An interview with Michael Jenkins, President and CEO of Forest Trends

|

|

Over the past 30 years billions of dollars has been committed to global conservation efforts, yet forests continue to fall, largely a consequence of economic drivers, including surging global demand for food and fuel. With consumption expected to far outstrip population growth due to rising affluence in developing countries, there would seem to be little hope of slowing tropical forest loss. But some observers see new reason for optimism—chiefly a new push to make forests more valuable as living entities than chopped down for the production of timber, animal feed, biofuels, and meat.

While are innumerable reasons for protecting forests—including aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, and moral—most land use decisions boil down to economics. Therefore creating economic incentives to maintaining forests is key to saving them.

|

Leading the effort to develop markets ecosystem services is Forest Trends, a Washington D.C.-based NGO that also organizes the Katoomba group, a forum that brings together a wide variety of forest stakeholders, including the private sector, local communities, indigenous people, policymakers, international development institutions, funders, conservationists, and activists. One of the programs of Forest Trends is operating three leading information portals on emerging ecosystem services markets, including Ecosystem Marketplace (ecosystemmarketplace.com), the Forest Carbon Portal (forestcarbonportal.com), and Species Banking (SpeciesBanking.com).

Michael Jenkins. |

Michael Jenkins is founder and president of Forests Trends. Jenkins started out as a tropical forester working in Haiti, Paraguay, Brazil, and other parts of Latin America in reforestation and agroforestry as means to sustainably boost rural livelihoods. But working in the field around the world, Jenkins saw that existing development and management models weren’t doing enough to keep forests standing.

After a decade with MacArthur Foundation, Jenkins founded Forest Trends in 1998 to “highlight the market value of natural ecosystems to promote their conservation”. In the process, Forest Trends and Katoomba have attracted a bright and innovative group of collaborators and partners who share the vision of using payments for ecosystem services as a platform for protecting forests and other ecosystems.

In 2010 Jenkins was recognized for his commitment to innovation in forest conservation with the Skoll Foundation’s Award for Social Entrepreneurship. Mongabay spoke with Jenkins about his work during the Skoll World Forum, held at Oxford University from April 14-16.

AN INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL JENKINS

Mongabay:

What is your background and what inspired you to start Forest Trends?

Michael Jenkins:

My background is that I am Tropical Forester, or should I say agroforester, by practice and training and I have worked in places like Paraguay, Haiti, and Brazil. And then after graduate work at Yale I kind of fell into a job at the Macarthur Foundation, where I worked for ten years and took the local experiences that I had in Haiti and in Paraguay and saw how these translated globally.

|

I got a unique global perspective from Macarthur, as well as a real exposure to lots of different types of institutions from all around the world, including the good, the bad and the ugly.

All of those experiences shaped the path that took me to Forest Trends. For example, in working with small farmers in rural Paraguay we tried to figure out how to make forest management more productive and more beneficial than the national cotton programs that didn’t make any sense at all and were really hurting them. Under the cotton program the small farmers and their 1 hectare, 2 hectare plots weren’t making any money and were over applying harmful pesticides. We looked for approaches that would make these farms more profitable, while engaging in products and crops that were going to be more sustainable. We started planting trees and raising bees.

When I was in Haiti it was kind of a similar thing, how to get trees on a landscape where the farmers are struggling to get any annual maize or millet crop at all. In that environment trees take five years if you’re lucky – ten years probably and the long-term logic was very hard to communicate to these small farmers. The program started with the standard package of local miracle trees—fast-growing and nitrogen fixing—yet we were surprised Haitians viewed them as weeds. So that led us to shift to planting native ‘useful’ species, as Haitians suggested, that would produce known and tangible products like valuable timber, fruit, or charcoal.

Forest in Lacassine National Wildlife Refuge, Louisiana (2010). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

So that was the path. It all was about this idea of making those tree and agroforestry systems more productive and more valuable in the short-term and longer term, that the farmer recognized.

My experience at MacArthur helped shape the institutional model of Forest Trends. After seeing so many organizations and efforts around the globe, completely disconnected or working at cross purposes, it was really clear to me that what the world did not need was another NGO with a big staff and its own separate vision. What we needed was what I like to call the “connective tissue” the connected all of the dots, all the organizations scattered around the globe. The connective tissue also needed to work from the very local up to the regional, national, and international level where global policy is negotiated. Local innovation needs to inform global policy, and you also need to make sure the local actors are informed about what is happening on a global scale, policies that will undoubtedly have an effect on them.

