housing, and any other wood-related products and still preserve the remaining primary old-growth forests?

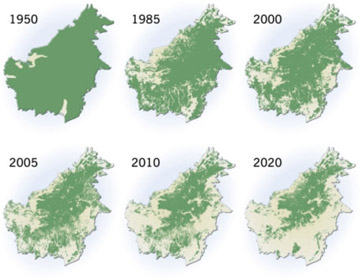

One way of viewing regional deforestation: extent of Deforestation in Borneo 1950-2005, Projection to 2020. The island of Borneo is split between Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Glen Barry: Well the balance has to be towards protecting those remaining primary forests. If it’s given the choice between allowing softer toilet paper for a growing population or keeping the Canadian boreal forest intact, we have to choose intact forests, because these are the sponges of water, these hold tremendous amounts of carbon. We’re at the point where we are breaking off pieces of our house to burn in the fireplace to keep ourselves warm.

Ecological Internet does engage with broader issues of ecological sustainability, justice, and equity, and I think we’ll get to some of those questions, but the point is that there are ways of meeting the needs for timber products that does not require industrially logging primary forest. We’re going to have to use less wood and we’re going to have to make making a guitar, or something beautiful, from a very old primary forest tree as something that’s socially unacceptable, like cutting off the hand of a gorilla and using it for an ashtray.

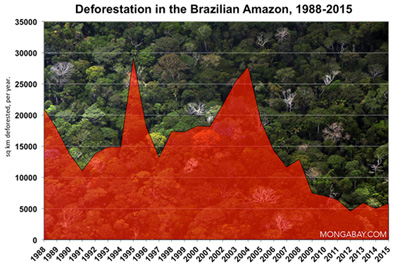

There has to come a realization that however many people we have, that it’s very likely that the global ecological system is going to collapse. It’s not even very likely: it’s certain. If we cross thresholds, including the loss of intact terrestrial ecosystems which include primary rainforest and other forests, we are going to face an ecological collapse where there is going to be large-scale death and suffering, if not the failure of the global ecological system to maintain conditions in a range that’s favorable to life including humans.

So, it’s really a matter of like an individual that’s smoking and doing harm to themselves; we have to as a society, as global citizens, realize that this idea that there is pristine forests that we can just essentially maul to make consumer items that those days or gone—as are factory fisheries. There’s many instances where there’s really a choice between stopping the very heavy unsustainable industrial consumption of resources or having a decade or two more of the artificial economic growth from them and then not having the forests, not having that revenue, and not have the ecological services. Take care of it now or it will be taken care of later and it will be a lot more difficult.

Mongabay: You grew up and you live at least part-time in the United States, which is the largest consuming nation ever and a lot of the United States is as materialistic as any other country in the west. Yet on the other hand I think most people in the United States would say destroying rainforests is a bad idea, and destroying old-growth forests is a bad idea. Do you think it’s simply a matter of a lack of awareness as to where these products are coming from? In other word, how do you make a place like the United States consume less? A place that has been built—at least the last fifty to a hundred years—on rampant consumption both of our own native forests and of forests around the world. How do you wake people up to the fact that their toilet paper, or their throw-away cup, or their fast-food container may be coming from an old-growth forest?

Glen Barry: Again, starting at the broad picture for context and then zooming in. It is absolutely clear that human industrialization and the global acceptance of the western model of destroying resources for economic growth is a disease upon the Earth. The way that the western world has lived for three hundred years has only been able to exist because after the forests are cleared here there’s other place where we can go into their forests. And we’re going to run out of great big huge forests to clear.

It is a consumption issue. It’s a population issue as well. But it’s the old IPAT equation: the impact is the population times the affluence and the technology. The basic point being that one American does way more damage than an individual in a not yet over-developed country. So, there are huge issues of human rights, injustice, and economic inequity involved in this.

Turkana children in northern Kenya. The Turkana deal frequently with famine. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

I really believe that America and Europe, and increasingly China and India, that these economies, based upon what you might call the growth machine are really eating the ecosystems that make life possible in order to give us cheap consumption. So, there is going to have to be a number of changes: we’re going to have to in the over-developed world consume less, way less; we’re going to have to become way more efficient; we’re going to have to debunk the meaning of life being consumption; and find meaning in other things like community, ecology, hard work, and friends, within living sustainably and within ecology. But then there’s a lot of the world that is actually going to need more consumption just to meet their basic human needs.

