The fourth in an interview series with participants in the 5th Frugivore and Seed Dispersal International Symposium.

Scientists are just beginning to uncover the complex relationship between healthy biodiverse tropical forests and seed dispersers—species that spread seeds from a parent tree to other parts of the forest including birds, rodents, primates, and even elephants. By its very nature this relationship consists of an incredibly high number of variables: how abundant are seed dispersers, which animals spread seeds the furthest, what species spread which seeds, how are human impacts like hunting and deforestation impacting successful dispersal, as well as many others. Dr. Kimberly Holbrook has begun to answer some of these questions.

Performing her Master’s work in Cameroon, Holbrook explained to mongabay.com in an interview leading up to the 5th Frugivore and Seed Dispersal International Symposium, how she discovered that African forest hornbills may spread seeds much further than expected.

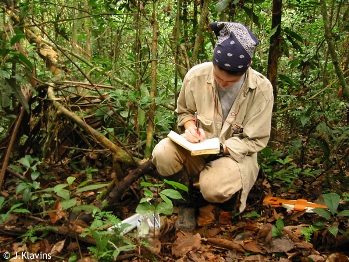

Kimberly Holbrook in field with C. atrata at Bouamir Research Station, Cameroon. Photo by: Kimberly Holbrook. |

“They have very large home ranges that varied between 925 hectares to more than 4,000 hectares. These home ranges are much larger than those reported for other African avian frugivores as well as all earlier estimates of African hornbill home ranges,” Holbrook says, adding that “these two species of forest hornbill engaged in landscape-scale movements travelling up to 290 kilometers over a two to three month period.”

These findings are important because they show that hornbills are capable of carrying seeds incredible distances—i.e. long-distance dispersal—from parent trees, aiding forest diversity by carrying species to new areas. Think of the hornbills as the boats which carried the Polynesians from one far-flung island to another: without birds or other long distance dispersers a tree species could become stuck in an ecosystem ‘island’.

“Long-distance dispersal is also fundamental to the spread and survival of plant populations and contributes to gene flow between populations,” explains Holbrook. “Another advantage is that long-distance dispersers enable plant offspring to sample larger areas creating the opportunity to escape host-specific pathogens and reduce kin competition. Finally, long-distance dispersers may facilitate arrival of rare species and colonization to gaps, thus helping contribute to forest regeneration.” Holbrook believes African hornbills may travel such distances in order to follow fruiting trees.

On the other side of the world, Holbrook studied how human impacts affect seed dispersers and, in turn, the entire forest, including our impact on long-distance dispersers.

“In Ecuador I studied fruit removal and effective dispersal (or recruitment) distances at two sites that differed in hunting pressure. In the site with high hunting pressure, I found that significantly fewer numbers of large frugivores were visiting fruiting trees and that overall fewer seeds were removed from trees based upon seed trap data,” Holbrook says.

Fruit of a neotropical nutmeg, Virola flexuosa. Photo courtesy of Kimberly Holbrook. |

She also found evidence that seeds traveled twice as far in the non-hunted sites, showing that intensive hunting targets the large fruit-eating species, such as big birds and primates, which are capable of carrying seeds the furthest.

“Seed dispersal is one of the many very important ecological processes that not only impact the ecology of forests and dispersers, but also the evolutionary relationships that exist there. For approximately 60-90 percent of tropical woody plant species, seed dispersal is a critical service essential for spread and survival,” Holbrook says.

Despite the complexities of seed dispersal ecology, the lesson is quite simple: without seed dispersers, and especially long-distance marathon dispersers, the structure of the forest will change forever.

In a May 2010 interview mongabay.com spoke with Kimberly Holbrook about the ecology of seed dispersal, the increasing importance of hornbills and toucans, the difficulties of estimating an economic value for seed dispersal, and how hunting and deforestation impact successful dispersal.

AN INTERVIEW WITH KIMBERLY HOLBROOK

Mongabay: What is your background?