So that was part of the notion of a new type of organization. Also at MacArthur we started getting into a lot of unusual alliances, where we would bring in forest companies, financial institutions and businesses, as well as NGOs and communities, to try to figure out new ways to think about forest sustainability. Many times these groups had been enemies or at least perceived that way.

Deforestation in Mato Grosso, Brazil (2009). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

The design of Forest Trends operates on this idea that everybody has to be at the table when approaching an issue like creating a new environmental market. You need the producer, you need certifiers and registries, and other groups that represent the infrastructure a market needs; you need the governments that are going to create the legal framework and boundaries for these markets; you need the financial institutions that can help translate that value into a financial product; and you need the buyer ultimately buy the product. You need to frame the conversation so you can have all the stakeholders sitting around the table together. That is very hard—they speak really different languages, literally and figuratively—but I think it is the only way to truly succeed.

Mongabay:

Looking at the market issue, what is the landscape under the Copenhagen Accord?

Michael Jenkins:

Copenhagen was a huge disappointment to a lot of folks in the traditional market sense. It was a big disappointment for the carbon market and a lot of the big financial institutions, who have since backed away from the table. A lot of people in these institutions have been laid off and carbon desks have folded.

Rainforest of the Darien, Colombia (2010). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

But one interesting thing to come out of Copenhagen was that forestry became the “Promised Land”. It is especially ironic since three years ago forestry was in the same category as nuclear, you couldn’t trade it in the EU, ETS, the European Carbon trading system, effectively kept completely out of the climate negotiations. And now, coming out of Copenhagen, forests were one bright light that I think will translate into an agreement on forests at the next COP in Mexico this December.

We’ve since seen the commitment of bilateral donors—like Norway, Britain, Germany, France, Japan, and the U.S.—who have pledged around $4 billion since Copenhagen, just last December, for investment in forests and climate. This public finance will have to become the bridge between action today and sometime down the road when hopefully the climate process comes back together again including significant private sector involvement.

Mongabay:

So if you are a REDD developer in the midst of a project today, is there the potential to become part of an eventual market system?

Forest clearing in the Colombian Amazon (2010). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Michael Jenkins:

Yes. I think there is no question that we are in a period of growing investment in forests and climate. No question that that will happen. Whether it is going to be a UN multilateral deal that would look like a Kyoto Protocol kind of thing is the question – or whether it will be a set of different instruments that manifest as bilateral agreements between China and the US, or the State of California and states in Brazil. These ideas are on the table right now and being kicked around. But I think there is no question that there is going to be very significant new finance for forest and broader land-use activity like sustainable agriculture that can reduce carbon emissions. It’s kind of a creative time, so REDD developers should be looking at innovative ways of connection, with public financing, local community initiatives helping to build models of an eventual market system.

Mongabay:

There are lots of concerns with proposed forest carbon approaches, especially around transparency and equity for forest dependent-communities. What are some ways to address these?

Michael Jenkins:

One project that we have started to design with a number of local partners in Latin America and Africa is a tool to track public finance commitments for forests. Transparency and accountability are critical.

Forest river in the Colombian Chocó (2010). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

We’ve already developed the Forest Carbon Portal that currently tracks transactions. It allows users to see all the deals that are being done globally and includes a sort of a “nutritional label” – so you can compare projects and understand what is happening.

Our idea would be to track finance in the same way, so you can actually go on a map and see where money is going, for example Norway to Tanzania. You would be able to see what has happened, whether any communities are benefiting from it, what registries and accounting systems are in place to measure the impacts, and what is being monitored not only in terms of carbon emissions reductions, but also the other environmental and social benefits.

We see this real-time tracking system serving as a safeguard to make sure the money is used well and effectively and produces real climate benefits, real social benefits and real biodiversity benefits.

Mongabay:

What do you see as the best way to ensure that we have real safeguards and don’t just fall back into the traps of the old system? Institutions involved with REDD—like the World Bank—have a checkered history with maintaining safeguards and aren’t really trusted by many of the groups that will be most affected by REDD. Is there a role for activists to serve as watchdogs?