Now, I have written as a political ecologist of the fact that we are so far along on these issues, and the fact that if even a portion of the not yet over-developed world rises to the extremely wasteful lifestyle of an average American, this planet will be killed. Life will end here for humanity, if not for all complex life, if not for all life in total.

I’m writing a book currently called New Earth Rising, which is nearly completed, which really investigates what are the series of actions which we could take to stop this growth machine, to stop this consumption as the meaning of life, and that may involve a people power revolution that initially is people taking to the streets and protesting. But the time is short and if this continues to be rebuffed, these concerns, and minor reforms are made around the edges, tinkering around the edges, while at the same time these ecosystems are being destroyed, we really believe that the Earth, and human beings, and survival of all species is worth fighting for.

Academically, I have an interest in exploring what might be some more robust response, including sabotage or even an insurgency.

We really strongly believe that if this growth-machine to provide consumption is not stopped that it will mean an end to being or at least collapse into a situation where the few remaining humans who are around will not be living prosperous, good lives.

Mongabay: You’ve long been critical of some of the large conservation organizations; you mentioned a few of them already: Rainforest Action Network, WWF, and Greenpeace. How would you like to see these organizations change?

|

Glen Barry: Well, firstly, they have to own their policies. These groups have co-founded FSC. It’s been going on for nearly twenty years. We have ran a campaign against these organizations including FSC, for over two years, have generated millions of protest emails and we have yet to receive one substantive response to what are pretty reasonable concerns.

How is that an organization, such as Rainforest Action Network, which until recently was run by a very gifted accountant, has no ecological science staff? How is it that they are setting the policy that logging primary forests somehow protects us? And why won’t they engage in a debate to defend that position?

I think as they’re aware there’s a whole range of issues of how FSC has failed besides this primary forest logging issues, we have talked about the plantation issues, but also the control of the wood standard and the fact that you can have as little as ten percent certified content wood-fiber mixed in with other fibers of not certified nature and still have an FSC seal.

It’s clear from the FSC Watch website that has been tracking this—including Simon Counsell, who was a founder of FSC—that by just about any standard, FSC has been a failure. There have been illegally-issued certificates; it is still primary forest logging; and it’s not getting at the consumption side of the products: should we be building markets for timbers from primary forest? Has there ever been an instance where a market has been created and then it hasn’t led to unsustainability? And so, we challenge Rainforest Action Network, we challenge Greenpeace, to sit down and have a debate on this.

Then they have vilified us, and I’m kind of a controversial figure, so they just write-it off. But it’s really nonsense; they are doing a grave disservice to the planet.

Actually the campaign is growing. The New York Climate Action Group recently protested at the New York fundraiser of Rainforest Action Network, and did street theatre and protested outside a fancy, self-congratulatory fundraiser that they were having. Indications are that quite a few campaigners within these [FSC-supporting] groups agree that it’s time to take a stance that industrial scale primary forest logging has to end.

But I have some various theories as to why [these conservation organizations still support FSC]: I think a lot of these people from RAN and Greenpeace come from a background of loving to work from wood; they’re woodworkers; and they appreciate the beauty of the wood—it certainly is fantastic. But you have to ask yourself a question: can we ecologically sustainably continue to have this product or not?

I think there’s been a real lack of critical thinking. As you have organizations that are around for decades and decades, there’s going to be times where they pursue conservation strategies that don’t work and there has to be mechanisms within these organizations for change. It’s not necessarily a failure: they tried something it didn’t work. But how do they move on then and acknowledge that—without feeling that somehow they have lost face?

So, we will continue with our campaign to get these groups to stop their support of FSC logging as a first step to all of us then working to get a global ban on industrial primary forest logging, including large-scale ecological payments for the people who are foregoing [industrial logging] mostly to help establish cottage industries from standing forests. But we can’t do that so long as these supposedly radical groups are providing greenwash apologist cover for industrial logging.

REDD (REDUCING EMISSIONS THROUGH FOREST DEGRADATION AND DEFORESTATION)

Mongabay: What would your definition be of a REDD program that would be both effective and would preserve these forests?