Kimberly Holbrook collecting seedling data at Yasuní Research Station, Ecuador. Photo courtesy of Kimberly Holbrook. |

Kimberly Holbrook: I am an ecologist with primary interests in tropical forest diversity, plant-animal interactions, and conservation biology. My Master’s work was conducted in Cameroon where I studied the dispersal ecology of hornbills. The main findings from this research were that hornbills make long-distance movements travelling up to 290 km far outside the boundaries of the reserve where I worked. My PhD research focused on the impacts of hunting on seed dispersal in Ecuador. Comparing two sites that differed in hunting pressures I found significant decreases in dispersal services (e.g., visits to fruiting trees and fruit removal from parent trees) as well as significantly shorter dispersal distances at the hunted site.

Currently, I am working as a postdoctoral researcher in Spain investigating aspects related to the practical application of conservation, including the impacts of human activities on long-distance dispersal in plants and the population dynamics and spread of invasive species.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in rainforest ecology?

Kimberly Holbrook: I first became interested in tropical forest ecology when I traveled for a year in Southeast Asia, India, and China. My first view of a rainforest was while travelling by ship up the west coast of Sumatra. I was completely captivated by the apparent diversity and complexity of the forest. Upon finishing my undergraduate degree, I took a volunteer position working with hornbills in Cameroon where I had my first opportunity to learn about the importance of ecological relationships in tropical forests. Given my interests in birds, plants, and seed dispersal, it made perfect sense to pursue plant-animal interactions in the tropics.

Mongabay: Any advice for students interested in studying rainforests?

Kimberly Holbrook: My first bit of advice is to go to the rainforest!! Get a job—even if it is to volunteer—or take a tropical ecology field course so you can have an idea of what the environment is like. It will also give you a chance to start thinking about the kinds of questions you might develop as a student. I think that the best way to find out what kinds of organisms and ecological interactions are most interesting is through direct experience.

SEED DISPERSING

Mongabay: Why is seed dispersal such an important component of tropical forest ecology?

View from canopy tower, Tiputini Biodiversity Station, Ecuador. Photo by: Kimberly Holbrook. |

Kimberly Holbrook: Seed dispersal is one of the many very important ecological processes that not only impact the ecology of forests and dispersers, but also the evolutionary relationships that exist there. For approximately 60-90% of tropical woody plant species, seed dispersal is a critical service essential for spread and survival. For countless animal species, tropical tree fruits provide the necessary food and nutrition to survive and reproduce. Figs, for example, are especially important in providing food, often during non-fruiting seasons when other food sources are unavailable or much reduced. Other fruits such as those in the Myristicaceae (nutmegs) and Lauraceae (avocados) families provide high quality lipid-rich nutrition, crucial for many rainforest animals.

Mongabay: What is the ‘seed shadow’? How do you determine this for fruit-eating species like hornbills?

Kimberly Holbrook: The seed shadow is the spatial distribution or pattern of seeds that are dispersed from fruiting plants. Determining where in the landscape that the next generation will establish, the seed shadow can vary greatly depending on the dispersal mechanism that a particular plant species relies upon. Technically, a seed shadow is a representation of the dispersal pattern generated by all visiting frugivores. To determine a specific frugivore-generated seed shadow, as I have done with hornbills and toucans, you would need to collect data on animal movements and on seed retention times. Animal movement patterns are usually estimated using radio telemetry and seed retention can be calculated with captive feeding trials where regurgitation and/or defecation times are measured. These two types of data are then combined to tell us the probability of the frugivore dispersing a seed to a particular distance. The result is a two dimensional curve showing probability of seed deposition plotted against distance dispersed.

Mongabay: What makes hornbills and toucans such effective seed dispersers?