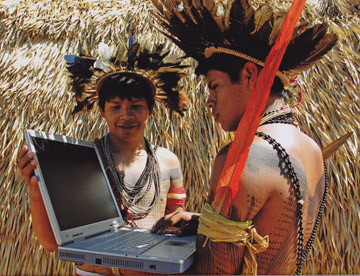

In Rondonia, Brazil, Surui use ACT-provided laptops to monitor their reserve using Google Earth technology. Photo © Fernando Bizerra Jr. |

Michael Jenkins:

Yes, definitely. Activists are an important and effective voice to bring attention to real issues and those local voices that many times are not heard. I also think there is another affirmative side to advocacy, which is then bringing these groups to the table to discuss and work through their concerns. People can either say, “Oh my God, here comes REDD!” and fear the day – or you can say, “Let’s make it the change we want it to be.”

Part of other work we do at Forest Trends, meant to complement this transparent information platform, is to actually work with projects on the ground, demonstrating how local communities can benefit from these emerging markets like REDD. For example, we have the project with Surui in the Brazil Amazon, which has established a legal precedent showing that forest communities have rights to the forest carbon in their territories. It is to demonstrate the process by which this finance can flow in a way so that a local indigenous community can benefit.

So I think there are two sides of advocacy work, a watchdog to keep everyone honest, and demonstration with partners to show how things could work.

Mongabay:

Do you see REDD as the stepping-stone towards valuing ecosystems for other services they provide humanity?

Michael Jenkins:

Actually, payments for other ecosystem services have been happening for years. We’ve been tracking about twenty different emerging environmental markets. There are public payment schemes for water, voluntary watershed protection schemes, water quality markets, wetland mitigation banks, conservation banks, and certified commodities like timber, coffee, and others. All of these tools are part of the universe of environmental markets.

Clearly carbon and REDD—the Carbon market before REDD and now REDD—have been the big “Kahuna” in terms of scale and attention but that might not always be the case.

For me the failure of Copenhagen was actually an opportunity to go back to a fundamental message, which is “there is no silver bullet here. Carbon is not going to save everybody.” If you look across the whole array of environmental markets, you might have a silver lining because, regardless of where you sit in the world, one of those markets is going to be relevant to you. And they will all hopefully be vehicles to invest in healthy and productive ecosystems, with real benefits to the stewards that deliver these public goods of clean water, stable climate, and biodiversity.

Mongabay:

Do you see environmental markets as a way to encourage corporations become better stewards of the environment?

Rainfall in the Pantanal, Brazil (2009). Photo by Rhett A. Butler  Rain falling over agricultural lands and forest in Mato Grosso, Brazil (2009). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Michael Jenkins:

Yes. But I think it happens in a series of stages. We have seen a lot of corporate social responsibility which I think is ‘environmental light’ for the most part. In some cases we are moving to a second stage that is a deeper commitment where businesses are recognizing investing in natural resources that are important to them, like Coca-Cola recognizing the fundamental need of clean water to produce their drink products. That step can be a significant challenge because many times these ecosystem services like water have historically been free.

But what is also interesting to think about is once you have put a price on that service—whether it’s pure water or nitrogen that pollutes water, whether it’s clean air or carbon emissions—then that becomes a price that is embedded in their business model. And so if an energy company is thinking about building a coal-fired power plant—and right now the price of that the clean air is free—it has no bearing on that decision. But once it becomes carbon at $28 a ton, that becomes a significant part of your decision in what kind of a facility you are going to build and where. The price signal becomes even a more systemic driver of company behavior change.

Mongabay:

We are already seeing pressure from companies on governments on some of these issues—do you think this will increase?

Michael Jenkins:

Yes, this is completely counterintuitive probably to most of us – but I feel like in the last decade our best partner in catalyzing these markets has been the private sector. Governments—certainly our government—haven’t shown much leadership up until recently. It has been some high minded businesses, alongside a few intrepid NGOs, that have been driving this shift.

Mongabay:

Would you say you are optimistic about the outlook for forests and other ecosystems?