Intact rainforest in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

Glen Barry: Well, REDD is another example, along with certified forestry and sustainable development, of a fantastic principle that is in the process of going wrong as industrial interests and governments have changed its meaning.

To me, REDD was initially a vey simple idea of paying communities and governments to strictly protect primary forests and something I had been working on for decades in Papua New Guinea given the land tenure system there of resource-owners, local people, and governments being paid to protect and preserve the rainforest. If carbon money is going to be used for this there’s every indication that that would be the maximal way to keep carbon both sequestered, and there’s been new science in the last couple years that suggest, at least for now, primary forests continue to remove much new carbon and that this is a continuing sink.

So, the definition of REDD is the rich paying the developing countries directly to maintain these forests in a standing protected condition. That was how I always envisioned REDD. Now, the REDD+ proposals that have come out have really shifted that emphasis from preservation and protection to what you would call conservation. So there is a strong effort to have so-called sustainable forest management, which is industrial logging of primary forests. That somehow there could be elements of ‘sustainable forest management’ in primary forests that could be compensated under REDD. NGO greenwash of FSC set the stage for this.

As you know there is just so much uncertainty of what exactly [REDD] is going to do, but it is clearly moving in that direction, as well as the fact that there are elements of people in this debate that would like to see plantations be eligible for monies under this effort to tie-up carbon, and protect forests and biodiversity at the same time.

Now the other issue to me is that I really believe the only way the world’s rainforests and primary forests are going to be protected is if the opportunity costs of the people that are living there are met, and they get an income for keeping those forests intact. I see that as being so important that I was willing to stomach the idea that the carbon offset markets might be the mechanism that would pay for that. I guess my concern, as with many other NGOs, has been the idea of the rich buying an offset—that’s a controversial idea.

But I’ve come to believe that there is no way that carbon offset markets as currently envisioned could or should be used for anything other than preservation or protection.

The problems on those two sets of issues—the carbon markets and the types of issues that will be eligible—have really made me think that there is no way that this is going to actually, in fact, be a good force for carbon, for local people, and for biodiversity. That once again our failure to more fundamentally reform ourselves away from viewing intact ecosystems as resources for consumption means that this is doomed for failure.

There’s very little chance I see that any appreciable carbon reductions could be realized anytime soon from the program as it is currently envisioned.

Mongabay: Ecologically speaking why are plantations not a forest in terms of biodiversity and carbon? Why should they not be included in both REDD or FSC?

Oil palm plantation from the air in Sabah, Malaysia on the island of Borneo. Photo by: Jeremy Hance. |

Glen Barry: Well, in many cases, historically those areas that are planted with plantations were primary forest, and even to the extent that there is a restriction on immediately planting new plantations in freshly cleared forest, you’re still increasing the land pressures on a finite land space. For example, this land area becoming plantations means it can’t be used for soybean farming, which means the soybean farmers have to go into the forest, or consider that same example but with cattle ranching.

There was just a study that came out that showed that this precise scenario was happening with soybeans. Soybeans was not directly, to a large extent, clearing rainforest, but the large-scale usurpation of land was forcing people to go into rainforests to do other activities.

That is a big reason of our critique of biofuels as well. You’re already using about 50 percent of the photosynthetic potential of the planet, if other species, if ecosystems are going to have any of what remains, we can’t think that we are going to power human-industry by more intensively managing the land. So, there is that broad land use issue.

As well as the fact that a great deal is made by the timber industry that planted trees are removing carbon and then that carbon is tied-up in products, and so they would argue, in fact, that this is a means to remove carbon. That’s just simply nonsense.

There have been studies that have been done that show the vast majority of paper and timber products are back in the landfill decomposing within two years. To say that taking this land—which may have regenerated back into natural forest or might have remained with the local people to do agroecological work—and instead put it in a mono-culture which relies heavily on toxic chemicals, which is not native species, which frequently is on land that has been stolen from local people, to say that that is a solution, that more consumption, more intensive use of the land, is somehow going to have a carbon benefit is just nonsense.

The best thing that we could do in terms of old forests and climate change is that we could protect the remaining primary forests and we could assist remaining remnants to expand and regenerate. In many cases it will do so naturally by itself through succession, or [expansion] may involve replenishment planting to help it expand. But the answer is more old forests, which hold disproportionately more carbon both in their biomass as well as in their soil, and not additional industrial disruption of soils and ecosystems.