Black-casqued hornbill (Ceratogymna atrata) female captured in Cameroon. Photo by: T. Dietsch. |

Kimberly Holbrook: Effective dispersal is usually based on quantity and quality components that combine to increase plant fitness. From a quantitative perspective, highly frugivorous hornbills and toucans are effective because they typically make numerous visits and remove relatively high proportions of fruits per visit. From a qualitative perspective, these large frugivores treat seeds gently by swallowing them whole and later regurgitating or defecating the seeds intact. Another qualitative measure is whether seeds are dispersed to appropriate sites where the plant can survive and become an adult. Although this last component is more difficult to measure, because hornbills and toucans are able to move seeds long distances they likely increase the probability that a seed will reach a suitable germination site.

Mongabay: You are the first to measure the distance traveled by African hornbills. What were your results? Why is this data important to understanding seed dispersal?

Kimberly Holbrook: Our initial study on African forest hornbill (Ceratogymna and Bycanistes) movements showed two things. First, they have very large home ranges that varied between 925 ha to more than 4,000 ha. These home ranges are much larger than those reported for other African avian frugivores as well as all earlier estimates of African hornbill home ranges. The second finding was that these two species of forest hornbill engage in landscape-scale movements travelling up to 290 km over a two to three month period. Most of the observed movements corresponded with a decrease in hornbill abundances that correlated with low fruit availability, suggesting that hornbills track fruit resources.

Mongabay: Why are long-distance dispersers so important?

White-throated toucan (Ramphastos tucanus) female captured in Ecuador. Photo by: Kimberly Holbrook. |

Kimberly Holbrook: Long-distance dispersers are important because they allow plants to disperse their seeds to new and potentially more suitable germination sites. Long-distance dispersal is also fundamental to the spread and survival of plant populations and contributes to gene flow between populations. Another advantage is that long-distance dispersers enable plant offspring to sample larger areas creating the opportunity to escape host-specific pathogens and reduce kin competition. Finally, long-distance dispersers may facilitate arrival of rare species and colonization to gaps, thus helping contribute to forest regeneration.

Mongabay: Is there a way of putting an economic value on seed dispersal and seed dispersers like hornbills and toucans? Any estimates?

Kimberly Holbrook: That is a very good question. I have been thinking a lot about this since the value of ecosystem services have historically been overlooked by agencies that are responsible for protecting our environments. Certain services provided by ecosystems, such as clean air and water, have received most of the attention; however, pollination and seed dispersal are much less recognized. This is perhaps due the focus on human health and well-being, rather than ecosystem well-being. As far as I know there have not been any kinds of estimates of economic value on seed dispersal suggested in either temperate or tropical zones. So, I don’t have an answer, but I encourage that we think about how to value certain groups of organisms that provide such important services.

HUMAN IMPACT

Mongabay: In what ways are humans in general impacting seed dispersal in tropical forests in South America and Africa?

Badjue hunter with moustached guenons (Cercopithecus cephus) in Kompia, Cameroon. Photo by: Kimberly Holbrook. |

Kimberly Holbrook: Humans impact species interactions, such as seed dispersal, either indirectly though habitat alteration or directly through species removal (i.e., hunting). Habitat alteration is usually due to deforestation or fragmentation of forests through logging, clearing for living space and agriculture, ranching, and road building. When tropical forest habitats are fragmented or cleared, many of the larger seed disperser species (e.g. primates, guans, tapirs) disappear or decline in abundance, resulting in a decline in dispersal services. Long-distance dispersal may be disproportionately affected due to the higher sensitivity of large-bodied frugivores to habitat loss and hunting.

Mongabay: You recently studied the impact of hunting specifically on seed dispersal in Ecuador. What were your findings?

Kimberly Holbrook: In Ecuador I studied fruit removal and effective dispersal (or recruitment) distances at two sites that differed in hunting pressure. In the site with high hunting pressure, I found that significantly fewer numbers of large frugivores were visiting fruiting trees and that overall fewer seeds were removed from trees based upon seed trap data. Research using molecular markers to match adult female trees with their offspring seedlings indicated that seed dispersal distances were twice as long at the non-hunted site compared to the hunted site, suggesting that loss of large frugivores has an impact on longer effective dispersal distances.