Michael Jenkins:

I would say yes, I am optimistic. Having worked in forestry issues for some thirty years it seems like we finally have a really significant hook where we might able to turn the tide in terms of forests and really change the game. That has not been the case in the past.

Mongabay:

What do you see as the biggest remaining obstacles to realizing that future?

Michael Jenkins:

I think there is not one but a range of obstacles that interact together. We have got to get the policies in place. Markets and market-like instruments cannot work in isolation. Market tools are part of an ecosystem that requires regulation, information, and capacity to succeed. For these markets to reach scale and have strong drivers behind them we need to have a regulatory environment that sets the scene.

Deforestation in southern Laos (January 2009). Photos by Rhett A. Butler |

Copenhagen not succeeding meant that the potential for carbon markets as a whole suffered a significant setback. Investments around carbon have been drying up and the price of carbon has been going down.

So you need good policies in place that can serve the regulatory framework in which markets can function. You need the ‘architecture’ in place so that the buyer gets what he paid for and that the payment actually goes to the producer of that service. You need to make sure that these developing policies and markets include channels through which resources can flow to smallholders. We need to break that traditional model of markets screwing the poor.

That is the work that we all need to do; creating a new type of marketplace that invests in maintaining and restoring our natural infrastructure, our rural communities, and rewards innovation and collaborators at all levels. The historic opportunity of this moment is that we are the builders.

Mongabay:

Do you think there may be a forest agreement by the end of the year?

Michael Jenkins:

Yes, I do think there will be a Forestry Agreement. It would be a surprise if we didn’t get one. The Mexican Government is all ready to do this and the bilaterals are all ready for this, and NGO’s, business all want some positive step. And we are close.

Mongabay:

What would that look like? Would it be an international deal or would we see bilateral deals? Would there be financial incentives to stop deforestation?

Michael Jenkins:

Well, there again, that is the big question. My hope is that it would be a multilateral agreement of some sort. Whether it would be part of the UN-FCCC process or not is not clear; whether a forest agreement could drive that larger climate negotiation process is not clear.

Rain storm approaching over the Amazon River in Colombia (2010). Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

There will be more finance put on the table to work on slowing deforestation. The commitments that have been made already represent a significantly bigger investment in forest conservation than we have ever seen before.

Yet while there is a lot of excitement around the potential scale of the market carbon we need to balance that with other important opportunities for environmental markets out there that can help stop deforestation and invest in our natural resources. These are equally as valuable; maybe in the longer term, more valuable than the carbon market. Water markets, for example, are going to be more important than carbon markets over the long term because while the carbon market will eventually move us away from a carbon-based economy, but we can’t find a substitute for water. We are going to need ways or instruments to help us most efficiently and equitably manage our water resource in a time when we are going to be 9 billion people.

Mongabay:

Water will be a big issue for China. Is that going to be a way to engage it in environmental issues?

Michael Jenkins:

Water quality is probably the biggest environmental challenge facing China—they are definitely interested in ways to better manage that resource.

Oil palm plantation and logged-over forest in Borneo (April 2008). |

China and India, along with producer countries like Brazil, are fast becoming the central players in global consumption patterns. Simply we need to engage them as equal partners. When you think about the commodity roundtables that have formed around soy beans, palm oil, and sugar, we’re not just talking about influencing business in U.S. and Europe. The producer may well be in Brazil or Indonesia, while the prime consumers may be in China and India.

Mongabay:

But at present these roundtables are developing standards that are basically driven by Europe and the United States.

Michael Jenkins:

Yes. The roundtables have leading business corporations that are worried about their image in markets in Europe and US and the long-term sustainability of products. We need to engage Chinese and Indian corporations if we are to produce a stronger more systemic outcome.

Mongabay:

So the idea is you could engage China by establishing best practices for production or capture products that are manufactured in China but end up in Europe and the U.S.?

Michael Jenkins:

Right. You can take from experiences like forestry and certification. You get the corporate leaders from Europe to provide leadership adopting new, better standards and then China realizes that to sell into major markets they have to meet these standards.

Experience has been the export markets, and particularly those into Europe, are going to be the first adopters. And then hopefully it develops into an internal market with home grown standards and certifiers. That has been the case in Brazil with forestry and now we are seeing other early promising initiatives around soy and cattle.