GLOBAL ISSUES

Mongabay: According to the UN and most scientists the world is facing a perfect storm of crises: climate change; the food crisis, which is ongoing; water shortages, which is both ongoing and predicted for the future; deforestation; population growth; mass extinction; marine collapse; ongoing poverty and injustice. What do you see as the greatest, most pressing issue facing us?

Top: Children in Akavandra, Madagascar. Fifty percent of children in Madagascar “suffer retarded growth due to a chronically inadequate diet,” according to the World Food Programme. Bottom: Multi-colored beetle from Mount Kenya represents one of millions of species, most unknown to scientists. Photos by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Glen Barry: I think the biggest thing is all of those issues you mentioned in conjunction, happening at the same time. Never, with perhaps the exception of the rise of the blue-green algae which made the oxygen atmosphere, have we seen such a massive and much more rapid change than we’re seeing in ecosystems.

So, I am extremely concerned with fragmentation of forests in conjunction with reduced water availability, in conjunction with climate changes, in conjunction with toxins introduced into the area. We’re getting ourselves into an area—I consider myself an expert in the global ecological system—where we’re not only talking about ecosystem collapse of a community or maybe a region, but we’re talking about continental-scale and global-scale ecological collapse.

The science on this is just unequivocal. It starts thirty years ago with the limits to growth literature that highlighted the issue of exponential growth and how that cannot be maintained indefinitely, then the Millennium Assessments, and now the recent Global Biodiversity Outlook (GBO-3). Ecology is a relatively new science. A lot of what we know about the global system, about how the Earth system, or Gaia if you will, works has really only been discovered recently.

While we would have liked to have had that information when America was developing to act on, we didn’t. But we do have that information now and we have a responsibility to act upon it. I really believe that the Earth system is nearing collapse. That we are going to see whole regions, and nations, and continents not having water, not having food; that there’s going to be a really apocalyptic-type situation, unless we can reign in this population, economic, and consumption growth. There are limits to growth. The fact that technology put off those limits for a few decades does not mean that the limits have been eliminated, it just means that we are that much further past the carrying capacity.

The efforts of the environmental community in regard to this threat are orders of magnitude insufficient. There’s been a whole industry built up around environmental concerns, but an amazing amount of it is toward, you know, sustainable logging or loving the panda. There are very few people that are speaking out on the coming global ecological collapse and are promoting solutions, which however politically difficult are ecologically sufficient to actually solve these problems.

Mongabay: How do we stave off this ecological collapse? What are some of your top solutions?

Sunset over the Tabin Wildlife Reserve rainforest in Sabah, Malaysia on the island of Borneo. Photo by Jeremy Hance. |

Glen Barry: First of all, we have to completely put aside any idea that we are going to geo-engineer a biosphere. Discussions of geo-engineering are dangerous, distract from the immediate social and personal changes that need to be made, and are frankly more of the technology that has caused the problem in the first place.

We can’t even keep the invasive zebra mussels out of the Great Lakes and now we are going to engineer a biosphere? We’re going to engineer the system that makes life habitable for all of us? It’s just nonsense and it’s dangerous.

What we need to do is take a hard turn and go back to nature. We need to understand that the human endeavor has to exist within a context of intact ecosystems. There are still, in my opinion, enough intact ecological systems that if protected, assisted to expand, if consumption was brought down and made more equitable, that we could power-down, pull-back, and have reasonable lives full of sports and loving family and community, but just not having that third automobile and fourth TV.

Quite aside from the question of whether a revolution would be violent, which it doesn’t necessarily have to be—there’s been many people’s revolutions—there clearly needs to be some sort of revolutionary break with regarding growth of the economy at the expense of ecosystems as being the fundamental measurement of the well-being of the people, their economy, and their land.

There are times in human history when people need to stand up and they need to do what they need to do. Be that to end slavery, be that to end monarchy, there are times when people have come forth, and it’s usually not an overwhelming amount of people, there might be a relatively small group of people, but these people really see that something needs to be changed and that the option on the other hand is really wide-scale human suffering and death. They come together and they do what needs to be done.

In that case some of the specific things that we have highlighted as being central to achieving global ecological sustainability is what we’ve already discussed: we can’t lose more primary forest, in fact we need more old forests, so we have to allow natural forest to regenerate and age through replanting and succession.