Mongabay: Do you think there’s a need for special protections for important seed dispersers?

Roadside clearing in Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. Photo by: Kimberly Holbrook. |

I think it’s difficult and probably not realistic to provide special protections for specific seed dispersers. There would likely be difficulty (and disagreement) in determining which species should be designated as ‘important’ dispersers. Simple conservation of habitat and local community education would probably have better results.

Mongabay: Why are hornbills and toucans becoming even more important as seed dispersers?

Kimberly Holbrook: Larger-bodied frugivores, such as primates, are more sensitive to habitat fragmentation and more targeted by hunters than hornbills and toucans. Thus, hornbills and toucans may be able to replace or compensate for dispersal services as these other larger dispersers decline in numbers. However, ecological substitution is dependent on large dietary overlap between species, which does not always occur as shown by some African studies. It has also been suggested that in more heavily hunted forests, where dispersers are depleted, the likelihood of compensation is reduced.

Mongabay: How is forest fragmentation affecting successful seed dispersal?

Forest fragmentation can have varying effects on seed dispersal. Smaller-seeded plant species that attract a broad frugivore assemblage may experience successful dispersal. On the other hand, studies have shown that dispersal of large-seeded species in forest fragments is severely limited as their larger frugivores become locally extinct or severely reduced in numbers. There are, however, many other variables that affect successful seed dispersal (e.g., pollination limitation, seed predation, seedling recruitment requirements, and herbivory), which should be considered when evaluating dispersal success.

Mongabay: Having spent time in the tropics of South America and Africa, what are other threats to rainforests that concern you?

Field team on hornbill tracking project, Cameroon. Photo courtesy of Kimberly Holbrook. |

Kimberly Holbrook: On local and regional scales, timber extraction, clearing for agriculture and ranching, oil exploration, mining, bush meat hunting, and the introduction of exotic species are all major threats. At a larger landscape and/or global scale, fossil fuel consumption and associated climate change is another concern.

Mongabay: What research would you like to pursue in the future?

Kimberly Holbrook: I am interested in pursuing research that links biological diversity with healthy and functioning ecosystems. I think we need to better understand how the loss of biodiversity impacts important ecosystem services, such as seed dispersal and pollination. I would like to explore how scientists can partner with local communities, non-governmental organizations, and governments to both promote and protect biodiversity. We should support not only stronger environmental policies, but also involve ourselves in communicating the importance of biodiversity both locally and globally.

Black-casqued hornbill (Ceratogymna atrata) male captured in Cameroon. Photo by: B.D. Hardesty.

Related articles

How hornbills keep Asian rainforests healthy and diverse, an interview with Shumpei Kitamura

(04/26/2010) Hornbills are one of Asia’s most attractive birds. Large, colorful, and easier to spot than most other birds, hornbills have become iconic animals in the tropical forests of Asia. Yet, most people probably don’t realize just how important hornbills are to the tropical forests they inhabit: as fruit-eaters, hornbills play a key role in dispersing the seeds of tropical trees, thereby keeping forests healthy and diverse. Yet, according to tropical ecologist and hornbill-expert Shumpei Kitamura, these beautiful forest engineers are threatened by everything from forest loss to hunting to the pet trade.

Seed dispersal in the face of climate change, an interview with Arndt Hampe

(04/05/2010) Without seed dispersal plants could not survive. Seed dispersal, i.e. birds spreading seeds or wind carrying seeds, means the mechanism by which a seed is moved from its parent tree to a new area; if fortunate the seed will sprout in its new resting place, produce a plant which will eventually seed, and the process will begin anew. But in the face of vast human changes—including deforestation, urbanization, agriculture, and pasture lands, as well as the rising specter of climate change, researchers wonder how plants will survive, let alone thrive, in the future?