For us that are focused on forests and ecosystem conservation, stabilizing this frontier between forests and agriculture using the mix of advocacy, standards, and market tools will be fundamental to stemming the tide of tropical deforestation.

Related articles

Ethnographic maps built using cutting-edge technology may help Amazon tribes win forest carbon payments

(11/29/2009) A new handbook lays out the methodology for cultural mapping, providing indigenous groups with a powerful tool for defending their land and culture, while enabling them to benefit from some 21st century advancements. Cultural mapping may also facilitate indigenous efforts to win recognition and compensation under a proposed scheme to mitigate climate change through forest conservation. The scheme—known as REDD for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation—will be a central topic of discussion at next month’s climate talks in Copenhagen, but concerns remain that it could fail to deliver benefits to forest dwellers.

Brazilian tribe owns carbon rights to Amazon rainforest land

(12/09/2009) A rainforest tribe fighting to save their territory from loggers owns the carbon-trading rights to their land, according to a legal opinion released today by Baker & McKenzie, one of the world’s largest law firms. The opinion, which was commissioned by Forest Trends, a Washington, D.C.-based forest conservation group, could boost the efforts of indigenous groups seeking compensation for preserving forest on their lands, effectively paving the way for large-scale indigenous-led conservation of the Amazon rainforest. Indigenous people control more than a quarter of the Brazilian Amazon.

(11/03/2009) Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD), a climate change mechanism proposed by the U.N., has been widely lauded for its potential to simultaneously deliver a variety of benefits at multiple scales. But serious questions remain, especially in regard to local communities. Will they benefit from REDD? While much lip-service is paid to community involvement in REDD projects, many developers approach local communities as an afterthought. Priorities lie in measuring the carbon sequestered in a forest area, lining up financing, and making marketing arrangements, rather than working out what local people — the ones who are often cutting down trees — actually need in order to keep forests standing. This sets the stage for conflict, which reduces the likelihood that a project will successfully reduce deforestation for the 15-30 year life of a forest carbon project. Brodie Ferguson, a Stanford University-trained anthropologist whose work has focused on forced displacement of rural communities in conflict regions in Colombia, understands this well. Ferguson is working to establish a REDD project in an unlikely place: Colombia’s Chocó, a region of diverse coastal ecosystems with some of the highest levels of endemism in the world that until just a few years ago was the domain of anti-government guerillas and right-wing death squads.

Are we on the brink of saving rainforests?

(07/22/2009) Until now saving rainforests seemed like an impossible mission. But the world is now warming to the idea that a proposed solution to help address climate change could offer a new way to unlock the value of forest without cutting it down.Deep in the Brazilian Amazon, members of the Surui tribe are developing a scheme that will reward them for protecting their rainforest home from encroachment by ranchers and illegal loggers. The project, initiated by the Surui themselves, will bring jobs as park guards and deliver health clinics, computers, and schools that will help youths retain traditional knowledge and cultural ties to the forest. Surprisingly, the states of California, Wisconsin and Illinois may finance the endeavor as part of their climate change mitigation programs.

Markets could save rainforests: an interview with Andrew Mitchell

(08/17/2008) Markets may soon value rainforests as living entities rather than for just the commodities produced when they are cut down, said a tropical forest researcher speaking in June at a conservation biology conference in the South American country of Suriname. Andrew Mitchell, founder and director of the London-based Global Canopy Program (GCP), said he is encouraged by signs that investors are beginning to look at the value of services afforded by healthy forests.

(04/02/2008) Last week London-based Canopy Capital, a private equity firm, announced a historic deal to preserve the rainforest of Iwokrama, a 371,000-hectare reserve in the South American country of Guyana. In exchange for funding a “significant” part of Iwokrama’s $1.2 million research and conservation program on an ongoing basis, Canopy Capital secured the right to develop value for environmental services provided by the reserve. Essentially the financial firm has bet that the services generated by a living rainforest — including rainfall generation, climate regulation, biodiversity maintenance and carbon storage — will eventually be valuable in international markets. Hylton Murray-Philipson, director of Canopy Capital, says the agreement — which returns 80 percent of the proceeds to the people of Guyana — could set the stage for an era where forest conservation is driven by the pursuit of profit rather than overt altruistic concerns.