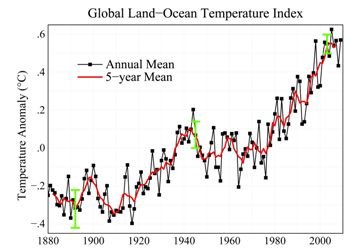

Except for a leveling off between the 1940s and 1970s, Earth’s surface temperatures have increased since 1880. The last decade has brought the temperatures to the highest levels ever recorded. The graph shows global annual surface temperatures relative to 1951-1980 mean temperatures. As shown by the red line, long-term trends are more apparent when temperatures are averaged over a five year period. Image credit: NASA/GISS. |

Secondly, there is no way that we can burn the remaining coal resources or tar sands or oil shale or synthetic oil fuels that are coming into development, which are absolutely filthy. If those continue there is no way that we can maintain an operable atmosphere.

And don’t even get me going about clean coal. That’s the biggest example of double-speak that you have every heard. Show me the clean coal. Putting the word ‘clean’ in front of coal doesn’t make it clean. We’re nowhere near having any technology that would allow us to sequester that. So, we need to end coal. We need to end coal immediately. As soon as possible. It’s going to cause huge social dislocation and it’s going to be extremely difficult; it’s going to be a different kind of life. But it’s going to be life: there’s going to be continued life. Whereas if the world’s coal stocks are burned there will not be life.

We need to really both stabilize and then reduce human population. There’s a whole range of non-coercive measures that could be tried first. Massive education programs for women, widespread availability of birth control, as well as things like incentives for zero or one or two children where there’s tax benefits or preferential access to education. The planet was not meant to sustain 7 or 9 billion super-predators, each that want to consume at the level of an American. It’s a physical impossibility. So we need to be looking at revolutionary action, in terms of real abrupt sudden change, in those areas.

The population issues, as I mentioned, is really tied in heavily with consumption. It’s not just the population that matters, it’s the total consumption of a population, and so you get into equity issues of should there be people in the world who are worth more than nations, while there’s two billion people that make under two dollars a day, while there’s 800 million people that don’t have access to clean water? What sort of world is that?

As long as those huge economic disparities and consumption continue there’s nothing that can be done to protect the Earth.

Mongabay: You’ve been talking about a need for revolutionary change. To date, you’ve been very heavily involved on the internet and in policy, on using activism and protests—all sorts of different ways to create change. Would you call yourself a pacifist? Do you consider violence a means to no end? Or would you advocate violence to create this kind of change? Are you strictly saying that we need to walk the path of Gandhi or Martin Luther King Junior to create this kind of change?

Aerial view of the Tongass Forest, which is threatened by logging deals with the US government. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Glen Barry: Well, that’s a very good questions and it’s very complicated. I was in the military and actually ended up leaving as a conscientious objector. So I have been a pacifist. And I guess I’m a failed pacifist largely because I never could think of something I was willing to kill for: I wasn’t willing to kill for religion; I wasn’t willing to kill for my country; I guess if someone was knocking on my door and attacking my family, I would do something; but I really despise the industrial military complex which has developed.

Up until World War I after a war was done the troops demobilized and armies were essentially taken apart, now we have these huge standing expenditures that are just sapping the Earth.

Now, with that said, I have found something I am willing to fight for: I’m willing to fight for biological and ecological life on this planet, which I believe is on the verge of ending. I think, as an academic—I’m not trying to incite any sort of imminent violence, that’s very important—but I am trying to do is ask: are there revolutionary tactics and strategies that could be used to make the changes? And let’s discuss them; we can discuss geo-engineering, you know, putting mirrors above our planet, but we can’t discuss whether now might be a time for revolutionary change?

I’m an incredible admirer of both Gandhi and King and clearly we have to exhaust every non-violent means of trying to end these crises, which are going to cause such suffering. But I don’t think that the meaning of [Gandhi and King’s] success is that there is never a time that we will ever fight again. Those were unique historical circumstances: in India you had a long-running independence movement where there was time to get things done; you knew that eventually there was going to be independence, it was just a question of when. Similarly with the civil rights movement that had gone on for over a century.

This is a very very different situation—global ecosystem collapse—than we have ever faced before. We’ve tried non-violent protests for almost three decades. We’ve tried compromise. We’ve tried accommodation, and we haven’t gotten anywhere near the magnitude of social or political change that we need.