(03/07/2010) There are few areas of research in tropical biology more exciting and more important than seed dispersal. Seed dispersal—the process by which seeds are spread from parent trees to new sprouting ground—underpins the ecology of forests worldwide. In temperate forests, seeds are often spread by wind and water, though sometimes by animals such as squirrels and birds. But in the tropics the emphasis is far heavier on the latter, as Dr. Pierre-Michel Forget explains to mongabay.com. “[In rainforests] a majority of plants, trees, lianas, epiphytes, and herbs, are dispersed by fruit-eating animals. […] As seed size varies from tiny seeds less than one millimetres to several centimetres in length or diameter, then, a variety of animals is required to disperse such a continuum and variety of seed size, the smaller being transported by ants and dung beetles, the larger swallowed by cassowary, tapir and elephant, for instance.”

New study: why plants produce different sized seeds

(02/17/2010) The longstanding belief as to why some plants produce big seeds and others small seeds is that in this case bigger-is-better, since large seeds have a better chance of survival. However, Helene Muller-Landau, staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and head of the HSBC Climate Partnership’s effort to quantify carbon in tropical forests, grew dissatisfied with that explanation. For example, if big seeds were always the ‘right’ evolutionary path than why would any plants evolve small seeds? In a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Muller-Landau argues for a more complex explanation involving a trade-off between surviving stressful conditions and taking full advantage when the conditions are just right.

Loss in biodiversity may be killing bees

(01/20/2010) A decline in diverse plants species on which to feed may be causing a similar decline in bee survival, according to a new paper in Biology Letters.

Photos: park in Ecuador likely contains world’s highest biodiversity, but threatened by oil

(01/19/2010) In the midst of a seesaw political battle to save Yasuni National Park from oil developers, scientists have announced that this park in Ecuador houses more species than anywhere else in South America—and maybe the world. “Yasuní is at the center of a small zone where South America’s amphibians, birds, mammals, and vascular plants all reach maximum diversity,” Dr. Clinton Jenkins of the University of Maryland said in a press release. “We dubbed this area the ‘quadruple richness center.'”

How tree communities respond to distance to edges and canopy openness

(12/06/2009) Tropical forests frequently experience the opening and closing of canopy gaps as part of their natural dynamics. When an edge is created, and the area outside the boundary is a disturbed or unnatural system, forests can be seriously affected even at some distance from the fragmented edge, since sunlight and wind penetrate to a much greater extent. This increases tree mortality and, consequently, canopy openness close to the edge. Thus, canopy openness can be both part of a natural gap-dynamics cycle and the direct manifestation of human edge effects.

Forests recover faster from slash-and-burn when near intact forest reserves

(12/06/2009) Areas cleared for slash-and-burn agriculture recover faster when adjacent to a large block of untouched forest, but may take decades to regain a majority of their biodiversity after tree-felling, according to a new review of ecological studies, published in the December issue of Tropical Conservation Science, an open access journal.

Hunting across Southeast Asia weakens forests’ survival, An interview with Richard Corlett

(11/08/2009) A large flying fox eats a fruit ingesting its seeds. Flying over the tropical forests it eventually deposits the seeds at the base of another tree far from the first. One of these seeds takes root, sprouts, and in thirty years time a new tree waits for another flying fox to spread its speed. In the Southeast Asian tropics an astounding 80 percent of seeds are spread not by wind, but by animals: birds, bats, rodents, even elephants. But in a region where animals of all shapes and sizes are being wiped out by uncontrolled hunting and poaching—what will the forests of the future look like? This is the question that has long occupied Richard Corlett, professor of biological science at the National University of Singapore.

Birds found to be key protectors of forest in Tanzania

(07/02/2009) Seed-eating birds play a critical role in maintaining forests in the Serengeti by keeping seed-killing beetles in check, report researchers writing in the journal Science. The finding is another example of ecological interdependency between species.