So, can we discuss blockading buildings? Can we discuss stopping coal plants from operating? Can we discuss an escalating series of actions that could be taken—it’s possible, it could happen, it might be necessary. Can we discuss that? And that’s what I’m trying to do is open political space for political-ecological scholarship and discussion and activism around these topics.

I firmly believe that on a personal level—without asking anyone to do anything illegal—that it may well come to a period where a cell-based structure that carried out sabotage and very carefully-conceived insurgency activity against the equipment and people destroying the Earth, may well be the one and only means that we have to stop what are such insurmountable trends destroying the Earth.

Mongabay: What gives you hope for the future?

Glen Barry: Ecology. The Internet. The merging of human rights and environmentalism. And the realization, together, what those three mean to us in terms of realizing that we’re all one people. We’re global citizens; we’re all in this together, and I believe that there is a movement growing that is committed to doing what has to be done to sustain Gaia.

Image courtesy of Ecological Internet. Copyrighted by New Scientist.

Editor’s note: Since the publication of this interview, Glen Barry has fabricated stories about Mongabay.com, misrepresented our views, and launched personal attacks against our staff.

Related articles

Timber certification is not enough to save rainforests

(06/02/2010) In the 1980s and 1990s pressure from activist groups led some of the world’s largest forestry products companies and retailers to join forces with environmentalists to form the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a certification standard that aims to reduce the environmental impact of wood and paper production on natural forests. Despite initial skepticism on whether buyers would pay a premium for greener forest products, FSC quickly grew and by 2000 had become a standard in many markets, including Europe and the United States. Companies like Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Ikea are today strong supporters of the FSC. But the FSC has not been without controversy. In recent years some activists have voiced concern about FSC standards as well as the credibility of auditors that certify timber operations. Among the initiative’s supporters is the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), a group best known for its aggressive protest tactics. RAN says engagement with the FSC is better than the alternative: leaving the timber industry to devise its own sustainability standards.

World failing on every environmental issue: an op-ed for Earth Day

(04/22/2010) The biodiversity crisis, the climate crisis, the deforestation crisis: we are living in an age when environmental issues have moved from regional problems to global ones. A generation or two before ours and one might speak of saving the beauty of Northern California; conserving a single species—say the white rhino—from extinction; or preserving an ecological region like the Amazon. That was a different age. Today we speak of preserving world biodiversity, of saving the ‘lungs of the planet’, of mitigating global climate change. No longer are humans over-reaching in just one region, but we are overreaching the whole planet, stretching ecological systems to a breaking point. While we are aware of the issues that threaten the well-being of life on this planet, including our own, how are we progressing on solutions?

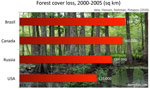

United States has higher percentage of forest loss than Brazil

(04/26/2010) Forests continue to decline worldwide, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS). Employing satellite imagery researchers found that over a million square kilometers of forest were lost around the world between 2000 and 2005. This represents a 3.1 percent loss of total forest as estimated from 2000. Yet the study reveals some surprises: including the fact that from 2000 to 2005 both the United States and Canada had higher percentages of forest loss than even Brazil.

Big compromise reached on Canada’s Boreal by environmental groups and forestry industry

(05/19/2010) In what is being heralded as the ‘world’s largest conservation agreement’ 20 Canadian forestry companies and nine environmental organizations have announced an agreement covering 72 million hectares of the Canadian boreal forest (an area bigger than France). Reaching a major compromise, the agreement essentially ends a long battle between several environmental groups and the companies signing on, all members of the Forest Products Association of Canada (FPAC).

![]()

(05/04/2010) Most people who are trying to change the world stick to one area, for example they might either work to preserve biodiversity in rainforests or do social justice with poor farmers. But Dr. Ivette Perfecto was never satisfied with having to choose between helping people or preserving nature. Professor of Ecology and Natural Resources at the University of Michigan and co-author of the recent book Nature’s Matrix: The Link between Agriculture, Conservation and Food Sovereignty, Perfecto has, as she says, “combined her passions” to understand how agriculture can benefit both farmers and biodiversity—if done right.

US emissions from coal could be stopped in 20 years

(05/03/2010) A new study in Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) concludes that the US could stop all emissions from coal-fired plants within 20 years time using only existing technologies and some that will be ready within the next decade. Such an accomplishment would go a long way toward lowering the US’s carbon emissions and mitigating the impact of climate change, according to the researchers.

(05/03/2010) Over the past 30 years billions of dollars has been committed to global conservation efforts, yet forests continue to fall, largely a consequence of economic drivers, including surging global demand for food and fuel. With consumption expected to far outstrip population growth due to rising affluence in developing countries, there would seem to be little hope of slowing tropical forest loss. But some observers see new reason for optimism—chiefly a new push to make forests more valuable as living entities than chopped down for the production of timber, animal feed, biofuels, and meat. While are innumerable reasons for protecting forests—including aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, and moral—most land use decisions boil down to economics. Therefore creating economic incentives to maintaining forests is key to saving them. Leading the effort to develop markets ecosystem services is Forest Trends, a Washington D.C.-based NGO that also organizes the Katoomba group, a forum that brings together a wide variety of forest stakeholders, including the private sector, local communities, indigenous people, policymakers, international development institutions, funders, conservationists, and activists.

(04/12/2010) 2010 marks a monumental milestone for the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) and its founder, Dr. Jane Goodall, DBE. Fifty years ago, Goodall, who is today a world-renowned global conservation leader, first set foot on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, in what is now Tanzania’s Gombe National Park. The chimpanzee behavioral research she pioneered at Gombe has produced a wealth of scientific discovery, and her vision has expanded into a global mission ‘to empower people to make a difference for all living things.’ Time, however, has not stood still for Gombe. The wild chimps of the area have suffered as the local human population has swelled. Gombe National Park is now a forest fragment, a 35-square-kilometer island of habitat isolated in a sea of subsistence farming. Because the problems facing Gombe—unsustainable land practices, overpopulation, and a cycle of poverty—are typical of many other areas, lessons learned by Dr. Goodall and her team provide valuable insights for solutions at Gombe and beyond.

What happened to China?: the nation’s environmental woes and its future

(04/01/2010) China has long been an example of what not to do to achieve environmentally sustainability. Ranking 133rd out of 146 countries in 2005 for environmental performance, China faces major environmental problems including severe air and water pollution, deforestation, water-issues, desertification, extinction, and overpopulation. A new article in Science discusses the complex issues that have led to China’s environmental woes, and where the nation can go to from here.

UN mulls global environment organization

(03/02/2010) Mass extinction, ocean acidification, deforestation, pollution, desertification, and climate change: the environmental issues facing the world are numerous and increasingly global in nature. To respond more effectively, the United Nations is considering forming a World Environmental Organization or WEO, similar to the World Trade Organization.

Will it be possible to feed nine billion people sustainably?

(01/28/2010) Sometime around 2050 researchers estimate that the global population will level-out at nine billion people, adding over two billion more people to the planet. Since, one billion of the world’s population (more than one in seven) are currently going hungry—the largest number in all of history—scientists are struggling with how, not only to feed those who are hungry today, but also the additional two billion that will soon grace our planet. In a new paper in Science researchers make recommendations on how the world may one day feed nine billion people—sustainably.

New report: world must change model of economic growth to avert environmental disaster

(01/25/2010) For decades industrialized nations have measured their success by the size of their annual GDP (Gross Domestic Product), i.e. economic growth. The current economic model calls for unending growth—as well as ever-rising consumerism—just to remain stable. However, a new report by the New Economics Foundation (nef) states that if countries continue down a path of unending growth, the world will be unable to tackle climate change and other environmental issues.

REDD may miss up to 80 percent of land use change emissions

(12/11/2009) The political definition of ‘forest’ used in REDD (Reduce Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) threatens to undermine the program’s objective to conserve ecosystems for their ability to sequester carbon, according to a new analysis by the Alternatives to Slash and Burn (ASB) Partnership for Tropical Forest Margins. In an analysis of three Indonesian provinces using REDD proposals for carbon accounting, ASB found that REDD may miss up to 80 percent of the actual emissions due to land use change. The carbon accounting problems could be fixed, according to ASB, by expanding REDD’s purpose from reducing emissions linked to deforestation (considering the problematic definition of forests) to reducing emission from all land use changes that either release or capture greenhouse gases, including but not limited to forests.